Abstract

Aims: Elevated lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] is an overlooked and underdiagnosed risk factor for peripheral artery disease (PAD). Negligible testing rates of Lp(a) in patients with PAD are suspected to be largely caused by implementation barriers and poor awareness. Here, we report pilot results of the newly initiated Lp(a)-PAD inpatient care pathway that employs the LILAC-for-Lp(a) framework.

Methods: A review of the process of implementation of the inpatient Lp(a)-PAD pathway was undertaken using quality improvement methods. The prevalence of elevated Lp(a), and its association with the severity of chronic limb ischaemia were investigated.

Results: At 3 months after integrating detection of Lp(a) in the care of patients admitted to hospital for PAD-related limb ischaemia issues, 22.6% of the 106 patients were detected to have elevated Lp(a) levels ≥ 120 nmol/L, and 34.9% with mildly raised Lp(a) ≥ 70 nmol/L. There was a higher proportion of patients with levels ≥ 120 nmol/L compared with Lp(a) < 120 nmol/L who had category 6 classification of chronic limb ischaemia by Rutherford classification (95.8% vs 70.7%, p-value = 0.011). Lp(a) ≥ 120 nmol/L and Lp(a) as a continuous variable were associated with the highest severity of limb ischaemia, p = 0.032 and p = 0.045, respectively. The low-density lipoprotein (LDL) attainment goal in our patients with PAD was suboptimal; LDL-C < 1.4 mmol/L goal attainment was achieved in 30.2% of all patients and 25.0% of the group of elevated Lp(a), respectively.

Conclusion: This pilot study suggests that the LILAC-for-Lp(a) framework, via multidisciplinary collaboration and quality improvement methods, is helpful to integrate Lp(a) testing into PAD management.

Keywords

1. Introduction

Elevated lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] is a hypercholesterolaemia form that is frequently overlooked risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, including peripheral artery disease (PAD), despite calls for implementation of Lp(a), including in the recent Brussels international declaration document[1-9]. Studies show that higher Lp(a) blood levels are an independent risk factor associated with an increased risk of PAD onset, progression, and restenosis, worse major limb adverse outcomes, and increased rates of

Recent studies have shown that Lp(a) testing rates are very low in specialties managing patients with PAD, worse than cardiology[4,16]. Similarly, we noticed negligible testing rates locally for elevated Lp(a) in patients with PAD[17]. As shown by our recent educational efforts across various disciplines, the LILAC-for-Lp(a) concept was very well received and improved short-term confidence and perception of Lp(a) testing among healthcare professionals[10]. The LILAC cognitive aid-tool and framework serve to aid healthcare professionals to manage patients with elevated Lp(a)[1]; the first L denotes the role of Lp(a) as a cardiovascular risk factor. I and second L denote mitigation strategies to improve mitigatable risk factors, low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and Lp(a) levels. A is used as a reminder to Assessment, Atherosclerosis, and Aortic valve stenosis, and lastly, C denotes cascade testing for family members of individuals with severely elevated Lp(a)[18,19].

Here, we aimed to report our experience with a newly initiated Lp(a)-PAD care inpatient pathway that employs the LILAC-for-Lp(a) framework, at the 3 month time point. We also report the prevalence of elevated Lp(a) and its association with the severity of lower limb ischaemia in hospitalised patients with acute lower limb issues related to PAD.

2. Methods

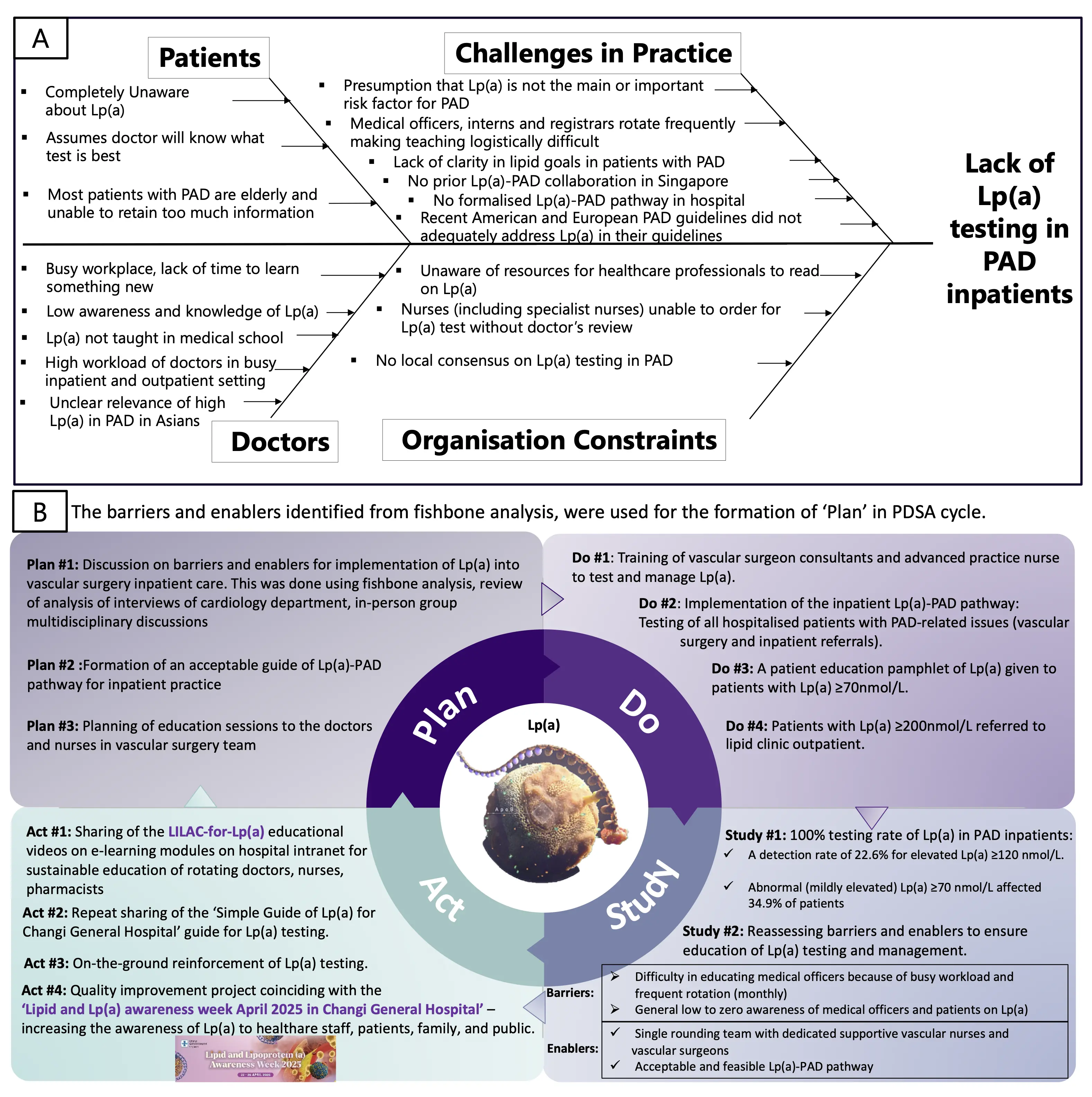

To construct a structured plan of testing and management of elevated Lp(a) detected in patients with PAD, three discussions were held over a few months between the lipid and endocrinology specialist (WJL) and the vascular team, which included vascular surgeons, an advanced practice nurse in vascular surgery, and a senior medical officer. Insights were also sought from our recent pre-implementation qualitative study involving 41 cardiology healthcare professionals[17]. The qualitative study revealed that major barriers to under-detection of elevated Lp(a) in hospital were the lack of a dedicated care pathway for testing and managing Lp(a), poor awareness and wide knowledge gaps among healthcare professionals, patients and the public. A fishbone analysis was undertaken to summarise the key barriers of testing of Lp(a) in vascular surgery discipline, followed by the formation of

A novel inpatient Lp(a)-PAD pathway using the LILAC-for-Lp(a) framework was executed on 26th February 2025 at Changi General Hospital. The aim was to improve inpatient detection and management of patients with elevated Lp(a) and PAD. The two key barriers given priority were the formation of a workflow for a busy inpatient practice and the launch of a sustainable education method in a hospital setting where medical officers and interns rotate monthly. Patients with mildly elevated Lp(a) levels ≥ 70 nmol/L were counselled to better manage cardiovascular risk factors and provided with a leaflet to read. Patients with severely elevated Lp(a) levels ≥ 200 nmol/L were referred to outpatient Lipid Clinic, where they were further managed using the LILAC-for-Lp(a) framework (Figure S1)[22].

Serum Lp(a) were measured with Tina-quant Lipoprotein(a) Gen.2 (Latex) Roche, with an inter-assay coefficient of variation ≤ 2.2%[22]. A threshold of 120 nmol/L was used, as our previous reports showed increased risk of coronary artery disease at this level[19]. To investigate the association of elevated Lp(a) ≥ 120 nmol/L with chronic lower limb ischaemia, logistic regression adjusted for age, body mass index (BMI), sex and chronic kidney disease was undertaken, comparing Lp(a) ≥ 120 nmol/L with Lp(a) < 120 nmol/L using the Rutherford classification for chronic limb ischaemia. Lp(a) was natural-log transformed for analysis as a continuous variable.

3. Results

Figure 1 shows a fishbone analysis summarising the key barriers to testing of Lp(a) in the vascular surgery discipline. Four key themes were identified: patients, doctors, challenges in practice and organisational constraints. A key barrier was the lack of a dedicated workflow for management of elevated Lp(a) in patients with PAD. Other key barriers included poor awareness of patients and doctors, frequent rotation of non-consultant doctors (i.e interns, medical officers and registrars), and that all nurses, including dedicated vascular nurses, were not allowed to order blood tests. The unclear local prevalence of elevated Lp(a) among patients with PAD also fuelled uncertainty about the value of testing of Lp(a) in patients with PAD. A one-page Lp(a) pathway was disseminated to doctors in the vascular and general surgery departments and made available on our hospital intranet (Figure S1).

Figure 1. Fishbone analysis (A) and first PDSA (B) cycle of a pilot implementation study of Lp(a) testing in hospitalized patients with PAD. PDSA: Plan-Do-Study-Act; PAD: peripheral artery disease.

At 3 months after the Lp(a)-PAD pathway was launched, 106 patients were hospitalised for PAD-related limb ischaemia issues. All were tested for Lp(a); 69.8% were male and mean age of 69 years (Table 1). Comorbidities were common: 99.1% had hypertension, 97.2% had hypercholesterolemia, 94.3% had diabetes, 45.3% had ischaemic heart disease, 18.9% had stroke and 37.7% had chronic kidney disease. The median Lp(a) was 38 nmol/L (range < 7 to 372 nmol/L). The detection rate for elevated Lp(a) levels ≥ 120 nmol/L was 22.6% and mildly raised Lp(a) ≥ 70 nmol/L was 34.9%. In this study, 95.8% in patients with elevated Lp(a) levels ≥ 120 nmol/L had the most severe category (category 6) of chronic limb ischaemia by Rutherford classification, a higher rate than the 70.7% of patients with

| All Patients (n = 106) | Lp(a) < 120 nmol/L (n =82) | Lp(a) ≥ 120 nmol/L (n = 24) | p-value | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 69.2 ± 10.0 | 69.1 ± 9.9 | 69.6 ± 10.7 | ns |

| Male (%) | 74 (69.8) | 32 (39.0) | 13 (54.2) | 0.058 |

| Statin prescribed (%) | 115 (99.1) | 81 (98.8) | 24 (100) | ns |

| Past Medical History | ||||

| Hypertension (%) | 105 (99.1) | 81 (98.8) | 24 (100) | ns |

| Diabetes (%) | 100 (94.3) | 77 (93.9) | 23 (95.8) | ns |

| Ischaemic heart disease (%) | 48 (45.3) | 39 (47.6) | 9 (37.5) | ns |

| CABG (%) | 11 (10.4) | 10 (12.2) | 1 (4.2) | ns |

| PCI (%) | 11 (10.4) | 10 (12.2) | 1 (4.2) | ns |

| Stroke (%) | 20 (18.9) | 13 (15.9) | 7 (29.2) | ns |

| Chronic kidney disease (%) | 40 (37.7) | 34 (41.5) | 6 (25.0) | ns |

| Dialysis (%) | 22 (20.8) | 19 (23.2) | 3 (12.5) | ns |

| Limb Events | ||||

| Angioplasty (%) | 87 (82.1) | 57 (82.6) | 18 (75.0) | ns |

| Amputation (%) | 71 (67.0) | 54 (65.9) | 17 (70.8) | ns |

| Toe amputation (%) | 54 (50.9) | 43 (52.4) | 11 (45.8) | ns |

| Below knee amputation (%) | 5 (4.7) | 5 (6.1) | 0 (0.0) | ns |

| Above knee amputation (%) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| Forefoot amputation (%) | 11 (10.4) | 5 (6.1) | 6 (25.0) | 0.016 |

| Mid-foot amputation (%) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| Rutherford Classification | ||||

| Grade 1 (%) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | ns |

| Grade IIA (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ns |

| Grade IIB (%) | 3 (2.8) | 2 (2.4) | 1 (0.0) | ns |

| Grade 3 (%) | 5 (4.7) | 5 (7.2) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| Grade 4 (%) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| Grade 5 (%) | 15 (14.2) | 15 (18.3) | 0 (0.0) | - |

| Grade 6 (%) | 81 (76.4) | 58 (70.7) | 23 (95.8) | 0.011 |

| Blood lipid concentrations | ||||

| Lp(a) level (median, IQR) | 38 (20, 110) | 28.5 (17, 49) | 178 (136, 225) | - |

| LDL-C level (median, IQR) | 1.7 (1.2, 2.4) | 1.7 (1.2, 2.5) | 1.8 (1.4, 2.3) | ns |

| LDL-C < 1.0 mmol/L (%) | 15 (14.2) | 12 (14.6) | 3 (12.5) | ns |

| LDL-C < 1.4 mmol/L (%) | 32 (30.2) | 26 (31.7) | 6 (25.0) | ns |

| LDL-C < 1.8 mmol/L (%) | 52 (49.1) | 42 (51.2) | 10 (41.7) | ns |

Lp(a): Lipoprotein(a); LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels; CABG: Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting; PCI: Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. ns: not significant; IQR: interquartile range; PAD: peripheral artery disease.

Enablers of this successful pilot implementation included the active collaboration of the vascular and lipid teams and adoption of an acceptable and feasible workflow. Another key enabler was that the existing inpatient vascular care was conducted by a single dedicated rounding team consisting of three vascular surgeons, a registrar, medical officers, and crucially, a dedicated inpatient advanced practice nurse clinician. To promote sustainability, strategies being employed are tutorials, e-learning, and exploration of nurse-led and pharmacist-led interventions.

4. Discussion

Here, we report that Lp(a) ≥ 70 nmol/L and ≥ 120 nmol/L affected 34.9% and 22.6% of patients with PAD admitted to hospital, respectively, highlighting an urgent unmet need. Our study found that elevated Lp(a) ≥ 120 nmol/L was associated with an increased risk of the most severe category of chronic limb ischaemia by Rutherford classification. As far as we are aware, there are no previously published reports of Lp(a) with Rutherford classification. This pilot implementation of the Lp(a)-PAD care pathway using LILAC revealed encouragingly positive results. The quality improvement analysis suggested a few important enablers[20,21]. These included an acceptable and simple Lp(a) workflow that used the LILAC-for-Lp(a) framework, which was approved by stakeholders. Additionally, a dedicated vascular nurse and a collaborative vascular team were crucial to promoting and sustaining the practice of Lp(a) testing and counselling. A continuous education strategy via short educational videos instead of long lectures was helpful for rotating doctors in a busy workplace.

An Australian study of 1,472 patients with PAD also revealed that Lp(a) ≥ 30 mg/dL (≈ 70 nmol/L) was associated with an increased hazard ratio of 1.2-1.3 times for PAD operations and peripheral revascularisation[12]. A systematic review of 15 studies showed that higher Lp(a) levels was associated with an increased risk of incident PAD events, re-stenosis, limb amputation and hospitalisation[10]. A recent meta-analysis of 51 studies reported that higher Lp(a) was associated with a 2.5-fold increased risk of PAD and coronary artery disease[14]. A study of Asian patients (including Singaporean) showed 3 times increased likelihood of requiring intervention and worse postoperative outcomes compared with Caucasians, suggesting Asians may be at greater risk[23].The pro-atherogenic,

The LILAC framework focuses on the importance of overall cardiovascular risk mitigation by controlling modifiable cardiovascular risk factors, while the results of cardiovascular outcome trials of specific Lp(a) lowering therapies are awaited. In our study, we found that 70% of patients did not achieve the LDL-C goal of < 1.4 mmol/L despite having active PAD issues, highlighting a large treatment gap. Similarly, a study in a German hospital found that only 16% of 263 patients with PAD had LDL-C < 1.4 mmol/L, which improved to 49%[12]. Despite calls by expert consensus and medical societies to recognise that elevated Lp(a) is an actionable risk factor, the implementation of Lp(a) remains a major challenge worldwide, with inertia in adoption even among medical specialists[2,3,5,18,24]. However, the 2024 American clinical guideline for PAD published jointly by ACC/AHA and other societies did not address Lp(a) at all[25], while the 2025 ESC guidelines for the management of PAD included only a single sentence recommending Lp(a) testing[5]. Therefore, harmonisation of recommendations across specialties related to PAD is necessary to facilitate implementation[1-3,25].

Limitations of this study include the small sample size, as only inpatients were included with no follow-up data. Nevertheless, we showed a feasible opportunistic strategy for detecting elevated Lp(a) of patients with PAD. Our approach may not be generalisable to other hospitals with different operational workflows. Chronic kidney disease affected 37.7% of our patients[23]; blood Lp(a) concentrations may be elevated due to renal impairment[26].

5. Conclusion

From this pilot study, we report that inpatient Lp(a) testing for patients with active PAD issues can be implemented via multidisciplinary collaboration between the lipid clinic, vascular team and nursing. Our study supports the need for systematic testing of patients with PAD.

Supplementary materials

The supplementary material for this article is available at: Supplementary materials.

Authors contribution

Loh WJ: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing-original draft.

Ho CJY: Formal analysis, writing-original draft.

Cheng SH, Lee PS, Lee SQ: Investigation, validation.

Ho DC: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, validation.

All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript and contributed to writing-review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

Wann Jia Loh reports receiving honoraria from Abbott, DKSH, Roche, Medtronic, Novartis, Inova, Kowa, and Amgen. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Ethical board review was not required according to institutional guidelines for this quality improvement and implementation project.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

None.

References

-

1. Kronenberg F, Mora S, Stroes ESG, Ference BA, Arsenault BJ, Berglund L, et al. Lipoprotein(a) in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and aortic stenosis: A European Atherosclerosis Society consensus statement. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(39):3925-3946.[DOI]

-

2. Kronenberg F, Bedlington N, Ademi Z, Geantă M, Silberzahn T, Rijken M, et al. The Brussels international declaration on lipoprotein (a) testing and management. Atherosclerosis. 2025;406:119218.[DOI]

-

3. Loh WJ, Watts GF. Detection strategies for elevated lipoprotein(a): Will implementation let the genie out of the bottle? Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2022;30(2):94-102.[DOI]

-

4. Bhatia HS, Hurst S, Desai P, Zhu W, Yeang C. Lipoprotein (a) testing trends in a large academic health system in the United States. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023;12(18):e031255.[DOI]

-

5. Mazzolai L, Teixido-Tura G, Lanzi S, Boc V, Bossone E, Brodmann M, et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of peripheral arterial and aortic diseases: Developed by the task force on the management of peripheral arterial and aortic diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Endorsed by the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Reference Network on Rare Multisystemic Vascular Diseases (VASCERN), and the European Society of Vascular Medicine (ESVM). Eur Heart J. 2024;45(36):3538-3700.[DOI]

-

6. Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, Koskinas KC, Casula M, Badimon L, et al. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk: The Task Force for the management of dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS). Eur Heart J. 2020;41(1):111-188.[DOI]

-

7. Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, Beam C, Birtcher KK, Blumenthal RS, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;139(25):e1082-e1143.[DOI]

-

8. Pearson GJ, Thanassoulis G, Anderson TJ, Barry AR, Couture P, Dayan N, et al. 2021 Canadian Cardiovascular Society guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults. Can J Cardiol. 2021;37(8):1129-1150.[DOI]

-

9. Koschinsky ML, Bajaj A, Boffa MB, Dixon DL, Ferdinand KC, Gidding SS, et al. A focused update to the 2019 NLA scientific statement on use of lipoprotein(a) in clinical practice. J Clin Lipidol. 2024;18(3):e308-e319.[DOI]

-

10. Masson W, Lobo M, Barbagelata L, Molinero G, Bluro I, Nogueira JP. Elevated lipoprotein (a) levels and risk of peripheral artery disease outcomes: A systematic review. Vasc Med. 2022;27(4):385-391.[DOI]

-

11. Thomas PE, Vedel-Krogh S, Nielsen SF, Nordestgaard BG, Kamstrup PR. Lipoprotein (a) and risks of peripheral artery disease, abdominal aortic aneurysm, and major adverse limb events. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;82(24):2265-2276.[DOI]

-

12. Golledge J, Rowbotham S, Velu R, Quigley F, Jenkins J, Bourke M, et al. Association of serum lipoprotein (a) with the requirement for a peripheral artery operation and the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events in people with peripheral artery disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(6):e015355.[DOI]

-

13. Koschinsky ML, Boffa MB. Lp(a) as a risk factor for peripheral artery disease: Context is everything. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2025;45(9):1505-1515.[DOI]

-

14. Tian X, Zhang N, Tse G, Li G, Sun Y, Liu T. Association between lipoprotein(a) and premature atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J Open. 2024;4(3):oeae031.[DOI]

-

15. Guédon AF, De Freminville JB, Mirault T, Mohamedi N, Rance B, Fournier N, et al. Association of lipoprotein (a) levels with incidence of major adverse limb events. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(12):e2245720.[DOI]

-

16. Eidensohn Y, Bhatla A, Ding J, Blumenthal RS, Martin SS, Marvel FA. Testing practices and clinical management of lipoprotein(a) levels: A 5-year retrospective analysis from the Johns Hopkins Hospital. Am J Prev Cardiol. 2024;19:100686.[DOI]

-

17. Wong AJ, Lum E, Loh WJ. Implementation of a lipoprotein(a) guide and pathway to detect elevated Lp(a) in patients at high risk for cardiovascular events. Atherosclerosis. 2025;407:119830.[DOI]

-

18. Loh WJ, Watts GF, Lum E. A short educational video for improving awareness and confidence of healthcare professionals in managing lipoprotein(a): A pilot study based on LILAC-for-Lp(a). Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2025;24(5):796-799.[DOI]

-

19. Loh WJ, Chan DC, Mata P, Watts GF. Familial hypercholesterolemia and elevated lipoprotein (a): cascade testing and other implications for contextual models of care. Front Genet. 2022;13:905941.[DOI]

-

20. Bechtold ML, Matteson‐Kome ML. Implementation science using the Plan‐Do‐Study‐Act (PDSA) cycle: Addressing hospital malnutrition with the global malnutrition composite score. Nutr Clin Pract. 2025;40(6):1369-1378.[DOI]

-

21. Harel Z, Silver SA, McQuillan RF, Weizman AV, Thomas A, Chertow GM, et al. How to diagnose solutions to a quality of care problem. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(5):901-907.[DOI]

-

22. Loh WJ, Koh XH, Yeo C, Ruan X, Chai SC, Chow W, et al. Lipoprotein(a) as a predictor of mortality in hospitalised patients with ischaemic heart disease. Front Endocrinol. 2025;16:1541712.[DOI]

-

23. Chen P, Patel PB, Ding J, Krimbill J, Siracuse JJ, O'Donnell TFX, et al. Asian race is associated with peripheral arterial disease severity and postoperative outcomes. J Vasc Surg. 2023;78(1):175-183.[DOI]

-

24. Loh WJ, Pang J, Simon O, Chan DC, Watts GF. Deficient perceptions and practices concerning elevated lipoprotein(a) among specialists in Singapore. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2025;12:1527351.[DOI]

-

25. Gornik HL, Aronow HD, Goodney PP, Arya S, Brewster LP, Byrd L, et al. 2024 ACC/AHA/AACVPR/APMA/ABC/SCAI/SVM/SVN/SVS/SIR/VESS guideline for the management of lower extremity peripheral artery disease: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2024;149(24):e1313-e1410.[DOI]

-

26. Hopewell JC, Haynes R, Baigent C. The role of lipoprotein (a) in chronic kidney disease. J Lipid Res. 2018;59(4):577-585.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite