Chengliang Zhao, School of Physical Science and Technology, Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Frontier Material Physics and Devices & Suzhou Key Laboratory of Intelligent Photoelectric Perception, Soochow University, Suzhou 215006, Jiangsu, China. E-mail: zhaochengliang@suda.edu.cn

Abstract

Optical vortices, characterized by their central singularities and spiral phase wavefront, have gained widespread attention in light manipulation and diverse applications. With their topological order being extended from integer to fraction, more unique properties have sprung out, such as continuous topological charges, fractional spiral-phase, expanded orbital angular momentum spectrum, and slit openings. These features have facilitated applications in areas such as optical tweezers, direction-selective edge enhancement imaging, robust rotational Doppler metrology, free-space communication, displacement sensing, and high-dimensional quantum entanglement. In recent years, advances in metasurface-based optical control, spatiotemporal pulse shaping, holographic imaging, and deep learning have spurred rapid innovation in the modeling, generation, and measurement of fractional vortex beams. This review begins with the fundamental theory of fractional vortex beams and surveys the latest developments in this rapidly evolving field. The scope of research has also expanded beyond optical vortices to include acoustic vortices. The growing interest in fractional vortex beams, coupled with ongoing technological innovations, is expected to pave the way for further advancements in this promising area of research.

Keywords

1. Introduction

Vortices are ubiquitous natural phenomena, spanning diverse fields such as fluid dynamics, light waves, quantum systems, acoustics, and astrophysics[1-5]. The study of optical vortices can be traced back to the theoretical work by Coullet et al. in 1989, who predicted—within the framework of a Maxwell–Bloch model—that laser cavities with a large Fresnel number could support states analogous to superfluid vortices[6]. In 1992, Allen et al. demonstrated that a Laguerre-Gaussian laser mode has a well-defined orbital angular momentum (OAM) equal to lħ per photon, where l is the topological charge (TC) and ħ is the reduced Planck constant[7]. This revealed the connection between macroscopic and quantum optics. Laguerre-Gaussian modes with integer OAM values constitute orthonormal solutions of the paraxial wave equation[8], laying the foundation for widespread applications of vortex beams in optical communications, quantum entanglement, holographic imaging, and more[1].

In 1994, Beijersbergen et al. generated fractional Laguerre–Gaussian modes using a spiral phase plate and observed that phase singularities with half-integer TCs appear displaced from the beam center[9]. Over the following three decades, various theoretical models of fractional vortex beams have been proposed, including Gaussian fractional vortex beam[10,11], fractional Laguerre-Gaussian beam[9,12], fractional Bessel beam[13], perfect fractional vortex beam[14], multi-opening fractional vortex beam[15], grafted fractional vortex beam[16], spiral fractional vortex beam[17], and fractional vortex arrays[18]. These beams exhibit distinctive properties such as continuous TCs, fractional spiral phase profiles, broadened OAM spectra[19-21], and slit openings[22-24], making them uniquely suitable for optical tweezers[15,18,25-31], directional edge-enhancement imaging[11,32-43], robust rotational Doppler metrology[21,44-46], free-space acoustic communication[47-61], ultra-dense encoding holography[17,62,63], displacement sensing[64,65], and high-dimensional quantum entanglement[66,67].

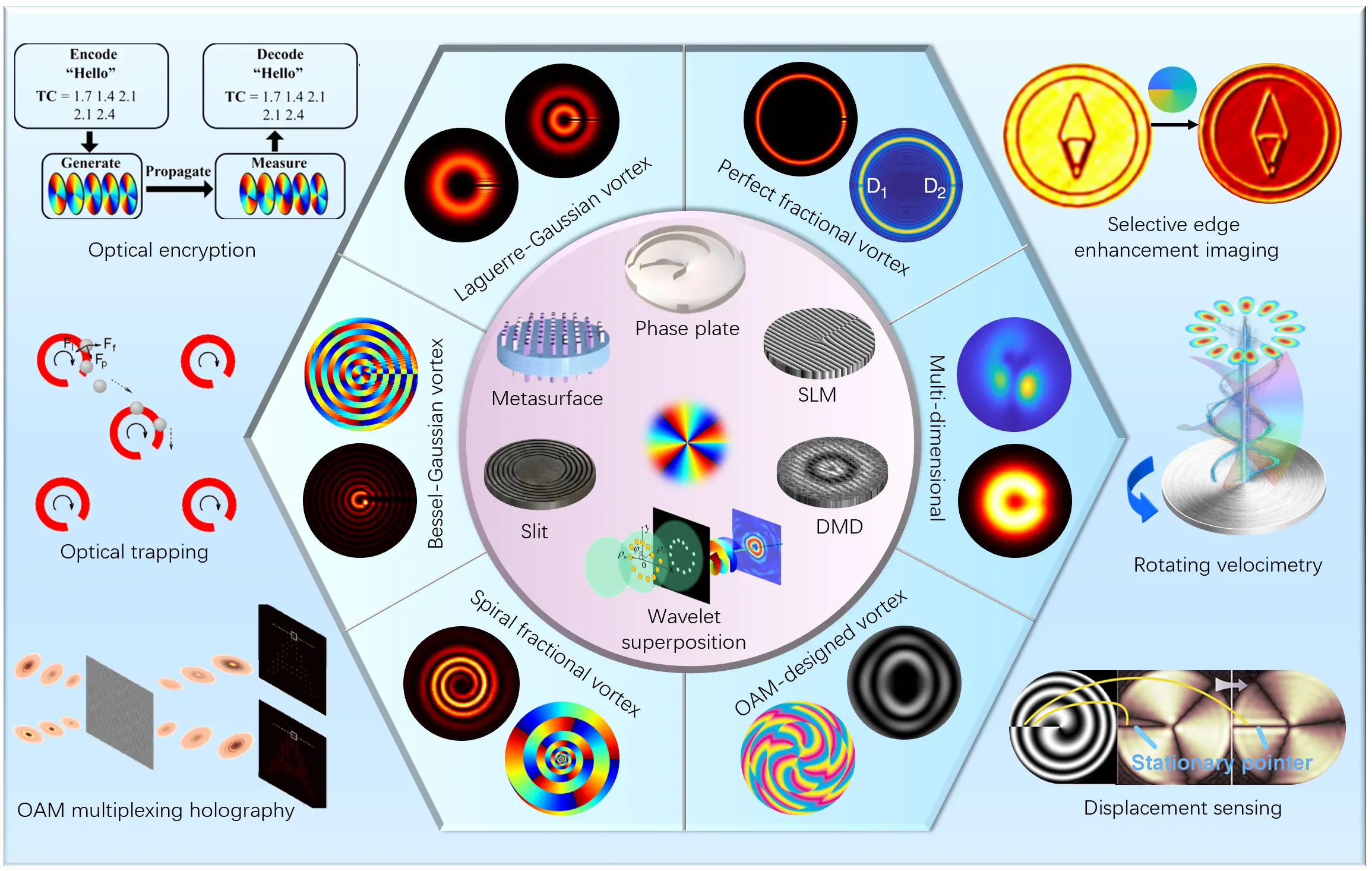

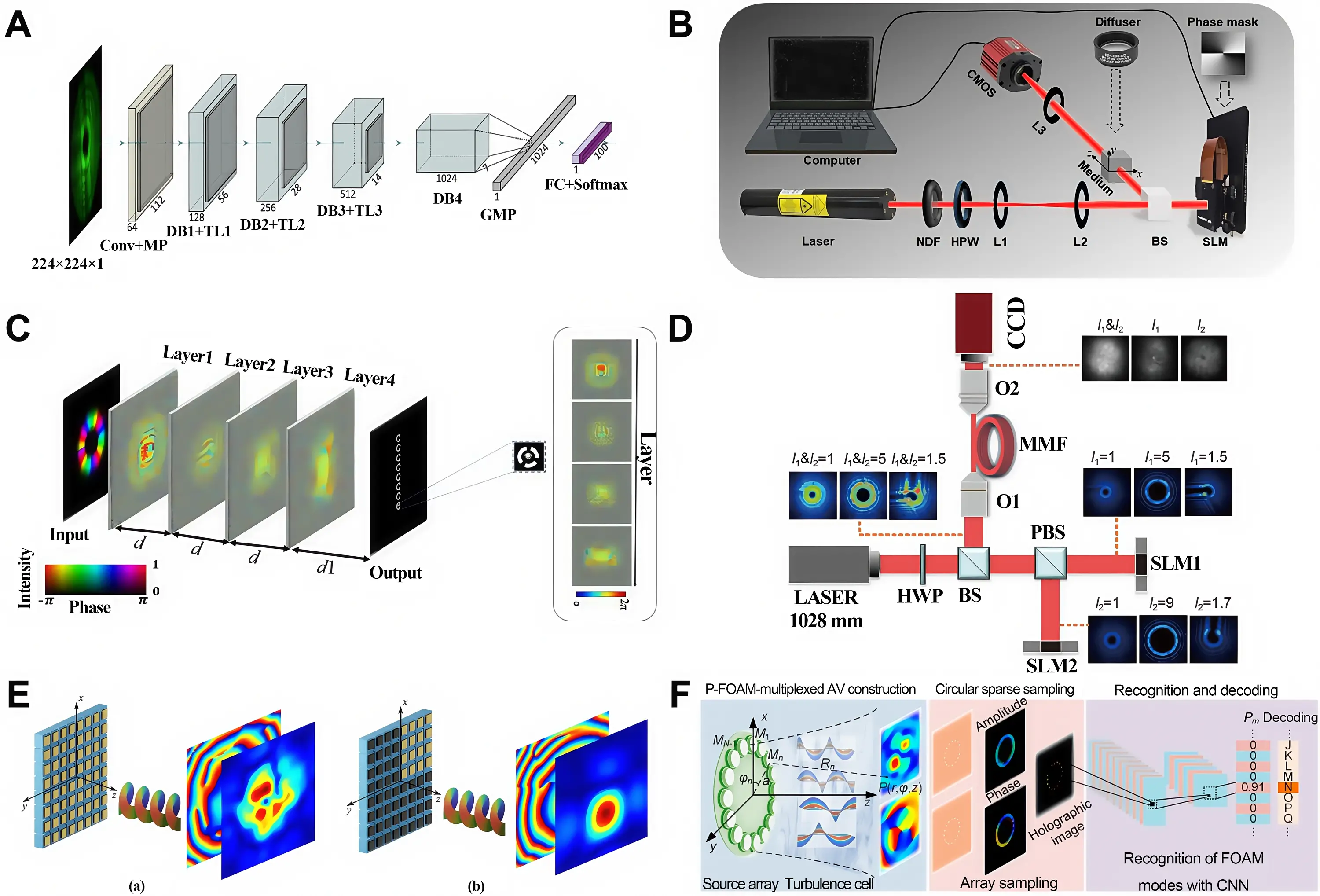

This review summarizes recent progress in the study of fractional vortex beams (Figure 1), covering theoretical models (Section 2), generation methods (Section 3), measurement techniques (Section 4), and applications (Section 5). The concept of fractional-order vortices has been extended from scalar, spatial, coherent, and visible-light regimes to vectorial, spatiotemporal[69], partially coherent[42,75], and acoustic fields[71,76,77]. Theoretical models based on modal superposition have deepened the understanding of the properties, generation, detection, and applications of fractional vortex beams[19,20]. To ensure compatibility across different physical platforms, a variety of generation schemes have been developed beyond programmable spatial light modulators (SLMs)[14,78,79], including diffractive elements ranging from conventional vortex phase plates[73,75,80,81] to advanced metasurfaces[82,83], coherent wavelet superposition[70,84], and on-chip generation for integrated photonics[85,86]. Accurate determination of the TC and OAM spectrum is essential for applications of fractional vortex beams. In addition to classical approaches based on diffraction through phase or amplitude masks[87,88], techniques such as optical field reconstruction[47,89] and modal-decomposition[90] have been employed for quantitative measurement of fractional TCs by enabling single-shot measurement of complex OAM spectra. Furthermore, advances in deep learning have significantly enhanced the speed and accuracy of fractional-order detection in both optical and acoustic vortices[54,91,92].

2. Theoretical Models

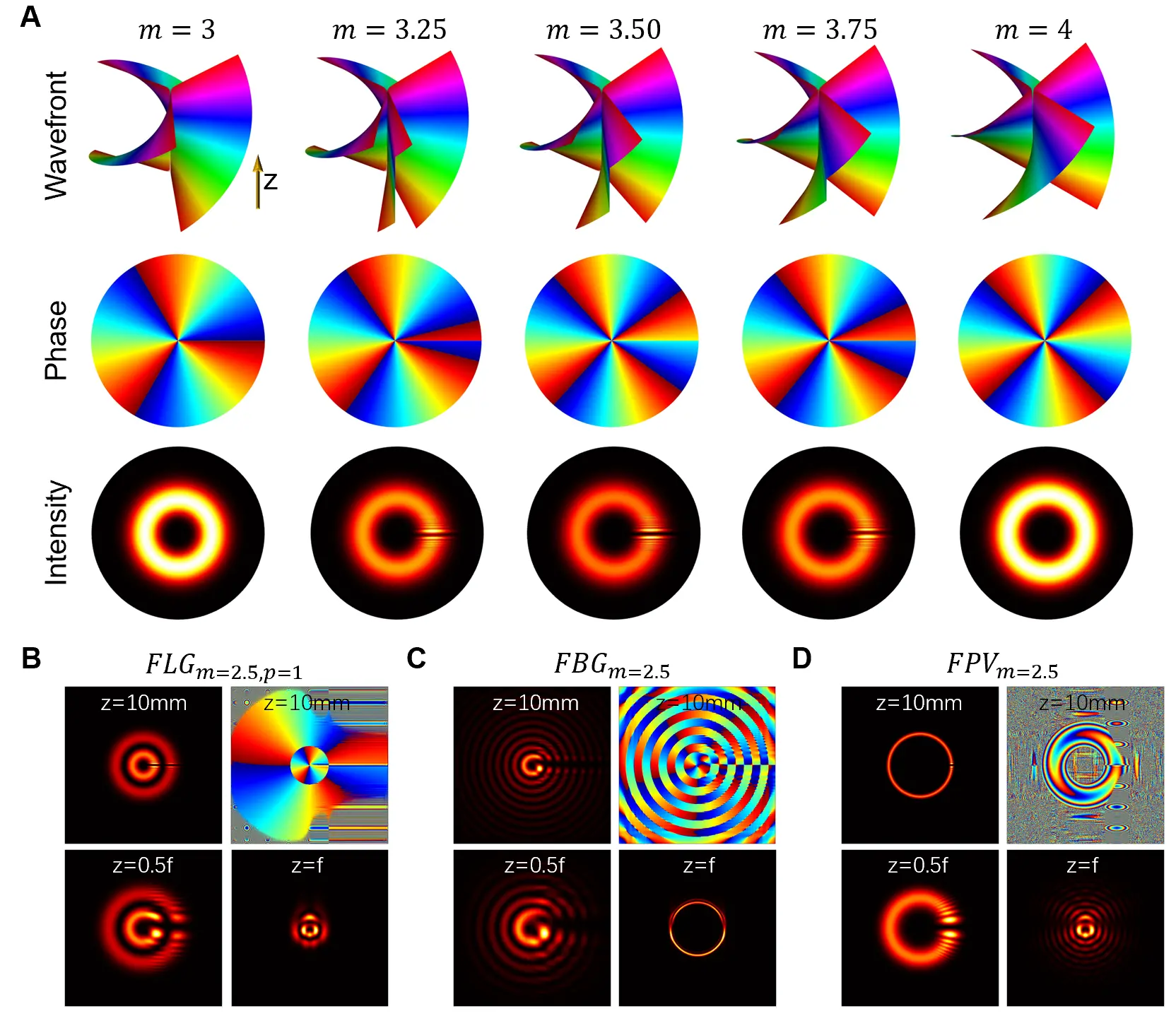

In contrast to optical vortices with integer TCs (azimuthal index), fractional vortex beams, characterized by non-integer TCs, exhibit a phase step (or phase jump) that is a non-integer multiple of 2π, as illustrated in Figure 2A, with the corresponding phase term expressed as exp(imθ). A typical intensity profile reveals an edge dislocation aligned with the fractional phase jump. The phase pattern further displays a chain of alternating vortices forming a dark line associated with this edge dislocation[13,74]. To facilitate the application and property design of fractional vortex beams, various models have been developed. A generic representation decomposes a fractional vortex into a superposition of vortices with different integer TCs[19,20], which is essential for understanding and modulating the propagation stability of such beams.

Figure 2. Typical phase and intensity patterns of fractional vortex beams. (A) Fractional Laguerre-Gaussian beam (p = 0) with various TCs near the source plane (z = 10 mm, w0 = 0.5 mm); (B) Fractional Laguerre-Gaussian beam at different propagation distances (w0 = 0.5 mm); (C) Fractional Bessel-Gaussian beam at different propagation distances (kr = 60, w0 = 1 mm); (D) Fractional perfect vortex beam at different propagation distances (w0 = 0.5 mm, R = 1 mm). The focal length is f = 150 mm.

2.1 Scalar and coherent fractional vortex beams

2.1.1 Conventional models

A fractional vortex beam generally refers to a vortex beam whose TC takes a non-integer value. A conventional coherent fractional vortex beam is defined as:

It can be further written as E(r,θ) = A(r,θ) · exp(ilmθ) · exp(iμθ). Here, m is a fraction, and thus the phase term exp(imθ) indicates a spiral phase with a non-integer winding number. m = lm + μ, where lm is the integer part of the fraction m, and the fractional part μ lies between 0 and 1. The function A(r,θ) is the complex-valued amplitude, and (r,θ) denotes the polar coordinates. By modifying the amplitude term, various types of fractional vortex beams can be defined, including plane-wave fractional vortex beams, Gaussian fractional vortex beams[10,11], fractional Laguerre-Gaussian beams[9,12,19,68,93], fractional Bessel beams[13,94,95], perfect fractional vortex beams[14,15,49], and so on.

When A(r,θ) is constant, Eq. (1) describes a plane-wave fractional vortex beam. In practice, beams of finite width are more common and amenable to numerical simulation and analytical treatment. A fractional Gaussian vortex can be written as[10]:

where w0 is the beam radius.

The fractional Laguerre-Gaussian beam model is widely used and expressed as[68]:

where A0 is the position-independent normalized constant, and

The fractional Bessel beam of order m is expressed as[13]:

A related model, the fractional Bessel–Gaussian beam, is written as[14]:

Here, kr is the radial wave number. Figure 2C shows the intensity distribution of the Fractional Bessel-Gaussian beam near the source plane and at the focal plane. When the TC m is non-integer, Eq. (4) is not a physically allowed solution of the Helmholtz equation[13]. Thus, a nondiffracting fractional Bessel beam is modeled as[95,96]:

where k is the transverse wave number and l is the integer ranging from -∞ to ∞. Jl denotes the l-th order Bessel function of the first type. Here, an additional Gaussian amplitude could be added in Eq. (6), written as

The expression for a fractional perfect vortex beam is derived from the Fourier transformation of the fractional Bessel beam in Eq. (5), written as[14]:

where wf = 2f/kw0 is the Gaussian beam waist at the focal plane, w0 is the beam waist of the Gaussian beam, f is focal length, and R determines the ring radius of the perfect fractional vortex beam. Figure 2D shows the intensity distributions of the fractional perfect vortex beam near the source plane and to the focal plane.

Beyond circularly symmetric models, a fractional elliptic vortex beam is defined as[97]:

where ϵ denotes the elliptic parameter. Similar transformations can be applied to perfect fractional vortices[14,49,98].

2.1.2 Multi-opening fractional vortex beams

To meet diverse application needs, functional fractional vortex beams with multiple phase discontinuities have been developed. A standard fractional vortex beam has one slit opening, but in the study of smooth “perfect fractional vortex beams”[15], the fractional phase discontinuity is distributed periodically, defined as:

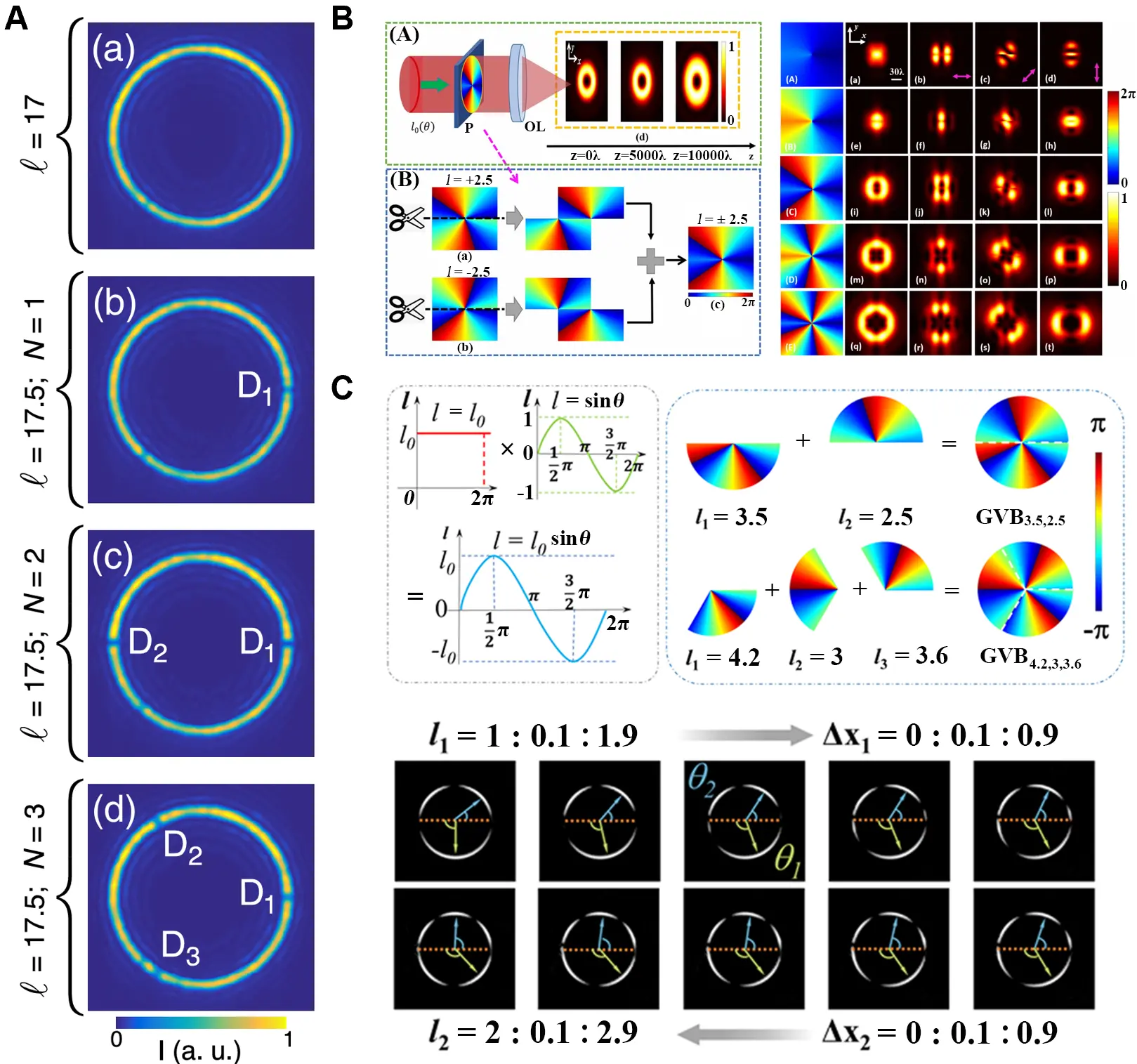

AB denotes a ring-shaped beam generated by an axicon, and N is the number of dislocations uniformly distributed along the ring. An example of m = 17.5 with 0, 1, 2, and 3 slit openings are shown in Figure 3A[15].

2.1.3 Grafted fractional vortex beams

Grafting techniques further enhance the modulation flexibility of fractional vortex beams[16,82,99], and the TC values of the grafted beam can even be opposite. A stable beam combining dual fractional vortex phases is illustrated in Figure 3B[16]. Recently, a fractional perfect vortex beam with a trigonometric-function TC was proposed[100], with its main phase term written as exp(imsinθ · θ). Then, the grafted perfect vector vortex beam with trigonometric-function TC was proposed for high-capacity optical encryption[82], as shown in Figure 3C.

2.1.4 Spiral fractional vortex beam

To increase holographic channel capacity, a fractional modulated chiro-optical vortex with an equiangular spiral shape was proposed[63,101]. A spiral fractional vortex beam avoiding holographic crosstalk is expressed as[17]:

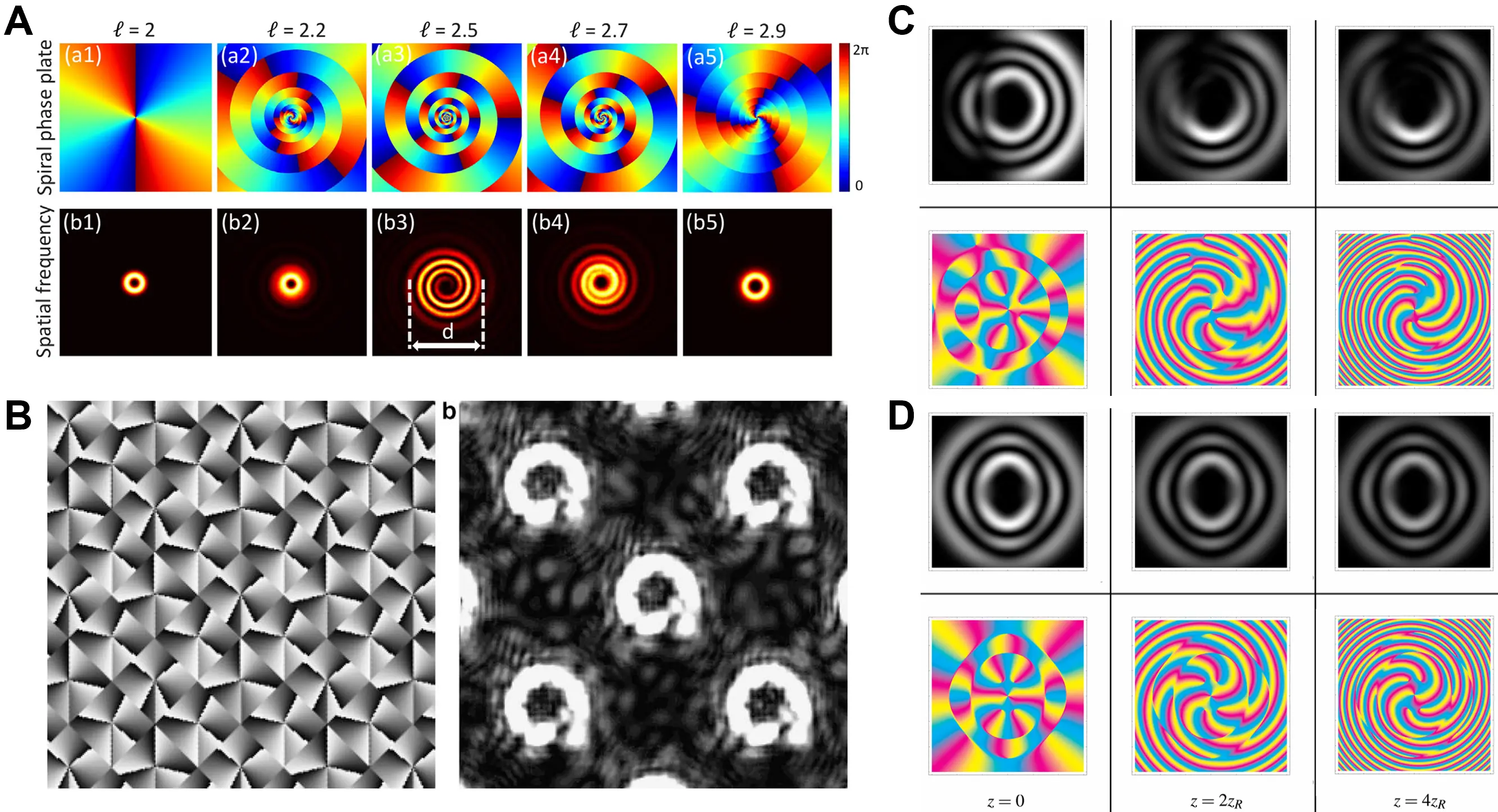

Figure 4A shows an example of the spiral fractional vortex beam. When the fractional part of the fractional TC is close to 1, the diameter of the spectral spot is smaller, whereas it becomes larger when the fractional part is close to 0.5.

Figure 4. Functional fractional vortex beams. (A) Spiral fractional vortex beams[17]; (B) Fractional vortex arrays (m = 3.5). Republished with permission from[18]; Fractional vortex beam (m = 6.5) superimposed with 5 Laguerre-Gaussian modes (C) with and (D) without the same Gouy phase. Republished with permission from[19].

2.1.5 Fractional vortex arrays

Fractional vortex arrays (Figure 4B) can be generated using a phase-only Talbot array illuminator, yielding high efficiency and compression ratio. Their complex-valued amplitude is written as[18]:

2.1.6 Coherent superposition of integer OAMs

Early studies described fractional Laguerre-Gaussian beams via modal decomposition[9,102]. The superposition is determined by a Fourier series, written as[20]:

Using a quantum-optical analogy, a fractional OAM state decomposes into integer OAM states[103]. A fractional OAM state with edge dislocation orientation α is expressed as[22,103]:

The angle θ0 defines the starting angle of the 2π radian interval. α is measured from θ0. μ is the fractional part of m. Obviously, the fractional OAM state|m(α)〉depends on the orientation of the discontinuity α. The probability of each integer OAM state is defined as:

One can also use the complete set of Laguerre-Gaussian modes

Cn is the same as Eq. (13). The Gaussian spot size

The Gouy phase term exp[-i(2p + |m| + 1)tan-1(z/zR)] differs across modes. One can limit the number of different Gouy phases to two: one for even TC values and one for odd values, by setting the mode index p for each n in the superposition as:

N is the total number of superimposed modes. Floor(q) gives the nearest integer smaller than, or equal to, q.

A uniform Gouy phase can be achieved by superposing two fractional LG states with a π difference in the orientation α, written as:

For an even integer part of m, the state |m+(α)〉gives a superposition of even modes, while for an odd integer part of m, the decomposition contains only odd modes. Its structure stability (Figure 4C,D) makes these beams ideal for quantum information processes utilizing fractional OAM states[19].

2.2 Partially coherent fractional vortex beam

In addition to fully coherent and monochromatic beams with wave-front singularities, partially coherent light fields, which may not have intensity zeros, also contain singularities[47,104]. Numerous studies in spatially incoherent monochromatic vortex beams have been proposed[4,104-115], including the partially coherent fractional vortex beam[42,75].

To generate a partially coherent vortex beam, a typical way is assuming that the cross-spectral density function has the Gaussian Schell-model form[116], in which the intensity part is based on the Laguerre-Gaussian modes or other vortex beams, but the degree of coherence can be chosen as simple Gaussian. A physically genuine cross-spectral density function of the partially coherent light field can be expressed in the following form[117]:

p(v) is a nonnegative function and H(r,v) is an arbitrary kernel. By setting

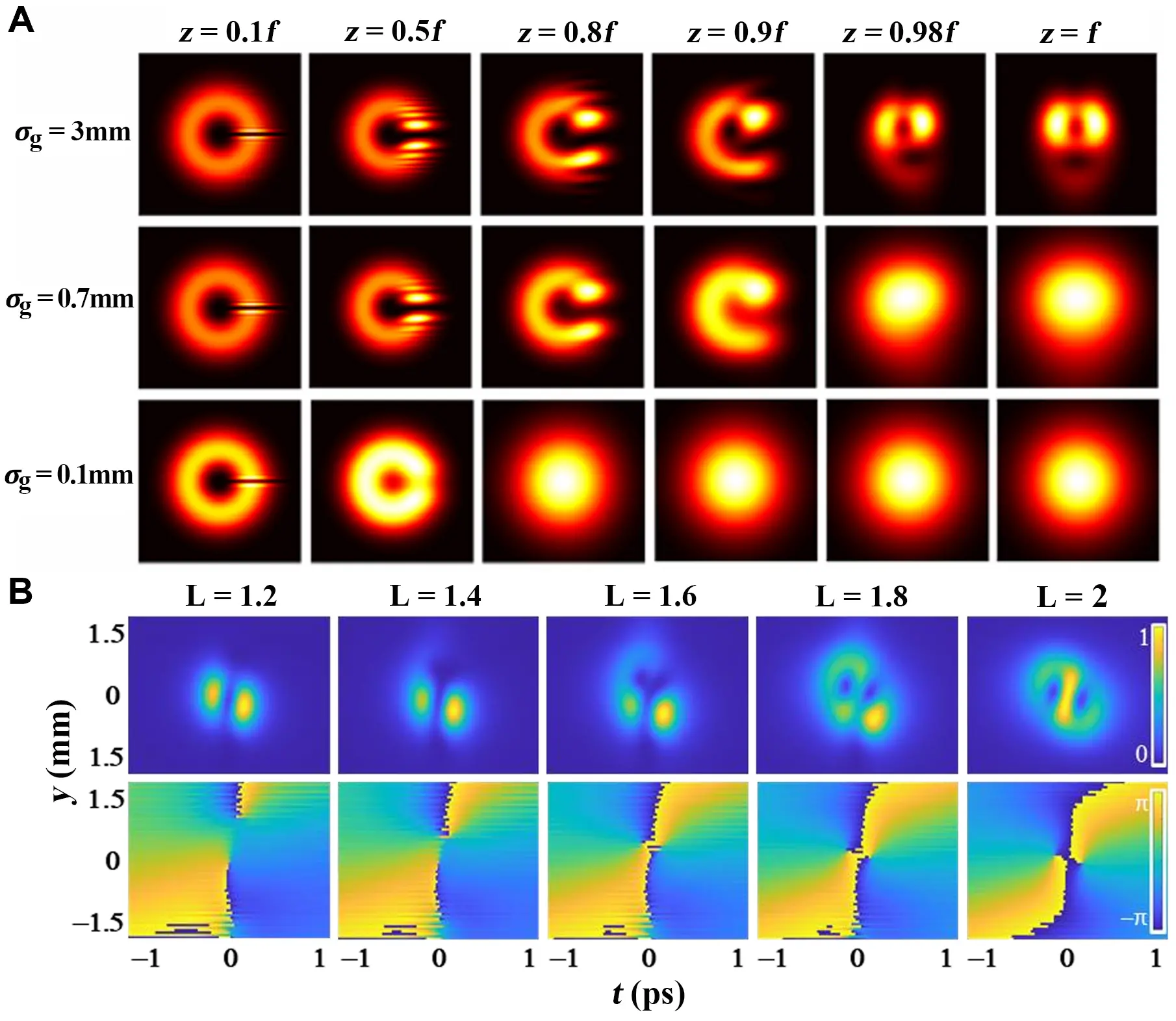

The difference of fractional vortex propagation of high and low degree of coherence can be found in Figure 5A. The slit opening toward the focal plane disappears gradually with the decrease of coherence.

2.3 Fractional spatiotemporal optical vortices

The electric field of an m-th order spatiotemporal optical vortex at the source plane is given by[118]:

where E0(x,y,t) is a Gaussian pulse, and t0, y0 are temporal and spatial scale widths. To better describe the fractional spatiotemporal optical vortex generated using a 4f pulse shaper[69], a fractional spiral phase is loaded onto the Fourier plane to modulate the input Gaussian pulse, written as:

The time-domain field is obtained via Fourier transform:

Figure 5B shows intensity and phase patterns of fractional spatiotemporal optical vortices with m =1.2:0.2:2.

In brief, fractional vortex beams have been described using various models, which can be categorized into fundamental and functional types. Continuous and fractional TCs show potential for applications in high-dimensional optical encryption and quantum entanglement, and have also been employed to enhance information capacity in OAM multiplexing holography. To mitigate crosstalk, spiral fractional vortex beams have been used. Most fractional vortex beams exhibit a fractional 2π phase jump. A typical and widely used model is the fractional Laguerre–Gaussian beam, whose fractional 2π phase jump enables tunable edge enhancement in imaging. When such beams propagate through a system with a limited aperture or over a distance, this phase jump also leads to an opening slit in the imaging or propagation plane, facilitating applications in optical tweezers and displacement sensing. Other representative examples include the fractional perfect vortex beam and its derivatives, such as multi-opening fractional vortex beams and grafted fractional vortex beams. Compared with integer-order vortex beams, fractional vortex beams are characterized by a broadened OAM spectrum. This feature, counterintuitively, offers advantages for rotational velocity measurement, but also introduces a major drawback: propagation instability. This issue can be addressed by using fractional Bessel beam models or coherent superposition models with Gouy phase correction. For modulating the light profile, coherence and temporal degrees of freedom offer additional avenues for control. A comprehensive overview of these applications is provided in Section 5 of this manuscript.

3. Generation of Fractional Vortices

The generation of fractional vortex beams can be realized through various approaches, yet the central objective remains the precise construction of a phase structure with fractional TCs, while ensuring the stability and controllability of the optical field during propagation and application. Depending on experimental conditions and application requirements, the methods can be broadly categorized into three types: programmable generation using SLMs[14,119], diffractive elements[75,80] including vortex phase plates and advanced metasurfaces[73,81-83], and coherent wavelet superposition[71,84,120,121]. These approaches range from digitally tunable schemes to physically fixed designs with high stability and are increasingly extending toward miniaturized, integrated implementations. This section discusses the physical principles, implementation strategies, and the comparative advantages and limitations of each method, providing the groundwork for subsequent measurements and applications.

3.1 Spatial light modulator

SLMs are widely used for generating fractional vortex beams owing to their high flexibility and programmability. They are capable of modulating the amplitude, phase, or polarization state of light, making them particularly suitable for laboratory demonstrations and rapid prototyping. Commercial liquid-crystal SLMs typically provide continuous phase modulation over a 0-2π range at designated wavelengths, with grayscale levels mapped linearly to phase delays. Digital micromirror devices (DMDs), by contrast, operate via binary amplitude modulation using independently addressable micromirrors, offering higher switching speeds and reflectivity[122,123]. For amplitude-type SLMs or DMDs, fractional vortex beams are commonly generated using the fork-grating holography method, which relies on the interference between a fundamental Gaussian beam EG(r,θ) and a target fractional vortex beam ET(r,θ). The resulting hologram can be expressed as:

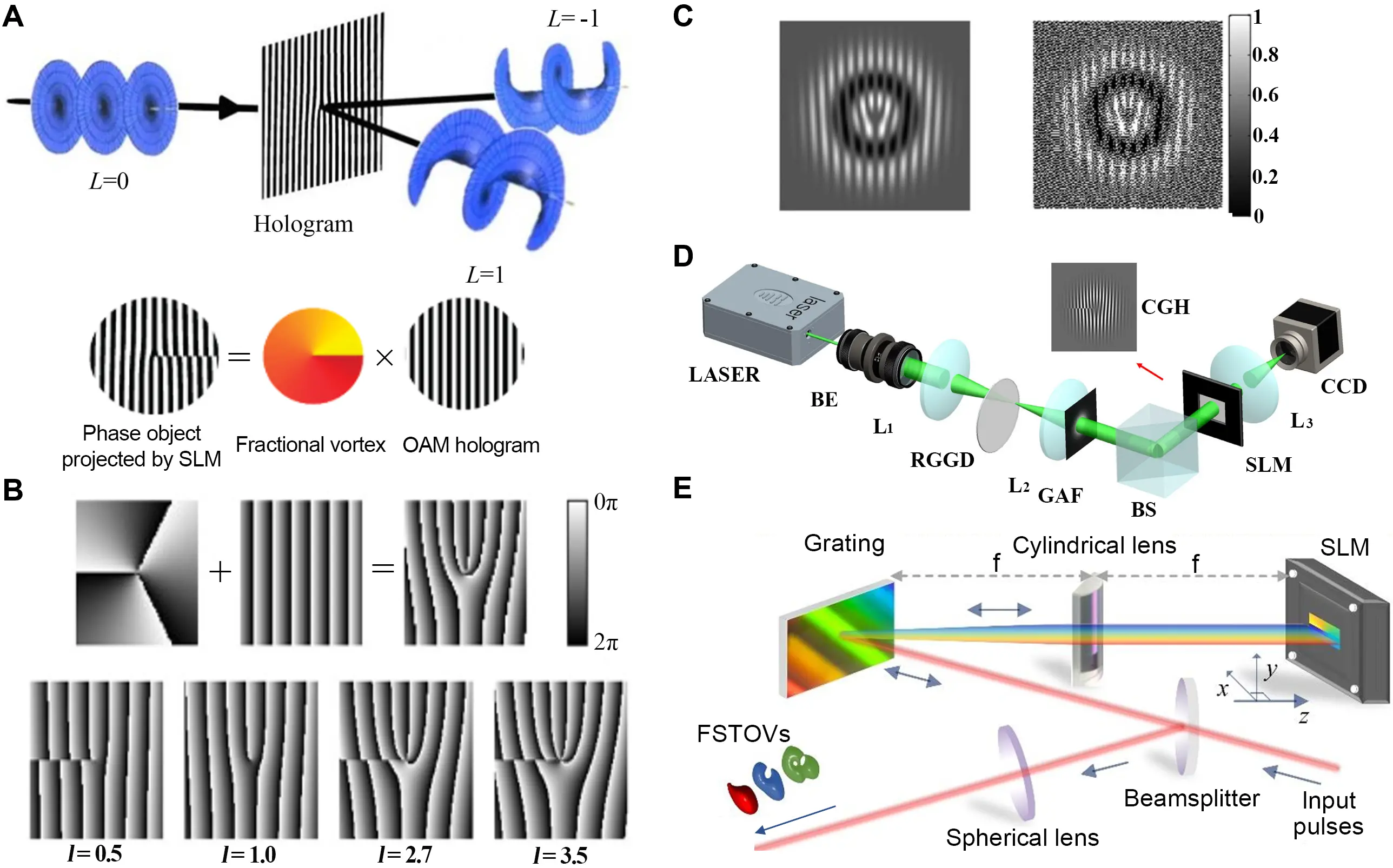

where G is the parameter related to the grating spatial frequency. When this hologram is loaded onto an amplitude-modulating device, the encoded fractional vortex beam can be reconstructed in the diffraction field, as illustrated in Figure 6A[79].

Figure 6. Fractional vortex beam generation with spatial light modulator or digital micromirror device. (A) Amplitude-type spatial light modulator loaded with a fork grating[79]; (B) Holograms loaded on the phase-only spatial light modulator[14]; (C) Binary hologram for digital micromirror device. Republished with permission from[123]; (D) Experimental setup for generating a partially coherent fractional vortex beam[42]; (E) Experimental setup for the generation of fractional spatiotemporal optical vortex pulses. Republished with permission from[69]. SLM: spatial light modulator; OAM: orbital angular momentum; BE: beam expander; RGGD: rotating ground-glass disk; GAF: Gaussian amplitude filter; BS: beam splitter; CGH: computer-generated holograms; CCD: charge-coupled device.

Phase-only SLMs enable more efficient generation of fractional vortex beams by directly encoding the fractional spiral phase term exp(imθ) onto the device[78]. In practice, imperfect pixel fill factors introduce residual zero-order light, which degrades beam purity. This effect is commonly mitigated by superimposing a linear grating to spatially separate the desired vortex beam from the unmodulated component (Figure 6B)[14]. Phase-only SLMs can also implement complex-valued holograms based on iterative or analytical algorithms[122], while DMD-based implementations require binarization of the hologram[123] using dithering techniques[124] (Figure 6C). Beyond fully coherent scalar beams, SLMs have been successfully extended to generate partially coherent fractional vortex beams by combining computer-generated holography with rotating ground-glass modulation[42] (Figure 6D). They have also been employed to generate fractional spatiotemporal optical vortices by imprinting fractional spiral phases at the Fourier plane of the pulse shaper[69] (Figure 6E). These capabilities highlight the versatility of SLM-based approaches across different coherence regimes and spatiotemporal degrees of freedom, despite inherent limitations in efficiency and pixel-induced artifacts.

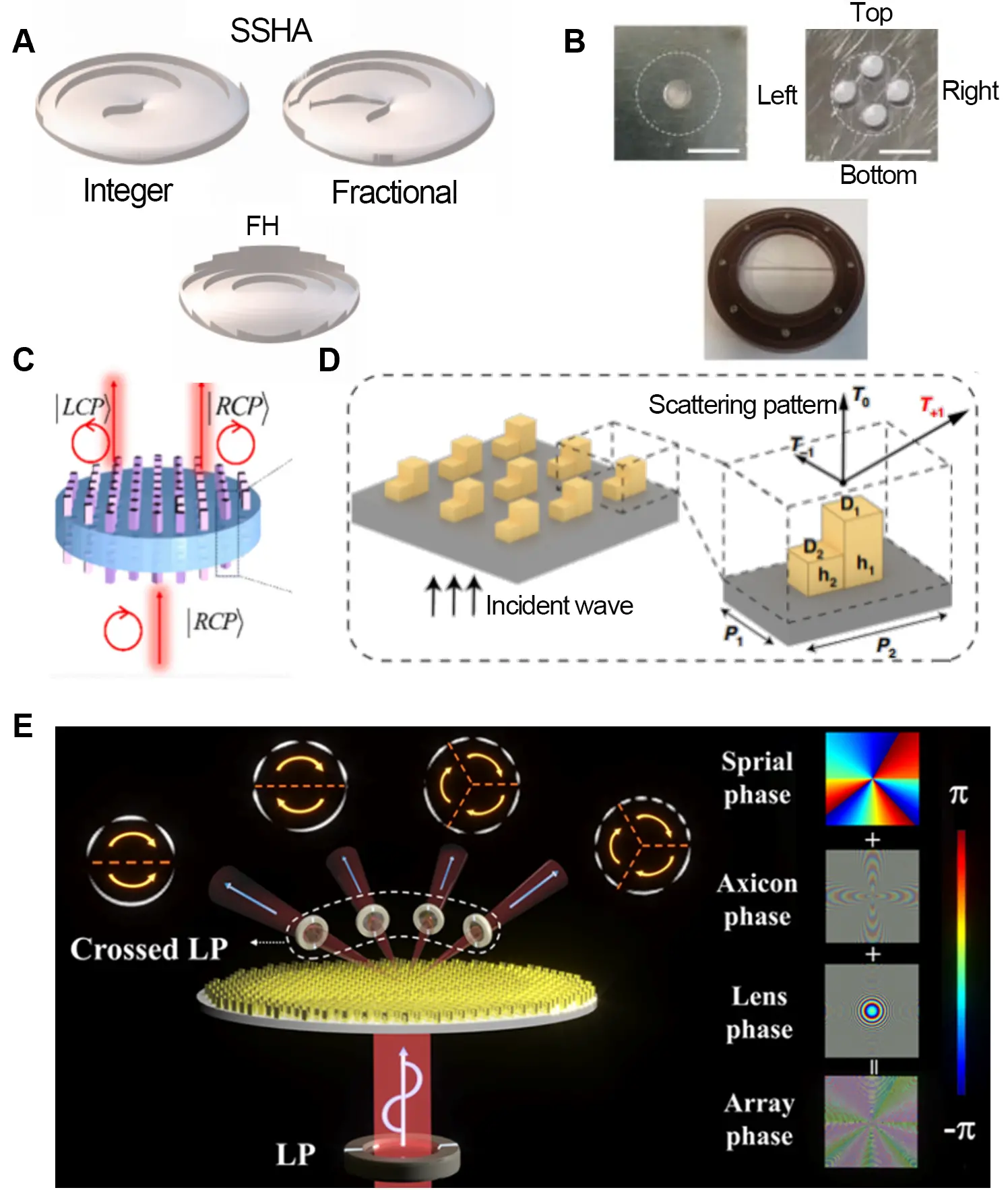

3.2 From vortex phase plates to metasurface

One of the earliest approaches for generating fractional vortex beams employs vortex phase plates (or spiral phase plates), which introduce a helical phase profile by implementing a spiral-shaped thickness distribution in a transparent optical substrate. As illustrated in Figure 7A, the thickness varies linearly with the azimuthal angle, producing a total phase delay of ∆Φ = 2πm over a full rotation. This concept can be naturally extended to continuous and fractional TCs, although the realization of fractional vortex beams places stringent demands on fabrication accuracy. Advanced nanofabrication techniques, including direct laser writing, grayscale mask lithography, and femtosecond laser inscription, have enabled the implementation of engineered thickness profiles with arbitrary phase delays. Vortex phase plates are valued for their structural simplicity, high optical efficiency, and polarization insensitivity, which make them attractive for fixed and long-term stable optical systems. However, the lack of tunability after fabrication, combined with pronounced wavelength dependence that yields different effective TCs at different wavelengths[42,75], significantly limits their versatility. These constraints are particularly evident in broadband or reconfigurable systems, despite successful demonstrations in regimes such as terahertz vortex generation using spiral phase plates combined with metallic masks (Figure 7B)[81].

Figure 7. Generation of fractional vortex beams using spiral phase plates and metasurfaces. (A) Generation with frequency multiplexing in the terahertz band using a vortex phase plate and a metallic mask. Republished with permission from[73]; (B) Generation of a terahertz fractional vortex beam via a spherical spiral axicon[81]; (C) Double-layer dielectric metasurface optimized with machine learning. Republished with permission from[72]; (D) Metamaterial module integrated with a metalens module fabricated via 3D-printing[83]; (E) Generation of a perfect vectorial fractional vortex beam using an all-dielectric geometric metasurface. Republished with permission from[82].

With the rapid advances in nanophotonics and artificial micro-structuring, metasurfaces have emerged as a powerful planar platform for the generation and manipulation of fractional vortex beams, offering enhanced flexibility, compactness, and integrability[82]. Composed of subwavelength-spaced nanoantennas or dielectric meta-atoms, metasurfaces enable precise wavefront control by tailoring the local geometry, orientation, and material properties of individual unit cells. Through appropriate design, they can impart either continuous or discretized phase modulation, efficiently converting incident plane waves or Gaussian waves into vortex beams. Metasurface designs based on Jones matrix formalism, machine-learning optimization[72], and cascaded metamaterial-metalens architectures[83] have further enabled multifunctional control and switching of vortex states (Figure 7C,D). In particular, geometric-phase (Pancharatnam–Berry phase) strategies enable non-integer 2π phase accumulation over a full azimuthal cycle by controlling the orientation of anisotropic nanostructures. This capability facilitates the generation of complex fractional vortex fields with asymmetric intensity distributions and localized phase discontinuities (Figure 7E). Owing to their subwavelength resolution and design versatility, metasurfaces generally provide superior wavefront quality and high spatial resolution compared with conventional spatial light modulators or vortex phase plates. In addition, their broadband operation makes them particularly attractive for integrated and on-chip photonic systems. Their demonstrated applicability across spectral ranges from the visible and near-infrared to the soft X-ray regime further highlights the potential of metasurfaces as a key enabling technology for fractional vortex beam generation.

3.3 Coherent wavelet superposition

In certain specific wavelength bands, such as the mid-infrared band, the corresponding optoelectronic devices like spatial light modulators are lacking, making it hard to directly employ the above-mentioned methods to generate fractional vortex beams. Furthermore, for special types of vortices such as acoustic vortices, traditional optical components cannot be directly applied to their generation process. Consequently, coherent wavelet superposition has emerged as a feasible and necessary pathway, which has enabled the generation of fractional vortices in visible light (Figure 8A,B,C)[84,120], terahertz waves[121], and even acoustic waves (Figure 8D)[71], overcoming the limitations of traditional optoelectronic devices.

Figure 8. Generation of fractional vortices using coherent wavelet superposition. (A) Generation of a fractional optical vortex beam via coherent wavelet superposition from a spiral slit[125]. Republished with permission from[126]; (B-C) Diffractive modulation method for generating fractional vortex beams using an ordered pinhole screen[70]. Republished with permission from[84]; (D) Generation of a fractional acoustic vortex via coherent superposition of wavelets transmitted through multiple discrete Archimedean spiral slits engraved on an artificial structure plate. Republished with permission from[71].

Coherent wavelet superposition involves the spatial synthesis of multiple coherent wavelets to form a target field. Ideally, these wavelets share the same frequency and maintain fixed phase relationships, resulting in stable interference phenomena in the superposition region. Through coherent wavelet superposition, the overall intensity of the synthesized field can be effectively enhanced. Suppose the complex amplitudes of the n-th coherent wavelet at spatial position r and time t are En(r,t). Then, the superimposed complex amplitude with N wavelets can be expressed as the vector sum of the wavelets:

Here, An(r) denotes the spatial amplitude distribution of the n-th wavelet. ω is the angular frequency of the wave. For optical waves, ω = 2πc/λ (with c being the speed of light in vacuum and λ the wavelength). For acoustic waves, ω = 2πv/λ (with v being the speed of sound in the medium), and αn represents the initial phase difference between wavelets.

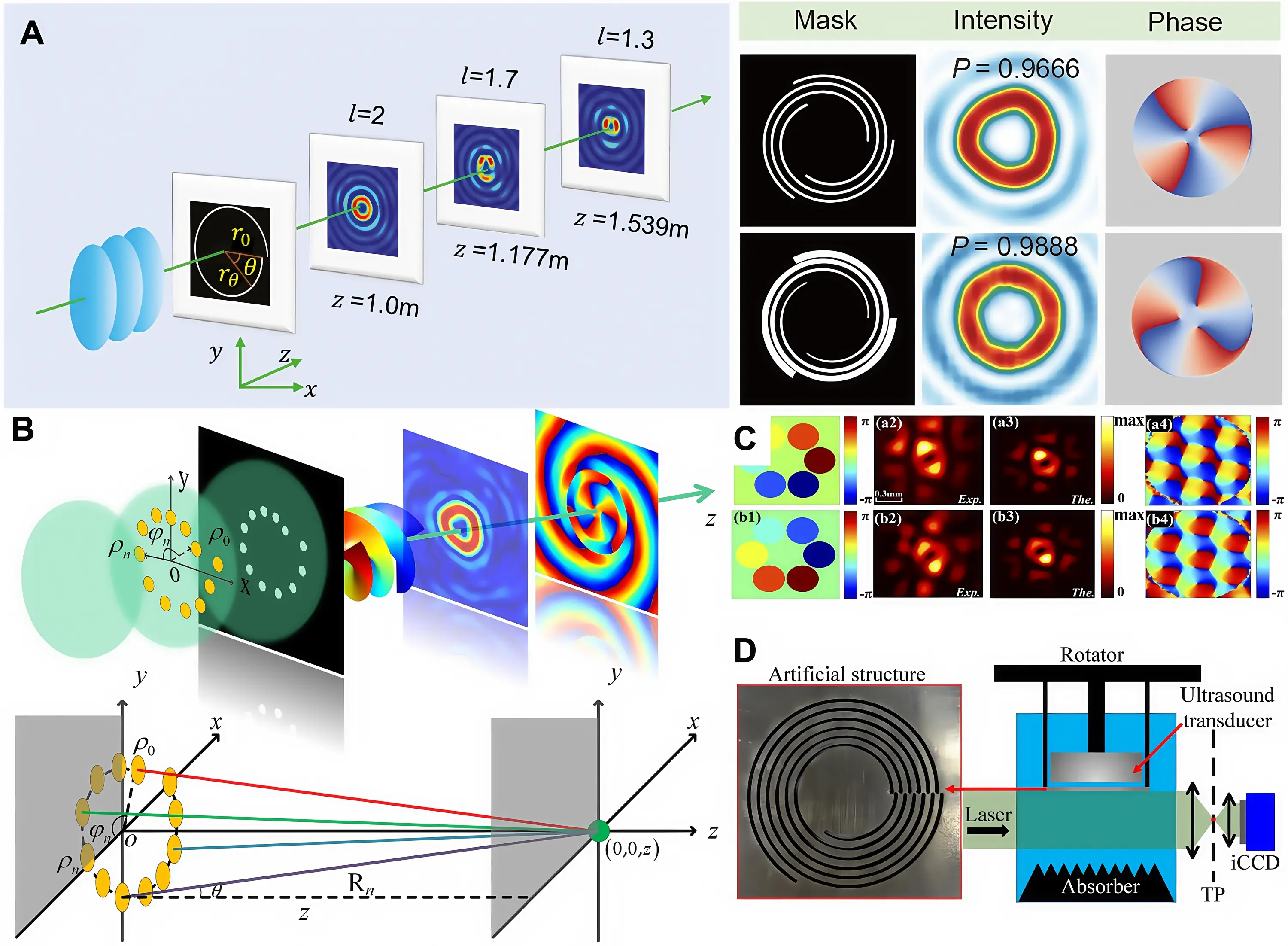

Figure 8A demonstrates the generation of a fractional vortex beam via coherent wavelet superposition from all point sources within a uniform or non-uniform spiral slit, in which the TC can be controlled based on the relationship[125,126]:

where r0 is the initial radius of the spiral slit, rθ are the radial and angular coordinates of the Fermat spiral slit.

Similarly, in Figure 8B, a spiral pinhole screen is employed to modulate the TC of an incident vortex beam. The helical arrangement of pinholes facilitates wavefront reconstruction, allowing for controlled increase or decrease of the TC and the generation of complex gear-like intensity profiles. This method eliminates the need for complex phase elements, offering a low-cost, highly flexible approach suitable for applications such as optical communications and encryption. Figure 8C also shows that a six-channel fiber laser array, together with programmable liquid crystal phase modulators, enables real-time control of the piston phase in each channel, thereby generating fractional vortex beams with tunable TCs ranging from -2/3 to +2/3[84]. As shown in Figure 8D, a discrete Archimedean spiral slit structure plate is used to generate fractional acoustic vortices. The principle is similar to the spiral slit used in light fields. Furthermore, it can also be generated from broadband terahertz vortex beams through a four-wave superposition process arising from the interaction between a two-color laser field with fractional TCs and air[121]. By adjusting the initial TCs combination, THz vortex beams with either fractional or integer TCs can be produced. Notably, in the case of a half-integer TC, the birth and annihilation of vortex pairs occur during propagation, revealing unique evolutionary dynamics.

3.4 Outlook for on-chip generation with integer-OAM superposition

Recent advances in integrated photonics, particularly the fusion of optical microcombs and vortex emission, have opened a completely new pathway for generating and manipulating light fields carrying complex OAM structures. Although these technologies have so far primarily demonstrated integer OAM states, their core principle, the parallel manipulation of multiple OAM modes in the frequency domain, offers an unprecedented platform for realizing truly dynamic fractional vortex beams.

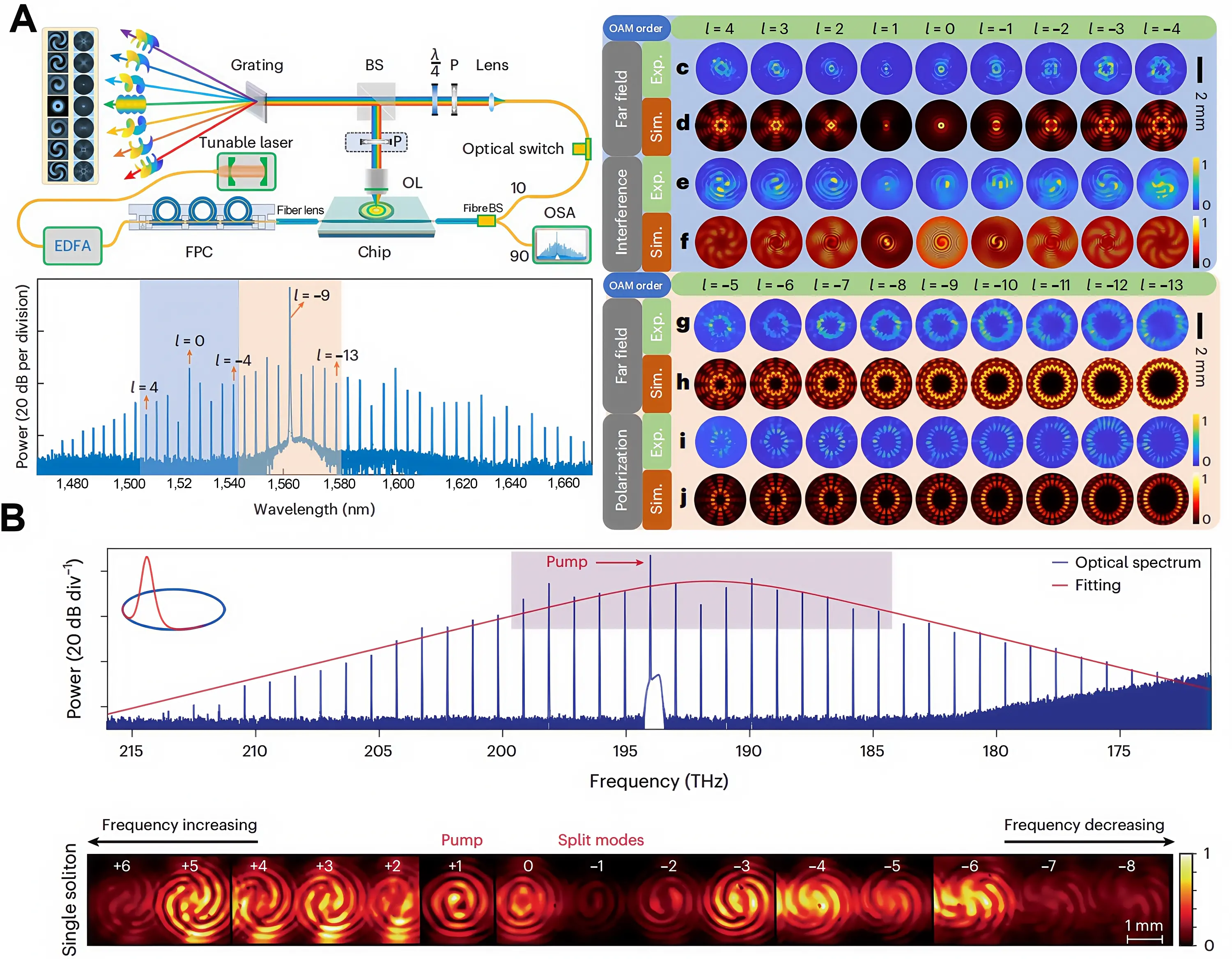

As shown in Figure 9, Chen et al.[85] and Liu et al.[86] demonstrated integrated optical vortex microcomb sources based on AlGaAs and Si3N4 platforms, respectively. These implementations utilize a single microring resonator simultaneously as a frequency comb generator and a vortex beam emitter. The resulting device is capable of outputting up to 50 discrete coherent optical vortices, with each comb line carrying a distinct integer TC. These advancements illustrate that parallel control of multiple integer OAM modes in the frequency domain offers a highly promising integrated pathway for synthesizing arbitrarily complex fractional topological structures in either the temporal or spatial domain. This approach circumvents the speed limitations inherent in the point-by-point programming of spatial light modulators by leveraging well-established optical frequency comb manipulation techniques, thereby laying the groundwork for high-speed, high-fidelity dynamic generation and application of fractional vortices. In the future, through precise definition of the amplitude and phase of the OAM modes within the frequency comb, it might be possible to synthesize on-demand optical fields with specific fractional TCs, thereby introducing new capabilities to fields such as quantum communications, optical micromanipulation, and super-resolution imaging.

Figure 9. On-chip generation of an OAM comb. (A) Schematic of the experimental setup and results for generating an OAM frequency comb using an AlGaAs-on-insulator-based nonlinear micro-ring resonator. Republished with permission from[85]; (B) Experimental results of an OAM frequency comb generated using a high-Q nonlinear ring micro-resonator on a thin-film substrate. Republished with permission from[86]. OAM: orbital angular momentum. BS: beam splitter.

3.5 Comparisons and discussions

Table 1 provides a comparative overview of representative generation methods for fractional vortex beams, covering efficiency, quality, applicability to different models, dynamic tunability, key advantages, and major limitations. Beyond implementation flexibility and system integration, wavelength dependence constitutes a key practical consideration across different generation platforms for fractional vortex beams. For vortex phase plates, the imposed helical phase arises from a fixed optical path length difference determined by the physical thickness profile. As a result, the effective TC varies with wavelength, which confines their applicability mainly to narrowband or single-wavelength systems. Metasurfaces significantly expand the design space by enabling dispersion engineering through tailored meta-atom geometries and material selection. This capability allows broadband or quasi-achromatic operation within a targeted spectral window, albeit with inherent trade-offs among bandwidth, conversion efficiency, polarization sensitivity, and fabrication tolerance. In contrast, generation schemes based on coherent wavelet superposition synthesize fractional vortex fields through controlled modal superposition, rather than wavelength-specific phase accumulation. This approach provides enhanced spectral flexibility and scalability for broadband, multiwavelength, and ultrafast applications.

| Generation method | Efficiency | Quality | Various models | Dynamic tunability | Advantages | Practical limitations |

| Vortex phase plates | High | High | No | No | High efficiency | Wavelength dependence |

| Metasurface | High | High | Yes | No | Integration, diversity | Polarization sensitivity |

| SLM/DMD | Moderate | High | Yes | Yes | Dynamic tunability | Diffraction efficiency |

| Coherent wavelet superposition | Low | Moderate | No | No | Multi-band versatility | Quality and efficiency |

SLM: spatial light modulator; DMD: digital micromirror device.

In summary, these generation methods show that fractional vortex beams can be generated through fundamentally distinct physical mechanisms. These include wavelength-dependent phase accumulation, wavelength-independent modal superposition, and broadband metasurface engineering, each offering unique advantages and facing specific limitations (Table 1). From a practical standpoint, however, fractional vortex beams are inherently sensitive to experimental imperfections and alignment errors during generation. This sensitivity stems from their non-eigenmode nature and their dependence on the coherent superposition of multiple integer-order OAM modes. Non-ideal factors, including phase discretization of modulation devices, aberrations, finite pixel fill factors, and slight misalignment of optical components, can perturb the relative amplitudes and phases of constituent modes. As a result, the intended phase discontinuity may be distorted and the OAM spectrum redistributed. Compared with integer-order vortex beams, which often preserve their topological structure under moderate perturbations, fractional vortex beams may therefore exhibit reduced robustness, particularly over long propagation distances or complex optical paths. Thus, reliable characterization of the complex field structure and OAM spectra becomes an essential complement to beam generation, thereby motivating the development of accurate and robust measurement strategies.

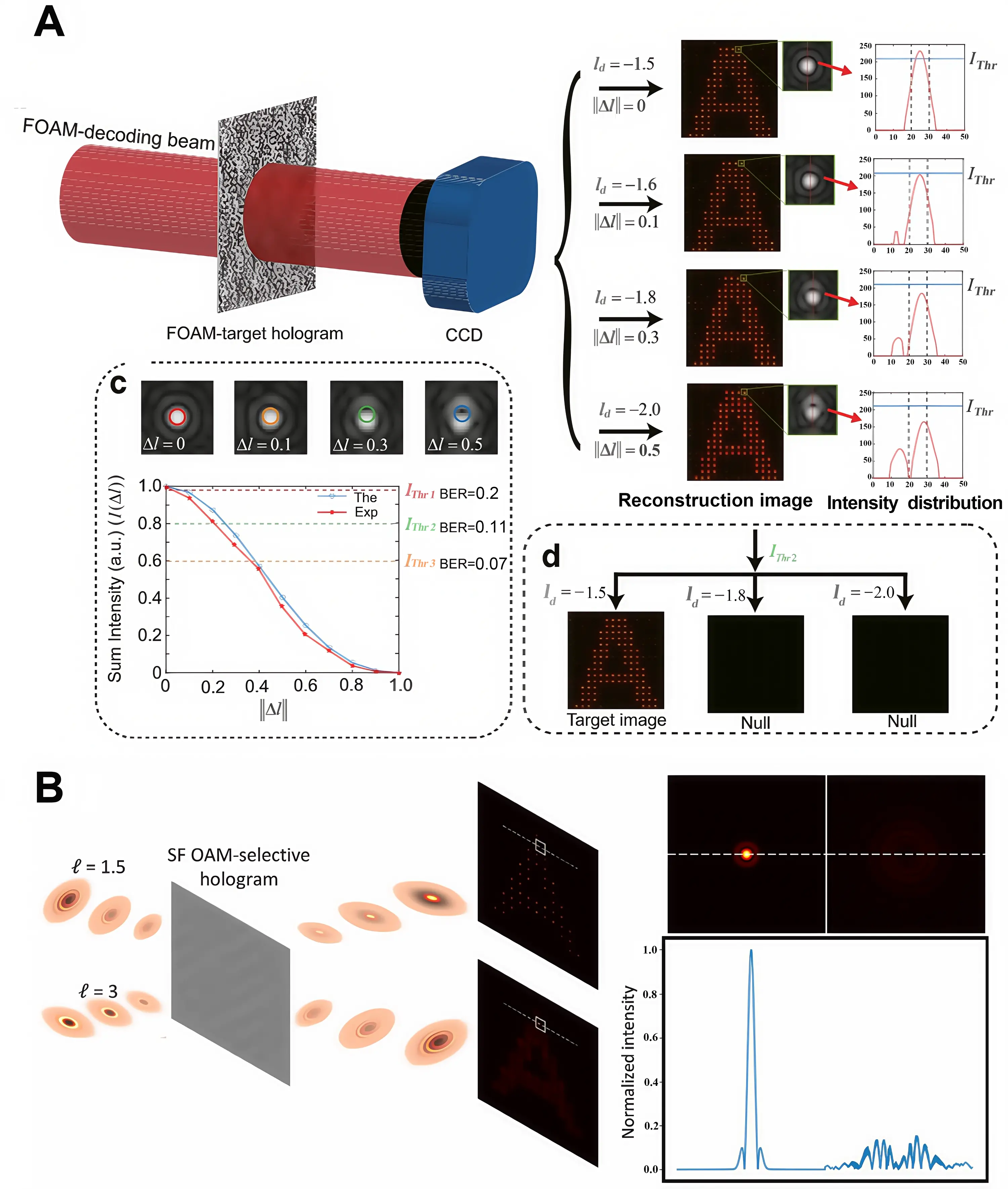

4. Measurement

TC measurement for fractional vortex beams plays an important role in both fundamental research and practical applications, such as quantum-key distribution[66,67], optical micromanipulation[15,18,28-31,127], holographic encryption[47-50], and optical imaging[11,32-38]. In this section, we have reviewed recent advances in fractional TC measurement from the perspectives of intensity analysis, optical field reconstruction, and deep-learning methods, etc.

4.1 Diffraction through phase or amplitude mask

Diffraction through phase and amplitude components is widely used in TC measurement of integer vortex beams. By “disrupting” the symmetry of the vortex beam, the distribution of the output optical field will be related to the TC or OAM spectrum. Based on theoretical fitting, it can be deduced to achieve vortex beam measurement.

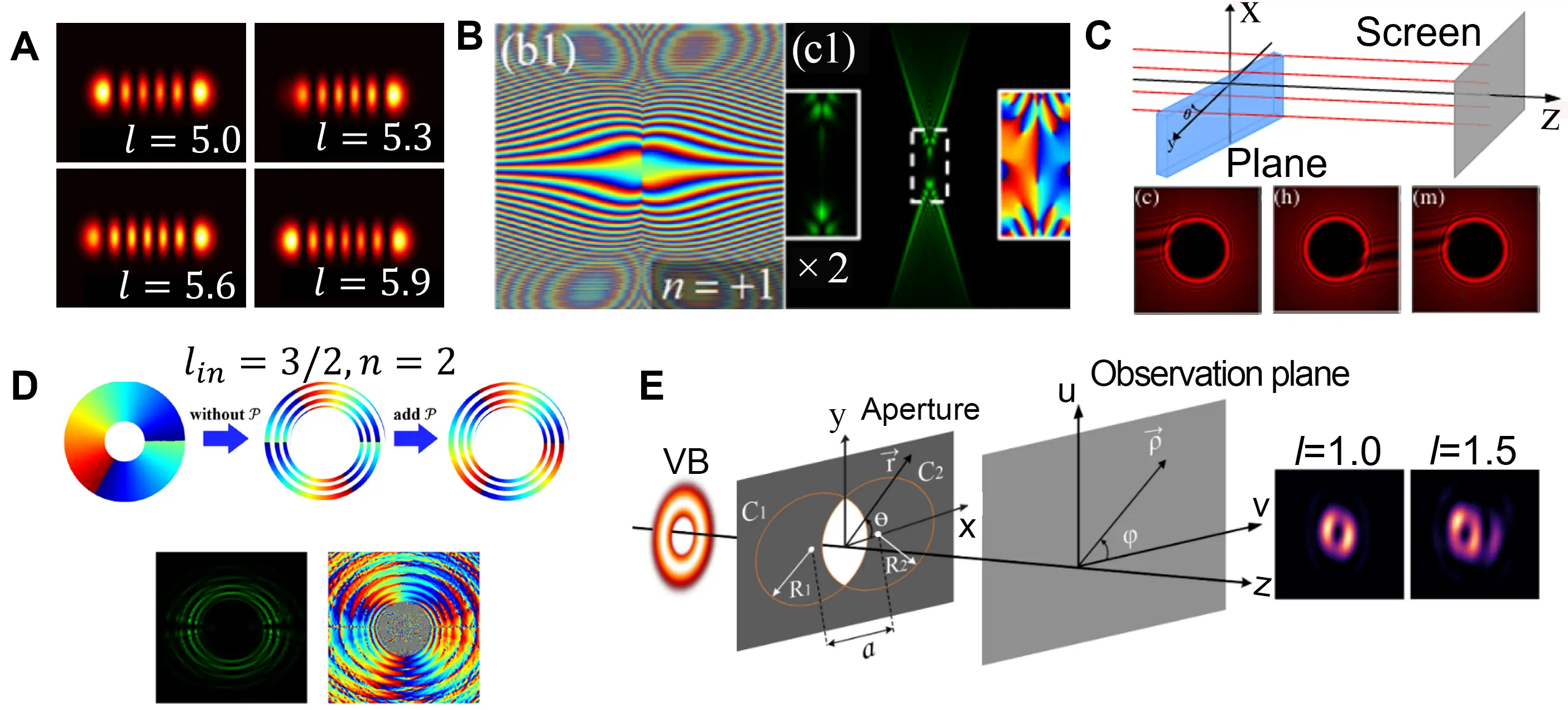

The cylindrical lens is a classic example, and Zhou et al.[128] have confirmed that the Laguerre-Gaussian to Hermite-Gaussian mode interconversion can be used in the recognition of TCs. As shown in Figure 10A, the fractional vortex beam can be converted into a coherent composition of Hermite-Gaussian beam. As the fractional TC gradually increases, it is evident that the birth of a new lobe occurs, and the converted beam will gradually evolve from lm order to lm + 1 order. Based on such a phenomenon, the fractional TC with an interval of 0.1 can be measured based on the simulated results of the new lobe intensity comparison in experiment. More recently, Cui et al.[88] proposed a fractional TC recognition method based on a self-rotating phase mask. The self-rotating phase is shown in Figure 10B and it can be expressed as

Figure 10. Measurement methods based on the diffraction through phase and amplitude masks. (A) The intensities of mode converted fractional vortex beam with vary TCs. Republished with permission from[128]; (B) The rotating beam phase and the intensities of modulated fractional vortex beam at far field. Republished with permission from[88]; (C) Fractional vortex measurement with rotational phase plate and the modulated intensities. Republished with permission from[129]; (D) Integer OAM conversion of fractional vortex beams based on spiral slits and the simulation intensities[87]; (E) The intersecting circular aperture to modulate the fractional vortex beam and resulting intensities[130].

Moreover, using simpler phase components, such as a phase plate, can also measure the TCs of fractional vortices quantitatively. Hosseini-Saber et al.[129] proposed a universal measurement method for multiple models of fractional vortices using phase difference. This method utilizes a phase plate to partially modulate fractional vortices. Figure 10C shows the intensities obtained by rotating the phase plate angle. In this method, θ1, θ2, and θ3 are the angles corresponding to the continuous minimum visibility images, as shown in Figure 10C. Then, the fractional part of the TC value can be calculated as follows:

In addition to phase masks, the binary amplitude mask has been validated in the measurement of fractional TCs[79,131-133]. Mao et al.[87] designed a spiral structure (Figure 10D) to perform a coordinate transformation for fractional vortices, converting a fractional vortex beam (Ein(r,θ)) into integer order OAM modes (Eout(ρ,φ)), which can be written as

4.2 Interferogram analysis.

For integer vortices, their interferograms with plane waves or spherical waves exhibit fork-shaped or rotating fringes. The number of fringes can be used to determine the magnitude of the TC, and the forked and rotating direction of fringes can determine the sign. However, for fractional vortex beams, their interferogram can only be qualitatively analyzed[134], as shown in Figure 11A. By using a spherical wave, the misalignment in interference fringes (Figure 11B) has been pointed out as being able to measure the fractional part of the TC based on the distance between two nearby fringe D and the displacement of the dislocation S, written as μ = S/D[135]. Due to the periodicity of the vortex beam phase, a measurement method based on Mach-Zehnder interferometer was also proposed to generate unsymmetrical petal fields, and the ratio of peak intensities corresponds to the fractional TC, as shown in Figure 11C[136-139].

Figure 11. Measurement method based on the interference and OAM decomposition. (A) The intensities and interferograms of fractional vortex with TCs of 1.5 and 2.5[134]; (B) The TC measurement by the displacement of dislocation and the crosslines of the interferograms. Republished with permission from[135]; (C) The structure of Mach-Zehnder interferometer and the angular crosslines of the interferograms with varying fractional TCs. Republished with permission from[136]; (D) The interferogram and the correlation results of fractional vortex beams. Republished with permission from[140]; (E) The diagram of KK receiver method to measure TCs[90]; (F) The distribution of fiber grating and the modal-decomposition intensities. Republished with permission from[141]; (G) The diagram of non-linear method to measure TCs and the resulting intensity. Republished with permission from[142]. OAM: orbital angular momentum; TC: topological charge; KK: Kramers–Kronig.

Moreover, Shikder et al.[140] proposed an untrained model method based on hybrid digital optical correlation, as shown in Figure 11D. A tilted Gaussian beam interferes with the measured fractional vortex beam, producing interference fringes. The integer part of the TC can be obtained through the fork number. The fractional part is obtained by double autocorrelation using the fork-shaped interference pattern of the nearest integer TC. This method can measure the fractional TC in real-time with a resolution of 0.05 and an accuracy of 98.87%.

4.3 Modal-decomposition

Based on the modal-superposition model of the fractional vortex beam, modal-decomposition becomes an effective way to calculate the fractional TCs[20,90,141-147]. The Kramers–Kronig (KK) receiver is an effective method for direct detection of complex-valued signals, which breaks through the limitation of a single photodetector that can only detect and process the intensity information of optical signals. Lin et al.[90] first introduced the KK receiver to realize a single-shot fractional vortex beam and complex OAM spectral measurement (Figure 11E). In the experiment, a complex OAM beam is coaxially interfered with a Gaussian reference beam, and the interference intensity is recorded. The complex amplitude is solved by the logarithmic Hilbert transform on its angular intensity. Subsequently, the OAM spectrum can be calculated by a Fourier transform. This method does not require phase scanning, mechanical movement, or deep learning, and can extend the measurement dimension to fractional and integer vortex beams of 1-30 order OAM. According to Eq. (12) and Eq. (13), the relationship between the average TC (Mcal) and the OAM spectrum can be written as:

where |Cn(m)| is the weight of each OAM mode. Then, the fractional TC can be optimized by Eq. (28):

Structured phase modulation devices are also effective in fractional vortex measurements. Zhu et al.[141] proposed a finite integer component measurement method that uses a grating to modulate fractional vortex rotation in the far field to generate beams with TCs of -1, 0, and 1, as shown in Figure 11F. By utilizing the energy ratio of two integer TCs (l = 0 and -1), the fractional TC of the beam can be written as:

where

Zhao et al.[142] proposed a nonlinear Dammam grating made of LiNbO3 crystal to achieve the sorting of fractional vortex beams in the near-infrared band (Figure 11G). When the near-infrared fractional vortex beam under test is incident on a designed nonlinear photonic crystal, visible second harmonic diffraction spots with specific patterns will be generated. The fractional TCs are determined with an interval of 0.1 based on the location of the first and last Gaussian like points and a simulation lookup table. Moreover, other novel methods, such as computer-generated hologram[20,147] and meta surface[146], can also be applied in fractional TC measurement.

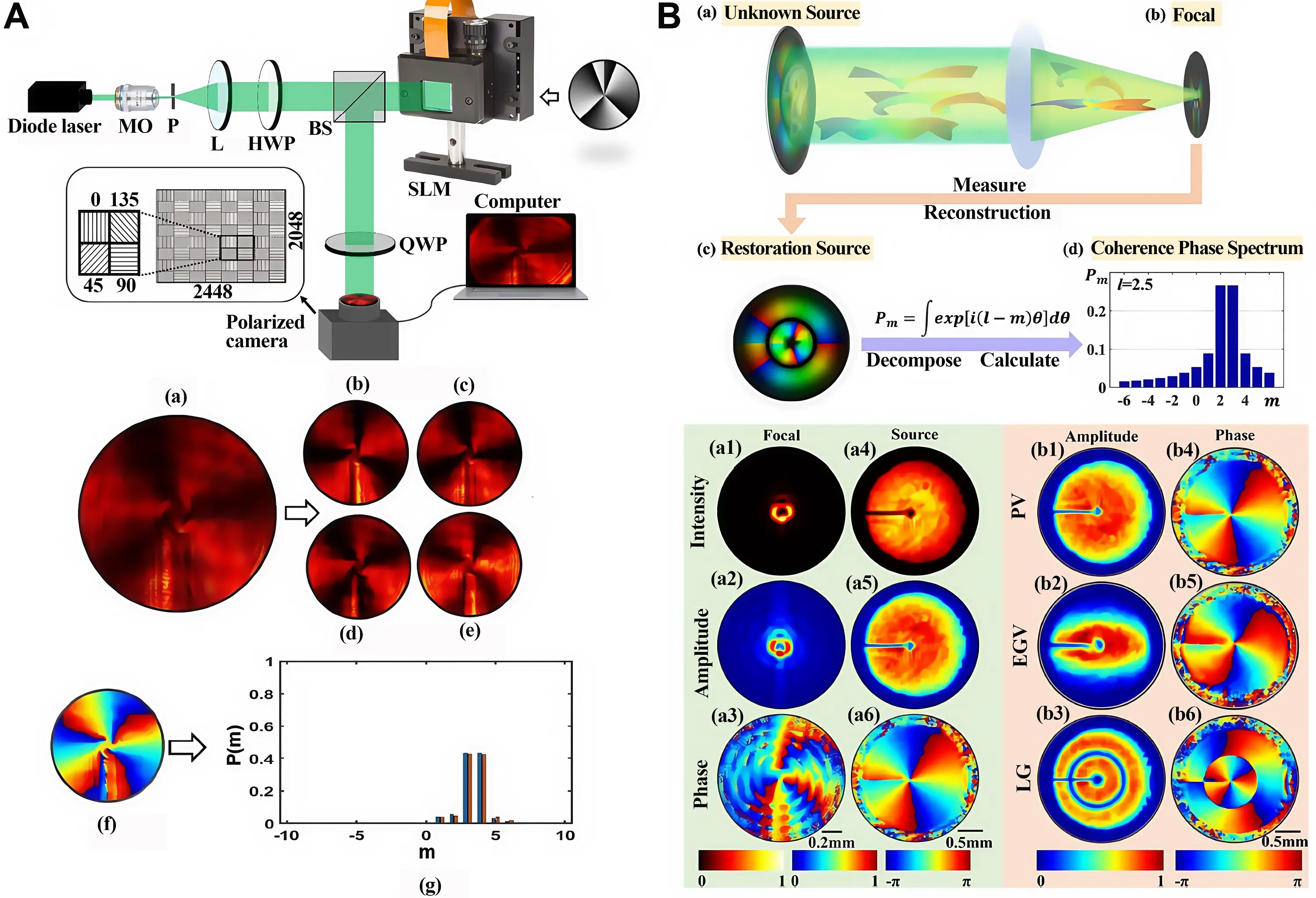

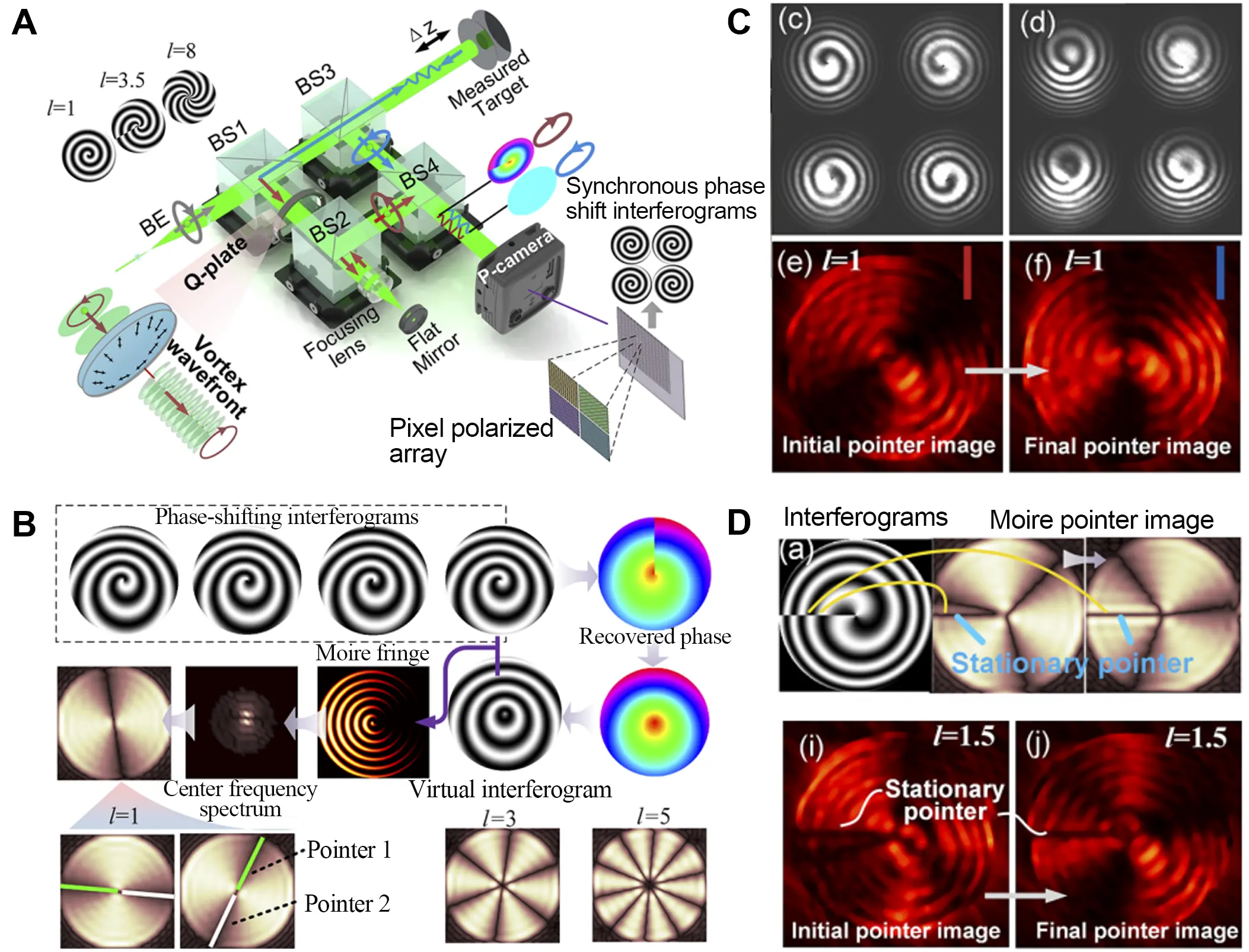

4.4 Light field reconstruction

The TC of a fractional vortex beam can be accurately calculated by measuring the phase term of the optical field on the source plane. Using the four-step phase shifting method and recording the interference intensities I1, I2, I3 and I4 with phase shifts of 0, π/2, π, and 3π/2, the phase term can be calculated by

Figure 12. Light field reconstruction for fractional vortex measurement. (A) Four step phase-shifting measurement method based on polarization manipulation[89]; (B) Phase spectrum decomposition and fractional vortex measurement method based on coherence diffraction imaging algorithm[47]. SLM: spatial light modulator; BS: beam splitter.

To achieve accurate measurement of fractional vortex beams under arbitrary spatial coherence conditions, Wang et al. have proposed a multi-mode diffraction imaging algorithm[47,114]. Using such an algorithm, the light field on the source plane can be retrieved, as shown in Figure 12B. The phase spectrum can be used to measure the fractional TC, which is defined as:

Remarkably, they found that by selecting the two highest peak values of the integer TCs m0 and m1, and their spectrum value

This method can achieve fractional vortex measurement with an accuracy of 0.1 under various degrees of coherence.

4.5 Deep learning

Recently, deep learning has been widely applied in fields such as optical imaging, optical design, and optical parameter measurement. Deep learning based on classification problems can be expressed as Y = fDNN(X), where fDNN represents a neural network model, Y is the label, and X is the feature. Here, the TC recognition can be regarded as a classification problem, and the loss function in training often uses the cross-entropy function which can be written as

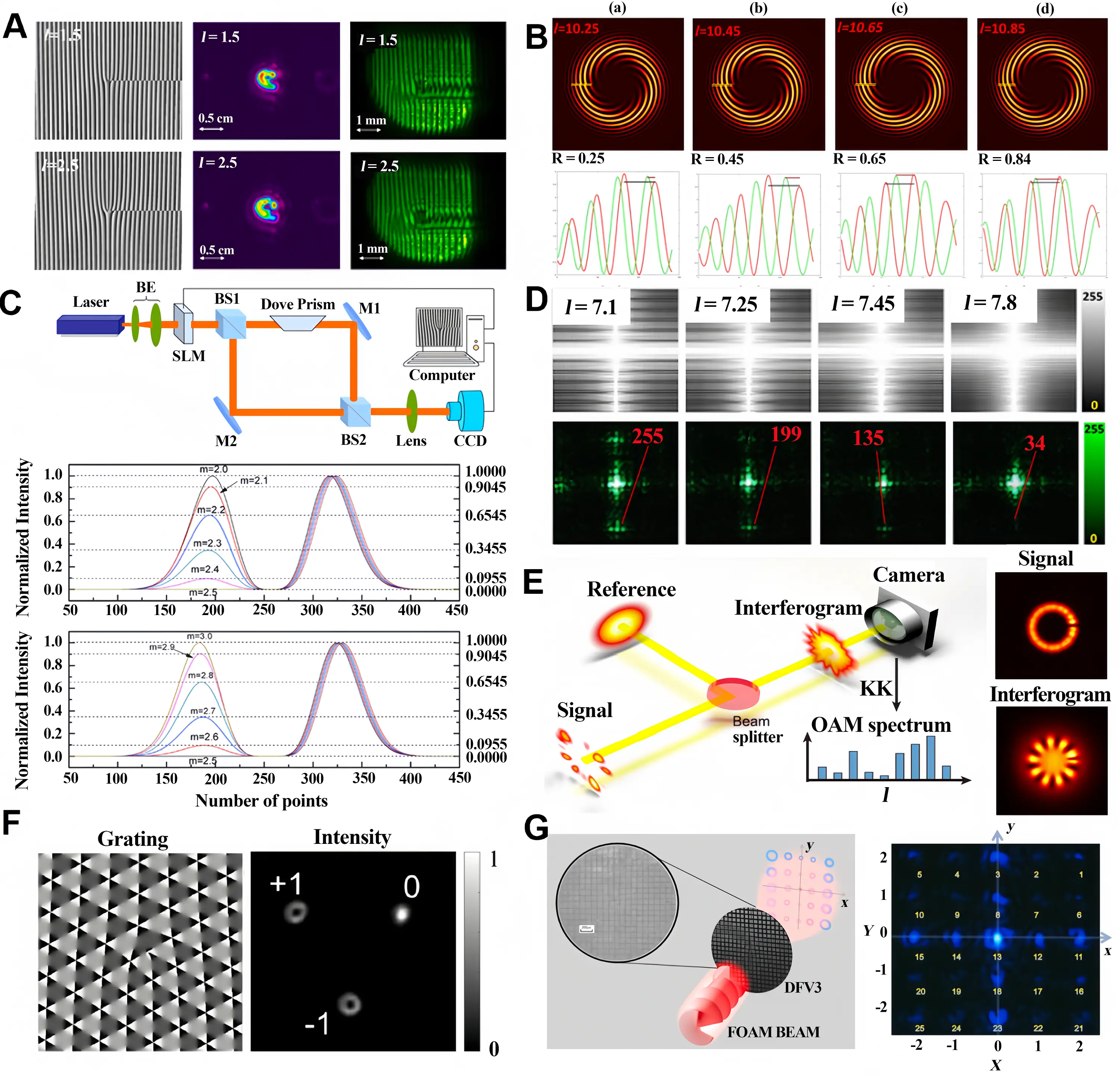

Due to the extremely small differences in the intensity and diffraction patterns of fractional vortex beams with minimal TC differences, it is difficult to directly recognize the TC. To solve this problem, Liu et al.[54] first proposed a scheme for directly recognizing fractional vortex beams. This work adopts the DenseNet framework and achieves high-precision measurement of TC intervals as low as 0.01, as shown in Figure 13A. Moreover, direct recognition is also used for the measurement of large topological fractional vortex beam[149] and other fractional vortex beam models, such as power exponent fractional vortex[150], fractional vortex beam arrays[151], and so on[152].

Figure 13. Learning-based fractional vortex measurement. (A) Deep neural network of learning-based ultrahigh precise fractional vortex beam measurement. Republished with permission from[54]; (B) Flow chart of fractional vortex beam measurement based on speckle recognition after dynamic scattering medium. Republished with permission from[91]; (C) The diffractive neural network used to sort fractional vortex beam with 0.5 interval. Republished with permission from[157]; (D) Measurement device for TCs of fractional vortex optical beams in multimode optical fibers[158]; (E) Intensity and phase of completed and occluded fractional vortex generated in the radio frequency band. Republished with permission from[159]; (F) Acoustic fractional vortex beam measurement process based on deep learning[50].

As shown earlier, the modulated fractional vortices produce a more pronounced structure. By using binary masks[92], computer generated holograms[153-155], and optical elements[156], effective information about fractional vortex phase in the optical field is extracted, making it easier for neural network models to learn the mapping relationship between intensity and TCs. Typically, Feng et al.[91] used dynamic scatterers to modulate fractional vortex optical beams into speckle, as shown in Figure 13B. This method enhanced the accuracy of fractional vortices with a TC interval of 0.01 to 99.83%. Moreover, Shi et al.[92] used amplitude masks to modulate fractional vortex beams, achieving the measurement of fractional vortices with a TC interval of 0.001.

Diffractive neural network is an all-optical computing architecture that directly treats optical diffraction layers as “neurons”. The input light field sequentially passes through multiple layers of diffraction surfaces that have undergone phase, amplitude, or other modulation, completing matrix operations in free space propagation. The modulated beam will finally focus onto the designed region at the plane of the detectors. Recently, Wang et al.[160] used an opt-electronic neural network to realize the OAM spectrum measurement, revealing the potential of diffractive neural networks for measuring fractional vortices. Ren et al.[157] used a diffractive neural network to realize the sorting of fractional vortex beam, as shown in Figure 13C. Such a diffractive neural network can achieve 100% accuracy for the fractional vortex beams with a 0.5 interval.

Deep learning can also accurately measure fractional vortex beams under conditions that are difficult to measure using traditional methods, including low spatial coherence, strong scattering media, and non-optical bands. Wang et al.[48] take the amplitude of the cross-spectral density as input and achieves an accuracy of 99.99% for partially coherent fractional vortex beams with intervals of 0.1, whose intensities have degenerated into a Gaussian distribution. Due to mode crosstalk in fibers, the transmitted vortex beams are difficult to maintain their vortex structure and evolve into speckle patterns. Wang et al.[158] first used a dual arm structure neural network model to achieve TC decomposition and measurement of the coherent superposition of fractional vortex beams, achieving 100% accuracy in double-channel TC measurement, as shown in Figure 13D. Moreover, Tang et al.[161] realized the 32 multiplexed fractional vortex beam recognition using deep learning. In the radio frequency band, Sun et al.[159] used a neural network to achieve the measurement of occluded and down sampling fractional vortices, as shown in Figure 13E. Moreover, Cao et al.[50] used deep neural networks to measure acoustic fractional vortices at low sampling intervals as shown in Figure 13F. This method achieved a minimum TC interval of 0.025 and an accuracy of 95%.

4.6 Other measurement method

In addition to the common diffraction, interferometry and algorithm supported fractional vortex measurement schemes mentioned above, physical phenomena caused by the characteristics of fractional vortex beams themselves, such as rotational Doppler effect[46], interaction with nonlinear materials[162] and so on[163,164], can also be used for the measurement of fractional vortices. Spatial self-phase modulation is an all-optical modulation phenomenon caused by the refractive nonlinearity of materials, which is widely present in 2D layered materials such as graphene, transition metal dihalides, and black phosphorus. Due to its ability to generate novel polarization, phase, and coherence distributions in light beams, this phenomenon is widely used in nonlinear photonic devices such as all-optical switches and all-optical diodes. Spatial self-phase modulation has been found to be useful for measuring integer vortices[165]. In recent years, Ling et al.[162] used spatial self-phase modulation of nonlinear materials to classify semi-integer stage vortex beams. As shown in Figure 14A, the tail size of off-axis integer vortices and semi-integer vortices on the self-diffraction ring is different, which can be used to determine the fractional part of their TCs and the integer part can be obtained based on the complete trailing number.

In addition, the rotational Doppler effect of integer vortices has been studied, which exists in the case of relative rotational motion between the source and the targets. The Doppler frequency shift in scattered light intensity can be written as

Due to the broadening of OAM spectrum in fractional vortex beams, the application of fractional vortices in rotating Doppler velocimetry will result in significant peak broadening and a decrease in signal-to-noise ratio. Based on the above phenomenon, Hu et al.[46] proposed a real-time and quantitative TC measurement of fractional vortex beams using the rotational Doppler effect. As Figure 14B shows, by dynamically loading the compensation vortex phase, the broadened signal gradually disappears, thus determining the fractional part of TC for the target fractional vortices. This method only requires a single pixel photodetector and achieves real-time measurement with 96% accuracy within the range of 4.3-10.3 with an interval of 0.1.

Optical memory effect is a phenomenon that occurs when light passes through scattering media such as ground glass, biological tissue, etc. Specifically, when the angle of incident light varies within a small range, although the light is scattered multiple times by the medium, the speckle intensity formed by the emitted light will shift, but its shape and characteristics remain basically unchanged and highly correlated with the original speckle. Ye et al.[164] proposed the concept of the vortex memory effect. When vortex beams carrying fractional or integer TC pass through strong scattering media, the generated speckle patterns still maintain high correlation even when the TCs undergo small shift. By using correlation calculation, the complete fractional OAM spectrum can be obtained based on a single speckle pattern, as shown in Figure 14C, which holds potential in the measurement of fractional TCs.

In summary, among current methods for measuring fractional TCs, deep learning approaches achieve the highest resolution with a resolvable TC interval of 0.001, limited primarily by sensor resolution. Other techniques, including diffractive mask, interferogram analysis, modal decomposition, optical memory effect, and optical field reconstruction, have reported a minimum resolvable interval of 0.1 or 0.05, constrained by the accuracy of fitting or reconstruction processes. In practical applications such as holographic encryption, a resolution of 0.1 is generally adequate. However, when fractional vortex beams are used in OAM-based optical communications, the ability to resolve smaller intervals can enhance channel capacity and thus improve communication efficiency. More importantly, measurement accuracy cannot exceed generation accuracy. Given the propagation instability exhibited by most fractional vortex beams, discussing measurement precision becomes irrelevant if the light source has been perturbed through propagation or in turbulent media.

5. Applications

Fractional vortex beams possess continuous TCs and phase discontinuities. This characteristic allows them to transcend the discrete modal constraints inherent to integer-order vortex beams. This additional degree of freedom has already delivered decisive advantages across disparate photonic arenas. In optical tweezers, a controllable intensity gap arrests particle motion and enables size-selective sorting[15,18,25-31]. In imaging, fractional spiral-phase filters break rotational symmetry to yield direction-selective edge enhancement and texture-resolved differentiation[39-41]. In rotational Doppler metrology, the intrinsic multi-mode composition of fractional OAM suppresses signal cancellation, allowing robust retrieval of angular velocity and structural periodicity from complex rotating targets[21,44-46]. In free-space and acoustic communication, dense fractional-OAM multiplexing expands channel capacity[51-61]. In holography, ultra-dense topological-charge encoding shrinks vortex-ring footprints and elevates security against reverse engineering[17,62,63]. In displacement sensing, a stationary pointer arising from the fractional phase discontinuity furnishes an absolute zero reference[64,65]. In quantum entanglement, incorporating half-integer spiral phase plates enables high-dimensional OAM entanglement certification with only two detectors, yielding a Clauser-Horne-Shimony-Holt-Bell violation that surpasses the two-qubit limit[66,67]. In nonlinear interactions, fractional vortex beams exhibit anomalous nonlinear robustness: their multimodal skeleton suppresses thermal blooming, supporting nonlocal quasi-solitons with tunable OAM and transverse drift[42,68,166,167].

5.1 Optical tweezers

Vortex beams exhibit a characteristic annular intensity profile and a helical phase gradient. Upon interaction with microparticles, the annular intensity generates a radial gradient force, while the helical phase produces an azimuthal force. For a small sphere of radius α, the intensity-gradient force has the form[18]:

where k is the light’s wave number; Cn is a constant related to the refractive indices of the particles and the liquid medium;

where v is the frequency of light; I0 is a coefficient proportional to the optical power density;

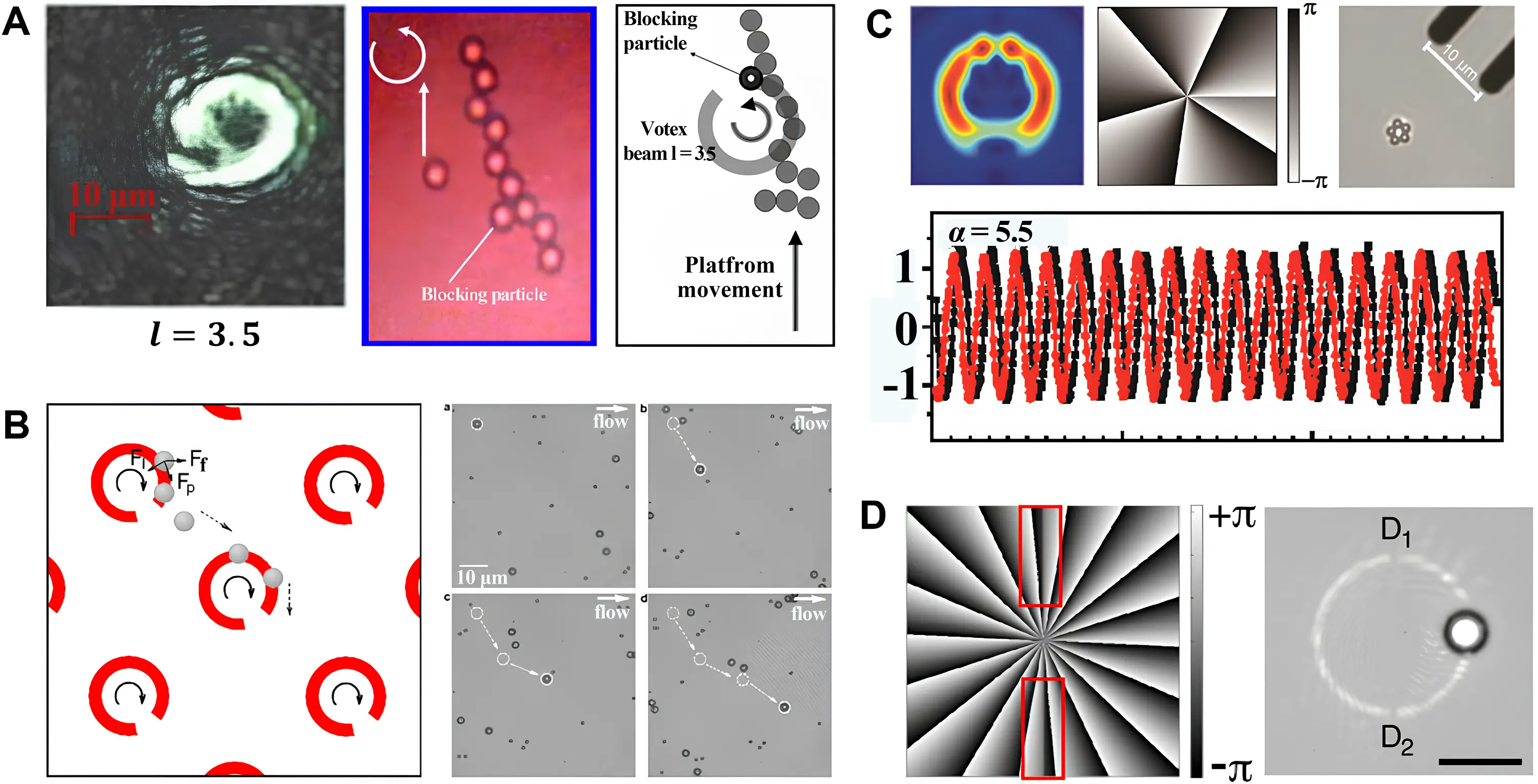

In contrast, fractional vortex beams demonstrate more complex behavior. Their intensity profile features a low-intensity gap, accompanied by a phase discontinuity at this location. This results in a significant reduction in optical forces near the gap, facilitating more sophisticated manipulation schemes. The pioneering work employing fractional vortex beams for optical trapping was reported by Tao et al.[30]. Their study quantitatively analyzed optical forces on particles exerted by fractional vortex beams. Leveraging the inherent property of the gap to arrest particle motion, they designed a system for guiding and aligning particle transport. The left panel of Figure 15A illustrates the intensity of a fractional vortex beam with a TC of 3.5, while the middle and right panels present the corresponding experimental results and schematic diagram, respectively. Due to the presence of a notch in the fractional vortex, particles cease rotational motion at the notch and escape the optical confinement, resulting in alignment and transport effects.

Figure 15. Optical tweezers. (A) Patterns of the vortex beams and experimental result for aligning and transporting particles with fractional vortex beam (l represents TC)[30]; (B) Optical sorting manipulated by fractional vortex array, generated by a phase-only Talbot array illuminator. Republished with permission from[18]; (C) Precise measurement of trapping and manipulation properties of focused fractional vortex beams (α represents TC). Republished with permission from[31]; (D) Optical tweezers with perfect fractional vortex beam[15]. TC: topological charge.

To further expand fractional vortex beam applications in optical trapping, Guo et al. implemented a phase-only Talbot array illuminator to generate an array of optical vortices with fractional TCs[18]. As shown in Figure 15B, the left panel depicts a fractional vortex array, while the right panel shows sequential snapshots of the particles’ motion. The core principle exploits the size-dependent optical forces of fractional vortex beams: larger microparticles experience sufficient force from the fractional vortex to alter their trajectory, whereas smaller particles remain unaffected and propagate linearly. This work transformed its solitary intensity notch into a symmetric constellation of low-contrast gaps and held significant promise for biological cell sorting applications.

Studies on focused fractional vortex beams revealed distinct force characteristics on particles. By tailoring the azimuthal phase profile of a focused fractional vortex, Gao et al. realized optical trapping and manipulation of microparticles and microorganisms with fractional vortex beams at the focal plane. As shown in Figure 15C, the top row displays, from left to right, the intensity distribution of a fractional vortex beam at the focal plane, the initial phase of a fractional vortex beam with a TC of 5.5, and a typical snapshot of five microparticles trapped by the fractional vortex beam optical lattice. The bottom row presents the temporal evolution of the x(t) and y(t) coordinates for one of the trapped microparticles. Compared with a standard fractional vortex beam, a focused fractional vortex beam exhibits a more uniform intensity profile. When the number of captured microparticles is suitable to form a particle necklace, stable rotation within a focused fractional vortex beam can be achieved[31].

Furthermore, introducing additional phase dislocations can homogenize the intensity distribution of fractional vortex beams, enhancing their trapping performance to approach that of integer-order vortices. As illustrated in Figure 15D, the left panel depicts the phase distribution of a perfect fractional vortex beam with a TC of 2, featuring two phase dislocations (highlighted by the red line). The right panel shows a typical microscopic image of a bead trapped within the corresponding perfect fractional vortex ring. This provides an additional degree of freedom for optical manipulation with fractional vortex beams[15].

5.2 Tunable edge enhancement imaging

In the field of optical imaging, vortex beams have been extensively utilized for image processing and edge enhancement[32,33]. The spiral phase filtering process achieves this by placing a spiral phase plate in the focal plane of a 4f system. This configuration results in a detected electric field signal that constitutes the convolution of the source image with the Fourier transform of the vortex phase, which can be given as[35]:

where O(x,y) denotes the complex transmission function of the sample;

where Ein is the complex amplitude of the input field, Eout is that of the output field, and ψin is the phase of the input light field. Consequently, the resulting intensity distribution incorporates spatial derivatives of the position coordinates, thereby generating the edge enhancement effect. Owing to their azimuthal symmetry, integer-order vortices produce uniform edge enhancement across all orientations during spiral phase filtering[34,35].

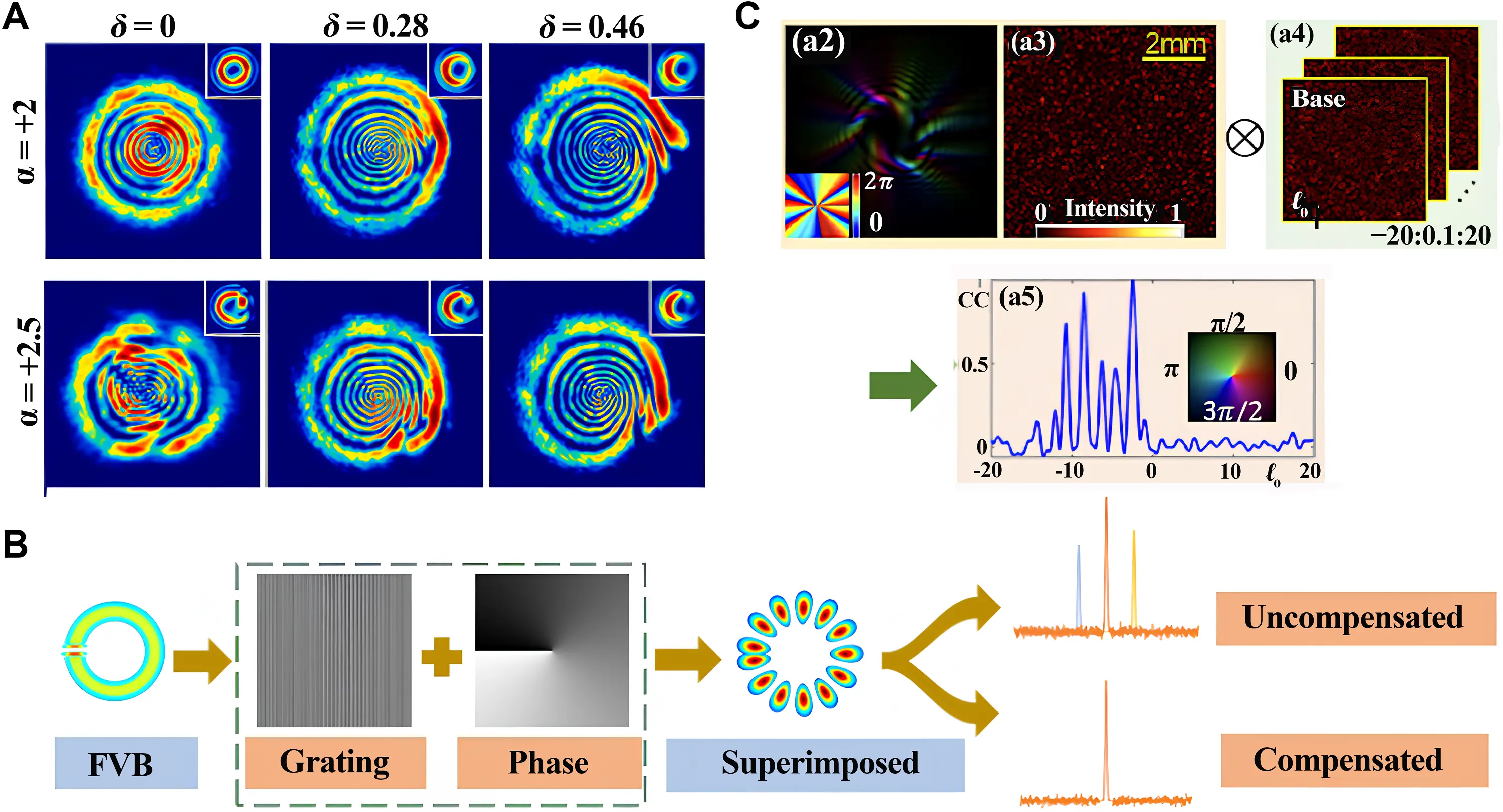

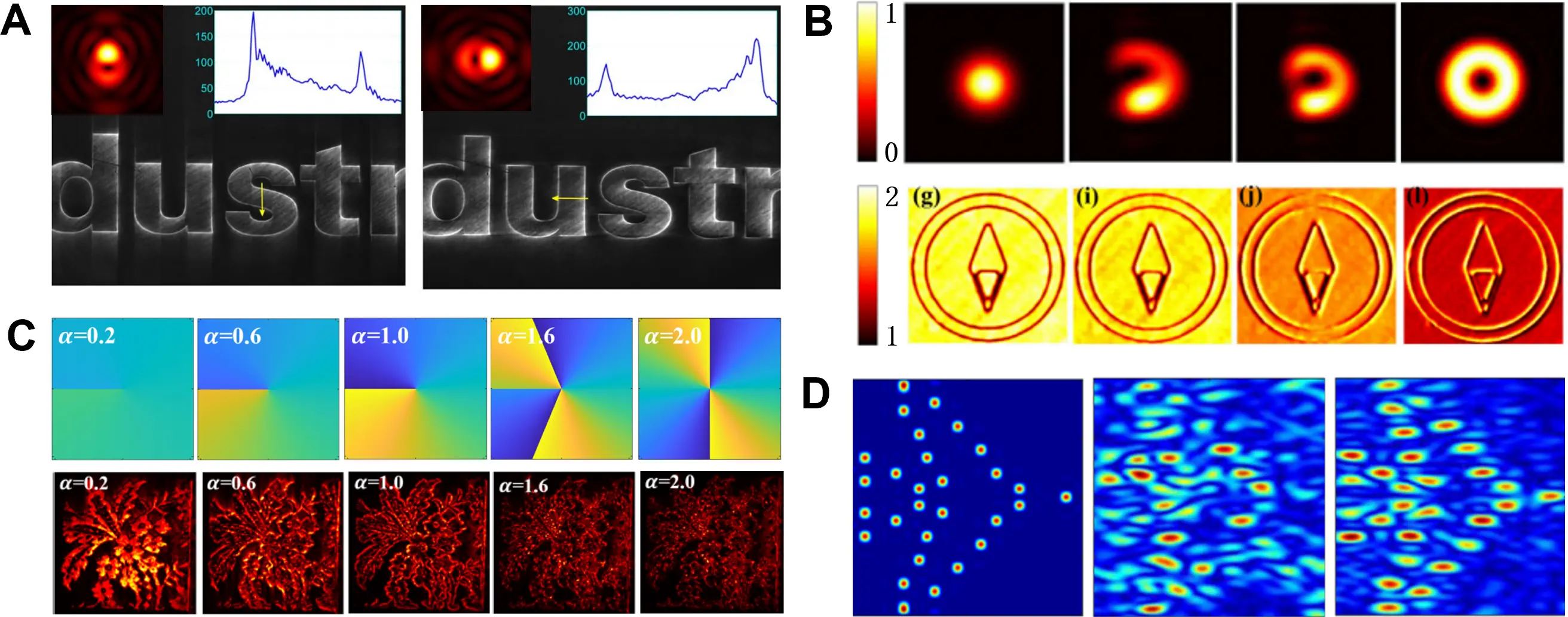

In contrast, fractional vortex beams exhibit phase discontinuities which disrupt the inherent symmetry of the spiral phase filtering process. As a result, fractional-order spiral phase filtering selectively enhances edges along specific directions. In 2009, Situ et al. demonstrated that replacing an integer spiral phase plate with a fractional one inside a 4f correlator breaks the radial symmetry of the filter, yielding anisotropic edge enhancement[36]. As shown in Figure 16A, the left and right panels demonstrate the resulting edge enhancement when the fractional spiral phase plate is rotated by angles of π and π/2. The asymmetric phase discontinuity selectively suppresses the zero-frequency component, allowing directional phase gradients to be highlighted.

Figure 16. Tunable edge enhancement imaging. (A) Orientation-selective edge detection of a transparent object “dustr” based on a fractional vortex beam. Republished with permission from[36]; (B) Edge-enhanced imaging with different fractional spiral phase filters[37]; (C) Fractional topological spatial differentiation (α denotes fractional TC). Republished with permission from[11]; (D) Electromagnetic vortex enhanced imaging using fractional OAM beams. Republished with permission from[38]. TC: topological charge.

Building on this concept, Wang et al. transferred the fractional spiral phase filter to a lensless ghost-imaging architecture driven by pseudo-thermal light[37]. By continuously tuning the TC from 0 to 1, they observed a monotonic increase in edge brightness. As shown in Figure 16B, the top row shows the intensity distributions of fractional vortex beams with TCs of 0, 0.3, 0.7, and 1, respectively. The bottom row displays the corresponding edge-enhanced imaging results obtained using a fractional spiral phase filter with TCs of 0, 0.4, 0.6, and 1. A notable transition occurs at a TC of 0.5. For values below this threshold, the beam lacks a vortex core and exhibits weak enhancement; in contrast, values above it generate a fully developed vortex form with pronounced contrast.

The notion of fractional calculus was recently imported into optical analog computing by Yan et al.[11]. They introduced a Fourier-space filter whose transfer function exhibits both a specific power amplitude and a spiral phase with fractional TC. The resulting point-spread function is inherently non-local and asymmetric for non-integer TCs, producing relief-like images that preserve low-to-mid frequency textures, while an integer TC recovers the familiar symmetric edge maps. As shown in Figure 16C, the first row displays the phase profiles of the transfer functions for different differential orders. The bottom row presents the experimental results of fractional topological spatial differentiation applied to a patterned texture image. When the differential order is less than 1, the output exhibits relief-like enhancement, preserving texture features, while suppressing high-frequency noise in the background. In contrast, when the differential order is 1, the output removes texture details that represent low- and medium-frequency information, retaining image edges and high-frequency noise. Fractional differentiation across different intervals offers unique advantages, allowing the selection of appropriate orders to meet diverse imaging requirements. For relief-like imaging and texture enhancement, lower orders are preferred, while integer orders are ideal for high-frequency detail extraction.

Single-pixel wavefront imaging reconstructs both amplitude and phase using structured illumination and a bucket detector. Conventional schemes utilize integer orbital angular momentum modes as a complex-valued basis. However, the discrete nature of their TCs inherently limits the number of orthogonal patterns, which consequently restricts the attainable field of view. Yin et al. implemented fractional Laguerre–Gaussian modes with non-integer azimuthal indices, generating a quasi-continuous basis set[38]. By finely stepping the fractional index, the basis cardinality is increased several-fold without enlarging the radial or azimuthal ranges, thereby enlarging the field of view and improving spatial resolution. Systematic simulations and experiments revealed a linear relationship between the maximum spot radius of the fractional Laguerre–Gaussian basis and the reconstructed field of view. Unlike integer-order OAM beams, fractional vortex bases lack strict orthogonality. However, the image reconstruction in this work does not rely on this property. Instead, it leverages a compressed sensing framework, specifically the TVAL3 algorithm, which exhibits a notable tolerance to the errors introduced by non-orthogonality. Importantly, this method retains high-fidelity reconstructions at sampling ratios as low as 15%, outperforming Hadamard-basis single-pixel wavefront imaging that suffers from pronounced pixelation artifacts. These advantages provide a promising modality for rapid, high-resolution wavefront metrology.

Fractional order vortices also show potential applications in two-dimensional radar imaging. The discrete azimuthal coordinate φ and the OAM index form a Fourier pair, and leveraging fractional-order vortices allows the radar to sample the OAM index at markedly finer intervals, thereby achieving a substantially enhanced azimuthal resolution[168,169]. As shown in Figure 16D, the ground-truth image is shown in the first panel. The second and third panels show the corresponding two-dimensional imaging results acquired with OAM sampling intervals of 1 and 0.2, respectively. Results show that, compared to the conventional electromagnetic vortex imaging method, the proposed method based on fractional OAM beams can reconstruct the imaging more accurately in noisy environments. By transmitting vortex electromagnetic waves with half-integer OAM via a uniform circular array, Liang et al. exploit the distinct elevation-dependent magnitudes of fractional Bessel functions to decode target elevation. Combined with azimuth reconstruction from integer-order OAM modes, this two-step scheme achieves noise-robust 3-D radar imaging without relative motion, surpassing 180° aliasing limits and enhancing resolution under low signal-to-noise ratio conditions[170].

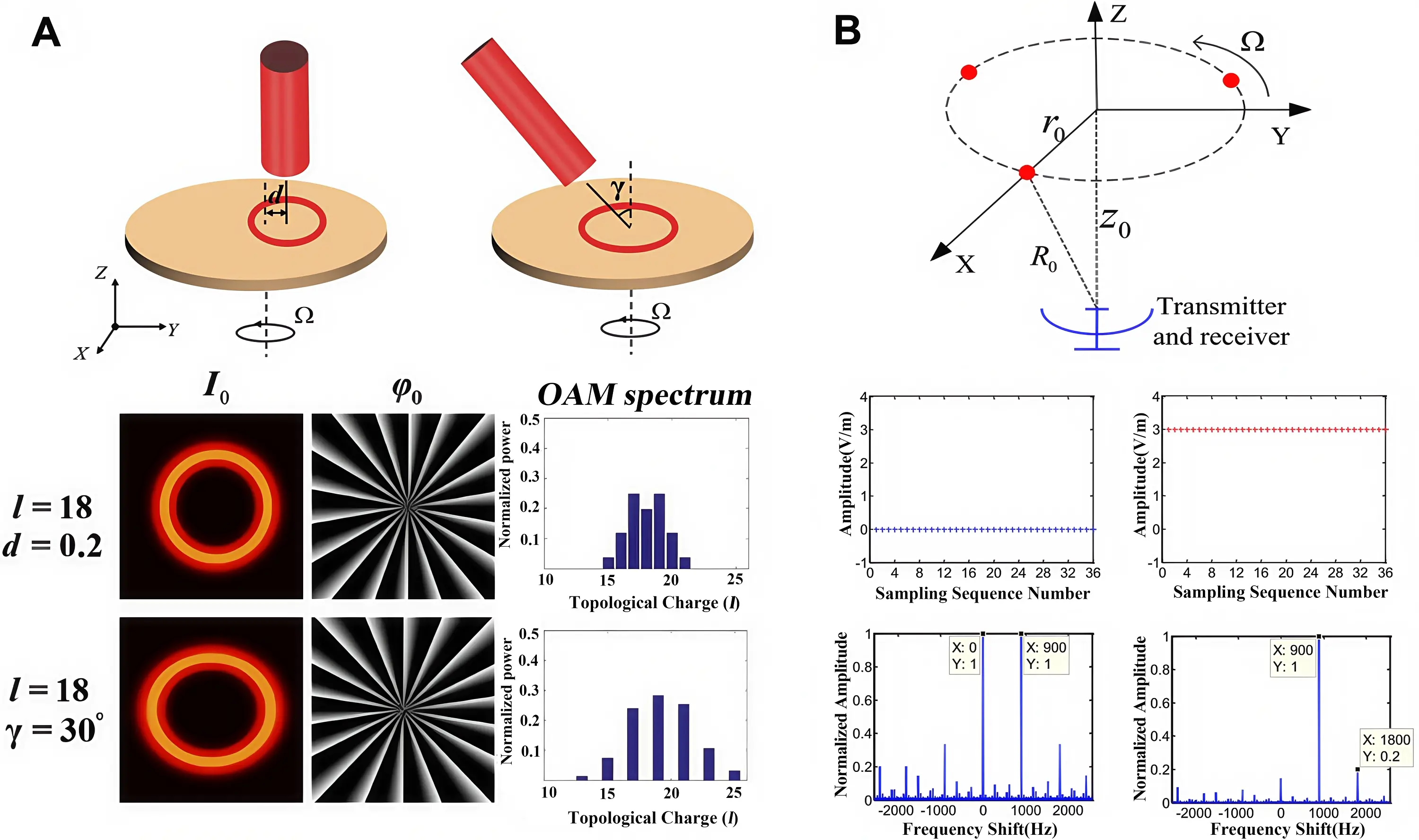

5.3 Rotating velocimetry

It is well-known that a particularly fascinating phenomenon arises when vortex beams carrying OAM are incident perpendicularly onto a rotating surface: the scattered waves exhibit a rotational Doppler effect[44,171]. This effect has garnered significant interest in recent years due to its ability to determine a rotating object’s angular velocity from the generated spectrum. As shown in Figure 17A, initial research revealed that even a single-integer OAM beam can produce a broadened rotational Doppler frequency spectrum under conditions of transverse displacement or angular tilt relative to the rotating object[21]. For lateral displacement, the OAM spectrum distributes symmetrically around the initial TC, with a difference of 1 between the TCs of adjacent modes. For angular deflection, the difference in TCs between adjacent modes becomes 2, and the symmetry of the intensity distribution disappears. It can be explained theoretically: the intensity distribution and phase structure of the light spot on the object are still circular with a lateral displacement, while they become elliptic under angular deflection. The OAM comes from the helical harmonic, and different phase structures have different symmetries. This observation led to the proposal of an OAM modal decomposition method for misaligned optical rotational Doppler velocimetry.

Figure 17. Rotating velocimetry. Broadened OAM spectrum with (A) misaligned Laguerre-Gaussian vortices. Republished with permission from[21] and fractional vortex beams. Republished with permission from[45]. The frequency difference between the highest spectral peaks can be used in rotating velocimetry. OAM: orbital angular momentum.

Extending this integer OAM decomposition principle to fractional OAM beams reveals that their multi-peak rotational Doppler spectra similarly originate from inherent modal superposition. A fractional vortex illumination intrinsically comprises an infinite series of integer-order OAM modes, written as Eq. (12)[45]. It can be found that the integer modes closest to the fractional TC exhibit the highest weighting. Consequently, each integer component interacts with the rotating target to produce its corresponding frequency shift, yielding a spectrum with multi-peaks whose intensities correlate with their respective modal weights. This principle offers distinct advantages when measuring rotating targets with periodic scattering centers, such as anemometers, rotating machinery, or drone propellers, as demonstrated in Figure 17B[45]. Theoretically, as shown in the upper and middle parts of Figure 17B, when an integer-order vortex beam illuminates a three-point spinning system, the system’s symmetry dictates that only echoes corresponding to modes whose TC is an integer multiple of 3, possess non-zero amplitude. Echoes from other modes are negligible. In contrast, a fractional vortex beam inherently decomposes into multiple integer OAM modes, preventing signal cancellation. As shown in the bottom part of Figure 17B, employing a fractional vortex beam (e.g., 1.5 and 3.5) yields echo spectra with pronounced spectral peaks. Analysis of these peak characteristics enables the extraction of the target’s structural periodicity. Furthermore, the rotational speed Ω can be determined from the frequency difference between the highest spectral peaks. The frequency difference fd between the two highest spectral lines is 3Ω/2π. The rotational angular velocity is calculated as Ω = 900 * 2π/3 = 300 * 2π rad/s. In support of this velocity measurement principle based on the fractional-order rotational Doppler effect, Hu et al. also demonstrate that the peak spacing within the fractional-order rotational Doppler spectrum correlates directly with the object’s rotational speed[46].

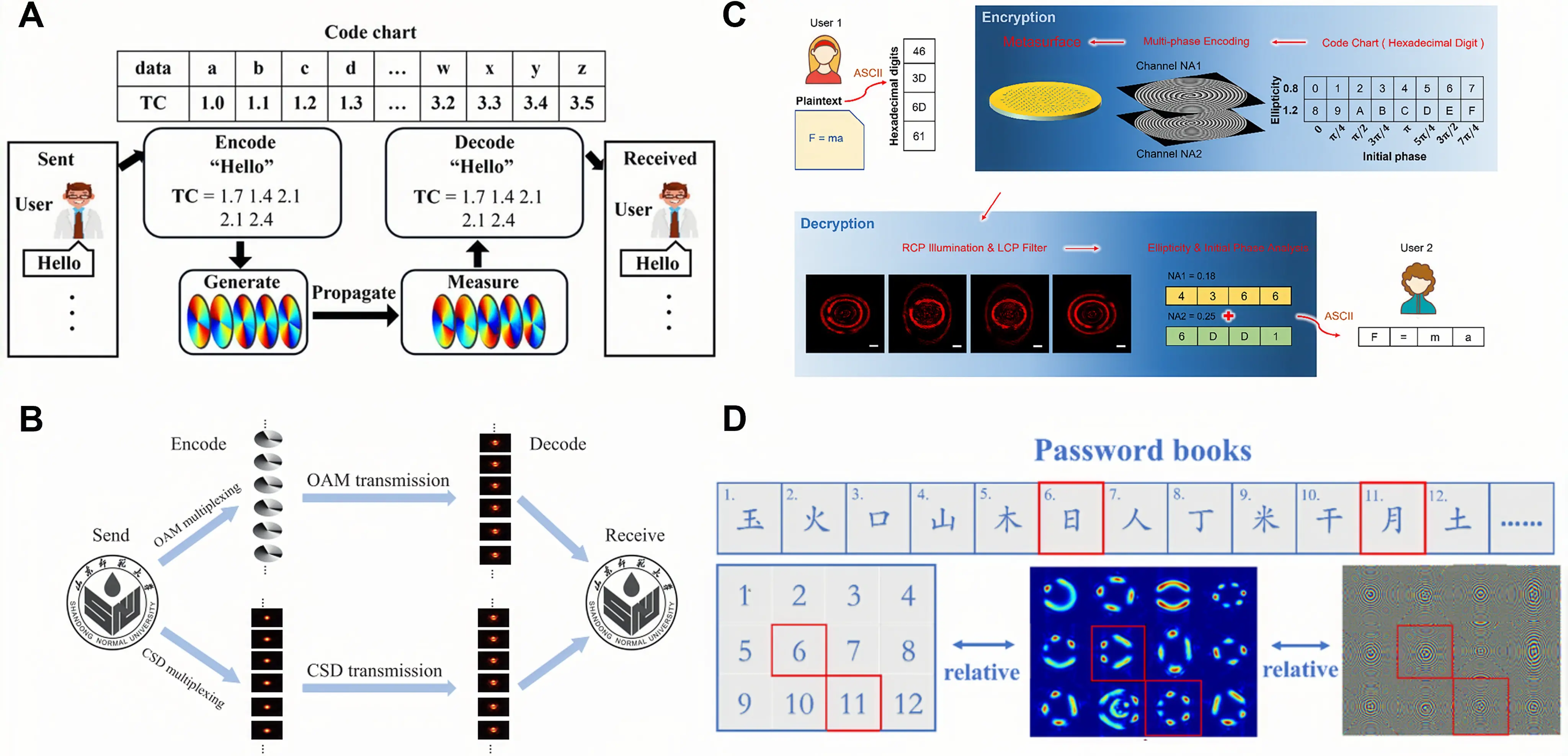

5.4 Optical encryption

Fractional vortex beams, due to their continuously tunable TCs and unique phase structure, have also opened up a pioneering high-capacity channel for the field of optical encryption. Traditional integer-order optical vortex beams are restricted by the discreteness of their modes and the divergence effect, making it difficult to achieve high-density encoding. In contrast, fractional-order modes enable infinite channel expansion through continuous TC intervals. Wang et al. demonstrated high-precision measurement (accuracy better than 0.1) of the TC for various partially coherent fractional vortex beams[47], and successfully validated the feasibility of using these beams for transmitting information encoded within the English alphabet, as shown in Figure 18A. Building upon this progress, a recent study further introduced a deep learning framework based on DenseNet[48]. This approach achieved high-resolution TC identification for low-coherence fractional OAM modes and reduced the OAM mode recognition interval to an impressive 0.01. Within a simulated free-space optical communication system, this method facilitated near-perfect (approaching 100% accuracy) transmission of grayscale images using cross-spectral density multiplexing encoding, as shown in Figure 18B. This deep learning strategy significantly enhanced the stability of TC recognition in low-coherence scenarios, thereby bolstering the anti-interference capability of optical encryption systems in complex environments.

Figure 18. Optical encryption. (A) Optical encoding scheme using fractional vortex beams[47]; (B) Detailed process of transmitting a SDNU logo portrait utilizing free-space optical transmision system with OAM multiplexing and cross-spectral density multiplexing[48]; (C) Proof-of-concept experimental demonstration of optical encryption with perfect fractional vortex beams. Republished with permission from[49]; (D) A passwords book whose core function is to establish a standardized mapping relationship between Chinese character radicals and polarization-encoded fractional perfect composite vortex beams[50]. SDNU: Shandong Normal University; OAM: orbital angular momentum.

Addressing the challenges of bulky size and low integration in traditional optical encryption systems, Zhao et al. achieved flexible control of broadband fractional perfect optical vortex beams in the visible spectrum with a single-plasmonic metasurface[49], as shown in Figure 18C. First, User 1 converts the plaintext message to be transmitted into four double-digit hexadecimal numbers according to the ASCII encoding rule. Subsequently, the multidimensional degrees of freedom of fractional perfect optical vortex beams (ellipticity ε, initial phase φ0, numerical aperture NA) are utilized for encoding, and sixteen hexadecimal digit code tables (covering 0-F) are constructed by combining two ellipticity values with eight initial phase values. Two numerical aperture values are used to distinguish spatially multiplexed channels, corresponding to the first and second digits of the double-digit hexadecimal numbers, respectively. Finally, the encoding parameters are integrated into a single plasmonic metasurface array to form the ciphertext. User 2 illuminates the metasurface array with right-handed circularly polarized light and captures the transmitted fractional perfect optical vortex beams array image (containing four groups of double-ring structures) through a left-handed circularly polarized filter. Based on the preset code table, the ellipticity and opening gap angle of the fractional perfect optical vortex beams are analyzed to restore the double-digit hexadecimal numbers. The original plaintext F = ma is finally recovered via ASCII decoding. This platform enables independent manipulation of beam parameters such as radius and ellipticity. More importantly, by encoding two-digit hexadecimal numbers using fractional perfect optical vortex states, the encryption system is miniaturized to the millimeter scale. This approach effectively resolved aberration issues typically introduced by cascaded optical components, presenting a novel paradigm for developing compact optical encryption devices[49].

On this basis, Wang et al. proposed a scheme for the generation and regulation of fractional perfect composite vortex beams based on a double-layer metasurface[50]. They designed the metasurface structure by combining the Jones matrix formalism with optimized the geometric parameters of nanopillars through a machine learning algorithm, achieving high polarization switching efficiency (with a polarization conversion efficiency of 99.65%). The generated fractional perfect composite vortex beams exhibit petal-like intensity distributions co-regulated by TC, ellipticity, and initial phases. Additionally, grafted fractional perfect composite vortex beams can be constructed via step functions, and independent on-off control and shaping of the inner and outer rings of double-ring fractional perfect composite vortex beams can be realized by means of tuning factors. As shown in Figure 18D, inspired by the hierarchical structure of Chinese character radicals, they mapped semantic radicals to polarization-encoded fractional perfect composite vortex beams, constructing a high-security optical encryption system, which provides a new path for the application of fractional vortex beams in fields such as optical information security and photonic communication.

5.5 OAM multiplexing holography

In recent years, OAM multiplexing holography has exhibited significant advantages such as large capacity and high security, leveraging the degrees of freedom in information loading, characterized by the large number of mutually orthogonal modes inherent in OAM. In digital holography, the field on the hologram plane and the field on the image plane form a Fourier pair. By superimposing the spiral phase structure used for encoding onto the hologram, an angular momentum-preserving hologram is formed. At this point, the selected optical field obtained when the input light strikes the hologram and propagates can be expressed as:

where H and Ein represent the complex amplitudes of the stored hologram and the incident light beam, respectively, and Ematch represents the matching field. The operator “*” denotes convolution, me is the TC of the matching field phase, and md is the TC of the incident beam. It can be seen from the formula that when md = - me, each sampling point follows a Gaussian distribution. However, traditional OAM holography faces bottlenecks in terms of security and display resolution. For instance, the vortex ring sizes corresponding to different TCs vary significantly, making information vulnerable to reverse inference. Meanwhile, the vortex ring size grows drastically with increasing TCs. To avoid crosstalk, the sampling interval must be enlarged based on the maximum ring size, which in turn leads to a decrease in the display resolution of reconstructed images.