Abstract

The Hippocratic Oath enshrines the ethical imperative primum non nocere -“first, do no harm”- thereby guiding medicine practice toward the meticulous avoidance of interventions that may compromise patients’ physiological integrity and overall well-being. Following this principle, benzodiazepines were initially introduced as safer alternatives to barbiturates and have since become one of the most commonly prescribed drug classes for the long-term management of neuropsychiatric disorders in older adults with progressive health deterioration. However, emerging evidence implicates the endogenous benzodiazepine-like peptide, acyl-CoA binding protein/diazepam-binding inhibitor, in the orchestration of maladaptive stress responses. These responses are associated with accelerated pathological aging and increased risks of a spectrum of age-associated morbidities, including metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular diseases, cancers, and immune dysfunction. Corroborating these mechanistic insights, retrospective observational studies have consistently reported significant correlations between long-term benzodiazepine use and elevated risks of cardiovascular mortality, dementia, cancer incidence, impaired responsiveness to immunotherapy, and heightened vulnerability to severe infections. Given these converging lines of evidence, we strongly advocate for the cautious reduction of benzodiazepine prescriptions in elderly patients. Whenever clinically feasible, these agents should be replaced by alternative psychotropic compounds with more favorable risk-benefit profiles, in alignment with contemporary standards of geriatric pharmacotherapy and the ethical imperative to minimize iatrogenic harm.

Keywords

1. Introduction

As global populations continue to age, the medical community increasingly faces the challenge of addressing complex health needs of elderly individuals, who frequently present with multimorbidity, polypharmacy, and heightened physiological vulnerability[1,2]. In this geriatric context, the ethical and clinical imperative primum non nocere—first, do no harm—gains growing significance. The Hippocratic principle serves not only as a moral compass but also as a practical guideline for individualized, risk-averse therapeutic decision-making in older patients.

Aging is accompanied by substantial changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, including reduced hepatic and renal clearance, altered body composition, and increased central nervous system sensitivity[3-5]. These physiological shifts increase the risks of adverse drug reactions, drug-drug interactions, and iatrogenic complications. Consequently, the inappropriate or prolonged pharmacotherapy in geriatric populations can unintentionally precipitate functional decline, cognitive impairment, falls, hospitalizations, and even increased mortality[6-8].

In light of these considerations, the rationalization of pharmacological regimens in older patients has become a cornerstone of geriatric medicine. Clinical frameworks such as the Beers Criteria[9] and STOPP/START guidelines[10] have been developed to identify potentially inappropriate medications (PIM) and to guide clinicians toward safer therapeutic alternatives. Despite these tools and growing awareness, PIM use remains prevalent, often driven by prescribing inertia, under-recognition of drug-related harms, and the paucity of age-specific evidence from clinical trials.

To minimize iatrogenic risk is particularly urgent in managing neuropsychiatric symptoms in the elderly, where the boundary between therapeutic benefit and harm is often precariously narrow[11]. Sedative, anticholinergic, and psychoactive agents—commonly employed to treat anxiety, insomnia, or behavioral disturbances—impose a disproportionately high burden of adverse outcomes in this population[12,13]. A shift toward evidence-based deprescribing and, when possible, the prioritization of non-pharmacological or lower-risk interventions is thus essential to align medical practice with the principles of geriatric care and ethical responsibility[14,15].

In the following sections, we focus on benzodiazepines, a specific class of medications that epitomizes the tension between symptomatic relief and long-term harm in aging patients. We examine their mechanistic implications, epidemiological associations with age-related diseases, and the emerging biological pathways through which they may accelerate pathological aging.

2. Endozepine, an Endogenous Benzodiazepine Equivalent with Pro-Aging Properties

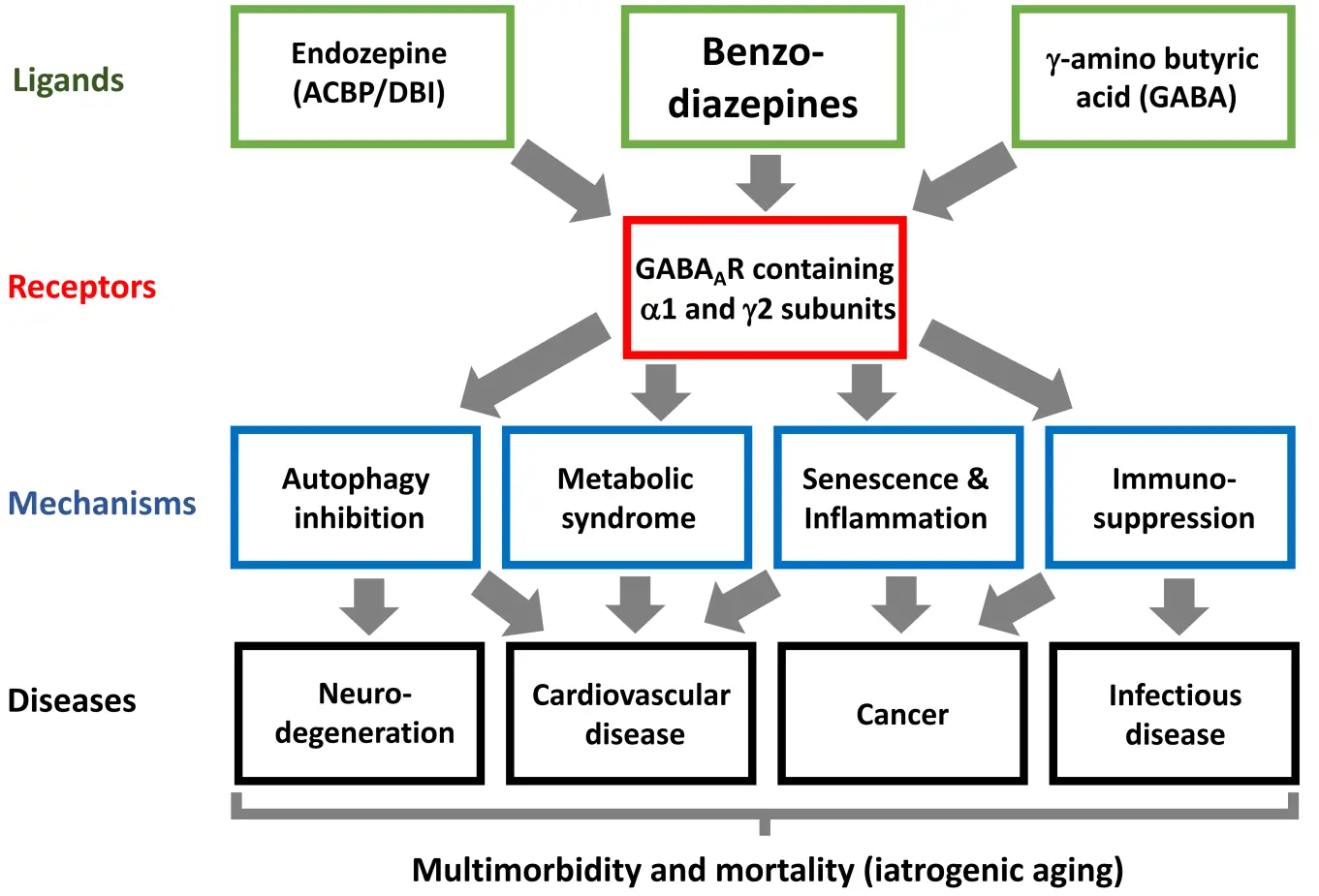

Benzodiazepines may be considered as pharmacological mimetics of endozepine (a contraction of ‘endogenous benzodiazepine’), a protein commonly referred to as diazepam binding inhibitor (DBI) because it displaces the prototypic benzodiazepine diazepam from its receptor, the gamma-amino butyric acid type A receptor (GABAAR)[16-19]. Notably, GABAAR is pentameric, typically composed of two alpha subunits, one beta subunit and two gamma subunits, along with auxiliary subunits. For each of these subunits, several subunits exist, meaning that GABAAR are present in multiple variations that are expressed in a cell type-specific manner[20]. Only GABAAR receptors containing the alpha1 and gamma2 isoforms can bind benzodiazepines and endozepine[21]. Both benzodiazepines and endozepine act as positive allosteric modulators, not as direct agonists, to sensitize GABAAR receptors to their agonist GABA, hence enhancing GABA-elicited chloride fluxes (and to a lesser extent bicarbonate fluxes) on the plasma membrane[22,23] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mechanistic link between benzodiazepine use and the enhanced incidence of several major age-related disease. Benzodiazepines act on a subset of GABAAR that also respond to the endozepine ACBP/DBI. Through this action, benzodiazepines affect a variety of cellular and organismal functions, ultimately precipitating the development and progression of major diseases. GABAAR: g-amino butyric acid type A receptors; ACBP/DBI: acyl-CoA binding protein/diazepam-binding inhibitor.

DBI, also known as acyl-CoA binding protein (ACBP) due to its capacity to interact with activated fatty acids, has recently been implicated in the aging process and the development of age-related diseases. Indeed, ACBP/DBI fulfills the criteria for a “geroprotein” (a protein encoded by a “gerogene”) because (i) its plasma concentration correlates with age and age-related diseases in humans and (ii) its experimental inhibition reduces pathological aging in mouse models[24,25]. Thus, circulating plasma levels of ACBP/DBI steadily increase with age in obstensibly healthy individuals[26] and rise further in persons at risk of developing cardiovascular diseases or cancers[27,28]. The levles also correlate with cardiometabolic risk factors[29-31], and reach particularly high concentrations in acute or chronic conditions, including severe infections[32-34], ischemic heart disease[35,36], diabetes[37], various types of cancer[29] and terminal frailty[38,39].

Moreover, genetic or antibody-mediated inhibition of ACBP/DBI delays cellular senescence and pathological aging in mice caused by specific drugs or toxins (such as bleomycin, carbon tetrachloride, cisplatin or doxorubicin, which affect the lung, liver, kidney and heart, respectively) or the knockout of Zmpste24 (a genetic defect that induces accelerated aging in the form of a progeroid syndrome)[27,40-42]. In addition, in mouse models of age-related diseases, ACBP/DBI neutralization attenuates or delays the onset of metabolic syndrome (adiposity, hepatic steatosis, dyslipidemia, hyperglycemia, and hyperinsulinemia)[41,43-45], multiple cancers (breast cancer, fibrosarcoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, and non-small cell lung cancer)[28,46], cardiovascular diseases (heart failure and myocardial infarction)[27,41], and knee osteoarthritis[47]. At least some of these positive effects of ACBP/DBI inhibition have been attributed to the induction of autophagy, a key antiaging mechanism[41,44].

Clinically used benzodiazepines have been developed for their central nervous system effects, and have been designed to cross the blood-brain barrier due to their lipophilicity[48]. In contrast, ACBP/DBI does not cross this barrier, and its peripheral administration (outside of the central nervous system) does not elicit the same psychotropic effects as benzodiazepines[49]. Moreover, there is no evidence that extracellular ACBP/DBI can access the intracellular ‘peripheral benzodiazepine receptor’, which is the intracellular translocator protein (TSPO) located at mitochondria[50]. This further contributes to differences in the pharmacological effects of benzodiazepines and peripherally administered ACBP/DBI. The latter primarily stimulates food intake and lipoanabolic reactions leading to weight gain[49], an effect not observed with classical benzodiazepines.

3. Widespread Use, Misuse, and Abuse of Benzodiazepines

First introduced in the second half of the twentieth century as a safer alternative to barbiturates, benzodiazepines are widely used for their anxiolytic, sedative-hypnotic, muscle relaxant, anticonvulsant, and amnestic properties[51]. Consequently, they are prescribed for various neuropsychiatric conditions (including anxiety, agitation, insomnia, restless leg syndrome, seizures, panic attacks, and vertigo), and palliative care (to treat anxiety, dyspnea, seizures, or terminal agitation). Prescription rates among individuals over 60 vary significantly across countries, ranging from approximately 9% in the U.S. to as much as 20-30% in parts of Europe and Canada[52,53]. The global average of benzodiazepine use among community-dwelling seniors is around 15%. Notably, 30-75% of these older adults are long-term users (≥ 6 months of supply), reflecting the high addictive potential of benzodiazepines and the risk of rebound anxiety, insomnia and seizures following abrupt discontinuation[54].

Benzodiazepines are often classified as “potentially inappropriate medication” (PIM), indicating that (i) their therapeutic benefits are limited or outweighed by risk, especially in older individuals, and/or (ii) safer or more effective alternatives are available[9,10]. The European STOPP assesses PIM and advises against the prolonged (> 4 weeks) use of benzodiazepine for the treatment of insomnia and anxiety[10,55]. Similarly, the American Geriatrics Society 2023 updated Beers Criteria strongly recommends avoiding benzodiazepines in the elderly[9]. Indeed, common indications for benzodiazepines can be treated by safer or more effective therapies, including serotonin reuptake inhibitors or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (for acute or chronic anxiety), specific anticonvulsants (for seizures), or interventions targeting underlying causes (for agitation and insomnia)[9,10].

Beyond their medical (mis)use, benzodiazepines are also consumed recreationally in the form of illegal ‘designer benzodiazepines’, which are often synthesized to circumvent drug regulations. Such agents, which are highly addictive and can induce severe withdrawal syndromes, are generally highly potent, short-acting, inexpensive and easily available through street markets or online. Although their use alone is associated with a relatively low risk of fatal overdoses, they are frequently combined with other drugs including opioids, which dramatically increase the odds of fatality[56,57]. These designer benzodiazepines are mostly consumed by younger adults, in contrast to the (ab)use of conventional benzodiazepines by the older. Their long-term effects on morbidity and mortality have not been systematically investigated.

4. Benzodiazepine Effects on Age-Related Diseases

Given that the endozepine ACBP/DBI promotes pathological aging (see above), it is pertinent to ask whether benzodiazepines might similarly contribute to pathological aging. Although there is no evidence that benzodiazepine medication affects commonly studied biomarkers of aging (such as methylation clocks or telomere length of peripheral blood mononuclear cells), substantial epidemiological data indicate that benzodiazepines can accelerate or exacerbate the clinical course of several age-related pathologies. This association also applies to cardiovascular disease, cancer, neurodegeneration, and infectious disease, as shown in numerous retrospective studies and some prospective clinical analyses (Table 1).

| Age-related disease category | Ref. | Study design* | Outcome worsened by BZD use | HR [CI95], adjusted (if applicable) | Mean age (SD) |

| Cardio-vascular diseases | [58] | RCS (N = 74,715; 12,954 users) | Incidence of sudden cardiac arrest in cardiovascular disease patients, dose-dependent risk | 2.01 [1.42, 2.83] | 55 (15) |

| [59] | RCS (N = 4,837; 433 users) | CVD-related mortality following myocardial infarction | 1.43 [1.14, 1.81] | 69 (6) | |

| [60] | RCS (N = 854; 242 users) | Mortality in patients with cardiac failure | 1.36 [1.06, 1.75] | 71 (13) | |

| [61] | PCS (N = 124,321; 1,424 users) | Incident CHD, HF, and CVD during median follow-up of 14.3 years | CHD: 1.37 [1.18-1.60] HF: 1.60 [1.27-2.03] CVD: 1.81 [1.31-2.51] | 58 (3) | |

| Neuro-degeneration | [62] | PCS (N = 1,063; 85 users) | Incidence of dementia | 1.60 [1.08, 2.38] | 78 (NA) |

| [63] | PCS (N = 1,449; 55 users) | Incidence of dementia | 1.88 [1.03, 3.44] | 73 (9) | |

| [64] | PCS (N = 8,240; 1,246 users) | Incidence of dementia in long half-life BZD users | 1.62 [1.11, 2.37] | 74 (5) | |

| [65] | MetaA (N = 171,939; 9,552 users) | Incidence of dementia, dose-dependent | 1.51 [1.17, 1.96] | 75 (NA) | |

| [66] | MetaA (N = 2,953,980; 560,466 users) | Incidence of dementia or Alzheimer’s disease | 1.11 [1.04-1.18] | NA | |

| [67] | RCS (N = 5,443; 2,701 users) | Loss of hippocampus volume | - | 71 (8) | |

| [68] | PCS (N = 139,103; 26,872 users) | 180-day mortality in hospitalized patients with Alzheimer disease and related dementias | 1.41 [1.38-1.44] | 88 (8) | |

| Cancer | [69] | MetaA (N = 1,897,600) | Incidence of cancer | 1.19 [1.16, 1.21] | 58 (NA) |

| [70] | MetaA (N = 2,482,625) | Incidence of cancer, dose-dependent risk | 1.25 [1.15, 1.36] | NA | |

| [71] | CCS (N = 1,344,089; 268,244 users) | Incidence of cancer | 1.09 [1.04,1.14] | 65 (NA) | |

| [72] | PCS (N = 34,084; 1,365 users) | Incidence of lung cancer during follow up | 2.575 [1.02, 6.53] | 47 (0.2) | |

| [73] | RCS (N = 205; 51 users) | NSCLC patients’ progression following PD1 blockade | 1.50 [0.97, 2.23] | 66 (9) | |

| [74] | RCS (N = 556; 57 users) | NSCLC patients’ overall survival following PD1 blockade | 1.49 [1.05, 2.11] | 64 (17) | |

| [74] | RCS (N = 31,479; 11,878 users) | NSCLC patients’ overall survival following PD1 blockade | 1.08 [1.04,1.12] | 65 (10) | |

| [75] | RCS (N = 215; 56 users) | NSCLC patients’ progression following PD(L)1 blockade | 1.80 [1.13, 2.86] | 70 (NA) | |

| Infectious diseases | [76] | RCS (N = 1,427,792; 713,896 users) | Incidence of serious infections, dose-dependent risk | 1.83 [1.79, 1.89] | 43 (14) |

| [77] | MetaA (N = 1,595,717) | Incidence of pneumonia, attenuated risk upon cessation | 1.25 [1.09, 1.44] | NA |

BZD: benzodiazepine; CCS: case-control study; HR: hazard ratio; RCS: retrospective cohort study; PCS: prospective cohort study; NA, not applicable; MetaA: meta-analysis; SD: standarLd deviation; CHD: coronary heart diseases; HF: heart failure; CVD: cardiovascular death; PD: Parkinson’s disease.

4.1 Cardiovascular disease

In patients with cardiovascular disease, the initiation of benzodiazepine treatment is associated with a dose-dependent increase in sudden cardiac arrest[58]. Similarly, benzodiazepine use is linked to increased mortality in patients after myocardial infarction[59] or with heart failure[60]. In a propensity score matched cohort of UK Biobank participants with insomnia, its use was correlated with higher odds of developing coronary heart disease, heart failure and cardiovascular death[61] (Table 1). Accordingly, diazepam depresses cardiac output and arterial blood pressure in rats, independent of its effects on the central nervous system[78].

4.2 Dementia and neurodegeneration

Long-term use (> 3 years) of long-lived (half live > 20 hours) benzodiazepines is associated with an increased risk of incident dementia[62,64]. This observation was confirmed by a meta-analysis on 10 cohorts enrolling a total of 171,939 subjects[65]. Another meta-analysis of 10 case-control and 9 cohort studies (total 2,953,980 patients), demonstrated a statistically significant relationship between benzodiazepine use and the development of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease (RR = 1.11, 95% CI: 1.04-1.18)[66]. Of note, repeated brain MRI revealed that high cumulative doses of benzodiazepines were linked to accelerated hippocampal volume loss[67]. In a case control study on women with breast cancer from the Korean National Health Insurance claims database (n = 197,917), concomitant use of benzodiazepines and antidepressants (n = 5,304) was found to be associated with a elevated risk of developing dementia compared with the use of antidepressants alone (1,326) (hazard ratio, 1.807; 95% confidence interval, 1.26-2.58)[79].

In a national study based on Medicare records, patients with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in hospice care (n = 139,103) were analyzed. None of them had used benzodiazepines or antipsychotics in the prior 6 months. Those who received benzodiazepines (n = 26,872) were matched 1:1 with nonusers on enrollment timing, age, sex, comorbidity, cognitive function, and baseline central nervous system medications. Initiation of benzodiazepine treatment was associated with increased 180-day mortality compared with controls (HR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.38-1.44). Similarly, initiation of antipsychotic therapy (n = 10,240) was linked to a higher 180-day mortality relative to matched controls (HR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.12-1.20), although the magnitude of this detrimental effect appears to be notably smaller than that of benzodiazepines[68].

In the national Finnish register-based FINPARK cohort, 18 651 persons diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease (PD) in 1996-2015 were compared to PD-free persons matched for age (± 1 year), sex and region (n = 127 806). Importantly, people with PD initiated the use of benzodiazepines and benzodiazepine-related drugs (BZDR) more frequently than the control group without PD (39.0% vs. 25.9%), with a relatively higher proportion of benzodiazepine use among BZDR (53.3% vs. 42.2%, p < 0.001). This overuse of BZDR occurred 2 years before PD diagnosis and actually peaked 6 months prior[80]. Although this overuse may be attributed to the treatment for non-specific psychiatric symptoms—including anxiety—preceding the PD-specific motor disorder[81], it is also possible that BZDR use (and specifically that of benzodiazepines) increases the risk of developing clinically manifest PD. These observations raise the possibility that benzodiazepine use may promote the development of several neurodegenerative diseases (Table 1).

However, there are no convincing evidence that benzodiazepines induce neurodegeneration in rodents. Rather, long-term administration of moderate doses of diazepam appears to exert neuroprotective effects in rodent models of Alzheimer’s disease[82,83]. Similarly, intrathecal injection of the ACBP/DBI-derived octadecaneuropeptide (which also acts on GABAAR) attenuated cognitive impairments induced by amyloid-beta peptide in mice[84]. In contrast, diazepam inhibits hippocampal neurogenesis in a mouse mode of traumatic brain[85] and impairs hippocampal long-term potentiation in middle-aged mice[86], potentially explaining the selective effects of benzodiazepine on hippocampal volume in patients.

4.3 Cancer incidence and responses to immunotherapy

Several studies suggest that benzodiazepine use enhances the risk of developing cancer (Table 1). A meta-analysis of observational studies including 213,823 cancer patients and 1,683,780 controls without cancer reported a significant dose-dependent association between benzodiazepine use and overall cancer risk (pooled relative risk [RR] 1.19, 95% CI 1.16-1.21)[69]. Another meta-analysis, including 313,647 cancer patients and 2,168,978 controls, came to a similar conclusion (RR = 1.25, 95% CI 1.15-1.36), revealing the highest risk for brain cancer (RR = 2.06, 95% CI 1.76-2.43)[70]. This finding may reflect the propensity of benzodiazepines to accumulate in the central nervous system and/or that GABAA receptors in the brain[48]. In the Danish nationwide register, 152,510 individuals with first-time cancer were matched (1:8) by age and gender to 1,220,317 cancer-free controls. In this study, long-term use (≥ 500 daily doses within 1 to 5 years prior to the index date) of BZRD increased the adjusted odds ratio (OR) for all cancers by 1.09 (95% CI 1.04-1.14)[71]. Another study using the same registry included 94,923 oncological patients and 759,334 age- and sex-matched (1:8) controls, and applied propensity score (PS) calibration to eliminate confounding factors such as self-reported health, comorbidities, alcohol, tobacco use, other medications, physical activity and obesity. This confirmed that BZRD use was coupled to an elevated cancer risk (OR = 1.09, 95% CI 1.00-1.19)[87].

A recent study addressed the association between benzodiazepine use and the risk of developing lung carcinomas[72]. Lung cancer risk was analyzed in 34,084 US adults, aged 47 ± 0.2 years, from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey study. This risk is 4.643 times higher in benzodiazepine users compared to nonusers (95% CI: 2.096, 10.283). This association remained significant (OR: 2.575, 95% CI: 1.015, 6.529) after adjusting for other variables including age and sex, ethnicity, education level, poverty-to-income ratio, established cardiovascular and cancer risk factors (alcohol, body mass index, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, smoke), and other cancers[72].

In mouse experiments, intraperitoneal injection of diazepam reversed the immunostimulatory effects of anti-ACBP/DBI treatment in the context of chemoimmunotherapy combining oxaliplatin and anti-programmed death-1 (PD-1) antibody, suggesting that diazepam may exert an identical immunosurveillance effect as ACBP/DBI[73].

Accordingly, retrospective analyses of patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with PD-1 or PD-1 ligand-1 (PD-L1) blockade revealed adverse effects of benzodiazepine use on patient prognosis across four independent cohorts comprising 203, 314, 556 and 31,479 patients, respectively[73-75]. These support the notion that benzodiazepines can subvert immunotherapy effects in cancer patients exactly as they do in mice. One of the studies[75] reported that benzodiazepines reduced immune-related adverse events induced by PD-1/PD-L1 blockade[75], consistent with the interpretation that the drugs suppress both desired (anticancer) and unwarranted (autoimmune) responses. Furthermore, analyses of medical records from 3,510 breast cancer patients treated at three Taiwanese medical centers revealed that BZDR use (n = 1053) was associated with greatly increased mortality (HR = 1.34; 95% CI: 1.02, 1.76)[88]. However, whether this effect is mediated through inhibition of cancer immunosurveillance remains to be determined.

4.4 Bacterial and viral infections

A recent study based on the Swedish national registry examined individuals under 65 years who (ab)used BZDR (n = 713,896 users) compared to matched (1:1) controls by age, sex and residence. The results demonstrated that BZDR use was associated with an increased risk of viral or bacterial infections in all body sites (HR = 1.83, 95% CI 1.79-1.89). The BZDR-linked risk of serious infection was corroborated by both a comparison of 434,900 BZDR recipients with 428,074 patients taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (HR = 1.33, 95% CI 1.30-1.35), and a co-twin cohort analysis of 9197 BZDR-treated twins versus their non-treated siblings (HR = 1.55, 95% CI 1.23-1.97). The HR for infection was comparable across different BZDR types but increased with cumulative BZDR dosage[76]. A meta-analysis of clinical studies including patients with pneumonia (58,573 with BZDR and 221,916 controls) found that recent BZDR use (until 90 days before the index data) incremented the risk of pneumonia. This effect was pronounced for the individuals younger than 65 years, with an 80% increase in lung infections[77].

These human data (Table 1) are supported by preclinical experiment showing that diazepam enhances the susceptibility of rodents to respiratory or peritoneal infections caused by bacteria and viruses, in line with the notion that diazepam can mediate immunosuppression[89-92].

In essence, there are several human age-related diseases (dementia, cardiovascular disorders, cancer, and infection) that are accelerated or aggravated in individuals using benzodiazepines (Figure 1), consistent with an increase in overall mortality among benzodiazepine users[93]. Part of the clinical associations may be affected by confounding factors such as patients’ clinical presentation, anxiety level, co-medications, alcohol or drug use, and socioeconomic status. Of note, socioeconomic deprivation is coupled to higher benzodiazepine use, as documented in Australia[94], England[95], Ireland[96], Sweden[97], and the US[98]. Nonetheless, several of the aforementioned studies have been corrected for deprivation and other sociodemographic parameters. Moreover, preclinical experiments suggest a causative relationship between benzodiazepine use and several age-related diseases, especially heart failure, cancer and infectious disease (Table 1).

5. Discussion

The present analysis elucidates a potential mechanistic and epidemiological link between exogenous benzodiazepines and the endogenous protein ACBP/DBI, implicating both in the modulation of aging and age-related pathologies. ACBP/DBI, functioning as a positive allosteric modulator of GABAARs containing α1 and γ2 subunits, appears to act as an endogenous pro-aging factor or “geroprotein”, with its circulating levels correlating positively with age and multiple morbid conditions, including cardiovascular disease, cancer, metabolic syndrome, and frailty.

The pharmacodynamic overlap between ACBP/DBI and benzodiazepines, both enhancing GABAergic neurotransmission via GABAARs, raises the provocative hypothesis that benzodiazepines may pharmacologically mimic ACBP/DBI and thus promote similar detrimental effects on organismal aging. Supporting this conjecture, retrospective clinical studies associate benzodiazepine use with increased risks of diverse age-related disorders, including cardiovascular events, neurodegeneration (particularly dementia), malignancies, and infections, all of which contribute to elevated all-cause mortality. Mechanistically, these effects may be mediated, at least in part, through benzodiazepine-induced immunosuppression, heightened inflammation, inhibited autophagy, and metabolic alterations. Several of these parallel the biological activity of DBI in preclinical models (Figure 1). Moreover, benzodiazepine use is linked to persistent alterations in the gut microbiota detectable years after drug discontinuation[99]. In cancer patients, such benzodiazepine-induced dysbiosis correlates with poorer cancer immunotherapy’s outcome[74]. However, the precise mechanisms underlying these microbial shifts remain poorly understood.

Importantly, epidemiological data suggest a dose-response relationship between long-term benzodiazepine exposure and adverse outcomes, particularly regarding cancer incidence and neurodegenerative decline, reinforcing concerns that benzodiazepine exposure could exacerbate or unmask latent pathologies in aging individuals. Notably, evidence from both murine models and clinical cohorts receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors indicates that benzodiazepines can impair cancer immunosurveillance, supporting a potential immunomodulatory and tumor-promoting role for these agents.

Despite the compelling correlation between benzodiazepine use and age-related diseases, several limitations must temper causal interpretations. First, most clinical data are observational or retrospective, rendering them inherently susceptible to confounding by indication, reverse causality, and selection bias. For instance, conditions such as anxiety, insomnia, or early cognitive decline (which may be early manifestations of neurodegenerative or systemic diseases) often prompt benzodiazepine prescriptions, complicating efforts to distinguish cause from effect. Second, while many studies attempt to adjust for socioeconomic status and comorbidities, residual confounding is possible, particularly given the well-documented association between socioeconomic deprivation and increased benzodiazepine use. Third, preclinical evidence, though supportive, is restricted in scope and often constrained to specific disease models or rodent strains, raising questions about translational relevance. Another limitation include the absence of direct molecular evidence of aging acceleration (e.g., epigenetic, proteomic or telomeric clocks) in benzodiazepine users, precluding definitive classification of the drugs as gerontogens. In addition, while DBI primarily acts peripherally and does not cross the blood-brain barrier, benzodiazepines are centrally acting agents, raising questions about the spatial overlap of their respective effects. Other key differences involve distinct interactions with peripheral benzodiazepine receptors (e.g., TSPO), which may confer divergent downstream effects on mitochondrial function and inflammation.

In light of the accumulating evidence that benzodiazepines may accelerate age-related decline and exacerbate multiple morbidities, coupled with their widespread—often inappropriate—use in vulnerable populations, a precautionary approach is warranted (Figure 1). Until definitive mechanistic and longitudinal clinical data become available, it would be prudent to limit the long-term prescription of benzodiazepines, unless no safer alternatives exist. Indeed, benzodiazepines can be replaced in many cases by selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, anticonvulsants, or non-pharmacological treatments. Preclinical evidence indicates that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may stimulate anticancer immune responses[100-102]. Similar immunostimulatory effects have been reported for the α2-adrenergic agonist dexmedetomidine, serving as an adjunct agent in cancer care[103]. Collectively, these agents may represent particularly useful alternatives to benzodiazepines for managing agitation, anxiety, depression, neuropathic or perioperative pain, and delirium in patients with cancer.

A moratorium against benzodiazepines should extend to the entire population, not only elderly adults, due to the potential pro-aging effects that could compromise long-term population health, analogous to the premature morbidity and mortality decades after DNA-damaging chemotherapy or radiotherapy in children and young adults[104,105]. Regulatory agencies and clinical guidelines should re-evaluate the risk/benefit profile of benzodiazepines through the lens of aging biology, public health, and pharmacovigilance, to prevent inadvertent iatrogenic acceleration of senescence and chronic disease.

Authors contribution

Kroemer G: Conceptualization, writing-original draft.

Montégut L: Investigation, writing-original draft.

Conflict of interest

Léa Montégut and Guido Kroemer are inventors of patent applications covering the targeting of ACBP/DBI for combating age-related diseases. Guido Kroemer has been holding research contracts with Daiichi Sankyo, Eleor, Kaleido, Lytix Pharma, PharmaMar, Osasuna Therapeutics, Samsara Therapeutics, Sanofi, Sutro, Tollys, and Vascage. Guido Kroemer is on the Board of Directors of the Bristol Myers Squibb Foundation France. He is a scientific co-founder of everImmune, Osasuna Therapeutics, Samsara Therapeutics, and Therafast Bio. Guido Kroemer is in the scientific advisory boards of Hevolution, Institut Servier, and Rejuveron Life Sciences/Centenara Labs AG. He is the inventor of patents covering therapeutic targeting of aging, cancer, cystic fibrosis and metabolic disorders. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results. Guido Kroemer is the Editor-in-Chief of Geromedicine. The authors declare no other conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR) under the France 2030 programme (reference numbers 21-ESRE-0028, ESR/Equipex+ Onco-Pheno-Screen; ANR-21-RHUS-0017 IMMUNOLIFE; ANR-23-RHUS-0010 LUCA-pi; ANR-22-CE14-0066 VIVORUSH; ANR-23-CE44-0030 COPPERMAC; ANR-23-R4HC-0006 Ener-LIGHT), the European Research Council Advanced Investigator Award (ERC-2021-ADG, Grant No. 101052444), the European Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation programmes Oncobiome (grant agreement No. 825410) and Prevalung (grant agreement No. 101095604), the Institut National du Cancer (INCa), the Institut Universitaire de France, the IdEx Université de Paris Cité (ANR-18-IDEX-0001) through the Immuno-Onco study, as well as support to Guido Kroemer from the Ligue contre le Cancer (équipes labellisées; project acronym ICD-Cancer), the Hevolution Network on Senescence in Aging (reference HF-E Einstein Network), the PAIR-Obésité programme (INCa_18713), the Seerave Foundation, and the SIRIC Cancer Research and Personalized Medicine programme (CARPEM, SIRIC CARPEM INCa-DGOS-Inserm-ITMO Cancer_18006) funded by the Institut National du Cancer, the Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé, and INSERM.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

References

-

1. Hersberger KE, Boeni F, Arnet I. Dose-dispensing service as an intervention to improve adherence to polymedication. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2013;6(4):413-421.[DOI]

-

2. Marengoni A, Angleman S, Melis R, Mangialasche F, Karp A, Garmen A, et al. Aging with multimorbidity: A systematic review of the literature. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10(4):430-439.[DOI]

-

3. Gronich N. Central nervous system medications: Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic considerations for older adults. Drugs Aging. 2024;41(6):507-519.[DOI]

-

4. Hilmer SN, McLachlan AJ, Le Couteur DG. Clinical pharmacology in the geriatric patient. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2007;21(3):217-230.[DOI]

-

5. Mangoni AA, Jackson SHD. Age-related changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: Basic principles and practical applications. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;57(1):6-14.[DOI]

-

6. Binder EF, Schechtman KB, Ehsani AA, Steger-May K, Brown M, Sinacore DR, et al. Effects of exercise training on frailty in community-dwelling older adults: Results of a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(12):1921-1928.[DOI]

-

7. Budnitz DS, Lovegrove MC, Shehab N, Richards CL. Emergency hospitalizations for adverse drug events in older Americans. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(21):2002-2012.[DOI]

-

8. Leipzig RM, Cumming RG, Tinetti ME. Drugs and falls in older people: A systematic review and meta-analysis: I. Psychotropic drugs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(1):30-39.[DOI]

-

9. By the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2023 updated AGS Beers Criteria(R) for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;71:2052-2081.[DOI]

-

10. O’Mahony D, Cherubini A, Guiteras AR, Denkinger M, Beuscart J-B, Onder G, et al. Stopp/start criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: Version 3. Eur Geriatr Med. 2023;14(4):625-632.[DOI]

-

11. Kales HC, Gitlin LN, Lyketsos CG. Assessment and management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. BMJ. 2015;350:h369.[DOI]

-

12. Woolcott JC, Richardson KJ, Wiens MO, Patel B, Marin J, Khan KM, et al. Meta-analysis of the impact of 9 medication classes on falls in elderly persons. Arch Intern Med. 2009169(21);1952-1960.[DOI]

-

13. Sink KM, Holden KF, Yaffe K. Pharmacological treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia: A review of the evidence. JAMA. 2005;293(5):596-608.[DOI]

-

14. Reeve E, Shakib S, Hendrix I, Roberts MS, Wiese MD. The benefits and harms of deprescribing. Med J Aust. 2014;201(7):386-389.[DOI]

-

15. Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, Potter K, Le Couteur D, Rigby D, et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: The process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):827-834.[DOI]

-

16. Dumitru I, Neitz A, Alfonso J, Monyer H. Diazepam binding inhibitor promotes stem cell expansion controlling environment-dependent neurogenesis. Neuron. 2017;94(1):125-137.e125.[DOI]

-

17. Guidotti A, Forchetti CM, Corda MG, Konkel D, Bennett CD, Costa E. Isolation, characterization, and purification to homogeneity of an endogenous polypeptide with agonistic action on benzodiazepine receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 1983;80(11):3531-3535.[DOI]

-

18. Sigel E. Mapping of the benzodiazepine recognition site on GABA-A receptors. Curr Top Med Chem. 2002;2(8):833-839.[DOI]

-

19. Tonon MC, Vaudry H, Chuquet J, Guillebaud F, Fan J, Masmoudi-Kouki O, et al. Endozepines and their receptors: Structure, functions and pathophysiological significance. Pharmacol Ther. 2020;208:107386.[DOI]

-

20. Sun C, Zhu H, Clark S, Gouaux E. Cryo-em structures reveal native gabaa receptor assemblies and pharmacology. Nature. 2023;622(7981):195-201.[DOI]

-

21. Goldschen-Ohm MP. Benzodiazepine modulation of gabaa receptors: A mechanistic perspective. Biomolecules. 2022;12(12):1784.[DOI]

-

22. Da Settimo F, Taliani S, Trincavelli ML, Montali M, Martini C. GABAA/Bz receptor subtypes as targets for selective drugs. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14(25):2680-701.[DOI]

-

23. Kaila K, Voipio J. Postsynaptic fall in intracellular ph induced by gaba-activated bicarbonate conductance. Nature. 1987;330(6144):163-165.[DOI]

-

24. Kroemer G, Maier AB, Cuervo AM, Gladyshev VN, Ferrucci L, Gorbunova V, et al. From geroscience to precision geromedicine: Understanding and managing aging. Cell. 2025;188(8):2043-2062.[DOI]

-

25. López-Otín C, Maier AB, Kroemer G. Gerogenes and gerosuppression: The pillars of precision geromedicine. Cell Res. 2024;34(7):463-466.[DOI]

-

26. Joseph A, Moriceau S, Sica V, Anagnostopoulos G, Pol J, Martins I, et al. Metabolic and psychiatric effects of acyl coenzyme a binding protein (acbp)/diazepam binding inhibitor (dbi). Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(7):502.[DOI]

-

27. Montégut L, Joseph A, Chen H, Abdellatif M, Ruckenstuhl C, Motiño O, et al. High plasma concentrations of acyl-coenzyme a binding protein (acbp) predispose to cardiovascular disease: Evidence for a phylogenetically conserved proaging function of acbp. Aging Cell. 2023;22(1):e13751.[DOI]

-

28. Montégut L, Liu P, Zhao L, Pérez-Lanzón M, Chen H, Mao M, et al. Acyl-coenzyme a binding protein (ACBP) - a risk factor for cancer diagnosis and an inhibitor of immunosurveillance. Mol Cancer. 2024;23(1):187.[DOI]

-

29. Eldjarn GH, Ferkingstad E, Lund SH, Helgason H, Magnusson OT, Gunnarsdottir K, et al. Large-scale plasma proteomics comparisons through genetics and disease associations. Nature. 2023;622(7982):348-358.[DOI]

-

30. Ferkingstad E, Sulem P, Atlason BA, Sveinbjornsson G, Magnusson MI, Styrmisdottir EL, et al. Large-scale integration of the plasma proteome with genetics and disease. Nat Genet. 2021;53(12):1712-1721.[DOI]

-

31. Joseph A, Chen H, Anagnostopoulos G, Montégut L, Lafarge A, Motiño O, et al. Effects of acyl-coenzyme a binding protein (ACBP)/diazepam-binding inhibitor (DBI) on body mass index. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(6):599.[DOI]

-

32. Clavier T, Tonon M-C, Foutel A, Besnier E, Lefevre-Scelles A, Morin F, et al. Increased plasma levels of endozepines, endogenous ligands of benzodiazepine receptors, during systemic inflammation: A prospective observational study. Crit Care. 2014;18(6):633.[DOI]

-

33. Isnard S, Mabanga T, Royston L, Berini CA, Bu S, Aiyana O, et al. Extracellular acyl-CoA-binding protein as an independent biomarker of COVID-19 disease severity. Front Immunol. 2025;15:1505752.[DOI]

-

34. Isnard S, Royston L, Lin J, Fombuena B, Bu S, Kant S, et al. Distinct plasma concentrations of acyl-coA-binding protein (ACBP) in HIV progressors and elite controllers. Viruses. 2022;14(3):453.[DOI]

-

35. Addona TA, Shi X, Keshishian H, Mani DR, Burgess M, Gillette MA, et al. A pipeline that integrates the discovery and verification of plasma protein biomarkers reveals candidate markers for cardiovascular disease. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(7):635-643.[DOI]

-

36. Mazidi M, Wright N, Yao P, Kartsonaki C, Millwood IY, Fry H, et al. Plasma proteomics to identify drug targets for ischemic heart disease. JACC. 2023;82(20):1906-1920.[DOI]

-

37. Gadd DA, Hillary RF, Kuncheva Z, Mangelis T, Cheng Y, Dissanayake M, et al. Blood protein assessment of leading incident diseases and mortality in the uk biobank. Nat Aging. 2024;4(7):939-948.[DOI]

-

38. Sathyan S, Ayers E, Gao T, Milman S, Barzilai N, Verghese J. Plasma proteomic profile of frailty. Aging Cell. 2020;19(9):e13193.[DOI]

-

39. Sathyan S, Ayers E, Gao T, Weiss EF, Milman S, Verghese J, et al. Plasma proteomic profile of age, health span, and all-cause mortality in older adults. Aging Cell. 2020;19(11):e13250.[DOI]

-

40. Montégut L, Lambertucci F, Moledo-Nodar L, Fiuza-Luces C, Rodríguez-López C, Serra-Rexach JA, et al. Acyl-coa-binding protein as a driver of pathological aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 2025;122(28):e2501584122.[DOI]

-

41. Motiño O, Lambertucci F, Anagnostopoulos G, Li S, Nah J, Castoldi F, et al. ACBP/DBI protein neutralization confers autophagy-dependent organ protection through inhibition of cell loss, inflammation, and fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 2022;119(41):e2207344119.[DOI]

-

42. Motiño O, Lambertucci F, Joseph A, Durand S, Anagnostopoulos G, Li S, et al. ACBP/DBI neutralization for the experimental treatment of fatty liver disease. Cell Death Differ. 2025;32(3):434-446.[DOI]

-

43. Anagnostopoulos G, Motiño O, Li S, Carbonnier V, Chen H, Sica V, et al. An obesogenic feedforward loop involving pparγ, acyl-coa binding protein and gabaa receptor. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13(4):356.[DOI]

-

44. Bravo-San Pedro JM, Sica V, Martins I, Pol J, Loos F, Maiuri MC, et al. Acyl-CoA-binding protein is a lipogenic factor that triggers food intake and obesity. Cell Metab. 2019;30(4):754-767.e759.[DOI]

-

45. Pan H, Tian A-L, Chen H, Xia Y, Sauvat A, Moriceau S, et al. Pathogenic role of acyl coenzyme a binding protein (ACBP) in cushing’s syndrome. Nat Metab. 2024;6(12):2281-2299.[DOI]

-

46. Li S, Motiño O, Lambertucci F, Pol J, Chen H, Pan L, et al. Neutralization of acyl coenzyme a binding protein for the experimental prevention and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Rep Med. 2025;6(7):102232.[DOI]

-

47. Nogueira-Recalde U, Lambertucci F, Montégut L, Motiño O, Chen H, Lachkar S, et al. Neutralization of acyl CoA binding protein (ACBP) for the experimental treatment of osteoarthritis. Cell Death Differ. 2025;32(8):1484-1498.[DOI]

-

48. El Balkhi S, Abbara C. Designer benzodiazepines: Effects, toxicity, and interactions. Ther Drug Monit. 2023;45(4):494-507.[DOI]

-

49. Chen H, Moriceau S, Joseph A, Mailliet F, Li S, Tolle V, et al. Acyl-coa binding protein for the experimental treatment of anorexia. Sci Transl Med. 2024;16(760):eadl0715.[DOI]

-

50. Gavish M, Veenman L. Regulation of mitochondrial, cellular, and organismal functions by TSPO. Adv Pharmacol. 2018;82:103-136.[DOI]

-

51. Lader M. Benzodiazepines revisited—will we ever learn? Addiction. 2011;106(12):2086-2109.[DOI]

-

52. Lukačišinová A, Reissigová J, Ortner-Hadžiabdić M, Brkic J, Okuyan B, Volmer D, et al. Prevalence, country-specific prescribing patterns and determinants of benzodiazepine use in community-residing older adults in 7 European countries. BMC Geriatr. 2024;24(1):240.[DOI]

-

53. Ma TT, Wang Z, Qin X, Ju C, Lau WCY, Man KKC, et al. Global trends in the consumption of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs in 67 countries and regions from 2008 to 2018: A sales data analysis. Sleep. 2023;46(10):zsad124.[DOI]

-

54. Woods JH, Katz JL, Winger G. Benzodiazepines: Use, abuse, and consequences. Pharmacol Rev. 1992;44(2):151-347.[DOI]

-

55. O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, O’Connor MN, Ryan C, Gallagher P. Stopp/start criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: Version 2. Age Ageing. 2015;44(2):213-218.[DOI]

-

56. Brunetti P, Giorgetti R, Tagliabracci A, Huestis MA, Busardò FP. Designer benzodiazepines: A review of toxicology and public health risks. Pharmaceuticals. 2021;14(6):560.[DOI]

-

57. van Amsterdam J, van den Brink W. Designer benzodiazepines: Availability, motives, and fatalities. A systematic narrative review of human studies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2025;272:112708.[DOI]

-

58. Mo C, Wang S, Li X, Li F, Jin C, Bai B, et al. Benzodiazepine use and incident risk of sudden cardiac arrest in patients with cardiovascular diseases. Sci Prog. 2024;107(4):00368504241295325.[DOI]

-

59. Liu S, Soedamah-Muthu SS, van Meerten SC, Kromhout D, Geleijnse JM, Giltay EJ. Use of benzodiazepine and Z-drugs and mortality in older adults after myocardial infarction. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2023;38(1):e5861.[DOI]

-

60. Ribeirinho-Soares P, Madureira S, Elias C, Gouveia R, Neves A, Amorim M, et al. Benzodiazepine use and mortality in chronic heart failure. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2023;133(10):16464.[DOI]

-

61. Xie Y, Zhu S, Wu S, Liu C, Shen J, Jin C, et al. Hypnotic use and the risk of cardiovascular diseases in insomnia patients. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2025;32(6):466-474.[DOI]

-

62. Billioti de Gage S, Bégaud B, Bazin F, Verdoux H, Dartigues JF, Pérès K, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of dementia: Prospective population based study. BMJ. 2012;345:e6231.[DOI]

-

63. Hou JH, Sun SL, Tan CC, Huang YM, Tan L, Xu W. Relationships of hypnotics with incident dementia and alzheime’s disease: A longitudinal study and meta-analysis. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2024;11(1):117-129.[DOI]

-

64. Shash D, Kurth T, Bertrand M, Dufouil C, Barberger-Gateau P, Berr C, et al. Benzodiazepine, psychotropic medication, and dementia: A population-based cohort study. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(5):604-613.[DOI]

-

65. He Q, Chen X, Wu T, Li L, Fei X. Risk of dementia in long-term benzodiazepine users: Evidence from a meta-analysis of observational studies. J Clin Neurol. 2019;15(1):9-19.[DOI]

-

66. Vakili K, Fathi M, Ebrahimi R, Ahmadian S, Moafi M, Ebrahimi MJ, et al. Use of drugs affecting gabaa receptors and the risk of developing alzheimer’s disease and dementia: A meta-analysis and literature review. Mol Neurobiol. 2025;62(7):9449-9468.[DOI]

-

67. Hofe Iv, Stricker BH, Vernooij MW, Ikram MK, Ikram MA, Wolters FJ. Benzodiazepine use in relation to long-term dementia risk and imaging markers of neurodegeneration: A population-based study. BMC Med. 2024;22(1):266.[DOI]

-

68. Gerlach LB, Zhang L, Kim HM, Teno J, Maust DT. Benzodiazepine or antipsychotic use and mortality risk among patients with dementia in hospice care. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(10):e2537551.[DOI]

-

69. Kim HB, Myung SK, Park YC, Park B. Use of benzodiazepine and risk of cancer: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Cancer. 2017;140(3):513-525.[DOI]

-

70. Zhang T, Yang X, Zhou J, Liu P, Wang H, Li A, et al. Benzodiazepine drug use and cancer risk: A dose–response meta analysis of prospective cohort studies. Oncotarget. 2017;8(60):102381.[DOI]

-

71. Pottegård A, Friis S, Andersen M, Hallas J. Use of benzodiazepines or benzodiazepine related drugs and the risk of cancer: A population-based case-control study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;75(5):1356-1364.[DOI]

-

72. Wu T, Ma X, Zuo P, Chen S, Tang X, Zhang X, et al. Association between benzodiazepines use and lung cancer in u.S. Adults: Results from the national health and nutrition examination survey. Medicine. 2025;104(43):e45357.[DOI]

-

73. Montégut L, Derosa L, Messaoudene M, Chen H, Lambertucci F, Routy B, et al. Benzodiazepines compromise the outcome of cancer immunotherapy. OncoImmunology. 2024;13(1):2413719.[DOI]

-

74. Montégut L, Rousseau A, Ungolo C, Derosa L, Fidelle M, Alves Costa Silva C, et al. Benzodiazepines interfere with the efficacy of pembrolizumab-based cancer immunotherapy. Results of a nationwide cohort study including over 50,000 participants with advanced lung cancer. OncoImmunology. 2025;14(1):2528955.[DOI]

-

75. Takagaki K, Ohno Y, Otsuki T, Kubota A, Kijima T, Tanaka T. Impact of exposure to benzodiazepines on adverse effects and efficacy of pd-1/pd-l1 blockade in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Thorac Cancer. 2025;16(9):e70081.[DOI]

-

76. Wang X, Isomura K, Lichtenstein P, Kuja-Halkola R, D’Onofrio BM, Brikell I, et al. Incident benzodiazepine and Z-drug use and subsequent risk of serious infections. CNS Drugs. 2024;38(10):827-838.[DOI]

-

77. Sun G, Zhang L, Zhang L, Wu Z, Hu D. Benzodiazepines or related drugs and risk of pneumonia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34(4):513-521.[DOI]

-

78. Strubelt O. Hemodynamic failure induced by narcotic and toxic doses of 12 CNS depressants in intact and pithed rats. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1980;246(2):264-276.[PubMed]

-

79. Kim T, Lee HS, Jeon S, Kim D, Kim E, Park WC, et al. Association between benzodiazepine and dementia risk in treating depression after breast cancer diagnosis: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Yonsei Med J. 2025;66(9):564-573.[DOI]

-

80. Lonka V, Hartikainen S, Tiihonen M, Koponen M, Tolppanen A-M. The incidence of benzodiazepine and benzodiazepine-related drug use in people with and without parkinson’s disease—a nationwide cohort study. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2025;137(5):e70123.[DOI]

-

81. Schrag A, Horsfall L, Walters K, Noyce A, Petersen I. Prediagnostic presentations of parkinson’s disease in primary care: A case-control study. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(1):57-64.[DOI]

-

82. Chen J, Zhang M, Shen Z, Tang M, Zeng Y, Bai D, et al. Low-dose diazepam improves cognitive function in app/ps1 mouse models: Involvement of ampa receptors. Brain Res. 2024;1845:149207.[DOI]

-

83. Pilipenko V, Narbute K, Pupure J, Rumaks J, Jansone B, Klusa V. Neuroprotective action of diazepam at very low and moderate doses in alzheimer’s disease model rats. Neuropharmacology. 2019;144:319-326.[DOI]

-

84. He Y, Li J, Yi L, Li X, Luo M, Pang Y, et al. Octadecaneuropeptide ameliorates cognitive impairments through inhibiting oxidative stress in alzheimer’s disease models. J Alzheimers Dis. 2023;92(4):1413-1426.[DOI]

-

85. Villasana LE, Peters A, McCallum R, Liu C, Schnell E. Diazepam inhibits post-traumatic neurogenesis and blocks aberrant dendritic development. J Neurotrauma. 2019;36(16):2454-2467.[DOI]

-

86. Furukawa T, Nikaido Y, Shimoyama S, Masuyama N, Notoya A, Ueno S. Impaired cognitive function and hippocampal changes following chronic diazepam treatment in middle-aged mice. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021;13:777404.[DOI]

-

87. Thygesen LC, Pottegård A, Ersbøll AK, Friis S, Stürmer T, Hallas J. External adjustment of unmeasured confounders in a case–control study of benzodiazepine use and cancer risk. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83(11):2517-2527.[DOI]

-

88. Yang WCV, Lin YY, Ding JL, Hung CS, Nguyen PA, Zhang BX, et al. Long-term treatment with benzodiazepines and related z-drugs exacerbates breast cancer: Clinical evidence and molecular mechanisms. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2025;30(1):75.[DOI]

-

89. Domingues-Junior M, Pinheiro SR, Guerra JL, Palermo-Neto J. Effects of treatment with amphetamine and diazepam on mycobacterium bovis-induced infection in hamsters. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2000;22(3):555-574.[DOI]

-

90. Galdiero F, Bentivoglio C, Nuzzo I, Ianniello R, Capasso C, Mattera S, et al. Effects of benzodiazepines on immunodeficiency and resistance in mice. Life Sci. 1995;57(26):2413-2423.[DOI]

-

91. Huemer HP, Lassnig C, Nowotny N, Irschick EU, Kitchen M, Pavlic M. Diazepam leads to enhanced severity of orthopoxvirus infection and immune suppression. Vaccine. 2010;28(38):6152-6158.[DOI]

-

92. Sanders RD, Godlee A, Fujimori T, Goulding J, Xin G, Salek-Ardakani S, et al. Benzodiazepine augmented γ-amino-butyric acid signaling increases mortality from pneumonia in mice. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(7):1627-1636.[DOI]

-

93. Parsaik AK, Mascarenhas SS, Khosh-Chashm D, Hashmi A, John V, Okusaga O, et al. Mortality associated with anxiolytic and hypnotic drugs—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2016;50(6):520-533.[DOI]

-

94. Woods A, Begum M, Gonzalez-Chica D, Bernardo C, Hoon E, Stocks N. Long-term benzodiazepines and z-drug prescribing in australian general practice between 2011 and 2018: A national study.Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2022;10(1):e00896.[DOI]

-

95. Soyombo S, Stanbrook R, Aujla H, Capewell D, Shantikumar M, Kidy F, et al. Socioeconomic status and benzodiazepine and z-drug prescribing: A cross-sectional study of practice-level data in england. Fam Pract. 2020;37(2):194-199.[DOI]

-

96. Quigley P, Usher C, Bennett K, Feely J. Socioeconomic influences on benzodiazepine consumption in an irish region. Eur Addict Res. 2006;12(3):145-150.[DOI]

-

97. Lesén E, Andersson K, Petzold M, Carlsten A. Socioeconomic determinants of psychotropic drug utilisation among elderly: A national population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):118.[DOI]

-

98. Yang HK, Simoni-Wastila L, Zuckerman IH, Stuart B. Benzodiazepine use and expenditures for medicare beneficiaries and the implications of medicare part d exclusions. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(4):384-391.[DOI]

-

99. Aasmets O, Taba N, Krigul KL, Andreson R, Org E. A hidden confounder for microbiome studies: Medications used years before sample collection. mSystems. 2025;10(10):e00541-00525.[DOI]

-

100. Alvarez-Valadez K, Sauvat A, Diharce J, Leduc M, Stoll G, Guittat L, et al. Lysosomal damage due to cholesterol accumulation triggers immunogenic cell death. Autophagy. 2025;21(5):934-956.[DOI]

-

101. Li B, Elsten-Brown J, Li M, Zhu E, Li Z, Chen Y, et al. Serotonin transporter inhibits antitumor immunity through regulating the intratumoral serotonin axis. Cell. 2025;188(14):3823-3842.e3821.[DOI]

-

102. Alvarez-Valadez K, Kroemer G, Djavaheri-Mergny M. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors enhance cancer immunosurveillance by pleiotropic mechanisms. OncoImmunology. 2025;14(1):2564734.[DOI]

-

103. Zhao L, Liu P, Sauvat A, Le Provost KC, Liu J, Checcoli A, et al. Dexmedetomidine induces immunogenic cancer cell death and sensitizes tumors to PD-1 blockade. J Immunother Cancer. 2025;13(6):e010714.[DOI]

-

104. Hernádfői MV, Koch DK, Kói T, Imrei M, Nagy R, Máté V, et al. Burden of childhood cancer and the social and economic challenges in adulthood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2024;178(6):548-566.[DOI]

-

105. Montégut L, López-Otín C, Kroemer G. Aging and cancer. Mol Cancer. 2024;23(1):106.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite