Abstract

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a risk factor for many aging-related medical conditions as well as cognitive decline and mortality. These and other types of observations indicate a premature aging phenotype associated with the conditions mentioned above. Recent studies have started to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the link between MDD and premature aging, pointing towards novel treatments of this phenotype. In this review, we first present evidence linking MDD to a premature aging phenotype and its association with abnormalities in multiple hallmarks of biological aging. Next, we discuss implications for treatment in MDD, including the potential geroprotective effects of antidepressant treatment as well as the conceptualization of biological aging processes as targets for novel gerotherapeutic interventions. Finally, we highlight the importance of integrating mental health assessment into both research and clinical settings to fulfill the promises of the new medical discipline of Geromedicine in preventing age-related decline and extending healthspan in the aging population.

Keywords

1. Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is one of the most common mental disorders across the lifespan. Its prevalence varies across populations, with recent estimates indicated that the 12-month and lifetime prevalence rates were 10.4% and 20.6%, respectively[1]. MDD also ranks among the five most disabling disorders worldwide, and it is one of the fewest non-communicable diseases that has consistently shown an increase in the disability-adjusted life years in recent decades[2,3]. Beyond its psychological and functional impact, growing evidence suggests that MDD may exert systemic biological effects which resemble or accelerate the aspects of the aging process[4,5]. In this perspective, we summarize evidence suggesting that MDD, across the lifespan, is associated with a premature aging phenotype. Then, we summarize the potential biological mechanisms underlying these associations, and we explore how the emerging field of Geromedicine – an emerging medical discipline focused on enhancing healthspan by targeting biological aging pathways consistent with geroscience – may help reduce the burden of this condition.

2. MDD and Premature Aging Phenotype: The Clinical-Epidemiological Evidence

MDD has been conceptualized as both a psychological disorder, contributed to life stressors such as trauma and poverty, and as a brain disorder stemming from dysregulated neuronal circuits[6,7]. As only a brain and psychological syndrome, it would be expected to have a limited impact on peripheral organs and systems. However, mounting clinical and epidemiological evidence suggests that MDD is associated with declining general health, and it is a major, independent risk factor for multiple chronic medical conditions[8-11]. This relationship persists even after the full remission of the depressive episode. Such associations are present across the lifespan but are stronger among older adults.

For example, MDD has been associated with severe cardiometabolic dysfunction and obesity, which are independent of the severity of depressive symptoms[12]. Individuals with MDD show decreased heart rate variability[13], a marker of autonomic imbalance and a predictor of poor cardiovascular outcomes. Sleep abnormality is also common among individuals with MDD, who most commonly complain of insomnia and show polysomnographic evidence of shortened REM sleep latency, increased rapid eye movement (REM) sleep duration and density, and reduced slow-wave sleep[14].

In addition to its impact on general health markers, MDD has also been associated with the decline in multiple age-related functional parameters. Cognitive impairment, in particular like executive dysfunction, episodic memory impairment, and attentional deficits, is common during acute depressive episode, particularly among older adults[15,16]. Even after the successful treatment of the depressive episode, a subset of individuals with MDD show persistent cognitive impairment[17], which may be an early indicator of increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia (ADRD) in this population[18]. The mechanisms of cognitive impairment and decline in MDD may be independent of the pathophysiological mechanisms of ADRD, suggesting that abnormalities in processes closely linked to biological aging acceleration may play a major role in explaining these associations[19].

Gait is a complex neuromechanical process that involves the coordination of multiple neurological, muscular processes, and somatosensory integration[20]. Slow gait speed is a common feature of pathological aging and a major risk factor for adverse health outcomes, including higher mortality risk[21]. Recent studies have shown that MDD, especially among older adults, is associated with a significant decline in gait speed[22]. Such associations were independent of the severity of the depressive episode, medical comorbidity, and psychomotor retardation, which is a common depressive symptom. Although the impact of the association between MDD and slow gait is unclear, it is possible that both conditions may have synergistic effects on biological aging processes, such as inflammation and mitochondrial dysfunction, explaining the higher risks of adverse health outcomes of their comorbidity than either condition alone.

Additional epidemiological evidence demonstrates that MDD substantially increases the risk of adverse health outcomes. MDD has been associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular, cerebrovascular disease, and cardiometabolic disorders like type 2 diabetes[23,24]. More recently, MDD has been linked with a higher incidence of phenotypic frailty syndrome[25]. Of particular interest, a subset of individuals may present with frailty, MDD and cognitive impairment, a condition named “triad of impairment”[26]. Finally, MDD increases the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular-related mortality, a process probably mediated by accelerated vascular aging[23,27,28].

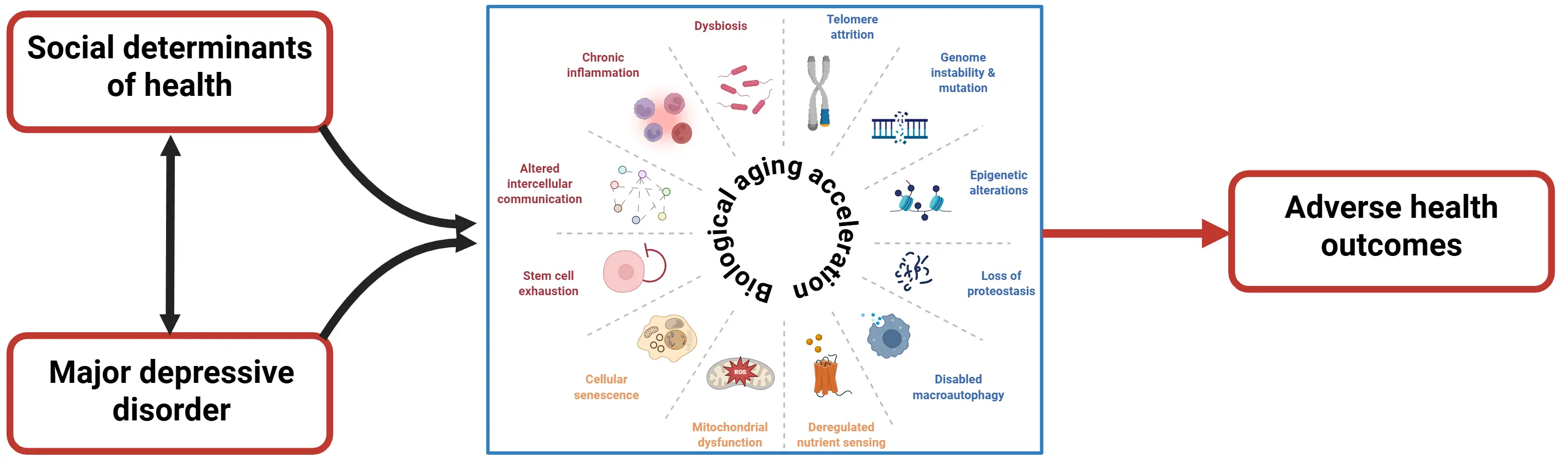

It is noteworthy that these features which were discussed above are commonly associated with advanced chronological aging, suggesting that individuals with MDD present with, or are at higher risk for, a premature aging phenotype (Figure 1).

Figure 1. MDD and SDH are closely related phenomena, showing a bidirectional relationship. They have both independent and synergistic effects on multiple hallmarks of biological aging, contributing to accelerated biological aging observed in these individuals. In turn, the accelerated biological aging can be one of the mechanisms that explains the higher incidence of adverse health outcomes (e.g., medical multimorbidity, and premature mortality) that are associated with both MDD and worse SDH in the general population. MDD: major depressive disorders; SDH: social determinants of health.

3. MDD and Premature Aging Phenotype: Putative Mechanisms

A growing body of evidence has revealed significant abnormalities across multiple hallmarks of biological aging in MDD, providing mechanistic explanations for its link with premature aging phenotypes[4]. One of the earliest findings from clinical and epidemiological studies shows both significant leukocyte telomere attrition in these individuals[29,30] as well as the association between greater telomere attrition and the severity, chronicity, and recurrence of depressive episodes[31]. Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain this relationship. Chronic psychological stress and resulting hyperactivation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis in some patients with MDD lead to elevated glucocorticoid levels, oxidative stress, and increased inflammatory activity—which accelerate telomere attrition. In parallel, reduced telomerase activity observed in some patients with MDD may limit the cell’s ability to counteract telomere shortening. Together, these mechanisms could lead to cumulative telomere damage over time.

A large amount of evidence indicates that MDD is associated with a significant increase in inflammatory cytokines, impaired compensatory anti-inflammatory response, and alterations in the cellular composition of the immune system. For example, meta-analyses have shown a significant increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines, mainly IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α[32]. Such abnormalities are particularly significant among older adults with MDD[33], and they are associated with the severity of cognitive impairment[34]. Successful antidepressant treatment can at least partially decrease levels of inflammatory cytokines, and in individuals with a higher inflammatory burden, as measured by C-reactive protein levels, adjunctive anti-inflammatory medications can accelerate antidepressant response[35,36]. Also, individuals with MDD might present with impaired immunogenicity, which is manifested by greater vulnerability to viral infection and impaired vaccine response[37-39]. In general, the pattern of immune-inflammatory abnormalities in MDD resembles “inflammaging” ̶ the chronic, low-grade, systemic inflammation with advancing age, which is described as one of the hallmarks of biological aging[40].

Mitochondrial dysfunction, another hallmark of biological aging, has also been described in MDD. The first evidence demonstrating mitochondrial dysfunction in MDD came from studies showing a significant increase in oxidative markers[41], and an imbalance between oxidative and anti-oxidative stress markers in these individuals[42]. More recently, evidence of mitochondrial dysfunction in MDD comes from studies showing a significant increase in the levels of circulating cell-free mitochondrial DNA (ccf-mtDNA)[43], and reduced mitochondrial DNA integrity in these individuals[44]. Furthermore, high ccf-mtDNA levels predicted elevated inflammatory burden in MDD, highlighting the complex interrelationship between biological aging processes[44].

The accumulation of senescent cells in tissues and organs is one of the most robust hallmarks of biological aging and a strong predictor of multiple age-associated medical conditions[45]. There is growing evidence suggesting the association between cellular senescence burden and MDD across the lifespan. For example, individuals with MDD show significantly higher levels of markers related to the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP)[46]. A higher SASP level has been associated with the severity of depressive episode, medical comorbidity burden, severity of cognitive impairment, and structural markers of brain deterioration in both white and gray matter[47-50]. Moreover, a higher SASP is a strong predictor of poor antidepressant response among older adults[51]. Finally, older adults with MDD exhibit accumulation of senescent CD4+ and monocyte cells, which correlate with abnormal expression of multiple proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines[52].

Studies evaluating biological aging clocks provide additional evidence of the association between MDD and premature biological aging. Individuals with MDD show evidence of biological aging acceleration based on two biological aging clocks derived from clinical lab test results, the BioAge and the PhenoAge[53]. What’s more, greater BioAge and PhenoAge were associated with a higher risk of incident MDD over an 8.7-year follow-up period. Similar findings were observed using recently developed biological aging clocks based on proteomic measures[54,55]. In this study, individuals with MDD shows greater biological aging acceleration both at systemic and brain-specific levels[56]. Moreover, the remission of depressive episodes is associated with improvement in biological aging markers at a systemic level; however, brain-specific proteomic biological aging remains significantly elevated in remitted individuals compared to never-depressed individuals, suggesting that a major depressive episode may have a persistent, long-lasting negative effect on brain aging markers. Finally, biological aging acceleration in MDD is a strong predictor of ADRD incidence or mortality in these individuals. Additionally, studies focusing on DNA methylation-based biological aging clocks have shown a significantly greater epigenetics aging and a faster pace of aging compared to control subjects[57,58].

Other hallmarks of biological aging have also been implicated in MDD. For example, individuals with MDD show strong evidence of insulin resistance[59], implicating abnormalities nutrient sensing control in the MDD physiopathology. These findings also help explain the strong, bidirectional association between MDD and metabolic disorders such as obesity and diabetes[60,61]. There is less evidence linking proteostasis and autophagy abnormalities in human studies, but the proteomic-based studies have shown an association between identified biological pathways related to proteostasis dysregulation (e.g., unfolded protein response, impaired mitophagy) and MDD in young and older adult[34,62]. Gut dysbiosis has been implicated in the physiopathology of MDD[63], and the abnormality patterns resemble the ones observed during pathological aging (i.e., increased Bacteroidetes and decreased Firmicutes levels, favoring pro-inflammatory bacteria over anti-inflammatory, and butyrate-producing bacteria)[64]. Finally, other studies identified abnormalities in other hallmarks of biological aging in MDD, i.e., genomic instability[65] and stem cell exhaustion[66]. However, this evidence is based on small case-control studies and needs to be replicated in larger cohorts.

Overall, these findings of abnormalities across multiple hallmarks of biological aging provide a strong mechanistic explanation for the clinical and epidemiological association between MDD and premature aging.

4. Intersection Between Social Determinants of Health and Major Depression and Its Impact on Biological Aging

There is a well-established, intimate association between social determinants of health (SDH), in particular low socio-economic status, chronic stress, trauma history, and MDD[67]. On the other hand, multiple recent studies have also shown that SDH affects biological aging[68]. For example, chronic stress and exposure to traumatic events have been associated with abnormalities in the inflammatory response, particularly the elevation of pro-inflammatory cytokines[69]. Such changes are mediated in part by chronic activation of the HPA axis and an imbalance in the autonomic nervous system response[70]. In addition, chronic stress can lead to telomere attrition, mitochondrial dysfunction, triggering of DNA damage response, and epigenetic changes, all of which are commonly associated with accelerated biological aging[71,72]. Other SDH, such as social isolation, low socio-economic status, and living in disadvantaged neighborhoods, have also been associated with abnormal inflammatory responses[73], abnormal intercellular communication[74], and accelerated biological aging[75,76]. Therefore, it is plausible to hypothesize that the association between MDD and accelerated biological aging is partially mediated by the multiple SDH commonly observed in this population.

5. Biological Aging as a Therapeutic Target for MDD

The evidence connecting biological aging with MDD raises the question of whether targeting the hallmarks of accelerated biological aging could be beneficial in its management. Antidepressants, such as the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs, e.g., fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, citalopram, and escitalopram), are the mainstream drugs in the management of MDD. Prior studies have found that these drugs can reduce oxidative stress[77], and these drugs have anti-inflammatory effects[78]. Recent research has shown that fluvoxamine, an SSRI which is also a sigma-1 agonist, can be neuroprotective under conditions of neuroinflammation[79]. However, it is not clear if antidepressants can improve age-related outcomes such as reduced risk of dementia and mortality[80,81]. Lithium, a mood stabilizing agent used in more severe and treatment-resistant cases of depression, enhances neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity and it has geroprotective effects with respect to telomere attrition, inflammatory, cellular senescence burden, and mitochondrial function[82-85]. It is noteworthy that long-term lithium exposure is associated with reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease, mortality in clinical populations and in epidemiological studies of chronic passive exposure via drinking water[86-88].

The evidence of the association between the accumulation of senescent cells and treatment response in MDD suggests that senolytic therapies could improve depressive symptoms that overlap with accelerated cellular aging in the brain. Along these lines, a recent study identified 13 drugs, which are known to slow the pace of brain aging that also modulate molecular pathways linked to pathophysiology of depression[89]. Among these drugs, dasatinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor approved to use in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ALL), is currently under investigation for the management of treatment-resistant depression and other serious mental illnesses among older adults[90,91]. Quercetin, an antioxidant found in fruits and vegetables, exerts pro-apoptotic effects through inhibition of the phosphatidylinositide-3-kinase (PI3K) and protein kinase B (PKB) pathways. Combination therapies like dasatinib/quercetin target multiple, interconnected cellular hallmarks of aging simultaneously, and they are also being studied in older adults with treatment-resistant depression[91]. Overall, the available evidence indicates that existing drugs used to manage MDD may have geroprotective effects, and conversely, geroscience-guided interventions may modulate distinct hallmarks of biological aging and thereby provide benefits to individuals with MDD.

Non-pharmacological interventions, such as psychotherapy and lifestyle interventions that optimize physical activity, nutrition, and sleep hygiene, are commonly recommended in combination with antidepressant therapy to reduce the overall burden of depressive symptoms[92]. Emerging evidence suggests they can also have geroprotective effects. For example, cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia is commonly used to improve sleep patterns in MDD, and a recent study suggests that it can reduce the cellular senescence burden in older adults[93]. Dietary interventions and physical activity are commonly recommended as part of the management of MDD. They modulate multiple hallmarks of biological aging by reducing insulin resistance, improving mitochondrial function, and pro-inflammatory burden[94], suggesting that their benefits for MDD may, in part, be due to their effects on these biological processes. Meditation, mindfulness-based stress reduction techniques, and psychotherapy are also part of the therapeutic armamentarium against MDD. Notably, these interventions have also shown to improve inflammatory response and lower biological aging acceleration based on epigenetics clocks[95-98].

Additional studies are necessary to confirm the potential benefits of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions on modulating biological aging processes in individuals with MDD or in the general population without a diagnosis of MDD. In addition, the complexity of both MDD pathophysiology and biological aging processes calls for a multi-pronged approach combining pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions achieve optimal effects in managing MDD, slowing the pace of biological aging, and improving long-term health outcomes in these individuals.

6. Future Directions

The emerging field of Geromedicine aims to optimize health and prevent disease in human beings across the lifespan by targeting their underlying aging processes, through pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches[99]. Such an approach has the potential not only to prevent many chronic medical conditions but also to extend an individual’s healthspan considerably. For this approach to benefit the maximum number of people, we need to integrate careful assessment of mental health conditions and social determinants of health[68] into the Geromedicine armamentarium. As noted above, MDD (and possibly other serious medical conditions such as bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and post-traumatic stress disorder) is associated with a premature aging phenotype and significant abnormalities in multiple hallmarks of biological aging and biological aging acceleration. Moreover, their successful treatments can at least partially restore these biological abnormalities and reduce the risk of adverse health outcomes associated with them.

Given the high prevalence of MDD and other serious mental illnesses across the lifespan, their assessment, recognition, and correct management should be an integral part of the Geromedicine effort, both in research and clinical settings. Neglecting the issue risks undermining the promise of Geromedicine to prevent chronic diseases and extend healthspan in the general population in an equitable manner. Therefore, we propose to incorporate the following steps into Geromedicine research and clinical practice. Firstly, we recommend including screening instruments for the most common mental health conditions and social determinants of health. These instruments are generally short, self-reported, and they do not require specific training for administration. Table 1 provides some examples of commonly used screening instruments in mental health research and clinical settings. Secondly, we recommend the proactive management of any mental health conditions. This goal can be achieved by providing better training for members of the patient management team to recognize and treat mental health conditions, and by integrating mental health professionals into the team. Last but not least, we need to accelerate basic, translational, and clinical research to better understand how MDD and other serious mental illnesses can affect biological aging processes, their long-term impact on health trajectories, and to identify novel treatment targets for these conditions. This goal could be achieved through multiple strategies, such as examining the effects on both aging biology and the longitudinal course of illness in MDD; testing Geromedicine interventions specifically for people with MDD; or having a greater focus on aging biology in clinical trials for mental illnesses – especially those at high risk for accelerated aging like treatment-resistant depression, schizophrenia, PTSD, and people with chronic psychosocial adversity.

| Instrument | Purpose |

| PHQ - 9 | Screening for depressive symptoms |

| CES-D - 20 | Screening for depressive symptoms |

| GAD-7 | Screening for anxiety symptoms |

| PCL-5 | Screening for post-traumatic stress disorder |

| Mood disorder questionnaire | Screening for bipolar disorder |

| UCLA loneliness scale v.2 | Assessment of loneliness |

| PROMIS Social isolation short form | Assessment of social isolation |

| Perceived Stress Scale | Assessment of perceived stress |

| Lubben Social Network Scale | Assessment of social network and isolation |

| AHC-HRSN | Assessment of social needs |

| SINCERE | Assessment of social needs |

PHQ: physical health questionnaire; CES-D: center for epidemiologic studies depression scale; GAD: generalized anxiety disorder; AHC-HRSN: accountable health communities health-related social needs; SINCERE: screener for intensifying community referrals for health; PCL-5: PTSD Checklist for DSM-5.

Authors contribution

Diniz BS, Nicol GE, Lenze EJ: Conceptualization, writing-original draft.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

None.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

References

-

1. Hasin DS, Sarvet AL, Meyers JL, Saha TD, Ruan WJ, Stohl M, et al. Epidemiology of adult DSM-5 major depressive disorder and its specifiers in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(4):336.[DOI]

-

3. Hay SI, Ong KL, Santomauro DF, Bhoomadevi A, Aalipour MA, Aalruz H, et al. Burden of 375 diseases and injuries, risk-attributable burden of 88 risk factors, and healthy life expectancy in 204 countries and territories, including 660 subnational locations, 1990–2023: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2023. Lancet. 2025;406(10513):1873-1922.[DOI]

-

4. Lorenzo EC, Kuchel GA, Kuo CL, Moffitt TE, Diniz BS. Major depression and the biological hallmarks of aging. Ageing Res Rev. 2023;83:101805.[DOI]

-

7. Kendler KS. The origin of our modern concept of depression: The history of melancholia from 1780-1880: A review. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(8):863.[DOI]

-

8. Halstead S, Cao C, Høgnason Mohr G, Ebdrup BH, Pillinger T, McCutcheon RA, et al. Prevalence of multimorbidity in people with and without severe mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2024;11(6):431-442.[DOI]

-

9. Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(4):334.[DOI]

-

10. Chan JKN, Correll CU, Wong CSM, Chu RST, Fung VSC, Wong GHS, et al. Life expectancy and years of potential life lost in people with mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine. 2023;65:102294.[DOI]

-

11. Diniz BS, Butters MA, Albert SM, Dew MA, Reynolds CF. Late-life depression and risk of vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based cohort studies. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202(5):329-335.[DOI]

-

12. Penninx BWJH, Lange SMM. Metabolic syndrome in psychiatric patients: Overview, mechanisms, and implications. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2018;20(1):63-73.[DOI]

-

14. Leitner C, Dalle Piagge F, Tomic T, Nozza F, Fasiello E, Castronovo V, et al. Sleep alterations in major depressive disorder and insomnia disorder: A network meta-analysis of polysomnographic studies. Sleep Med Rev. 2025;80:102048.[DOI]

-

15. Rock PL, Roiser JP, Riedel WJ, Blackwell AD. Cognitive impairment in depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2014;44(10):2029-2040.[DOI]

-

17. Semkovska M, Quinlivan L, O’Grady T, Johnson R, Collins A, O’Connor J, et al. Cognitive function following a major depressive episode: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(10):851-861.[DOI]

-

21. Studenski S. Gait speed and survival in older adults. JAMA. 2011;305(1):50.[DOI]

-

23. Leung YW, Flora DB, Gravely S, Irvine J, Carney RM, Grace SL. The impact of premorbid and postmorbid depression onset on mortality and cardiac morbidity among patients with coronary heart disease: Meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2012;74(8):786-801.[DOI]

-

24. Richmond-Rakerd LS, D’Souza S, Milne BJ, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. Longitudinal associations of mental disorders with physical diseases and mortality among 2.3 million New Zealand citizens. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2033448.[DOI]

-

25. Soysal P, Veronese N, Thompson T, Kahl KG, Fernandes BS, Prina AM, et al. Relationship between depression and frailty in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2017;36:78-87.[DOI]

-

27. Diniz BS, Reynolds CF III, Butters MA, Dew MA, Firmo JOA, Lima-Costa MF, et al. The effect of gender, age, and symptom severity in late-life depression on the risk of all-cause mortality: The bambuí cohort study of aging: Effect of Late-Life Depression on the Mortality Risk. Depress Anxiety. 2014;31(9):787-795.[DOI]

-

28. Feng YT, Pei JY, Wang YP, Feng XF. Association between depression and vascular aging: A comprehensive analysis of predictive value and mortality risks. J Affect Disord. 2024;367:632-639.[DOI]

-

33. Diniz BS, Lin CW, Sibille E, Tseng G, Lotrich F, Aizenstein HJ, et al. Circulating biosignatures of late-life depression (LLD): Towards a comprehensive, data-driven approach to understanding LLD pathophysiology. J Psychiatr Res. 2016;82:1-7.[DOI]

-

34. Diniz BS, Sibille E, Ding Y, Tseng G, Aizenstein HJ, Lotrich F, et al. Plasma biosignature and brain pathology related to persistent cognitive impairment in late-life depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20(5):594-601.[DOI]

-

35. Gasparini A, Callegari C, Lucca G, Bellini A, Caselli I, Ielmini M. Inflammatory biomarker and response to antidepressant in major depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2025;52(1):36-52.[DOI]

-

36. Nettis MA, Lombardo G, Hastings C, Zajkowska Z, Mariani N, Nikkheslat N, et al. Augmentation therapy with minocycline in treatment-resistant depression patients with low-grade peripheral inflammation: Results from a double-blind randomised clinical trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2021;46:939-948.[DOI]

-

37. Ford BN, Savitz J. Depression, aging, and immunity: Implications for COVID-19 vaccine immunogenicity. Immun Ageing. 2022;19(1):32.[DOI]

-

38. Irwin MR, Levin MJ, Laudenslager ML, Olmstead R, Lucko A, Lang N, et al. Varicella zoster virus-specific immune responses to a herpes zoster vaccine in elderly recipients with major depression and the impact of antidepressant medications. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(8):1085-1093.[DOI]

-

39. Elpers H, Teismann H, Wellmann J, Berger K, Karch A, Rübsamen N. Major depressive disorders increase the susceptibility to self-reported infections in two German cohort studies. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2023;58(2):277-286.[DOI]

-

41. Black CN, Bot M, Scheffer PG, Cuijpers P, Penninx BWJH. Is depression associated with increased oxidative stress? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;51:164-175.[DOI]

-

42. Diniz BS, Mendes-Silva AP, Silva LB, Bertola L, Vieira MC, Ferreira JD, et al. Oxidative stress markers imbalance in late-life depression. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;102:29-33.[DOI]

-

43. Gonçalves VF, Mendes-Silva AP, Koyama E, Vieira E, Kennedy JL, Diniz B. Increased levels of circulating cell-free mtDNA in plasma of late life depression subjects. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;139:25-29.[DOI]

-

44. Mendes-Silva AP, El-Ahmad P, Costa AP, Balbuena LC, Nikolova YS, Rajji T, et al. Decreased mitochondrial DNA integrity and elevated inflammatory markers in late-life depression: A longitudinal study. Biol Psychiatry Glob Open Sci. 2025;5(6):100598.[DOI]

-

46. Diniz BS, Reynolds CF III, Sibille E, Lin CW, Tseng G, Lotrich F, et al. Enhanced molecular aging in late-life depression: The senescent-associated secretory phenotype. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;25(1):64-72.[DOI]

-

47. Seitz-Holland J, Mulsant BH, Reynolds III CF, Blumberger DM, Karp JF, Butters MA, et al. Major depression, physical health and molecular senescence markers abnormalities. Nat Ment Health. 2023;1:200-209.[DOI]

-

48. Diniz BS, Vieira EM, Mendes-Silva AP, Bowie CR, Butters MA, Fischer CE, et al. Mild cognitive impairment and major depressive disorder are associated with molecular senescence abnormalities in older adults. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;7:e12129.[DOI]

-

49. Mendes-Silva AP, Mwangi B, Aizenstein H, Reynolds CF III, Butters MA, Diniz BS. Molecular senescence is associated with white matter microstructural damage in late-life depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;27(12):1414-1418.[DOI]

-

50. Diniz BS, Reynolds CF, Sibille E, Bot M, Penninx BWJH. Major depression and enhanced molecular senescence abnormalities in young and middle-aged adults. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9:198.[DOI]

-

51. Diniz BS, Mulsant BH, Reynolds CF III, Blumberger DM, Karp JF, Butters MA, et al. Association of molecular senescence markers in late-life depression with clinical characteristics and treatment outcome. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(6):e2219678.[DOI]

-

52. Lorenzo EC, Figueroa JE, Demirci DA, El-Tayyeb F, Huggins BJ, Illindala M, et al. Unraveling the association between major depressive disorder and senescent biomarkers in immune cells of older adults: A single-cell phenotypic analysis. Front Aging. 2024;5:1376086.[DOI]

-

54. Kuo CL, Liu P, Drouard G, Vuoksimaa E, Kaprio J, Ollikainen M, et al. A proteomic signature of healthspan. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2025;122(23):e2414086122.[DOI]

-

55. Kuo CL, Chen Z, Liu P, Pilling LC, Atkins JL, Fortinsky RH, et al. Proteomic aging clock (PAC) predicts age-related outcomes in middle-aged and older adults. Aging Cell. 2024;23(8):e14195.[DOI]

-

56. Diniz BS, Zhao S, Drouard G, Vuoksimaa E, Ollikainen M, Lenze EJ, et al. Biological aging acceleration in major depressive disorder: A multi-omics analysis. Aging Cell. 2026;25:e70310.[DOI]

-

57. Han LKM, Aghajani M, Clark SL, Chan RF, Hattab MW, Shabalin AA, et al. Epigenetic aging in major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):774-782.[DOI]

-

58. Wertz J, Caspi A, Ambler A, Broadbent J, Hancox RJ, Harrington H, et al. Association of history of psychopathology with accelerated aging at midlife. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(5):530.[DOI]

-

59. Kan C, Silva N, Golden SH, Rajala U, Timonen M, Stahl D, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between depression and insulin resistance. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(2):480-489.[DOI]

-

65. Śliwiński T. Elevated level of DNA damage and impaired repair of oxidative DNA damage in patients with recurrent depressive disorder. Med Sci Monit. 2015;21:412-418.[DOI]

-

67. Alon N, Macrynikola N, Jester DJ, Keshavan M, Reynolds CF III, Saxena S, et al. Social determinants of mental health in major depressive disorder: Umbrella review of 26 meta-analyses and systematic reviews. Psychiatry Res. 2024;335:115854.[DOI]

-

68. López-Otín C, Kroemer G. Hallmarks of aging: Integrating molecular and social determinants. Geromedicine. 2025;1.[DOI]

-

69. Hansen JL, Carroll JE, Seeman TE, Cole SW, Rentscher KE. Lifetime chronic stress exposures, stress hormones, and biological aging: Results from the Midlife in the United States (MIDUS) study. Brain Behav Immun. 2025;123:1159-1168.[DOI]

-

70. Bourassa KJ, Sbarra DA. Trauma, adversity, and biological aging: Behavioral mechanisms relevant to treatment and theory. Transl Psychiatry. 2024;14:285.[DOI]

-

71. Polsky LR, Rentscher KE, Carroll JE. Stress-induced biological aging: A review and guide for research priorities. Brain Behav Immun. 2022;104:97-109.[DOI]

-

72. Epel ES, Prather AA. Stress, telomeres, and psychopathology: Toward a deeper understanding of a triad of early aging. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2018;14:371-397.[DOI]

-

73. Matthews T, Rasmussen LJH, Ambler A, Danese A, Eugen-Olsen J, Fancourt D, et al. Social isolation, loneliness, and inflammation: A multi-cohort investigation in early and mid-adulthood. Brain Behav Immun. 2024;115:727-736.[DOI]

-

74. Shen C, Zhang R, Yu J, Sahakian BJ, Cheng W, Feng J. Plasma proteomic signatures of social isolation and loneliness associated with morbidity and mortality. Nat Hum Behav. 2025;9(3):569-583.[DOI]

-

75. Kivimäki M, Pentti J, Frank P, Liu F, Blake A, Nyberg ST, et al. Social disadvantage accelerates aging. Nat Med. 2025;31(5):1635-1643.[DOI]

-

76. Li J, Li J, Xu X, Shen W, Sun Y, Fu Y, et al. Social determinants of health, accelerated biological aging, and long-term health outcomes. Nat Commun. 2026;17:900.[DOI]

-

77. Liu T, Zhong S, Liao X, Chen J, He T, Lai S, et al. A meta-analysis of oxidative stress markers in depression. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0138904.[DOI]

-

78. Köhler CA, Freitas TH, Stubbs B, Maes M, Solmi M, Veronese N, et al. Peripheral alterations in cytokine and chemokine levels after antidepressant drug treatment for major depressive disorder: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55(5):4195-4206.[DOI]

-

81. Gallo JJ, Morales KH, Bogner HR, Raue PJ, Zee J, Bruce ML, et al. Long term effect of depression care management on mortality in older adults: Follow-up of cluster randomized clinical trial in primary care. BMJ. 2013;346(jun05 2):f2570.[DOI]

-

82. Queissner R, Lenger M, Birner A, Dalkner N, Fellendorf F, Bengesser S, et al. The association between anti-inflammatory effects of long-term lithium treatment and illness course in Bipolar Disorder. J Affect Disord. 2021;281:228-234.[DOI]

-

83. Machado-Vieira R, Zanetti MV, Teixeira AL, Uno M, Valiengo LL, Soeiro-de-Souza MG, et al. Decreased AKT1/mTOR pathway mRNA expression in short-term bipolar disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;25(4):468-473.[DOI]

-

85. Viel T, Chinta S, Rane A, Chamoli M, Buck H, Andersen J. Microdose lithium reduces cellular senescence in human astrocytes - a potential pharmacotherapy for COVID-19? Aging. 2020;12(11):10035-10040.[DOI]

-

86. Kessing LV, Gerds TA, Knudsen NN, Jørgensen LF, Kristiansen SM, Voutchkova D, et al. Association of lithium in drinking water with the incidence of dementia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(10):1005.[DOI]

-

87. Kessing LV, Søndergård L, Forman JL, Andersen PK. Lithium treatment and risk of dementia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(11):1331.[DOI]

-

88. Chan JKN, Wong CSM, Fang CZ, Hung SC, Lo HKY, Chang WC. Mortality risk and mood stabilizers in bipolar disorder: A propensity-score-weighted population-based cohort study in 2002-2018. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2024;33:e31.[DOI]

-

89. Yi F, Yuan J, Somekh J, Peleg M, Zhu YC, Jia Z, et al. Genetically supported targets and drug repurposing for brain aging: A systematic study in the UK Biobank. Sci Adv. 2025;11(11):eadr3757.[DOI]

-

90. Riessland M, Ximerakis M, Jarjour AA, Zhang B, Orr ME. Therapeutic targeting of senescent cells in the CNS. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2024;23(11):817-837.[DOI]

-

91. Schweiger A, Diniz B, Nicol G, Schweiger J, Dasklakis-Perez AE, Lenze EJ. Protocol for a pilot clinical trial of the senolytic drug combination Dasatinib Plus Quercetin to mitigate age-related health and cognitive decline in mental disorders. F1000Research. 2025;13:1072.[DOI]

-

92. Lam RW, Kennedy SH, Adams C, Bahji A, Beaulieu S, Bhat V, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2023 Update on Clinical Guidelines for Management of Major Depressive Disorder in Adults: Réseau canadien pour les traitements de l’humeur et de l’anxiété (CANMAT) 2023: Mise à jour des lignes directrices cliniques pour la prise en charge du trouble dépressif majeur chez les adultes. Can J Psychiatry. 2024;69(9):641-687.[DOI]

-

93. Carroll JE, Olmstead R, Cole SW, Breen EC, Arevalo JM, Irwin MR. Remission of insomnia in older adults treated with cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) reduces p16INK4a gene expression in peripheral blood: Secondary outcome analysis from a randomized clinical trial. GeroScience. 2023;45(4):2325-2335.[DOI]

-

95. Black DS, Slavich GM. Mindfulness meditation and the immune system: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2016;1373(1):13-24.[DOI]

-

96. Chaix R, Alvarez-López MJ, Fagny M, Lemee L, Regnault B, Davidson RJ, et al. Epigenetic clock analysis in long-term meditators. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017;85:210-214.[DOI]

-

98. Ensink JBM, Henneman P, Venema A, Zantvoord JB, den Kelder RO, Mannens MMAM, et al. Distinct saliva DNA methylation profiles in relation to treatment outcome in youth with posttraumatic stress disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2024;14:309.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite