Abstract

Background: The outcomes of older adults with cancer are usually worse than those of their younger counterparts. Several randomised trials have demonstrated benefits of a comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) in older patients undergoing systemic cancer therapy. Despite that, CGA is not implemented into routine care in Germany and data on its efficacy and feasibility within the German healthcare system are missing.

Methods: This prospective, bicentric cohort study will assess the feasibility of CGA implementation into routine care for older adults with cancer in Germany. Patients ≥ 65 years with a positive geriatric screening (G8) and newly diagnosed cancer or progressive disease prior to a new treatment line undergo a CGA as part of their routine care. Patients who consent to participate in the study receive a follow-up call after three months to assess functional measures, and their (routine) CGA data are analyzed thereafter. CGA results are presented during the multidisciplinary team meeting to inform treatment recommendations provided by primary healthcare providers (pHCP; e.g., oncologists, gynecologists, urologists). pHCP are further evaluated for their satisfaction with CGA implementation and whether its results have influenced their recommendations. The primary endpoint is to estimate the patients’ willingness to participate with an accuracy of ± 7.5%. Secondary endpoints focus on additional feasibility measures and patient preferences.

Conclusion: This study will assess the feasibility of CGA implementation into routine care for older cancer patients. Its results will provide the framework to design a larger subsequent trial to assess the efficacy and cost effectiveness of CGA implementation in Germany.

Clinical trial registration number: DRKS00035569

Keywords

1. Introduction

1.1 Background

Patients ≥ 65 years accounted for approximately 65% of all adult cancer cases in Germany in 2022[1]. The outcomes of older adults with cancer are usually worse than those of their younger counterparts, largely due to additional comorbidities and frailty complicating treatment tolerability[2]. To avoid under- and overtreatment, a comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA), which provides an objective view on the functional and psychosocial capacities of the older cancer patient, needs to be integrated into decision-making across all oncological disciplines[3,4]. Recently, the use of CGA has been shown to decrease the rate of treatment-related toxicities in older adults receiving systemic cancer therapy[5]. Despite its proven efficacy, CGA has not yet been integrated into routine care of older cancer patients in Germany, consistent with trends in most parts of the world.

1.2 Evidence for CGA in oncology

Recently, several randomized trials conducted in the USA (GAP70+[6], GAIN[7]), Denmark (GERICO)[8], Brazil (GAIN-S)[9], and Australia (INTEGERATE)[10] have demonstrated a significant benefit of implementing a CGA into the clinical care of older cancer patients receiving systemic cancer therapy. A subsequent systematic review on the effects of CGA for this population reported a reduction in treatment-related toxicities of Common Terminology Criteria of Adverse Events (CTCAE) grade 3-5, an improvement in quality of life (QoL), and an increased rate of treatment completion[5]. As a consequence, CGA is explicitly recommended as an integral part of geriatric cancer care by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO)[11], and the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO)[12].

Even though CGA-based prehabilitation plays a role in older adults undergoing major surgery[13], the evidence for CGA before cancer surgery remains less robust than that for systemic cancer therapies[14]. Nonetheless, CGA in the perioperative period was shown to significantly reduce ICU admissions, emergency room visits, and hospital readmissions among frail older patients undergoing gastrectomy for gastric cancer[15]. In addition, a large single-center analysis found a substantially lower 90-day postoperative mortality among older patients with cancer receiving geriatric co-management[16]. Given its evidence in other surgical areas[17], larger trials are needed to determine the impact of targeted geriatric interventions, particularly prehabilitation before major cancer surgery in older adults.

In older adults undergoing radiotherapy for cancer, pre-existing functional impairments are associated with worse QoL and physical function[18]. Despite that, radiotherapy does not necessarily exacerbate functional decline[18]. However, treatment protocols for radiotherapy are heterogenous and their tolerability may depend on factors such as dose intensity, the extent of radiation field, and concomitant chemotherapy[19]. Data on CGA in radiotherapy are very scarce[19] and results from randomized trials in frail patients are awaited.

1.3 Implementation of CGA into the routine cancer care of older adults in Germany: Description of the current situation

The German evidence-based guideline on CGA recommends a CGA for all cancer patients ≥ 70 years prior to systemic cancer therapy, and for those aged ≥ 65 years after a positive geriatric screening (e.g., G8 score ≤ 14 points)[20], to reduce treatment-induced toxicities CTCAE grade 3-5. Comparable recommendations exist in cancer-specific guidelines such as the German breast cancer guideline[21]. Despite the strong evidence and recommendations, CGA is not routinely implemented into cancer care of older adults in Germany because of different reasons. Firstly, geriatric outpatient departments are scare, and those that do exist typically have a specific focus, such as fall prevention and/or memory clinics. Secondly, many hospitals specializing in cancer care lack a geriatric department and/or a geriatric consultation service. Thus, there are currently several structural barriers impeding stringent implementation of CGA into routine cancer care in Germany besides a few local initiatives. Such an approach was integrated and evaluated through a propensity-score matching analysis at ‘Evangelische Kliniken Essen-Mitte’, a large community hospital in North Rhine-Westphalia/Germany. Patients receiving a CGA exhibited significantly higher chemotherapy completion and lower treatment-related mortality[22].

Another local initiative is the randomized “GOBI-Trial” (Geriatrisch-onkologische Behandlung und Intervention, Geriatric-Oncological Treatment and Intervention; DRKS00024974) at the University Hospital Würzburg/Comprehensive Cancer Center Mainfranken in Germany. This trial evaluates the impact of CGA versus standard-of-care on QoL and functional independence in older adults with cancer undergoing systemic therapy or radiation[23]. Although the results are still pending, the trial does not include the structured integration of CGA findings into multidisciplinary team meetings (MDTs) to support fitness-based treatment recommendations.

1.4 Study rationale

Based on the above-mentioned trials showing the efficacy of CGA in guiding treatment for older patients with cancer in western countries, the German guideline on CGA recommends its integration into routine oncological practice. However, as this contrasts with current care practice in German, its feasibility and efficacy within the German health care system remains elusive. As the superiority of CGA for cancer patients has already been demonstrated but its implementation remains very low, we designed the ‘Integration of Geriatric assessment-guided care plan modifications and interventions into clinical paths of older adults with cancer (GORILLA)’ trial. GORILLA is a bicentric trial which assesses the feasibility of CGA implementation into routine care, the patients’ willingness to participate, and the integration of CGA results into MDT. Its results will provide a framework to design a subsequent larger trial to assess the efficacy and cost effectiveness of CGA implementation within the German health care system.

2. Methods

2.1 Conceptual model, study design, aims, setting, and recruitment

2.1.1 Conceptual model and overview on trial procedures

This prospective, bicentric cohort study is designed to evaluate the feasibility of integrating CGA into routine care for older adults with cancer. During therapeutic evaluation for a newly diagnosed or progressive cancer, patients eligible for a CGA according to the German guideline on CGA (patients ≥ 65 years with a G8 score[24] of ≤ 14 points and/or patients ≥ 70 years regardless of their G8 Score) are approached and offered a CGA within a geriatric consultation during inpatient stay or outpatient appointment. Pre-screening with the oncogeriatric screening instrument G8 is applied to patients < 70 years because many individuals at that age are still very fit and may not benefit from a CGA, at the expense of resources. As G8 score < 15 points is related to frailty and increased geriatric deficits and was included as entry criterion in several randomized CGA trials[8]. Accordingly, the German CGA guideline recommends such a score as indication to perform a CGA in patients < 70 years. The geriatric assessment itself is performed by a trained nurse or medical doctoral candidate and the results, along with potential implications, are discussed with a geriatrician. A written summary of the CGA findings, including specific recommendations for geriatric interventions, is presented to the surgical and oncological care providers to inform treatment recommendations. The geriatrician also evaluates eligibility criteria and obtains informed study consent. CGA is performed as routine procedure, independent of potential trial enrollment, as recommended in the guideline. CGA and cancer-related data are systematically recorded, including a telephone follow-up after three months (± two weeks). During this call, the functional status (ADL), SARC-F, and QoL will be assessed. In addition, patients are asked whether they have received indeed the interventions recommended during the initial CGA. Individuals who refuse trial participation receive standard care without telephone follow-up, or further evaluation of CGA results. (Non)-consent is documented for primary endpoint assessment (see below).

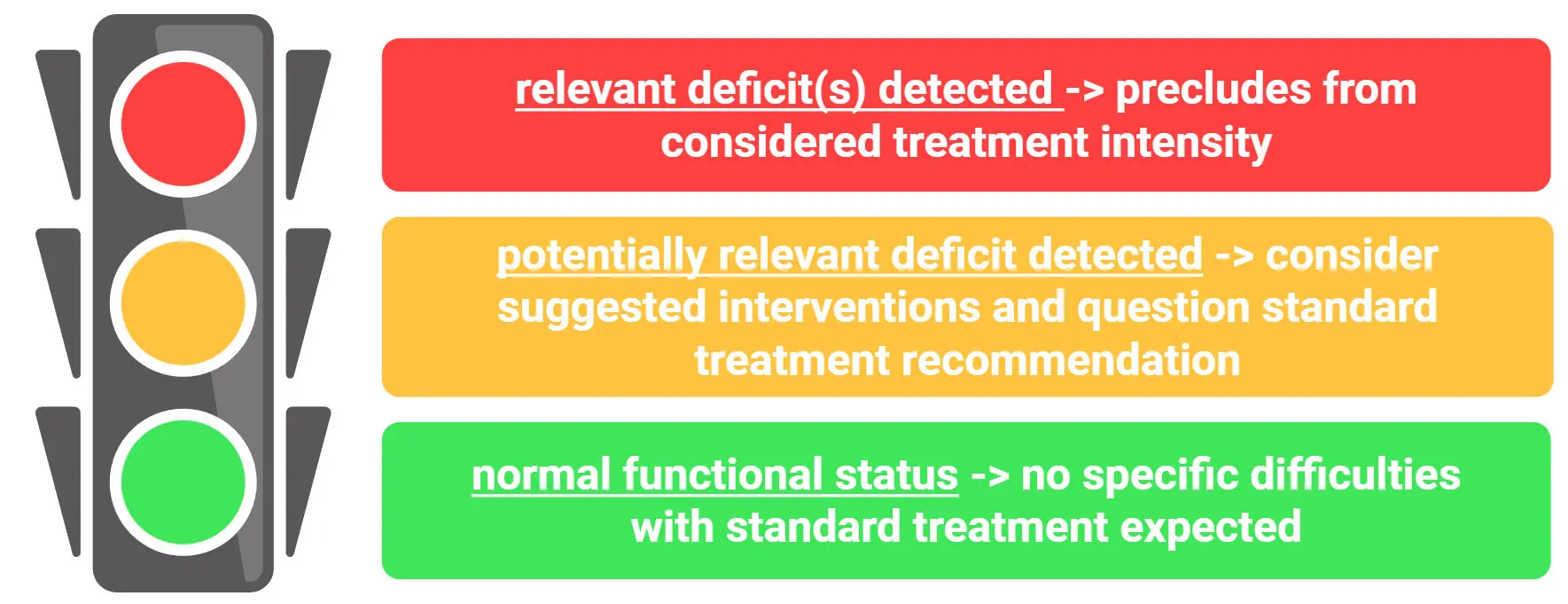

The results of the CGA are presented during the MDT discussion by a member of the geriatric team, to comment on CGA results and their potential implications. The overall results are summarized in the form of a traffic light system to facilitate rapid understanding of the patients’ capacity within a tight schedule (Figure 1). The traffic light translates into the following: green/‘normal functional status/no specific difficulties with standard treatment expected’, yellow/‘potentially relevant deficit detected, consider the suggested intervention and question standard treatment recommendation’, and red/‘relevant deficit detected that precludes from considered treatment intensity’ (Figure 1). Of note, traffic light grading does not merely reflect deficit sum scores but integrates treatment-specific risks for subsequent deterioration based on the identified deficits and anticipated treatment-related toxicities. Therefore, the same severity of a deficit may lead to different traffic light grading depending on the oncologic entity and the associated treatment burden. For instance, severe malnutrition may not prevent a patient from undergoing minor breast surgery but could be considered as a contraindication for major abdominal surgery. Similarly, moderate to severe polyneuropathy may not complicate treatment with checkpoint inhibitors but could preclude treatment modalities with a high risk for treatment-related polyneuropathy. In summary, the traffic light system provides a holistic approach based on individual vulnerability and treatment toxicity.

Figure 1. The traffic light for facilitated depiction of patient’s condition during multidisciplinary team meetings. Created in BioRender.com.

After the MDT, the patients’ primary care providers receive a brief questionnaire assessing whether their treatment recommendation has changed based on the CGA results and whether they regarded the geriatric presence as supportive (Supplementary 1). For patients who decline study participation but still receive the CGA as part of their routine care, these items are collected anonymously.

Upon trial completion, selected primary care providers are invited to participate in qualitative interviews to share their personal experiences and insights on CGA integration into MDT (Supplementary 2).

The detailed study procedures are depicted in Figure 2.

2.1.2 Aims, endpoints, and their rationale

The primary aim of this study is to assess the willingness of participation in the present CGA trial in a frail study population that is challenging to recruit into clinical trials. Secondary aims include the assessment of feasibility and quality measures for implementation of CGA and recruitment within 12 months, the acceptance of CGA reporting in MDT by primary oncological care providers, digital competence of patients, and patients’ priorities.

In detail, the following endpoints are assessed:

1) The primary endpoint is to estimate the willingness of participation with an accuracy of ± 7.5%.

This endpoint allows a realistic view on potential participation for a subsequent larger health services research study, and allows to design a confirmative follow-up trial, to estimate the sample size, and to avoid selection bias in this difficult-to-recruit population. This is of importance as frail patients are difficult to recruit and even trials specifically targeting older adults were shown to carry a bias relative to real-world cohorts[25].

The secondary endpoints are as follows:

2) Evaluation of feasibility and quality measures.

a. Completion rate of CGA prior to MDT.

b. Expenditure of time for CGA completion.

c. Presence rate of a geriatrician during MDT.

d. Qualitative measures for non-performance of CGA (absence of geriatricians, etc.).

These measures allow a comprehensive overview on the feasibility of CGA implementation and geriatric staff expenditure.

3) Descriptive evaluation of qualitative measures of CGA components, and QoL, subsequent recommended geriatric interventions and their initiation after 3 months follow-up.

As no standard-of-care is defined, geriatric interventions should be recommended based on defined deficits. The summary of recommended interventions, guided by clinical judgement, serves as a basis for further expert evaluation. Upon study completion, the generated list of interventions will be further processed by an expert Delphi process to develop protocols for standard operating procedures. In addition, the follow-up assessment of intervention initiation also enables identification of implementation barriers (e.g., long waiting lists for physiotherapy etc.).

4) Descriptive evaluation of polypharmacy and potential inappropriate medications (PIM).

Polypharmacy will be evaluated according to PIM, potential drug-drug-interactions, Beers[26] and Start/Stop criteria[27], and falls-risk-increasing-drugs (FRIDs)[28].

5) Evaluation of media competency and factors that are associated with media use.

Several digital health applications are approved for cancer patients in Germany, offering a tremendous window of opportunities to improve care. Thus, the prescription of these applications can be used as interventions, e.g., for cognitive training. Nonetheless, limited media competence among frail patients may hinder the effectiveness of such interventions. Therefore, a detailed analysis of media competence and potentially associated factors, such as cognitive impairment, will provide a realistic overview of whether digital health applications can be integrated into the care of older and frail cancer patients (Supplementary 3).

6) Evaluation of the impact of CGA integration into MDT on primary surgical/oncological care providers and their satisfaction.

This will be assessed through a questionnaire completed by primary oncological care providers after each patient discussion (Supplementary 1). The questionnaire includes both subjective evaluations (helpful/not helpful) and whether the original treatment plan was modified based on CGA findings (e.g., changes in chemotherapy dose or surgical treatment). This endpoint focuses on the physicians’ perspectives, independent of patient participation in the study. Additionally, at least one physician from each discipline (gynecology, oncology, urology, surgery) will be invited to participate in a qualitative interview at the conclusion of the study to evaluate the overall satisfaction with the integrated care path (Supplementary 2).

Exploratory endpoints are as follows:

7) Evaluation of patient priorities and their association with estimated cancer-independent life expectancy, functional status, and cancer prognosis.

Patient priorities regarding their cancer treatment are questioned and summarized (Supplementary 4). In this exploratory analysis, potential associations between the priorities and functional status, cancer-independent life expectancy, and cancer prognosis are evaluated.

8) Validation of the German Elderly Functional Index (ELFI) version.

The ELFI 2.0[29] is constructed from different items of the EORTC-ELD-14 and -C30 QoL questionnaires. ELFI is broadly used in English-speaking countries and was employed to assess the primary endpoint in the Australian INTEGERATE trial[10]. Recently, a Danish version has been validated[30]. However, no validated German version currently exists. Such a version will enable a better inter-trial comparison in future trials and is therefore included as additional endpoint.

9) Functional trajectories after three months via telephone follow-up.

Although the study population is highly heterogenous regarding treatment modalities and baseline characteristics, a descriptive analysis of functional trajectories from baseline status to three-month follow-up is provided to get an overview on potential courses, and to allow an appropriate comparison of QoL and functional outcome after three months.

2.1.3 Trial setting

The study will include approximately 60 to 100 patients, with the exact number depending on the overall willingness of patients to participate. In addition, the study will involve the primary healthcare providers of the enrolled patients, including oncologists, surgeons, gynecologists, and other relevant specialists, who are members of the respective MDTs and will be invited to participate in selected study procedures and complete relevant questionnaires. The study will be conducted at the two participating centers:

1) Marien Hospital Herne and their respective departments involved in oncological care (Urology, Gynecology, Oncology, Geriatrics, and Surgery).

2) University Hospital Ulm, Department of Gynecology, together with the Agaplesion Bethesda Ulm and the Institute for Geriatric Research, Ulm University.

2.1.4 Recruitment, eligibility and consensus

Eligibility criteria are broad to minimize selection bias. Patients have either a newly diagnosed cancer or progressive/relapsed disease requiring a new line of treatment, including radiotherapy, surgery, or a systemic treatment (e.g., chemotherapy, targeted therapy, immunotherapy, cellular therapy, or endocrine therapy, including combined treatment approaches), and must be considered for MDT discussion. The detailed in- and exclusion criteria are listed in Table 1. Several cancer entities are excluded either as they generally do not require a comprehensive treatment approach or do not substantially impact life expectancy (e.g., basal cell carcinoma), or as the short-term outcomes are dismal (e.g., glioblastoma, acute leukemia). Written informed consent is obtained from all participants. The number of patients rejecting participation is recorded. Written consent from participating physicians in MDTs is obtained prior to the first MDT.

| Inclusion Criteria |

| Patients ≥ 65 years with a G8 score ≤ 14 points |

| Patients ≥ 70 years, independent of G8 score |

| First manifestation of cancer or progressive disease |

| Evaluation of (new) line of therapy including primary radiotherapy or upfront surgery, adjuvant therapy, curative or palliative chemo-, immune- or targeted therapy planned; treatment decision is not finalized/presentation of patient in MDT is planned |

| All cancer types except those listed in the exclusion criteria |

| Patient’s capacity to consent as determined by judgement of treating physician |

| Exclusion Criteria |

| Unresectable cholangiocarcinoma, glioblastoma, acute leukemias, basalioma, melanoma without intended systemic treatment |

| Unable to understand the informed consent due to clinically overt dementia and/or language barriers |

2.2 Measures

Patient-related measures will be collected during the initial geriatric consultation (CGA) and during the three-month follow-up. Care provider measures are requested during the MDT meeting and during selected structured interviews after completion of study recruitment. Study instruments are listed in Table 2. Additional questionnaires are included in the Supplementary materials. The German versions are available upon request.

| Domain | Assessment method |

| Patient-related measures | |

| Functional status and Mobility | Activities of Daily Living (Barthel)[31] Instrumental Activities of Daily Living[32] Assessment of falls within last 12 months (as part of SARC-F questionnaire)[33] Short physical performance battery[34] |

| Comorbidity | Charlson Comorbidity Index[35] Need for hearing aid and/or visual impairment (yes/no; Supplementary 5) |

| Social functioning and support | 8 questions adapted from ASCO guideline[11] (Supplementary 6) |

| Psychological health | DIA-S[36] Psychological Distress Thermometer[37] |

| Frailty | Clinical Frailty Scale[38] |

| Nutrition | Mini Nutritional Assessment Short Form[39] |

| Cognition | MoCA Test (study center 1)[40] 5-min MoCA or MMSE (study center 2)[41] |

| Sarcopenia | SARC-F[33,42] hand grip strength |

| Polypharmacy | assessment of current medication, potentially inappropriate medication, drug-drug-interactions |

| Dysphagia Screening | DSTG[43] |

| Patient priorities | What matters most to you regarding your cancer treatment (Supplementary 4)? |

| Risk assessment for delirium (only in patients considered for surgery) | SurgeAhead Risk prediction tool[44] |

| Quality of life | ELFI 2.0 [11] EORTC QLQ-C30[45] (only physical, role and social functioning)/ QLQ-ELD14[46] (mobility; only at initial visit; time for assessment is not included in CGA time)EQ-5D-5L[47] (only study center 1; time for assessment is not included in CGA time) |

| Media competency | Basic questions on use of smart phones/tablets/computer and reasons for use as an advanced and modern IADL (Supplementary 3) |

| Oncological care provider-related measures | |

| Evaluation of CGA implementation into MDT on single case basis | Questionnaire (Supplementary 1) |

| Qualitative evaluation of CGA implementation into MDT | Structured interview (Supplementary 2) |

CGA: comprehensive geriatric assessment; DIA-S: Depression im Alter – Skala; ELFI: Elderly Functional Index; EQ-5D-5L: European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions 5 levels; EORTC QLQ-C30: European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30; EORTC QLQ-ELD14: European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire – Elderly-14 items; IADL: instrumental activities of daily living; MDT: multidisciplinary team; ASCO: American Society of Clinical Oncology; MOCA: Montreal Cognitive Assessment; MMSE: Mini Mental State Examination; DSTG: Dysphagia Screening Tool Geriatrics.

2.2.1 Patient-related measures

Patient-related clinical measures include tumor characteristics and treatment details, CGA results, and the follow-up data. For patients who decline study participation, only their refusal will be documented. As no standardization of assessed CGA domains is available, instruments were selected to assess respective domains based on the established routine methods of the participating centers and their relevance for guiding interventions. In addition, a CGA is supposed to include at least five different dimensions and to take at least 15 minutes, according to the German Guideline on CGA[20]. The rationale for selected GA domains is as follows:

1) Mobility: The Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) was selected over the commonly used ‘timed-up-and-go’ test in Germany, as the SPPB dissects mobility aspects into balance, gait speed, and lower extremity strengths[34]. SPPB offers a better comprehension of mobility and gait disturbances, particularly in the presence of treatment-related toxicities such as polyneuropathy affecting balance or steroid myopathy leading to proximal lower extremity weakness.

2) Cognition: As both study centers employ different cognitive assessment tools and the health personnel are trained differently, we decided to follow the respective routine path for cognitive assessment. Specifically, study center 1 uses the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA[40]), whereas study center 2 employs the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE[41]). This pragmatic approach can be considered reasonable, as total scores from the MMSE and MoCA (including the 5-minute MoCA) can be compared using an established conversion table for comparability[48].

2.2.2 Care provider – related measures

Primary care providers are assessed regarding the integration of CGA into the MDT and its impact on their treatment recommendations after the respective MDTs. For each patient case, one questionnaire is requested by each healthcare provider who was present during the MDT. Additionally, structured interviews will be performed with at least one provider from each specialty after study recruitment is completed. The questionnaires and interview guides are depicted in Supplementary 1 and Supplementary 2.

2.3 Data collection and statistical analysis

2.3.1 Sample size estimation and primary endpoint

The sample size estimation is based on the primary endpoint and the feasibility to recruit the expected 60-100 patients at two centers within 6-12 months. The primary endpoint, defined as the estimation of willingness to participate with an accuracy of ± 7.5%, is dependent on the real participation rate (p) and the number of approached patients (N). Narrow confidence intervals (CIs) correspond to higher estimation precision, and the width of the CI broadens with increased number of approached patients. For a real participation rate (p) of ~50% (p = 0.5), this estimation is the lowest and 200 patients would be required to achieve an accuracy of estimation of ±7.5%. The willingness to participate will be estimated using the Clopper-Pearson interval for the parameter p of the binominal distribution. For that, the limits of the confidence interval (95% CI(p)) represent the largest and the smallest, respectively, value of p that allows the assumption to achieve the estimated number of participants. The lower the real participation rate, the greater the likelihood that selection bias will affect the cohort. Such a bias could eventually impede the design of a future trial aiming at tailored geriatric interventions in a real-world patient cohort. As an example: If the real participation rate is ≥ 80% (as expected), 60-100 patients would be in the range to estimate with the aimed accuracy. The table in Supplementary 7 summarizes the size of CIs in dependency of p and N.

The first interim analysis will be performed after recruitment of 50 patients to evaluate a preliminary result of the primary endpoint and to guide further recruitment strategies. If the recruitment takes more than 12 months to achieve the primary endpoint, the trial will be prematurely closed, and the primary endpoint will be considered unmet. In this case, the secondary endpoints are assessed, if possible.

This endpoint provides a realistic view on potential participation in a larger health services research study to mitigate selection bias in this difficult-to-recruit population. Importantly, patients who refuse to participate will still receive integrated onco-geriatric care as standard-of-care. However, only the primary surgical/oncological care providers will be assessed regarding whether the presentation of CGA results during MDT guided their treatment recommendation.

2.3.2 Secondary endpoints and their statistical analysis

1) Evaluation of feasibility and quality measures.

a. Completion rate of CGA prior to scheduled MDT: This endpoint is purely descriptive as part of the quality assessment and will be presented as percentages.

b. Expenditure of time for CGA completion: The time for CGA completion will be presented as median with its ranges (minimum, maximum).

c. Presence rate of a geriatrician during MDT: This quality measure is also descriptive and will be presented as percentages.

d. Qualitative measures for non-performance of CGA: Reasons are descriptively summarized, including the absence of geriatricians at the requested CGA, premature patient discharge, or other factors.

2) Descriptive evaluation of patient characteristics, qualitative measures of CGA components, and QoL, subsequent recommended geriatric interventions and their initiation after the three-month follow-up.

Descriptive data on patient characteristics, GA results, tumor characteristics, curative/palliative intent of the treatment approach, and initiated treatment modalities, are systematically collected and thoroughly described. This approach includes summarizing data using means, medians, range values, and standard deviations for continuous variables, as well as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. This will provide a comprehensive overview of the study cohort and serves as the prerequisites to calculate samples sizes in subsequent larger trials.

The suggested interventions based on deficits and proposed treatment will be discussed in regular online meetings with the participating physicians to minimize inter-rater variability. At the conclusion of this trial, a list of interventions will be generated and forwarded to a Delphi process with other geriatricians working in oncology across Germany to adapt the recommendations to the German health care system. This list will not contain any patient-related data, ensuring compliance with data protection regulations. Furthermore, barriers to the implementation of recommended interventions are summarized.

3) Descriptive evaluation of polypharmacy and PIM.

Polypharmacy will be evaluated according to PIM, potential drug-drug-interactions, Beers criteria, and FRIDs. Potential drug-drug-interactions are classified as moderate or severe. Both the total number of interactions per patient and that of moderate/severe interactions are quantified. PIM are analyzed according to Beers criteria[26] and Start/Stop criteria[27], and FRIDs are also assessed[28]. If more than 10 cases with the same cancer treatment approach are included, the numbers of potential drug-drug interactions, PIM, and FRIDs per patient are compared across the treatment modalities.

4) Evaluation of media competency and factors that are associated with their use.

Media use will be analyzed descriptively (percentages; quantification of detailed use). To assess the media competency in relation to GA results, the overall media use will be rated, and binomial logistic regression analysis will be performed to explore potential associations with impaired GA domains and patient characteristics including their educational level.

5) Qualitative evaluation of the integration of CGA into the tumor board.

For this endpoint, the satisfaction of non-geriatric disciplines with the information gained through the CGA presentation during the MDT will be assessed. To investigate this endpoint, participants are given a questionnaire after each patient of interest was discussed during the MDT. This encompasses both subjective evaluation, helpful/not helpful, and whether the original treatment plan was changed based on the objective estimate from CGA, e.g., change in planned chemotherapy dose intensity, or the extend of surgical treatment. This endpoint is independent of patient participation in the study, as it primarily assesses the involved physicians. All cancer care providers willing to participate will be assessed throughout the trial, without limitation on sample size. The respondents of this questionnaire (the primary cancer care providers) are further asked for their age and extent of clinical experience. The subjective evaluation is analyzed descriptively. Furthermore, respondents’ estimation of the usefulness of integrating CGA results into the MDT is correlated with their age and years of clinical experience. The respective questionnaire is attached in the Supplementary 1. In addition, once study recruitment is complete, at least one primary healthcare provider from each discipline (urology, surgery, gynecology, oncology, radiotherapy) will be approached for a qualitative interview (Supplementary 2 for interview questions), to receive a more detailed picture on geriatric-oncological interactions and the presentation of CGA during the MDTs.

6) Evaluation of patient priorities and their association with estimated cancer-independent life expectancy, functional status, and cancer prognosis.

Patient priorities regarding their cancer treatment are assessed using three questions on a five-point Likert scale (Supplementary 4). These priorities are descriptively summarized (median; percentages). Their potential associations with functional status, cancer-independent life expectancy, and cancer prognosis are evaluated in multivariate analysis.

7) Validation of the German ELFI version.

To validate the German ELFI version, the ELFI score[29] will be assessed twice during our trial: at the initial CGA and at the follow-up after three months. ELFI validation will be assessed as reported by Jespersen et al.[30]. In brief, ELFI scores will be tested for consistency within the single domains and correlated with G8 score, SPPB results, and functional decline, as measured by ADL/IADL loss over the three-month period.

8) Functional trajectories after three month follow up.

To get an overview on functional trajectories during short-term follow-up, QoL, SARC-F, and ADL are compared descriptively between baseline and follow-up (percentages of each group with equal status, functional improvement, or decline). Results are summarized using a Sankey diagram[49] to illustrate the proportion of patients in each functional group at the two time points.

2.4 Funding and ethical approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Ulm on October 30, 2024 (351/24—FSt/Sta), and by the Ethics Committee of Westphalia-Lippe on January 23, 2025 (2024-700-f-S).

No external funding is provided. The study is registered at German Clinical Trials Register (Deutsches Register für klinische Studien, DRKS), DRKS00035569.

3. Discussion

Although a growing body of evidence suggests a major impact of CGA on reduction of treatment-related toxicities, preservation of QoL, and improvement of treatment completion rates[14], this procedure lacks implementation within the German health care system. This situation is not unique to Germany; despite several international recommendations for CGA in oncology, including the ASCO guidelines[50,51] and the ESMO[12] recommendation, few centers around the world routinely perform a CGA. Given this limitation, implementation with thorough quality assessment is supposed to be a key priority. A crucial component of such implementation is the development of detailed pathways, including the production of ‘standard-operating procedure’ protocols. This process is a time-consuming and crucial step which requires continuous involvement from all participating disciplines. Trials on CGA have focused mostly on systemic cancer treatment. The strength of our study lies in the dual approach: the assessment of patients undergoing different treatment modalities (systemic therapies, radiation, surgery, or a combination), and the assessment of primary care providers’ attitudes toward incorporating CGA into MDT discussions. In addition, geriatric interventions to compensate specific geriatric deficits, especially in the context of defined cancer treatments, are individualized and patient-centered. Although many interventions may overlap, considerable interindividual heterogeneity can be expected, making the impact of any single intervention elusive. Therefore, we will summarize all intervention recommendations thoroughly and forward those to a Delphi process to achieve expert-level standardization. Additionally, the practical feasibility of interventions can depend on local availabilities (e.g., waiting lists for physiotherapy), or national reimbursement policies. Moreover, the respective maximum achievable benefit may require certain patient capacities. For instance, a digital health application (“NeuroNation”[52]) for neurocognitive training is approved in Germany and reimbursed by healthcare insurances, but its use requires patients to possess basic digital competencies. Although this application will be considered as a potential intervention within our trial, existing data are insufficient to determine what proportion of frail older adults with cognitive impairment possess suitable digital devices and can use those independently. Therefore, this data will be acquired.

4. Limitations

Despite its comprehensive approach, this study has several limitations. Due to strong evidence that CGA can reduce treatment-related toxicities, we had ethical concerns about including a randomization between CGA and standard-of-care; therefore CGA was offered to all patients. As a result, the study lacks a comparator arm and cannot directly evaluate the efficacy of CGA integration. A matched-pair-analysis, an alternative, could address this gap. Nonetheless, CGA provides a comprehensive, functional view on patients with potential prognostic implications that is not available in routine electronical medical records. For instance, patients with cognitive impairments were shown to experience only one-third the survival duration of non-impaired patients, even when receiving similar treatment in a specialized geriatric oncology program[53]. Those aspects would be missed in a matched-pair-analysis without GA data and we decided thus against such an analysis.

In addition, the inclusion of patients with a broad range of cancer entities could further impede the matching process. This indicates how even a well-performed matched-pair analysis may have significant limitations, making it neither effective nor appropriate for this trial analysis.

Another potential limitation includes that assessment of primary care providers is not blinded, as it occurs immediately after corresponding patient discussion. This may lead to a bias.

Concerning the cost of CGA implementation, previous studies have reported CGA to be cost-saving[54], cost-neutral[55] or with a low marginal cost[56]. Besides the general lack of CGA efficacy data in the German healthcare system, no data for cost effectiveness is available. Such data are essential for informing policy decisions and for implementing CGA into routine care paths. Although our trial will not provide this information, based on its impact on treatment recommendations, a cost effectiveness analysis of a subsequent trial can be planned. Notably, as a subsequent trial will face the same ethical concerns for a comparator arm without geriatric interventions, a stepped-wedge design allowing sufficient comparison may be the most appropriate option.

5. Conclusions

The present study ought to provide valuable insights into the feasibility of CGA implementation into daily clinical practice of older cancer patients by integrating CGA results in case-specific discussion during MDT. We expect a high participation rate due to the broad inclusion criteria, as well as clearly defined requirements regarding time expenses and required personnel. These results shall form the basis to design a larger trial focusing on efficacy and cost-effectiveness, while also yielding quality measures of CGA integration into routine care.

Supplementary materials

The supplementary material for this article is available at: Supplementary materials.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the patients for participation. BioRender.com was used to create the figures. The study concept was in part presented at the 2025 DGG Congress “Geriatrie - Gefragt, Gereift, Gestärkt”, held from September 18-20 in Weimar, Germany, as well as at the 2025 EuGMS annual congress “New landscapes in geriatric medicine”, held from September 24-26 in Reykjavik, and the SIOG 2025 annual conference “Bridging Research and Clinical Practice in Geriatric Oncology”, held from November 20-22 in Ghent, Belgium.

Authors contributions

Mayland RS, Neuendorff NR, Verri FM, Deterding M, Heublein S, Turki AT, Roghmann F, Wirth R, Denkinger M: Conceptualization, writing-review & editing.

Aslan A, Strumberg D: Writing-review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

Neuendorff NR has received honoraria and travel support from Janssen-Cilag, Medac, Novartis, Pfizer, AbbVie, and Jazz Pharmaceuticals. Neuendorff NR is an Editorial Board Member of Ageing and Cancer Research & Treatment. Wirth R has received honoraria from Novartis, Danone, and InfectoPharm. Turki AT has received research funding from Neovii Biotech; consultancy fees from CSL Behring, Maat Pharma, Biomarin, Pfizer, and Onkowissen; and travel reimbursements from Neovii and Novartis. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Ulm on October 30, 2024 (351/24 – FSt/Sta), and by the Ethics Committee of Westphalia-Lippe on January 23, 2025 (2024-700-f-S).

Consent to participate

All patients included in this study gave written informed consent before inclusion.

Consent for publication

Not yet applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The data and materials could be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.

Funding

None.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

References

-

1. Zentrum für Krebsregisterdaten im Robert Koch-Institut. Datenbankabfrage mit Schätzung der Inzidenz, Prävalenz und des Überlebens von Krebs in Deutschland auf Basis der epidemiologischen Landeskrebsregisterdaten. Mortalitätsdaten bereitgestellt vom Statistischen Bundesamt [Internet]. Berlin: Robert Koch-Institut; 2024 Sep 5 [cited 2025 Aug 4]. Available from: https://www.krebsdaten.de/Krebs/DE/Datenbankabfrage/datenbankabfrage_stufe1_node.html

-

2. Neuendorff NR, Reinhardt HC, Christofyllakis K. Is less always more? Emerging treatment concepts in geriatric hemato-oncology. Ageing Cancer Res Treat. 2024;1:59.[DOI]

-

3. Wedding U. Geriatrisches assessment vor onkologischer therapie. Urologe. 2013;52(6):827-831.[DOI]

-

4. Extermann M, Hurria A. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(14):1824-1831.[DOI]

-

5. Disalvo D, Moth E, Soo WK, Garcia MV, Blinman P, Steer C, et al. The effect of comprehensive geriatric assessment on care received, treatment completion, toxicity, cancer-related and geriatric assessment outcomes, and quality of life for older adults receiving systemic anti-cancer treatment: A systematic review. J Geriatr Oncol. 2023;14(8):101585.[DOI]

-

6. Mohile SG, Mohamed MR, Xu H, Culakova E, Loh KP, Magnuson A, et al. Evaluation of geriatric assessment and management on the toxic effects of cancer treatment (GAP70+): A cluster-randomised study. Lancet. 2021;398(10314):1894-1904.[DOI]

-

7. Li D, Sun CL, Kim H, Soto-Perez-de-Celis E, Chung V, Koczywas M, Fakih M, Chao J, Chien LC, Charles K, Hughes SF. Geriatric assessment–driven intervention (GAIN) on chemotherapy-related toxic effects in older adults with cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(11):e214158.[DOI]

-

8. Lund CM, Vistisen KK, Olsen AP, Bardal P, Schultz M, Dolin TG, et al. The effect of geriatric intervention in frail older patients receiving chemotherapy for colorectal cancer: A randomised trial (GERICO). Br J Cancer. 2021;124(12):1949-1958.[DOI]

-

9. Bergerot CD, Bergerot PG, Razavi M, da Silva França MV, da Silva JR, Cerveira JA, et al. Telehealth geriatric assessment and supportive care intervention (GAIN-S) program: A randomized clinical trial. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2025;23(6):219-226.[DOI]

-

10. Soo WK, King MT, Pope A, Parente P, Dārziņš P, Davis ID. ntegrated Geriatric Assessment and Treatment Effectiveness (INTEGERATE) in older people with cancer starting systemic anticancer treatment in Australia: a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2022;3(9):e617-e627.[DOI]

-

11. Dale W, Klepin HD, Williams GR, Alibhai SMH, Bergerot C, Brintzenhofeszoc K, et al. Practical assessment and management of vulnerabilities in older patients receiving systemic cancer therapy: Asco guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(26):4293-4312.[DOI]

-

12. Loh KP, Liposits G, Arora SP, Neuendorff NR, Gomes F, Krok-Schoen JL, et al. Adequate assessment yields appropriate care—the role of geriatric assessment and management in older adults with cancer: A position paper from the ESMO/SIOG Cancer in the Elderly Working Group. ESMO Open. 2024;9(8):103657.[DOI]

-

13. Skořepa P, Ford KL, Alsuwaylihi A, O'Connor D, Prado CM, Gomez D, et al. The impact of prehabilitation on outcomes in frail and high-risk patients undergoing major abdominal surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Nutr. 2024;43(3):629-648.[DOI]

-

14. Disalvo D, Garcia MV, Soo WK, Phillips J, Lane H, Treleaven E, et al. The effect of comprehensive geriatric assessment on treatment decisions, supportive care received, and postoperative outcomes in older adults with cancer undergoing surgery: A systematic review. J Geriatr Oncol. 2025;16(3)[DOI]

-

15. Chang CY, Lu CH, Hung CY, Liu KH, Hsu JT, Tsai CY, et al. Effect of geriatric interventions on postoperative outcomes in frail older patients undergoing elective gastrectomy for gastric cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2025;16(7):102324.[DOI]

-

16. Shahrokni A, Tin AL, Sarraf S, Alexander K, Sun S, Kim SJ, et al. Association of geriatric comanagement and 90-day postoperative mortality among patients aged 75 years and older with cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8):e209265.[DOI]

-

17. Snowdon D, Haines TP, Skinner EH. Preoperative intervention reduces postoperative pulmonary complications but not length of stay in cardiac surgical patients: A systematic review. J Physiother. 2014;60(2):66-77.[DOI]

-

18. Eriksen GF, Benth JŠ, Grønberg BH, Rostoft S, Kirkhus L, Kirkevold Ø, et al. Geriatric impairments are associated with reduced quality of life and physical function in older patients with cancer receiving radiotherapy - A prospective observational study. J Geriatr Oncol. 2023;14(1):101379.[DOI]

-

19. Amini A, Morris L, Ludmir EB, Movsas B, Jagsi R, VanderWalde NA. Radiation therapy in older adults with cancer: A critical modality in geriatric oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(16):1806-1811.[DOI]

-

20. AWMF Leitlinienregister [Internet]. Available from: https://register.awmf.org/de/leitlinien/detail/084-003

-

21. Leitlinienprogramm-Onkologie (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, AWMF). S3-Leitlinie Früherkennung, Diagnostik, Therapie und Nachsorge des Mammakarzinoms. Langversion 5.01 [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 18]. Available from: http://www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/leitlinien/mammakarzinom/

-

22. Stahl MK, Ertl SW, Engelmeyer P, Heuer HC, Christoph DC. Impact of geriatric assessment on the tolerability of combination chemotherapy in older patients with advanced cancer: A matched-pair analysis. Oncol Res Treat. 2023;46(3):100-105.[DOI]

-

23. Hüttmeyer M, Tatschner K, Jentschke E, Roch C, Deschler-Baier B. Increasing the evidence for comprehensive geriatric assessment – Outlook on another work in progress. J Geriatr Oncol. 2025;16(2)[DOI]

-

24. Bellera CA, Rainfray M, Mathoulin-Pélissier S, Mertens C, Delva F, Fonck M, et al. Screening older cancer patients: First evaluation of the G-8 geriatric screening tool. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(8):2166-2172.[DOI]

-

25. Habib MH, Alibhai SMH, Puts M. How representative are participants in geriatric oncology clinical trials? The case of the 5C RCT in geriatric oncology: A cross-sectional comparison to a geriatric oncology clinic. J Geriatr Oncol. 2024;15(2):101703.[DOI]

-

26. 2023 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2023 updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;71(7):2052-2081.[DOI]

-

27. O’Mahony D, Cherubini A, Guiteras AR, Denkinger M, Beuscart JB, Onder G, et al. Stopp/start criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: Version 3. Eur Geriatr Med. 2023;14(4):625-632.[DOI]

-

28. van der Velde N, Seppala LJ, Hartikainen S, Kamkar N, Mallet L, Masud T, et al. European position paper on polypharmacy and fall-risk-increasing drugs recommendations in the world guidelines for falls prevention and management: Implications and implementation. Eur Geriatr Med. 2023;14(4):649-658.[DOI]

-

29. Soo WK, King M, Pope A, Steer C, Devitt B, Chua S, et al. The elderly functional index (elfi), a patient-reported outcome measure of functional status in patients with cancer: A multicentre, prospective validation study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021;2(1):e24-e33.[DOI]

-

30. Jespersen E, Soo WK, Minet LR, Eshoj HR, King MT, Pfeiffer P, et al. External validation and diagnostic value of the elderly functional index version 2.0 for assessing functional status and frailty in older danish patients with gastrointestinal cancer receiving chemotherapy: A prospective, clinical study. J Geriatr Oncol. 2024;15(1):101675.[DOI]

-

31. Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: The Barthel index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61-65.[PubMed]

-

32. Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living1. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179-186.[DOI]

-

33. Malmstrom TK, Morley JE. SARC-F: A simple questionnaire to rapidly diagnose sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(8):531-532.[DOI]

-

34. Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, Glynn RJ, Berkman LF, Blazer DG, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: Association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol. 1994;49(2):M85-M94.[DOI]

-

35. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-383.[DOI]

-

36. Heidenblut S, Zank S. Entwicklung eines neuen depressionsscreenings für den einsatz in der geriatrie. Z Gerontol Geriat. 2010;43(3):170-176.[DOI]

-

37. Hurria A, Li D, Hansen K, Patil S, Gupta R, Nelson C, et al. Distress in older patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(26):4346-4351.[DOI]

-

38. Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, Bergman H, Hogan DB, McDowell I, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. Can Med Assoc J. 2005;173(5):489-495.[DOI]

-

39. Kaiser MJ, Bauer JM, Ramsch C, Uter W, Guigoz Y, Cederholm T, et al. Validation of the mini nutritional assessment short-form (mna®-sf): A practical tool for identification of nutritional status. J Nutr Health Aging. 2009;13(9):782-788.[DOI]

-

40. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, et al. The montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695-699.[DOI]

-

41. William Molloy D, Standish TIM. A guide to the standardized mini-mental state examination. Int Psychogeriatr. 1997;9:87-94.[DOI]

-

42. Drey M, Ferrari U, Schraml M, Kemmler W, Schoene D, Franke A, et al. German version of SARC-F: Translation, adaption, and validation. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(6):747-751.[DOI]

-

43. Thiem U, Jäger M, Stege H, Wirth R. Diagnostic accuracy of the ‘Dysphagia Screening Tool for Geriatric Patients’ (DSTG) compared to Flexible Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing (FEES) for assessing dysphagia in hospitalized geriatric patients – a diagnostic study. BMC Geriatr. 2023;23(1):856.[DOI]

-

44. Leinert C, Fotteler M, Kocar TD, Dallmeier D, Kestler HA, Wolf D, et al. Supporting SURgery with GEriatric Co-Management and AI (SURGE-Ahead): A study protocol for the development of a digital geriatrician. PLoS One. 2023;18(6):e0287230.[DOI]

-

45. Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, et al. The european organization for research and treatment of cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365-376.[DOI]

-

46. Wheelwright S, Darlington AS, Fitzsimmons D, Fayers P, Arraras JI, Bonnetain F, et al. International validation of the EORTC QLQ-ELD14 questionnaire for assessment of health-related quality of life elderly patients with cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;109(4):852-858.[DOI]

-

47. Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, Janssen MF, Kind P, Parkin D, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res. 2011;20(10):1727-1736.[DOI]

-

48. Fasnacht JS, Wueest AS, Berres M, Thomann AE, Krumm S, Gutbrod K, et al. Conversion between the montreal cognitive assessment and the mini-mental status examination. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;71(3):869-879.[DOI]

-

49. Otto E, Culakova E, Meng S, Zhang Z, Xu H, Mohile S, et al. Overview of sankey flow diagrams: Focusing on symptom trajectories in older adults with advanced cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2022;13(5):742-746.[DOI]

-

50. Williams GR, Hopkins JO, Klepin HD, Lowenstein LM, Mackenzie A, Mohile SG, et al. Practical assessment and management of vulnerabilities in older patients receiving systemic cancer therapy: ASCO guideline questions and answers. JCO Oncol Pract. 2023;19(9):718-723.[DOI]

-

51. Bergerot CD, Temin S, Verduzco-Aguirre HC, Aapro MS, Alibhai SMH, Aziz Z, et al. Geriatric assessment: ASCO global guideline. JCO Glob Oncol. 2025;(11):e2500276.[DOI]

-

52. Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte (BfArM). Fachkreise: Verzeichnis [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 2]. Available from: https://diga.bfarm.de/de/verzeichnis/01113/fachkreise

-

53. Robb C, Boulware D, Overcash J, Extermann M. Patterns of care and survival in cancer patients with cognitive impairment. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2010;74(3):218-224.[DOI]

-

54. Rich MW, Beckham V, Wittenberg C, Leven CL, Freedland KE, Carney RM. A multidisciplinary intervention to prevent the readmission of elderly patients with congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(18):1190-1195.[DOI]

-

55. Cohen HJ, Feussner JR, Weinberger M, Carnes M, Hamdy RC, Hsieh F, et al. A controlled trial of inpatient and outpatient geriatric evaluation and management. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(12):905-912.[DOI]

-

56. Keeler EB, Robalino DA, Frank JC, Hirsch SH, Maly RC, Reuben DB. Cost-effectiveness of outpatient geriatric assessment with an intervention to increase adherence. Med Care. 1999;37(12):1199-1206.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite