Yu-Xuan Lyu, School of Medicine, Institute of Homeostatic Medicine, and Institute of Advanced Biotechnology, Southern University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen 518055, Guangdong, China. E-mail: lvyx@sustech.edu.cn

Abstract

Immunosenescence is a biological process accompanying ageing, characterized by increased susceptibility to infections, reduced vaccine efficacy, and the development of chronic low-grade inflammation. Although immunosenescence is systemic, the relative contribution and compensability of each organ in the adaptive immune axis remain debated. We consolidate current evidence supporting a thymus-centric model of immune ageing. In this model, early and progressive thymic involution, marked by thymic epithelial cell attrition, FOXN1 decline, and architectural disruption, emerges as the principal constraint on de novo naive T‑cell production and T-cell receptor (TCR) repertoire renewal. In contrast, age‑related changes in bone marrow and spleen often exhibit partial compensability through peripheral redistribution and clinical interventions, sustaining counts but not restoring de novo diversity. We evaluate mechanisms of thymic involution, inter-organ communication, and cross-species parallels, identifying shared features across animal models. Quantitative readouts, including age-associated declines in sjTRECs and TCR-β repertoire diversity, further support the thymus-centricity. Clinically, constrained thymopoiesis may undercut vaccine responsiveness and reduce the efficacy of cancer immunotherapies (chimeric antigen receptor T-cell and immune checkpoint inhibitors) in older adults. We assess genetic, pharmacological, and bioengineering strategies to preserve or restore thymic function and outline translational paths and endpoints for future trials.

Keywords

1. Introduction

Global population ageing, accompanied by a loss of functional capacity, represents one of the major demographic challenges of the 21st century. As individuals age, disruptions of immune and metabolic homeostasis lead to and accelerate numerous age-associated diseases, increase susceptibility to infections, blunt vaccine efficacy, and promote chronic, low-grade inflammation (inflammageing)[1-3]. The biological foundation underlying these phenomena is immunosenescence, a systemic ageing process of the immune system that extends beyond normal physiological changes and significantly undermines the efficacy of modern immunotherapeutic approaches, such as chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy (CAR-T) and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI), particularly in the elderly. Clinically, age-related immunosenescence is reflected by a decline in complete response rates to CD19-directed CAR-T therapy from roughly 72% in the < 44 year old group to about 45% in those older than 60 years, and by smaller survival gains from ICI in very old patients compared with younger adults[4,5]. These patterns are consistent with data linking T-cell senescence and reduced T-cell fitness to impaired CAR-T performance[6]. A primary driver of this decline is the sustained reduction in T-cell repertoire diversity, coupled with impaired production of naive T-cells[7].

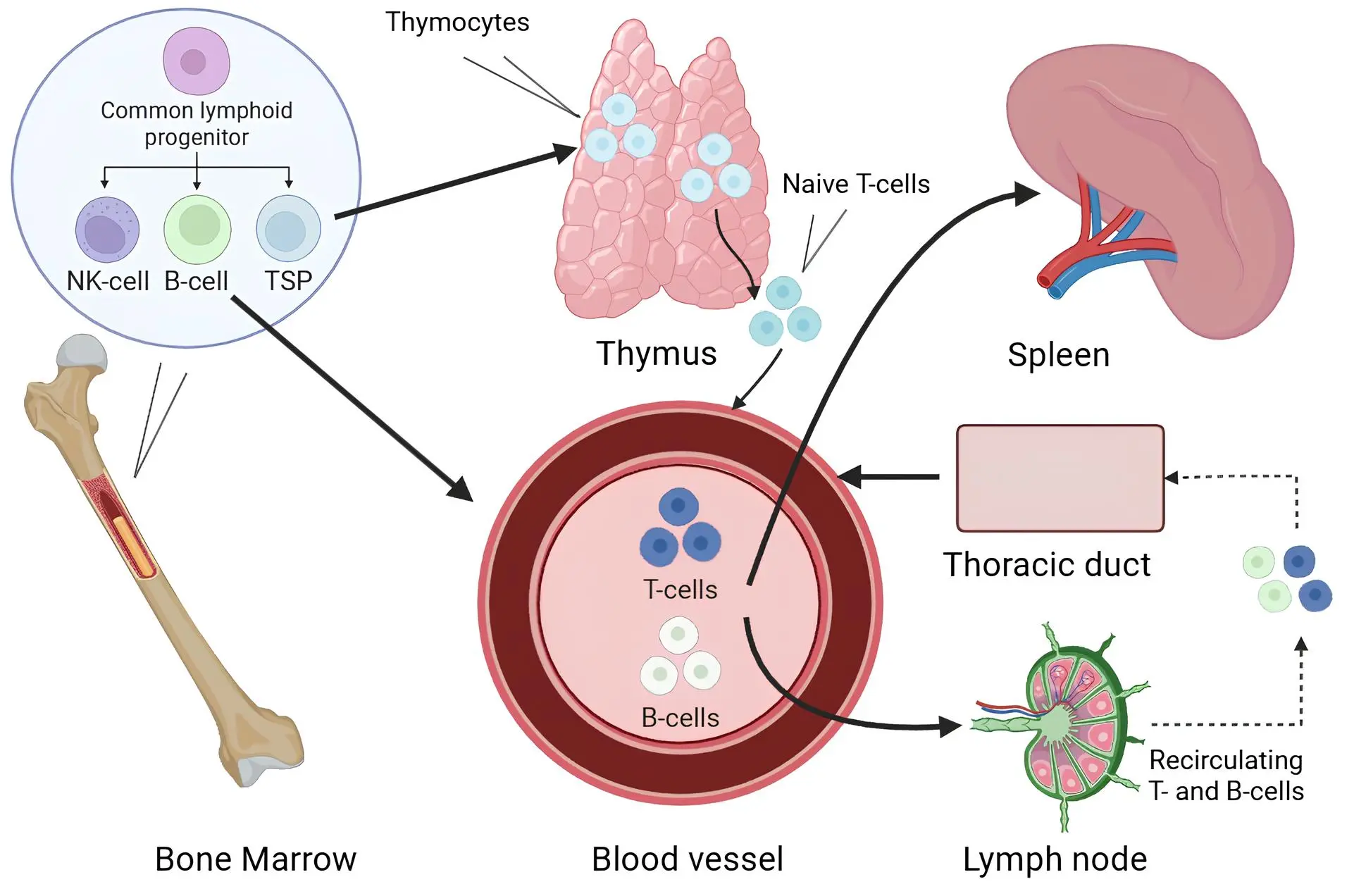

The adaptive immune system is organised as a functional axis comprising the bone marrow (BM) (site of hematopoiesis), thymus (T-cell maturation), and peripheral lymphoid organs, primarily the spleen. Together, these components constitute the life cycle of immune cells, from their origin to the execution of immune responses (Figure 1). Traditionally, it has been assumed within ageing immunology that all parts of this axis undergo senescence in a relatively uniform manner. However, emerging evidence suggests that the contributions of these organs to age-related immune dysfunction are not equivalent, differing in the rate, severity, and reversibility of age-associated changes[8-11].

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the pathways of T and B lymphocytes from the bone marrow and thymus to peripheral immune organs. Created in BioRender.com. TSP: T-cell seeding progenitor.

With ageing, the BM also slows the production of T-cell progenitors, although this function can be partially restored by hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT)[12]. Also, the spleen experiences structural and functional changes, although the latest studies have revealed compensation methods by which other immune organs can partly compensate for its functions[13,14]. In contrast, age-related changes in the thymus are characterized by early involution, loss of architectural integrity, and a reduction in naive T-cells output with limited regenerative capacity[15].

Despite the systemic nature of immunosenescence, the main question remains unresolved: which organ of the immune axis is the primary and least compensable failing point? This is an important consideration for the development of targeted interventions, particularly in the context of a rapidly ageing population.

The objective of this review is to analyze age-related changes in the BM, thymus, and spleen across various animal models and in humans, with a focus on the comparative contribution of each component to systemic immunosenescence. Based on existing evidence, we propose a thymus-centric model of adaptive immune ageing, in which thymic involution is identified as the central limiting factor driving the sustained decline in adaptive immune function in older adults.

2. BM Reserve in the Context of Ageing

The BM plays a central role in shaping the immune system by continuously producing cells of the innate immune compartment and T-cell seeding progenitors (TSPs) that populate the thymus[16]. In the early stages of immunosenescence research, age-related declines in BM hematopoietic activity were considered a primary cause of diminished immune function. However, advances in HSCT have demonstrated that the BM retains a high regenerative potential even in elderly individuals[12,17].

Following HSCT, reconstitution of the T-cell compartment occurs via two different pathways: a thymus-independent (by the proliferation of mature donor and/or recipient-derived T-cells) and a thymus-dependent (involving differentiation of HSCs into TSPs, their migration to the thymus, and the generation of naive T-cells)[9,18,19]. Notably, only the thymus-dependent pathway enables the renewal of the naive T-cells repertoire, especially vulnerable component in ageing.

Thus, despite the critical role of BM in hematopoiesis, current evidence confirms its regenerative potential through HSCT. In patients treated for cancers, high-dose chemotherapy and body irradiation, often in combination with allogeneic HSCT, acutely damage bone-marrow niches and the thymic stroma and cause a sharp decline in circulating naive T-cells as well as signal joint T-cell receptor excision circle (sjTREC) levels[16,18,19]. Donor-derived hematopoiesis usually recovers within weeks to months after transplantation, whereas thymus-dependent production of new naive T-cells is much slower and often remains incomplete, so patients rely on peripheral expansion of residual T-cells and remain at increased risk of severe infections and relapse, thereby shifting the focus toward the thymus as the principal limiting factor in the restoration of adaptive immunity[17-19].

3. The Thymus and the Limits of Adaptive Immune Regeneration

The thymus is the adaptive immune system organ that produces naive T-cells. It consists of cortical and medullary zones, in which the thymocytes pass through differentiation, selection, and maturation.

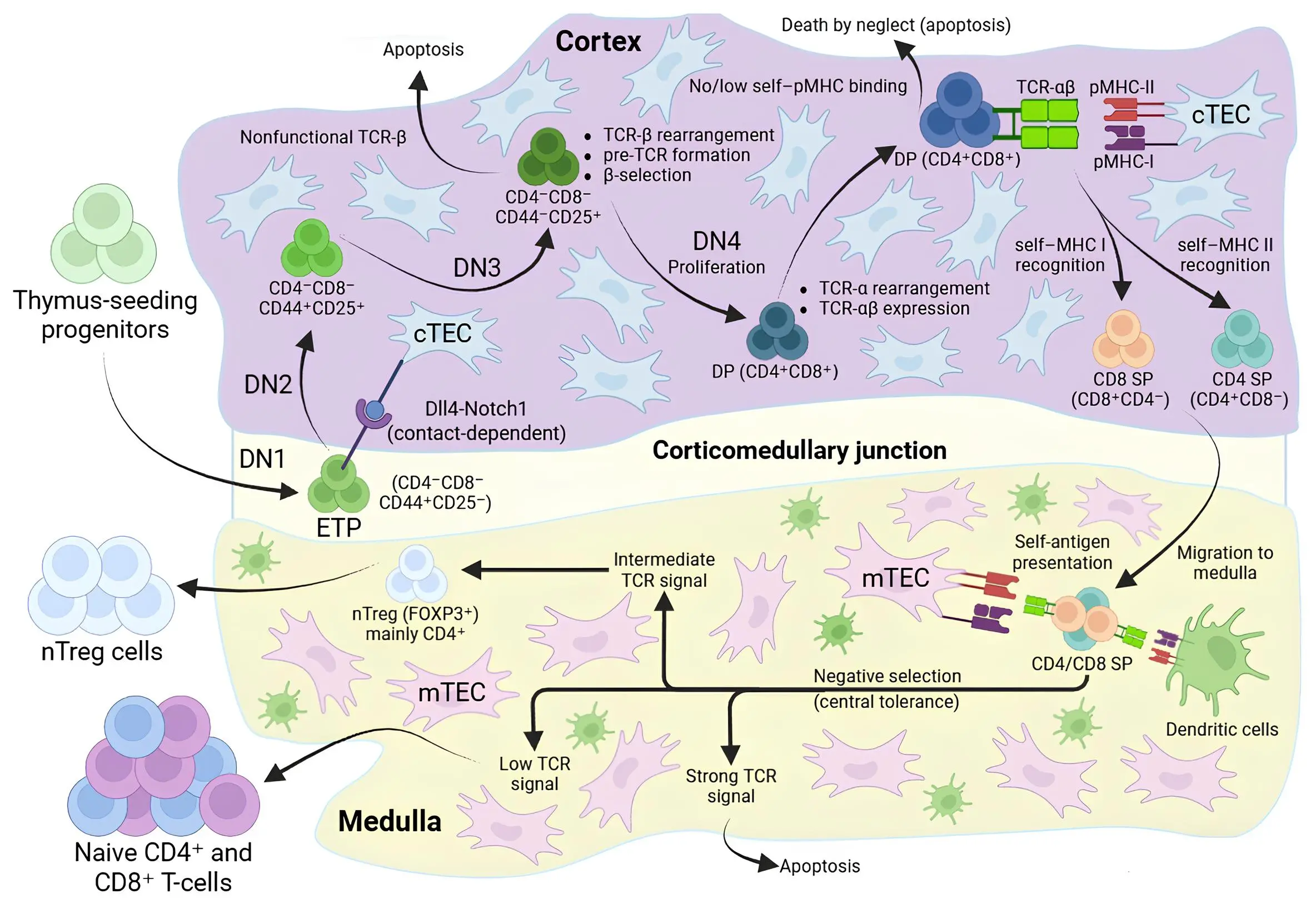

TSPs migrate from BM to the corticomedullary junction of the thymus via the bloodstream. There they interact with thymic epithelial cells (TECs) expressing the ligand Dll4, which engages the Notch1 receptor and drives their differentiation into the T-cell lineage, generating a pool of early T-cell progenitors (ETPs) corresponding to the DN1 (CD4-CD8-) stage[20]. ETPs then migrate into the cortical region, where, under the influence of IL-7, Notch signalling and other microenvironmental factors, they progress through the DN2 and DN3 stages. At these stages, the T-cell receptor (TCR)-β chain is rearranged and expressed and the pre-TCR complex is formed; cells that fail to express a functional TCR-β chain are eliminated. Successful cells enter the DN4 stage, undergo vigorous proliferation, and start to express the co-receptors CD4 and CD8, becoming double-positive (DP; CD4+CD8+) thymocytes[21].

DP thymocytes complete TCR-α rearrangement, thereby forming a fully assembled TCR-αβ, and are tested for their ability to recognize self-MHC complexes. Cells that do not interact with self-MHC die by “death by neglect”. Cells that recognize self-MHC survive and proceed to lineage choice between CD4 and CD8: cells that interact more effectively with MHC-II complexes stabilize CD4 expression and become CD4+ single-positive (SP), whereas cells with preferential recognition of MHC-I become CD8+ SP. Thus, in the cortical region of the thymus, CD4/CD8 lineages are specified, but without final checking for autoreactivity[21].

After positive selection, CD4+ and CD8+ SP thymocytes migrate to the medullary region. Medullary thymic epithelial cells and dendritic cells present tissue-specific self-antigens (through the expression of AIRE, Fezf2 and other regulators)[22]. Cells that strongly recognize these self-antigens receive a strong TCR signal and undergo apoptosis. Clones with an intermediate response to self-antigens adopt a natural regulatory T-cell (nTreg) fate and begin to express FOXP3 (mainly CD4+). Once they have left the thymus, nTregs circulate and populate peripheral lymphoid organs, where they suppress the activation of autoreactive and excessively activated effector T-cells (through secretion of IL-10 and TGF-β), thereby contributing to the maintenance of peripheral immune tolerance and limiting chronic inflammation. Cells that successfully pass both positive and negative selection and are not redirected into the nTreg lineage leave the thymus as mature naive CD4+ or CD8+ T-cells, forming the naive T-cells pool in peripheral immune organs[20,21] (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Overview of thymocyte development and central tolerance in the thymus. Created in BioRender.com. TEC: thymic epithelial cell; mTEC: medullary thymic epithelial cell; ETP: early T-cell progenitor; TCR: T-cell receptor; DP: double-positive; SP: single-positive; nTreg: natural regulatory T-cell.

Thymic involution begins early in life, accelerates during puberty, and is marked by a progressive decline in the number of TECs, disruption of corticomedullary architecture, and replacement of functional tissue with lipid stroma[15]. Studies in mice and humans have shown that the number of ETPs drops within the first and sixth months of life, respectively. This is attributed to both a reduction in TSPs in the BM and suppressed expression of critical signaling molecules such as Dll4 and IL-7 within cortical and medullary TECs[9-11]. As a result, naive T-cells output decreases and T-cells repertoire diversity contracts. In parallel, impairment of medullary tolerance mechanisms during age-related thymic involution facilitates the escape and peripheral expansion of self-reactive T-cell clones, which together fuel inflammageing and increase autoimmunity risk in older individuals[23,24].

Despite the significant structural and functional decline, thymic activity does not disappear completely in adulthood. sjTREC-based quantification of recent thymic emigrants in cohorts of older adults aged 60-100 years shows that a low but measurable thymic output persists into the eighth and ninth decades of life, and only undergoes a marked additional decline in the tenth decade, indicating ongoing generation of naive T-cells from a heavily involuted thymus. However, this residual thymopoiesis is quantitatively insufficient to restore pre-involution levels of naive T-cells numbers and diversity, in the context of clonal expansions and antigenic exposure[25].

Thymic involution is not driven by a single factor but results from the synergistic action of several interrelated mechanisms:

• Hormonal changes: The rise in sex hormone levels during puberty, particularly androgens, initiates accelerated thymic involution. Androgens suppress the expression of TEC differentiation regulators (FOXN1, Dll4, Ccl25), thereby disrupting the thymic microenvironment. It has been shown that castration in rodents partially restores thymic structure and function, indicating the reversibility of the process under reduced hormonal pressure[26].

• Infectious burden: Acute and chronic infections can damage the thymus through both direct and indirect mechanisms. Direct infection of thymocytes and TECs by certain viruses, bacteria or parasites induces apoptosis and local tissue disruption, leading to loss of thymic cellularity[27]. Indirectly, infection-associated systemic inflammation - with elevated TNF-α, IL-6, IL-33, IFN-α/β and glucocorticoids-suppresses IL-7 and MHC-II expression in TECs, impairs antigen presentation and thymocyte selection, and cumulatively accelerates age-related thymic involution, even when pathogen replication within the thymus itself is limited[27-29].

• Oxidative stress: Reactive oxygen species, iron accumulation, and the initiation of ferroptosis cause damage to both TECs and thymocytes. In ageing, expression levels of GPX4, METTL3, and the regulatory factor Nrf2 are reduced, further aggravating tissue damage[30,31].

At the cellular and molecular level, aged TECs are characterized by a reduced proliferative capacity and increased susceptibility to apoptosis, along with a decline in the expression of thymopoetic and tolerance-promoting factors. In both mice and humans, the aged thymic epithelium shows lower expression of IL-7, Dll4, and Ccl25, reduced MHC-II and co-stimulatory molecule expression, and impaired induction of AIRE- and Fezf2-dependent tissue-restricted antigens, which collectively limit support for thymocyte differentiation, positive selection, and efficient medullary negative selection[32].

These mechanisms reinforce each other, leading to a reduction in FOXN1 expression (the master transcription factor essential for TEC function and proliferation). The decline of FOXN1 destabilizes the thymic niche for T-cell maturation, and it is difficult to reverse under physiological conditions[32]. Nevertheless, several experimental and early clinical approaches, including sex-steroid ablation and cytokine- or growth factor-based strategies (such as IL-7 and keratinocyte growth factor), as well as enforced FOXN1 expression in TECs, have demonstrated partial regeneration of the aged thymus, with recovery of thymic architecture, TEC cellularity and naive T-cells output[33,34]. These data indicate that age-related thymic involution, while profound, retains a degree of plasticity that can be therapeutically exploited, although safe translation of these strategies to humans remains technically and clinically challenging.

Clinical data on thymectomy during cardiac surgery underline the role of the thymus in sustaining adaptive immunity. Children who undergo complete thymectomy show long-lasting reductions in naive CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell counts, lower sjTREC levels and oligoclonal expansion of memory T-cells many years after surgery, consistent with features of premature immune ageing[35,36]. In adults, thymectomy is associated with reduced production of new T-cells, a proinflammatory cytokine profile and an increased long-term risk of cancer, autoimmunity and all-cause mortality when compared with matched surgical controls[37]. Together, these observations indicate that loss of thymic tissue at any age imposes a durable constraint on renewal of the naive T-cells repertoire and on maintenance of immune homeostasis.

In the context of diminished naive T-cells output, the immune system increasingly relies on memory T-cells. However, these cells exhibit reduced specificity and signs of exhaustion, limiting their capacity to adapt to new antigens and placing additional functional stress on peripheral lymphoid organs, including the spleen.

4. Spleen and Age-Related Disorganization

The spleen is a central peripheral organ of the immune system responsible for immune cell recirculation, pathogen clearance, and the initiation of adaptive immune responses. Morphologically, it is divided into red pulp, which is involved in blood filtration and phagocytosis, and white pulp, which contains the activation zones for T and B lymphocytes, the periarteriolar lymphoid sheaths (PALS) and follicles, respectively[32].

With age, the spleen undergoes numerous structural and functional changes. Animal experiments have shown a reduction in the efficiency of phagocytosis in the red pulp and a decrease in the iron-regulating activity of macrophages[38,39]. They mainly affect innate immunity and have a comparably weak effect on adaptive immunity.

More critical for the adaptive compartment are age-related changes in the white pulp: lymphoid tissue volume decreases, the spatial organization of T- and B-cell zones becomes disrupted, and the expression of chemokines (Ccl19, Ccl21) required for proper localization and migration of immune cells is reduced[39]. These structural alterations impair antigen presentation and limit the activation of naive T-cells within the PALS. In the context of an age-associated decline in thymic output of naive T-cells, such disorganization further compromises the initiation of primary T-cell responses.

Nonetheless, splenic disorganization does not result in a complete loss of immune function. A number of compensatory mechanisms enable partial redistribution of splenic functions. For example, after splenectomy, CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells migrate to the mesenteric lymph nodes, where they retain their memory functionality and still provide immunity towards the second-order infections[13,40]. Additionally, the BM can support the proliferation of memory CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells and serves as a critical niche for the differentiation of plasmablasts into long-lived plasma cells[16,41].

Thus, while the spleen plays an important role in sustaining adaptive immune responses, its age-related dysfunction or even complete loss does not eliminate immune protection, as other organs, including the BM, lymph nodes, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT), and liver can redistribute and compensate for its functions. In contrast, no physiological or clinically established mechanisms currently exist to restore thymic function. The decline in naive T-cells production initiates a cascade of irreversible systemic changes in the immune system, leading to near-total failure. This weakness positions the thymus as a prime target for regenerative strategies aimed at slowing or reversing the processes of immune ageing.

5. Prospects for Restoring the Central Component of Adaptive Immunity

Multiple strategies, including genetic, pharmacological, and bioengineering approaches, aim to slow or reverse thymic involution. Several demonstrate preclinical efficacy, though human translation remains nascent and will require attention to safety (autoimmunity risk), delivery, and endpoints.

One key avenue is the modulation of FOXN1 expression, the master transcription factor regulating the differentiation and maintenance of TECs. In murine models, upregulation of FOXN1 has been shown to restore thymic architecture, enhance the output of naive T-cells, and activate thymic function in aged animals[18].

Among pharmacological strategies, androgen inhibition has shown validated efficacy by reducing hormonal pressure on the thymus. In clinical contexts (e.g., goserelin), increases in markers of naive T‑cell have been observed[26,42]. However, durability, optimal timing (intermittent vs continuous), and adverse effects require careful balancing in older adults.

Another promising approach is the administration of regulatory signaling molecules that support TEC survival and proliferation. Recombinant RANKL has attracted attention due to its ability to enhance thymic organization and improve both vaccine responsiveness and antitumor immunity in murine models[43].

Biotechnological methods are also actively being explored, such as the creation of organoids that reproduce the microenvironment of the thymus and the use of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) that have been programmed to express FOXN1, which, upon grafting, can give rise to functional thymic tissue[44]. Additionally, small molecules and signaling pathways such as Wnt, Notch, and BMP4 are being explored for their capacity to activate in situ regenerative processes[45-47].

Recently, a novel regulator fibroblast growth factor (FGF21), was identified as being expressed in TECs of ageing mice. Local expression of FGF21 prevented fatty degeneration, preserved corticomedullary structure, and restored naive T-cells production[48]. However, this method relies on gene modification, which currently limits its clinical translation.

Early-phase clinical trials of recombinant human IL-7 in HIV-infected individuals have shown expansion of circulating naive and central memory CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells, higher Ki-67 expression, increased sjTRECs content, and broadening of the TCR repertoire for up to 12 months after a short course of injections[49].

However, in these studies, IL-7 treatment was associated with increase plasma HIV RNA levels, underscoring the need for careful virological monitoring. At the same time, cytokine-driven expansion of T-cells and enforced thymic regeneration must be balanced against safety concerns: incomplete or dysregulated negative selection in an expanding thymus, particularly when FOXN1, Notch, RANKL or Wnt pathways are chronically stimulated, could facilitate the escape of autoreactive clones and increase autoimmunity risk[24,50]. Long-term activation of growth- and survival-promoting pathways (FOXN1, FGF21, Wnt, Notch) or the use of gene-modified TECs and iPSC-derived thymic organoids may also carry oncogenic and immunogenic potential[50,51]. These thymus-targeted strategies are summarized in Table 1.

| Intervention | Model | Effect on thymus | Limitations |

| FOXN1 upregulation in TECs | iFOXN1 mice | Restores thymic architecture, increases TEC cellularity and naive T-cells output[34] | Requires gene delivery to TECs; long-term safety and oncogenic risk of FOXN1 overexpression remain unknown[34,50] |

| Androgen inhibition | Rodents (chemical/surgical castration)[18,42]; Tumor-bearing/HSCT-related mouse models and androgen blockade[26] | Reverses age-related thymic atrophy in rodents; increases thymic size and cellularity, restores corticomedullary structure and markers of naive T-cells output[26,42] | Benefits may be transient; optimal timing is unclear; systemic hypogonadism with metabolic, skeletal and endocrine adverse effects[26,42] |

| RANKL administration | Male Rats (12-15 months and 2,5 months)[43] | Increases thymic cellularity and naive T-cells output, improves vaccine responses and antitumour immunity in old mice[43] | Systemic RANKL exposure may affect other RANK-expressing tissues; long-term effects on autoimmunity and neoplasia are unknown[43] |

| Modulation of Notch/Wnt/BMP4 signalling | Mouse and embryonic TEC models; mechanistic studies of Notch/Wnt /BMP4-mediated regeneration | Supports TEC homeostasis, promotes thymic regeneration, enhances thymocyte differentiation and thymopoiesis[45-47] | Notch and Wnt pathways acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and other neoplasms [50]; disturb negative selection and increase oncogenic risk[45-47,50] |

| FGF21 | Mice with FGF21 over expression[48] | Delays age-related thymic involution, reduces fatty degeneration, preserves corticomedullary structure[48] | Current approaches rely on gene modification or high-dose FGF21; systemic metabolic effects and long-term safety are unclear[48] |

| Thymus organoids and iPSC-derived TEC/thymic grafts | Human iPSC-based in vitro TEC/thymus models[44] | Generate thymus epithelial microenvironments that support TEC differentiation, offering a platform for personalised thymic replacement[44] | iPSC-derived products carry tumourigenic and immunogenic risks that require strict control[44,51] |

| IL-7 therapy | HIV-infected adults[49] | Increases circulating naive and central memory T-cells, raises Ki-67 and broadens the TCR repertoire for up to 12 months after a short course of injections[49] | Associated with increases in plasma HIV RNA, indicating expansion of infected clones[49]; long-term safety and clinical benefit remain uncertain; cytokine-driven T-cell expansion may destabilise pathogen control or autoimmunity[49] |

TECs: thymic epithelial cells; HSCT: hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; RANKL: receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand; BMP4: bone morphogenetic protein 4; FGF: fibroblast growth factor; iPSC: induced pluripotent stem cell; IL: interleukin; TCR: T-cell receptor.

Despite impressive preclinical results, the translation of these strategies into clinical practice remains unresolved. We propose that comparative analysis across species could be the key to overcoming this challenge.

6. Comparative Analysis of Immune Ageing Across Species

Cross-species analysis of animal models is essential for testing hypotheses related to systemic immune ageing. Despite morphological and physiological differences between species, mice, dogs, non-human primates (NHPs), and humans exhibit common patterns of thymic involution, naive T-cells depletion, and impaired immune responses. These parallels help identify universal ageing mechanisms and determine the translational relevance of each model.

6.1 Mice

Laboratory mice are the dominant model in the exploration of age-related thymic involution because they have high genetic homogeneity, a short lifespan (2-3 years), and a high potential for molecular manipulation. In mice, the mass of the thymus is greatest by week 4-5, and the process of involution can start as early as week 6, making it possible, through a compressed time frame, to see age-related changes[52]. The thymic architecture, including the distinction between cortical and medullary zones, closely resembles that of humans.

The murine spleen is functionally similar to the human spleen, although mice retain the capacity for extramedullary hematopoiesis, which could provide additional resilience in adaptive immune responses during ageing. Also, murine BM maintains hematopoietic activity in long bones into advanced age, a feature not observed in humans[53,54].

Therefore, while mice are ideally suited for investigating fundamental mechanisms of thymic involution, interspecies differences such as persistent hematopoiesis and a shortened immune maturation window limit the extrapolation of findings to humans.

6.2 Dogs

Dogs serve as valuable models in ageing research due to their physiological and immunological similarities to humans. Living in environments comparable to those of humans, they exhibit parallel ageing patterns, including immune decline, chronic inflammation, and reduced vaccine efficacy. This makes them particularly useful for assessing the environmental impacts on human ageing.

Thymic involution in dogs starts between the ages of 6 and 12 months, with gradual activity reduction between the ages of 1 and 5 years[55]. The organ’s mass and rate of involution vary by breed, offering additional opportunities to study the influence of genetic factors. sjTREC-based analyses in Labrador retrievers and other breeds demonstrate a decline in thymic output during early adulthood, with low but detectable sjTREC levels in some geriatric dogs and steeper declines in short-lived large breeds than in long-lived small breeds, linking thymic function to breed-specific longevity[55].

The spleen in dogs possesses strong storage functions due to the presence of smooth muscle fibers in the capsule, and the PALS zone is smaller in volume, which may reflect differences in adaptive immune architecture[53].

Similarly, canine BM undergoes age-related changes similar to those observed in humans, including decreased cellularity, fatty infiltration, and reduced regenerative capacity. Senior and geriatric dogs show classical features of immunosenescence, including altered lymphocyte subsets, markers of inflammageing, and reduced antibody titres following core vaccination[56,57].

These parallels make dogs particularly well-suited for evaluating regenerative strategies targeting the ageing immune system. However, compared to mice and other well-documented models, studies on dogs remain limited, which hinders the broader use of dogs in advancing ageing research.

6.3 NHPs

NHPs are increasingly considered in ageing research due to their physiological homology with humans. Additionally, age-related diseases in NHPs progress along paths that are generally similar to those in humans[58,59]. Analysis, nonetheless, of ageing-related modifications on the immune system is characterized by multiple differences that restrict the straightforward extrapolation.

In terms of trajectory with age, the BM of NHPs is similarly predictive, with fatty infiltration and a movement toward myelopoiesis[60]. Thymic involution is earlier in the NHP, and variability in the repertoire of the MHC class I makes transferability of information on CD8+ T-cell specificity difficult. Additionally, it has been frequently reported that NHPs exhibit deviations in CDR3 profiles in peripheral blood due to CD8-biased repertoires, a high frequency of double-positive T-cells (up to 10-15%), and a reduced CD4/CD8 ratio[61]. These features hinder the direct extrapolation of NHP data to humans, particularly in studies involving immune response kinetics and the evaluation of antigen-specific T- and B-cell repertoires.

Thus, while biological ageing of immune organs in NHPs may occur earlier in chronological terms, specific immunological traits such as MHC I profile and a high prevalence of double-positive T-cells complicate data interpretation in the context of anti-ageing strategies. In cases in which the kinetics of lymphopoiesis or thymopoiesis are important, dogs can be a more useful translational model. In addition, the use of NHPs is limited by the expense of maintenance, the intricacies associated with invasive studies, as well as ethical requirements. However, validation of data obtained in mice and dogs helps strengthen the reliability of eventual human translation.

6.4 Humans

Although humans are the ultimate target model in clinical gerontology, direct studies of immune ageing are limited. This is due to the length of human life, the impracticality of invasive thymic interventions, and the inaccessibility of lymphoid tissues.

Thymic involution in humans begins early: after the first year of life, there is a gradual decline in mass and cellularity, which accelerates sharply during puberty. By age 40, the majority of functional thymic tissue is replaced by fat, and naive T-cells production becomes restricted[55]. Although small epithelial parts persist, their functional capacity declines year by year.

Age related splenic disorganization is observed (as in mice), with reduced lymphoid density, abnormal follicular morphology, and contraction of the marginal zone[38]. However, splenic function is compensated by the BM, liver and secondary lymphoid organs such as lymph nodes, MALT.

In humans, BM loses hematopoietic activity as early as age 30 (by approximately 40%) and by age 70 may retain only one-third of its original capacity[62]. This is accompanied by reduced proliferative potential and diminished T-cell progenitor output.

In summary, the key patterns of immune ageing in humans include a gradual decline in BM cellularity, early-onset thymic involution, structural disorganization of the spleen, and lack of splenic hematopoiesis. In mice, thymic involution is among the most rapid of all mammals, but compensatory hematopoiesis persists in both the spleen and BM. Dogs exhibit physiology closer to that of humans; however, the timing and rate of thymic involution vary by breed, and the spleen has a capacity to store blood. NHPs experience thymic involution earlier, and their BM exhibits an earlier myeloid shift. The splenic marginal zone retains its functionality for a longer period.

From a translational standpoint, mice are optimal for investigating molecular mechanisms; dogs serve as an intermediate model for testing interventions in long-lived species; NHPs provide anatomical proximity but exhibit distortions in ageing kinetics. Humans remain the ultimate but least accessible model due to their long lifespan, ethical constraints, and the impracticality of invasive procedures. Cross-species features of immune ageing are summarized in Table 2.

| Species | Onset of thymic involution | Thymus | Bone marrow | Spleen | Translational note |

| Mouse | Peak mass at 4-5 weeks; involution from ~6 weeks[52] | Human-like cortico–medullary structure; very rapid involution; residual thymopoiesis in old age[52] | Persistent hematopoiesis in long bones; extramedullary hematopoiesis[53,54] | Similar to human but supports extramedullary hematopoiesis[53,54] | Excellent for mechanisms and intervention screening; short lifespan and persistent hematopoiesis limit extrapolation |

| Dog | Starts at 6-12 months; marked decline between 1-5 years[55] | Thymic mass and involution rate vary by breed; sjTREC decline in early-mid adulthood; some geriatric dogs retain low thymic output[55] | Age-related decreased cellularity, fatty infiltration and reduced regenerative capacity, similar to humans | Storage spleen with smooth muscle capsule; strong blood-storage capacity; smaller PALS volume[53] | Physiology close to humans; natural environment and spontaneous disease make them suitable for testing immune-ageing interventions; constrained by breed variation and limited longitudinal datasets[55,57,58] |

| Non-human primate | Earlier than in humans (juvenile/early adult)[56,59-61] | Early, pronounced involution; diverse MHC I and CD8-biased repertoires; high frequency of CD4+CD8+ T-cells and altered CDR3 profiles[61] | Fatty infiltration and myeloid shift similar to humans[60] | Splenic marginal zone and architecture remain functional longer; some extramedullary hematopoiesis[59-61] | Closest anatomical/physiological model; good for late-stage validation; repertoire differences, cost and ethics restrict large-scale or invasive ageing studies |

| Human | Begins after first year; accelerates at puberty; by ~40 years mostly fatty replacement[53] | Progressive loss of thymic mass and cellularity; small epithelial islands with declining function; chronic reduction in naive T-cells output and repertoire diversity[53] | Cellularity drops from ~30 years; by ~70 years ~one-third of original capacity; reduced proliferative potential and T-cell progenitor output[53,62] | Age-related disorganisation, reduced lymphoid density and marginal zone contraction; no splenic hematopoiesis; partial compensation by bone marrow, liver, lymph nodes and MALT[38,53] | Ultimate target species; translation constrained by long lifespan, ethics and limited access to thymus and lymphoid tissues |

sjTREC: signal joint T-cell receptor excision circle; PALS: periarteriolar lymphoid sheaths; MALT: mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue.

7. Current Challenges

Despite significant progress in understanding the mechanisms of immune ageing and developing potential strategies to slow it down, the clinical implementation of thymus regeneration approaches faces several fundamental limitations.

One of the primary issues is the thymus’s limited capacity for regeneration in the adult organism. With age, the number of functional TECs, which form the organ’s microenvironment, declines sharply. This makes them a poor source for cell-based therapies. Attempts to culture TECs in vitro, particularly under standard 2D culture conditions, encounter phenotypic instability: the cells lose key markers, exhibit diminished functionality, and are poorly expandable[63].

Meanwhile, the problem of constructing the thymus in three dimensions still remains unsolved. Although experiments on decellularized scaffolds and repopulating with cells have been promising, practical disadvantages remain: nonuniform distribution of the cells, low permeability, weak vascularization, and graft size variability all limit the efficiency of such approaches. Novel 3D scaffolds, including silk fibroin-based structures and self-assembling peptide hydrogels such as EAK16-II, demonstrate potential, but require further standardization and refinement before clinical application[63].

Another problem is the limited availability of suitable source cells. Differentiation from fibroblasts and the use of iPSCs have thus far failed to produce mature TECs capable of reconstituting a functional corticomedullary zone and supporting effective T-cell selection[63].

Finally, integrating a bioengineered thymus into the body presents serious barriers. These include the need to establish a vascular network (angiogenesis), ensure immunological tolerance of the graft, and recreate the mechanisms of negative selection that prevent autoimmune responses. Without meeting these conditions, stable and safe thymus transplantation remains challenging[64].

In summary, despite active progress, the thymus remains a highly challenging organ to regenerate. This underscores its unique status as the least recoverable part of the immune axis and supports the need for strategies toward the conservation of thymic function before the irreversible age-related depreciation occurs.

8. Conclusion and Future Perspectives

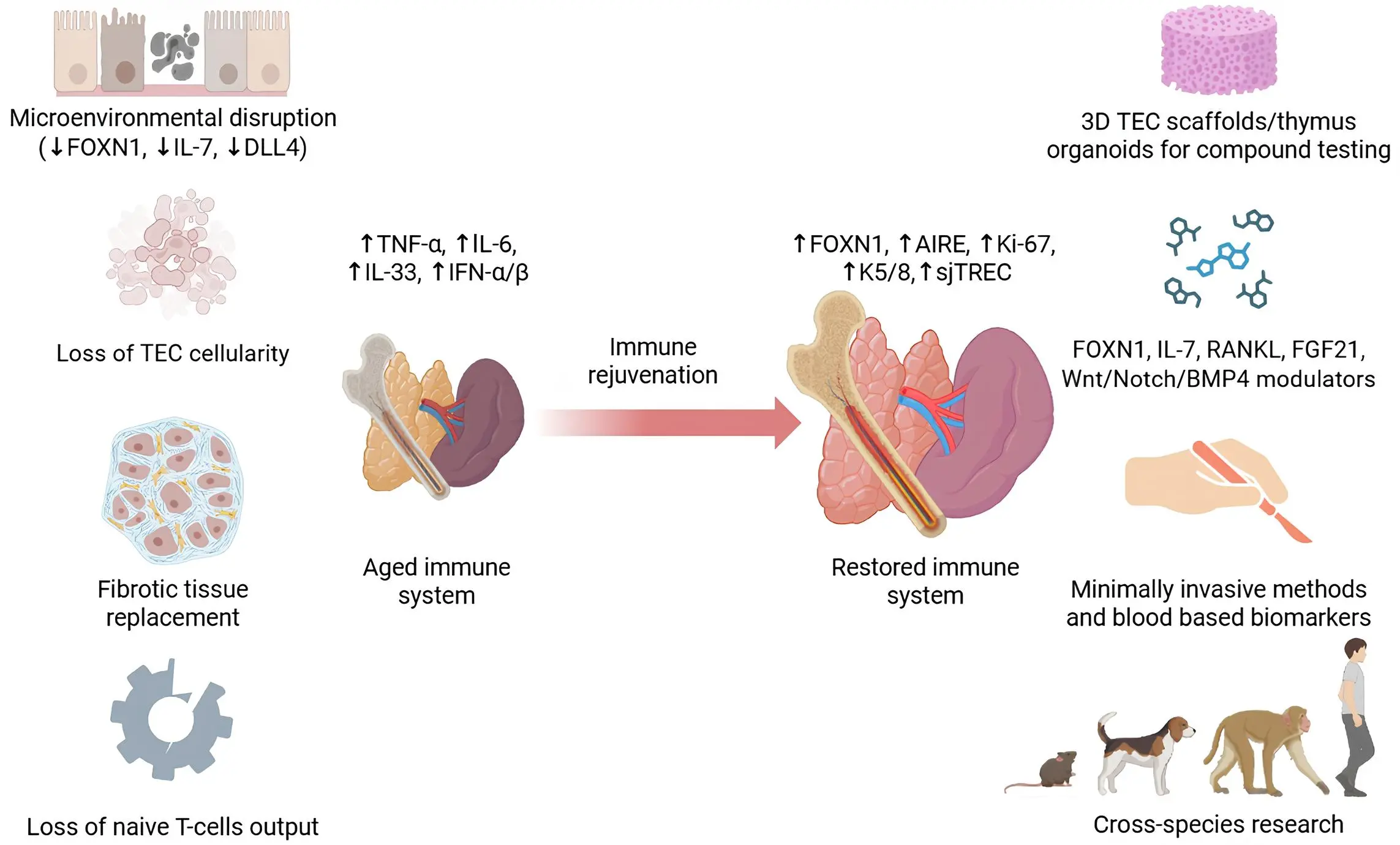

Age-related thymic involution is a central constraint on adaptive immune plasticity: it reduces de novo naive T‑cells production, contracts TCR repertoire diversity, and contributes to vulnerability to infections and malignancies in older adults. Despite advancements, durable restoration of thymic function faces unresolved challenges, including limited sources of viable TECs, the complexity of recapitulating three-dimensional organ architecture, and the difficulty of integrating engineered tissue into the native immune environment. These challenges underscore the need for a staged approach focusing on early preservation, targeted niche support, and stepwise bioengineering advances.

Promising directions include multifactorial models of thymic ageing, using 3D scaffolds and simulated stress environments to test novel molecules, biologics, and gene/cell therapies that stabilize TECs and sustain the expression of key regulators such as FOXN1. In parallel, cross-species studies, particularly those involving dogs and NHPs as intermediate models, offer valuable opportunities for identifying universal mechanisms of immune ageing. These models can accelerate the development of therapeutic approaches targeting immune ageing in humans (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Schematic of age-related immune system degeneration and strategies for thymus-centric immune rejuvenation. Created in BioRender.com. TEC: thymic epithelial cell; FGF: fibroblast growth factor; sjTREC: signal joint T-cell receptor excision circle; IL: interleukin; IFN: interferon; TNF: tumor necrosis factor; AIRE: autoimmune regulator; RANKL: receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand.

From a systems perspective, BM and peripheral organs show meaningful plasticity, whereas the thymus remains the least compensable node. This supports the view of the thymus as the primary failing point within the immune axis and a central therapeutic target in combating immunosenescence. The thymus-centric model redefines the understanding of uniform immune ageing and offers a clear framework for the development of targeted interventions to extend immune health in older adults.

Authors contribution

Mironenkov A: Conceptualization, writing-original draft.

Zhu JK, Lyu YX: Conceptualization, writing-review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

Mironenkov A, Zhu JK, and Lyu YX are supported by Southern University of Science and Technology, the Guangdong Science and Technology Program (2024B1111130001), and the Shenzhen Science and Technology Program(KJZD20240903102703005). Lyu YX also acknowledges support from the Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (JCYJ20240813094515020) and the TimePie Longevity Research Grant Program.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

References

-

1. Hoffman JM, Creevy KE, Franks A, O’Neill DG, Promislow DEL. The companion dog as a model for human aging and mortality. Aging Cell. 2018;17(3):e12737.[DOI]

-

2. Müller L, Andrée M, Moskorz W, Drexler I, Walotka L, Grothmann R, et al. Age-dependent immune response to the BioNTech/Pfizer BNT162b2 coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(11):2065-2072.[DOI]

-

3. Lei J, Ji Z, Qu J. Homeostatic medicine: Innovative practices and future prospects of aging intervention. Oral Sci Homeost Med. 2025;1(1):9610021.[DOI]

-

4. Qi S, Li J, Gu X, Zhang Y, Zhou W, Wang F, et al. Impacts of ageing on the efficacy of CAR-T cell therapy. Ageing Res Rev. 2025;107:102715.[DOI]

-

5. Hou C, Wang Z, Lu X. Impact of immunosenescence and inflammaging on the effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer Pathog Ther. 2024;2(1):24-30.[DOI]

-

6. Noll JH, Levine BL, June CH, Fraietta JA. Beyond youth: Understanding CAR T-cell fitness in the context of immunological aging. Semin Immunol. 2023;70:101840.[DOI]

-

7. Yin J, Song Y, Fu Y, Jun W, Tang J, Zhang Z, et al. The efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors is limited in elderly NSCLC: A retrospective efficacy study and meta-analysis. Aging (Albany NY). 2023;15(24):15025-15049.[DOI]

-

8. Sun L, Su Y, Jiao A, Wang X, Zhang B. T cells in health and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):235.[DOI]

-

9. Srinivasan J, Vasudev A, Shasha C, Selden HJ, Perez E Jr, LaFleur B, et al. The initial age-associated decline in early T-cell progenitors reflects fewer pre-thymic progenitors and altered signals in the bone marrow and thymus microenvironments. Aging Cell. 2023;22(8):e13870.[DOI]

-

10. Deng Y, Peng Z, Ming K, Qiao X, Ye B, Liu Y, et al. Single-cell analysis of human thymus and peripheral blood unveils the dynamics of T cell development and aging. Nat Aging. 2025;5(12):2494-2513.[DOI]

-

11. Weerkamp F, de Haas EFE, Naber BAE, Comans-Bitter WM, Bogers AJJC, van Dongen JJM, et al. Age-related changes in the cellular composition of the thymus in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115(4):834-840.[DOI]

-

12. Gaudeaux P, Moirangthem RD, Bauquet A, Simons L, Joshi A, Cavazzana M, et al. T-cell progenitors as a new immunotherapy to bypass hurdles of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Front Immunol. 2022;13:956919.[DOI]

-

13. Turner VM, Mabbott NA. Influence of ageing on the microarchitecture of the spleen and lymph nodes. Biogerontology. 2017;18(5):723-738.[DOI]

-

14. Kim MT, Harty JT. Splenectomy alters distribution and turnover but not numbers or protective capacity of de novo generated memory CD8 T-cells. Front Immunol. 2014;5:568.[DOI]

-

15. Liang Z, Dong X, Zhang Z, Zhang Q, Zhao Y. Age-related thymic involution: Mechanisms and functional impact. Aging Cell. 2022;21(8):e13671.[DOI]

-

16. Schirrmacher V. Bone marrow: The central immune system. Immuno. 2023;3(3):289-329.[DOI]

-

17. Sophie S, Yves B, Frédéric B. Current status and perspectives of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2022;11(5):461-477.[DOI]

-

18. Velardi E, Tsai JJ, van den Brink MRM. T cell regeneration after immunological injury. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21(5):277-291.[DOI]

-

19. Krenger W, Blazar BR, Holländer GA. Thymic T-cell development in allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2011;117(25):6768-6776.[DOI]

-

20. Kashiwagi M, Figueroa DS, Ay F, Morgan BA, Georgopoulos K. A double-negative thymocyte-specific enhancer augments Notch1 signaling to direct early T cell progenitor expansion, lineage restriction and β-selection. Nat Immunol. 2022;23(11):1628-1643.[DOI]

-

21. Klein L, Kyewski B, Allen PM, Hogquist KA. Positive and negative selection of the T cell repertoire: What thymocytes see (and don’t see). Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14(6):377-391.[DOI]

-

22. Takaba H, Takayanagi H. The mechanisms of T-cell selection in the thymus. Trends Immunol. 2017;38(11):805-816.[DOI]

-

23. Thomas R, Wang W, Su DM. Contributions of age-related thymic involution to immunosenescence and inflammaging. Immun Ageing. 2020;17:2.[DOI]

-

24. Coder BD, Wang H, Ruan L, Su DM. Thymic involution perturbs negative selection leading to autoreactive T-cells that induce chronic inflammation. J Immunol. 2015;194(12):5825-5837.[DOI]

-

25. Mitchell WA, Lang PO, Aspinall R. Tracing thymic output in older individuals. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;161(3):497-503.[DOI]

-

26. Polesso F, Caruso B, Hammond SA, Moran AE. Restored thymic output after androgen blockade participates in antitumor immunity. J Immunol. 2023;210(4):496-503.[DOI]

-

27. Luo M, Xu L, Qian Z, Sun X. Infection-associated thymic atrophy. Front Immunol. 2021;12:652538.[DOI]

-

28. Xu L, Wei C, Chen Y, Wu Y, Shou X, Chen W, et al. IL-33 induces thymic involution-associated naive T-cell aging and impairs host control of severe infection. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):6881.[DOI]

-

29. Démoulins T, Baron ML, Gauchat D, Kettaf N, Reed SJ, Charpentier T, et al. Induction of thymic atrophy and loss of thymic output by type-I interferons during chronic viral infection. Virology. 2022;567:77-86.[DOI]

-

30. Jing H, Song J, Sun J, Su S, Hu J, Zhang H, et al. METTL3 governs thymocyte development and thymic involution by regulating ferroptosis. Nat Aging. 2024;4(12):1813-1827.[DOI]

-

31. Han H, Zhang G, Zhang X, Zhao Q. Nrf2-mediated ferroptosis inhibition: A novel approach for managing inflammatory diseases. Inflammopharmacology. 2024;32(5):2961-2986.[DOI]

-

32. Romano R, Palamaro L, Fusco A, Giardino G, Gallo V, Del Vecchio L, et al. FOXN1: A master regulator gene of thymic epithelial development program. Front Immunol. 2013;4:187.[DOI]

-

33. Velardi E, Dudakov JA, van den Brink MRM. Sex steroid ablation: An immunoregenerative strategy for immunocompromised patients. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2015;50(2):S77-S81.[DOI]

-

34. Duah M, Li L, Shen J, Lan Q, Pan B, Xu K. Thymus degeneration and regeneration. Front Immunol. 2021;12:706244.[DOI]

-

35. Cavalcanti NV, Palmeira P, Jatene MB, de Barros Dorna M, Carneiro-Sampaio M. Early thymectomy is associated with long-term impairment of the immune system: A systematic review. Front Immunol. 2021;12:774780.[DOI]

-

36. Sauce D, Larsen M, Fastenackels S, Duperrier A, Keller M, Grubeck-Loebenstein B, et al. Evidence of premature immune aging in patients thymectomized during early childhood. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(10):3070-3078.[DOI]

-

37. Kooshesh KA, Foy BH, Sykes DB, Gustafsson K, Scadden DT. Health consequences of thymus removal in adults. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(5):406-417.[DOI]

-

38. Mebius RE, Kraal G. Structure and function of the spleen. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5(8):606-616.[DOI]

-

39. Slusarczyk P, Mandal PK, Zurawska G, Niklewicz M, Chouhan K, Mahadeva R, et al. Impaired iron recycling from erythrocytes is an early hallmark of aging. Elife. 2023;12:e79196.[DOI]

-

40. Liu X, Sun Y, Su Y, Gao Y, Zhang T, Wang Q, et al. The compensatory role of T-cells from lymph nodes in mice with splenectomy. J Cell Mol Med. 2024;28(10):e18363.[DOI]

-

41. Di Rosa F, Pabst R. The bone marrow: A nest for migratory memory T cells. Trends Immunol. 2005;26(7):360-366.[DOI]

-

42. Kendall MD, Fitzpatrick FT, Greenstein BD, Khoylou F, Safieh B, Hamblin A. Reversal of ageing changes in the thymus of rats by chemical or surgical castration. Cell Tissue Res. 1990;261(3):555-564.[DOI]

-

43. Santamaria JC, Chevallier J, Dutour L, Picart A, Kergaravat C, Cieslak A, et al. RANKL treatment restores thymic function and improves T-cell-mediated immune responses in aged mice. Sci Transl Med. 2024;16(776):eadp3171.[DOI]

-

44. Pretemer Y, Gao Y, Kanai K, Yamamoto T, Kometani K, Ozaki M, et al. An iPSC-based in vitro model recapitulates human thymic epithelial development and multi-lineage specification. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):7680.[DOI]

-

45. García-León MJ, Mosquera M, Cela C, Alcain J, Zuklys S, Holländer G, et al. Abrogation of Notch signaling in embryonic TECs impacts postnatal mTEC homeostasis and thymic involution. Front Immunol. 2022;13:867302.[DOI]

-

46. Weerkamp F, Baert MR, Naber BA, Koster EE, de Haas EF, Atkuri KR, et al. Wnt signaling in the thymus is regulated by differential expression of intracellular signaling molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103(9):3322-3326.[DOI]

-

47. Wertheimer T, Velardi E, Tsai J, Cooper K, Xiao S, Kloss CC, et al. Production of BMP4 by endothelial cells is crucial for endogenous thymic regeneration. Sci Immunol. 2018;3(19):eaal2736.[DOI]

-

48. Youm YH, Horvath TL, Mangelsdorf DJ, Kliewer SA, Dixit VD. Prolongevity hormone FGF21 protects against immune senescence by delaying age-related thymic involution. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2016;113(4):1026-1031.[DOI]

-

49. Lévy Y, Sereti I, Tambussi G, Routy JP, Lelièvre JD, Delfraissy JF, et al. Effects of recombinant human interleukin 7 on T-cell recovery and thymic output in HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy: Results of a phase I/IIa randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter study. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(2):291-300.[DOI]

-

50. Staal FJ, Langerak AW. Signaling pathways involved in the development of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2008;93(4):493-497.[DOI]

-

51. Qiao Y, Agboola OS, Hu X, Wu Y, Lei L. Tumorigenic and immunogenic properties of induced pluripotent stem cells: A promising cancer vaccine. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2020;16(6):1049-1061.[DOI]

-

52. Yellayi S, Teuscher C, Woods JA, Welsh TH Jr, Tung KS, Nakai M, et al. Normal development of thymus in male and female mice requires estrogen/estrogen receptor-alpha signaling pathway. Endocrine. 2000;12(3):207-213.[DOI]

-

53. Haley PJ. The lymphoid system: A review of species differences. J Toxicol Pathol. 2017;30(2):111-123.[DOI]

-

54. O’Connell KE, Mikkola AM, Stepanek AM, Vernet A, Hall CD, Sun CC, et al. Practical murine hematopathology: A comparative review and implications for research. Comp Med. 2015;65(2):96-113.

-

55. Holder A, Mella S, Palmer DB, Aspinall R, Catchpole B. An age-associated decline in thymic output differs in dog breeds according to their longevity. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0165968.[DOI]

-

56. Pereira M, Valério-Bolas A, Saraiva-Marques C, Alexandre-Pires G, Pereira da Fonseca I, Santos-Gomes G. Development of dog immune system: From in uterus to elderly. Vet Sci. 2019;6(4):83.[DOI]

-

57. Dal’Ara P, Lauzi S, Turin L, Castaldelli G, Servida F, Filipe J. Effect of aging on the immune response to core vaccines in senior and geriatric dogs. Vet Sci. 2023;10(7):412.[DOI]

-

58. Mattison JA, Vaughan KL. An overview of nonhuman primates in aging research. Exp Gerontol. 2017;94:41-45.[DOI]

-

59. Colman RJ. Non-human primates as a model for aging. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2018;1864(9):2733-2741.[DOI]

-

60. Yu KR, Espinoza DA, Wu C, Truitt L, Shin TH, Chen S, et al. The impact of aging on primate hematopoiesis as interrogated by clonal tracking. Blood. 2018;131(11):1195-1205.[DOI]

-

61. Currier JR, Stevenson KS, Kehn PJ, Zheng K, Hirsch VM, Robinson MA. Contributions of CD4+, CD8+, and CD4+CD8+ T-cells to skewing within the peripheral T-cell receptor β chain repertoire of healthy macaques. Hum Immunol. 1999;60(3):209-222.[DOI]

-

62. Prabhakar M, Ershler WB, Longo DL. Bone marrow, thymus and blood: Changes across the lifespan. Aging health. 2009;5(3):385-393.[DOI]

-

63. Chaudhry MS, Velardi E, Dudakov JA, van den Brink MRM. Thymus: The next (re)generation. Immunol Rev. 2016;271(1):56-71.[DOI]

-

64. Markert ML, Boeck A, Hale LP, Kloster AL, McLaughlin TM, Batchvarova MN, et al. Transplantation of thymus tissue in complete DiGeorge syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(16):1180-1189.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite