Abstract

Aims: Recurrent and uncontrolled inflammation of the colon may cause inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), which are strongly associated with the onset of colitis-associated cancer (CAC). However, the molecular mechanisms linking inflammation, dysregulated growth, and tumorigenesis remain unclear. This study aims to determine the role of the N6-methyladenosine (m6A) reader YTH m6A RNA binding protein 1 (Ythdf1) in regulating colitis severity and CAC development.

Methods: Ythdf1-deficient and wild-type mice were subjected to dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced colitis to evaluate disease severity, epithelial survival, goblet cell and mucus preservation, and inflammatory signaling. m6A-dependent regulation of Jak1 mRNA and the

Results: Ythdf1 deficiency significantly worsened DSS-induced colitis, with increased epithelial damage, loss of goblet cells and mucus, impaired epithelial survival, and reduced Stat3 activation. Mechanistically, Ythdf1 recognized m6A-modified Jak1 mRNA and enhanced Jak1 protein expression, thereby maintaining the Il6-Jak1-Stat3 signaling during inflammatory stress. Despite aggravating colitis, Ythdf1 loss markedly suppressed CAC progression and reduced tumor burden.

Conclusion: Ythdf1 is a key regulator of intestinal homeostasis, maintaining the Il6-Jak1-Stat3 signaling to protect against colitis while paradoxically promoting CAC progression. These findings identify Ythdf1 as a context-dependent modulator of intestinal inflammation and tumorigenesis, highlighting its therapeutic potential in IBD and CAC.

Keywords

1. Introduction

Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are forms of human inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that involve chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract and alternating periods of remission and relapse[1], and millions of individuals are affected[2]. IBD has a strong association with colitis-associated cancer (CAC)[3], and for this reason, the successful treatment of IBD is of double importance: not only will patients with IBD see their quality of life improve, but their risk of developing CAC will be lowered. Unfortunately, there is currently no cure for Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, with current treatments being focused primarily on disease management. Therefore, novel, effective treatments for IBD are urgently required, particularly when the additional need to prevent CAC is considered.

Genetic background, immune dysregulation, disruption of the intestinal epithelial barrier and imbalances in commensal microbiota have all been implicated in the pathogenesis of IBD[1]. The integrity of the intestinal epithelial barrier is of particular relevance: the commensal bacteria in the intestinal lumen are separated from the immune system by a single layer of epithelial cells and mucus[4]. Breach of the epithelial barrier leads to microbial invasion and immune activation, and the resultant inflammation can lead to the initiation of IBD, particularly when this is a recurrent event[4]. The intestinal epithelium normally maintains its integrity through the careful orchestration of cell proliferation, self-renewal, differentiation and cell death[5]. While constitutive regeneration signalling inhibits apoptosis and promotes repair, maintaining the integrity of the intestinal epithelium and protecting against colitis, sustained and uncontrolled cell proliferation may increase the risk of hyperplasia and malignant transformation[6]. Therefore, the balance between repair/regeneration and hyperplasia/carcinogenesis merits further investigation.

Post-transcriptional modification adds a new layer of complexity to the control of mRNA metabolism and through this, to cell fate; helping cells respond more rapidly and accurately to external stimuli[7]. N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is one of the most common internal mRNA modifications in mammals, and regulates the fate and functions of target RNAs through specific reader proteins[8,9].

DSS-induced colitis and AOM/DSS-induced CAC mimic the development of clinical ulcerative colitis both histopathologically and symptomatically[23]. Here, we used DSS-induced colitis, CAC, and genetically modified models to investigate the function of the m6A reader Ythdf1 and the Stat3 pathway in intestinal epithelial homeostasis. The data suggest that Ythdf1 maintains survival and promotes proliferation of colon epithelial cells, and that this occurs via the Il-6-Jak1-Stat3 pathway. However, while this alleviates colitis, it also promotes neoplasia.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Mouse models

Ythdf1 KO mice were generated using the CRISPR–Cas9 system and a commercial service from Cyagen Biosciences (Guangzhou, China), as previously described[17]. All experimental mice were housed under specific pathogen free conditions, and littermates were used. Animal experiments were conducted in accordance with ethical and scientific standards approved by the Committee on the Use of Live Animals in Teaching and Research under protocol 2020001 of Shenzhen University, China.

2.2 Cells and regent

The human intestinal epithelial cell line HCT116 was cultured in DMEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin (PS; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). HCT116 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC®) and grown at 37 ˚C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Recombinant human IL-6 was purchased from Sino Biological Inc. (Beijing, China).

2.3 DSS-induced experimental colitis model

8-week-old mice were treated with 2.5% DSS (MW 36-50 KDa; MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA, USA) in their drinking water for 5 days, followed by 2 days of normal water. Mice were then sacrificed for analysis on day 7. Body weight, stool and bleeding were monitored daily. The overall clinical features were scored as previously described[24]: a combination of stool score (0-3), stool blood score (0-2), and overall appearance (0-2). For colitis, distal colon sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin (HE), and inflammatory infiltration (0-5), crypt damage (0-4), and ulceration (0-3) scores were determined in a double-blind manner, as previously described[25]. To investigate survival of the DSS-induced experimental colitis model, 8-week old mice received 4% DSS in their drinking water for 6 days. This was followed by normal water, and survival was monitored.

2.4 AOM/DSS-induced colitis associated cancer model

CAC models were generated as previously described, with some modifications[26]. Briefly, 10-week-old male mice were intraperitoneally injected with 10 mg/kg azoxymethane (AOM; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). After 5 days, 2% DSS was included in the drinking water for 5 days, then normal water was given for 16 days. This cycle was repeated three times. On day 92, mice were sacrificed for analysis. The polyp load was calculated as the sum of the mean diameters of all visible tumours in each mouse.

2.5 Bone marrow transplantation

Recipient WT or Ythdf1 KO male mice (10-12 weeks old) were irradiated with X-rays (9 Gy). Bone marrow cells (BMCs) were collected from non-irradiated WT and Ythdf1 KO mice as donor cells. A total of 5 × 106 BMCs per mouse were injected into the recipient mice within 4 hours of irradiation, via the tail vein. Four groups of mice received bone marrow transplantation, as follows: WT-WT, WT mice reconstituted with WT BMCs; KO-WT, WT mice reconstituted with Ythdf1 KO BMCs; WT-KO, Ythdf1 KO mice reconstituted with WT BMCs; and KO-KO, Ythdf1 KO mice reconstituted with Ythdf1 KO BMCs. Experimental colitis was induced 8 weeks after bone marrow transplantation as described above.

2.6 Colon epithelial cell isolation

Colon epithelial cells were isolated as previously described[17]. Briefly, after the mice were sacrificed, their colons were excised and opened longitudinally. Fecal matter was removed, and the mucus layer was gently scraped off. The tissues were then rinsed three times with cold PBS, cut into small fragments, and incubated in PBS containing 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, and 10 μM ROCK inhibitor

2.7 Flow cytometric analysis

Single cell suspensions from the thymus, peripheral lymph nodes, mesenteric lymph nodes, spleen and bone marrow were labelled with the following surface markers at 4 ˚C for 40 min: CD11b-APC (cat. no. 101211) and F4/80-FITC (cat. no. 123107) for macrophages, CD11b-APC (cat. no. 101211) and Ly6g-FITC (cat. no. 108405) for neutrophils, CD19-APC (cat. no. 152409) for B cells, CD11c-APC (cat. no. 117309) for dendritic cells and CD4-APC (cat. no. 100411) or CD8-FITC (cat. no. 100705) for T cells (all obtained from BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA). Cells were washed twice with FPBS (PBS with 2% FBS), and then flow cytometry was performed using the BD FACScanto II cell analyzer and FlowJo software (FlowJo 7.6, BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ USA).

2.8 Western blotting

Colon tissues or single cells were lysed in SDS lysis buffer, and the supernatant was collected and subjected to western blotting. Protein samples were loaded and separated on 8% or 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and then transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Merck KGaA). Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk and labelled with primary antibodies overnight at 4 ˚C. Blots were visualised on a Bio-Rad system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) following incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies for an hour at room temperature, Goat anti-Rabbit (1:5,000; 111-035-003) and Goat anti-Mouse (1:5,000;

2.9 RNA isolation and quantitative real time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cells or tissues with RNAiso Plus (Takara Bio, Inc., Shiga, Japan), and isolated RNAs were

2.10 m6A immunoprecipitation

Methylated RNA immunoprecipitation (MeRIP) with specific m6A antibody (Synaptic Systems, cat. no. 202003) was carried out according to a previously described protocol with some modifications[27]. Briefly, total RNA was extracted with Trizol®, saving 100 ng RNA as input, and 2 μg RNA was incubated with m6A antibody (2.5 μg) in IP buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Igepal CA-630 and 400 U/mL RNase inhibitor) at 4 ˚C overnight. Then, m6A modified RNAs were immunoprecipitated with Dynabeads® Protein A/G and eluted with elution buffer (IP buffer with 2.56 mg/ml m6A 5’monophosphate sodium) twice. The eluted RNA was extracted with Trizol® and used to synthesize cDNA by reverse transcription. qRT-PCR analysis of Jak1 was conducted using forward primer:

5'-TGACACTGCACGAGCTGCTCA-3’ and reverse primer:

5'-CAGTTGGGTGGACATGGCAG-3’.

2.11 RNA immunoprecipitation

RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) with Ythdf1 antibody (Proteintech, cat. no. 17479-1-AP) was performed with EZ-Magna RIP™

2.12 RNA lifetime measurement

HCT116 cells were seeded in 6-well culture plates and treated with 5 mg/ml actinomycin D for 6 h and 3 h. RNA was isolated with Trizol® reagent and qRT-PCR was conducted. The degradation rate (k) and RNA lifetime (t1/2) were calculated as previously

2.13 Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA)

Serum was collected from colitis and CAC mouse models, and cytokine concentrations were detected using ELISA kits from Shanghai Hengyuan Biotechnology Inc. (Shanghai, China).

2.14 Lentivirus production and infection

Human Ythdf1 shRNA sequences were cloned into pLV3 and co-transfected into HEK293T using Lipofectamine®3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with packaging plasmids (pGag/Pol, pRev and pVSV-G) according to manufacturer’s protocol. The culture medium was collected 48 h following transfection and centrifuged to isolate the lentivirus particles. Stable shYTHDF1 HCT116 cells were generated following lentivirus infection and puromycin selection. The sequence of the shRNA oligo targeting YTHDF1 was

2.15 siRNA preparation and transfection

siRNA oligos were synthesized by GenePharma (Shanghai, China). RNase-free water was added to siRNA to prepare a 20 μM solution. siRNA was transiently transfected into cells with Lipofectamine®3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The siRNA sequences are listed in Table S1.

2.16 Histological analysis

Freshly-isolated colon and ileum tissues were cleaned and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (for HE and immunohistochemistry (IHC)) or Carnoy’s Fluid (for Alcian blue/periodic acid-Schiff (AB/PAS) staining; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Beijing, China). Then, the tissues were embedded in paraffin, cut into 5 µm-thick sections, dewaxed, hydrated and stained using standard HE or IHC procedures. An AB-PAS Stain kit (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co.) was used for goblet cell staining. Anti Ki67 (1:500; cat. no. ab15580), anti p-Stat3 (1:300; cat. no. Y705) (cat. no. ab6315), anti F4/80 (1:30; cat. no. ab16911), anti-Ly6g (1:50; cat. no. ab25377),

2.17 TUNEL assay

TUNEL assays were performed with the One Step TUNEL Apoptosis Assay kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology), according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

2.18 Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 7 software (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). The Kaplan–Meier method and log-rank test were used to analyse survival rates, and all other data were analysed using unpaired Student’s t tests. The data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. of three independent experiments. P < 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

3. Results

3.1 Ythdf1 protects mice from DSS-induced colitis

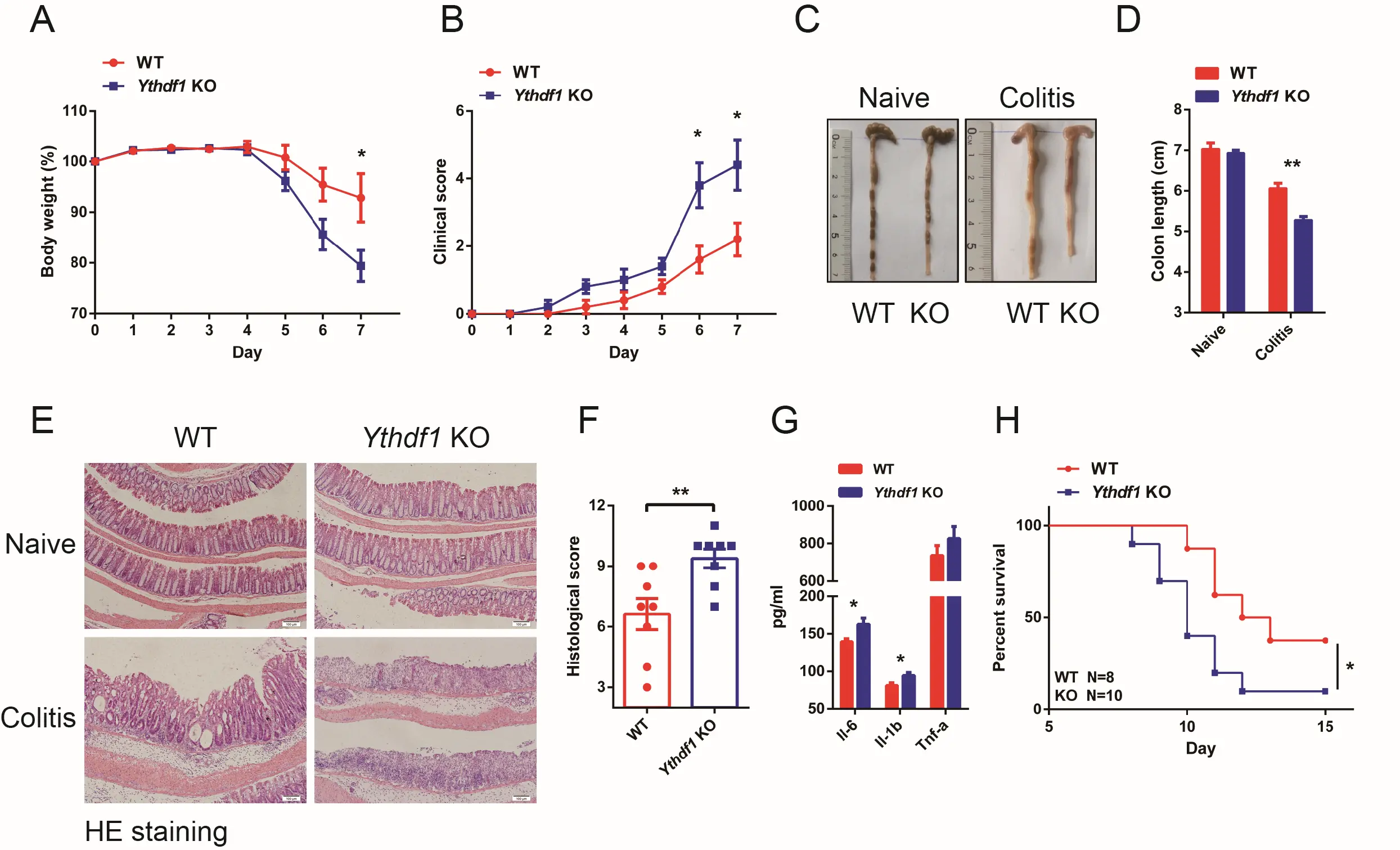

To examine the function of Ythdf1 in intestinal homeostasis, littermate wild-type (WT) and Ythdf1−/− mice were used and challenged with 2.5% DSS in their drinking water for five days, followed by normal water for two days. Following sacrifice on day 7, Ythdf1 deficiency was found to increase the severity of colitis compared with the WT control, as evidenced by a more marked and rapid drop in body weight, shortened colon length, and an increase in diarrhoea and bloody stools (Figure 1A,B,C,D; Figure S1). Histopathologically, Ythdf1−/− colons had a greater degree of leukocyte infiltration and mucosal damage, and a significantly increased histological score for colon inflammatory infiltration, crypt loss and ulceration compared with the control (Figure 1E,F). Moreover, significant increases in pro-inflammatory Il-6 and Il-1β expression were observed in the serum of Ythdf1−/− mice compared with WT mice (Figure 1G). When subjected to 4% DSS, Ythdf1−/− mice also experienced significantly reduced survival compared with WT mice

Figure 1. Ythdf1 deficiency exacerbates DSS-induced colitis. (A) Body weight and (B) and clinical scores of WT (n = 5) and KO (n = 5) mice following DSS treatment;

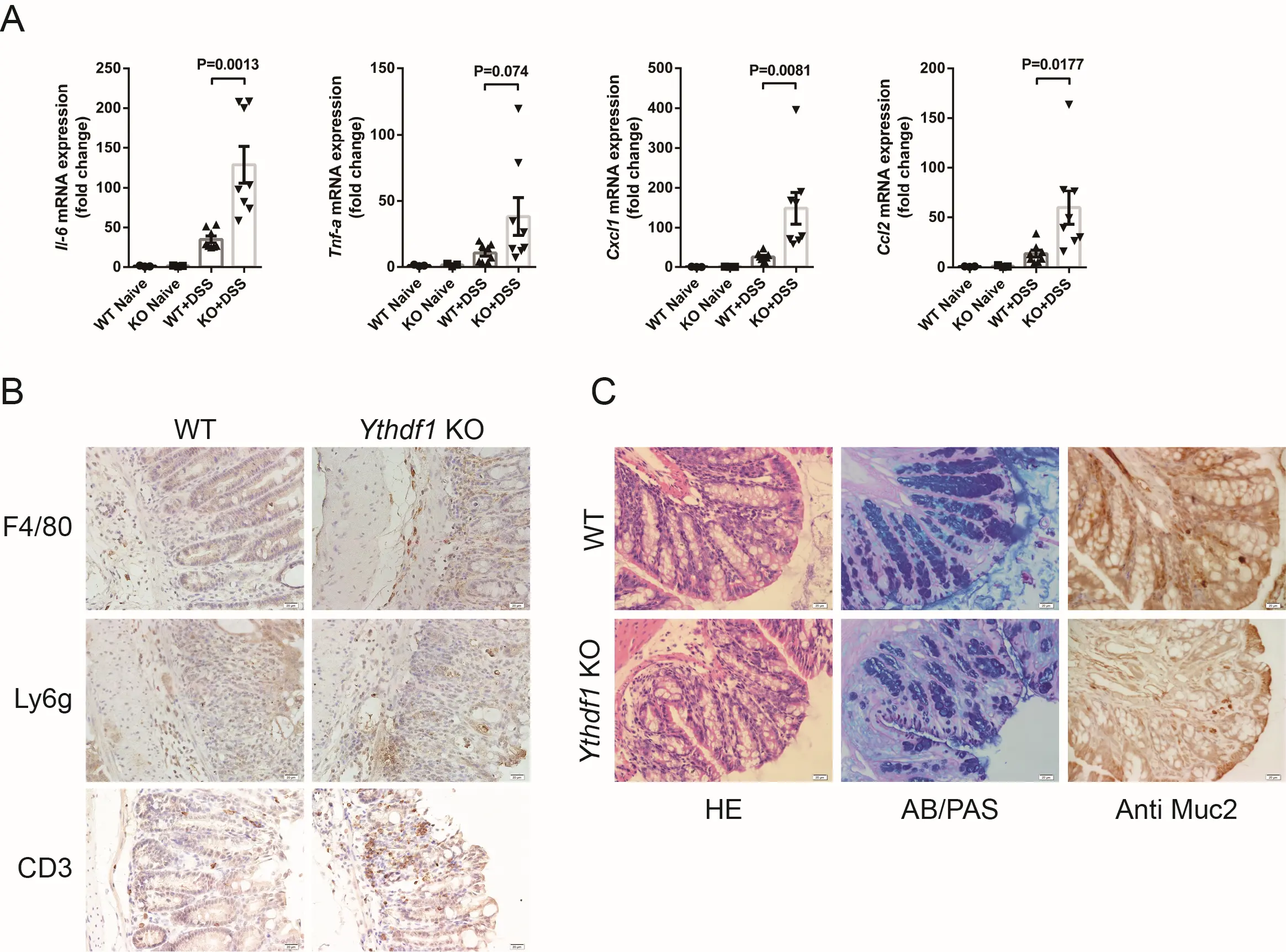

To obtain more evidence of local colon inflammation, quantitative real time-PCR was performed. Following exposure to DSS, proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine mRNA expression levels in distal colon tissues were significantly increased in Ythdf1−/− mice compared with WT mice (Figure 2A). The sole exception was Tnf-α, where the increase was only marked. IHC analysis of F4/80, Ly6g and CD3 expression also increased infiltration of macrophages, neutrophils, and T cells in Ythdf1−/− mice compared with WT mice (Figure 2B). Furthermore, similar frequencies of immune cells in the spleen and the mesenteric lymph nodes were detected in WT and Ythdf1−/− mice after colitis was induced, suggesting normal functions of peripheral lymphoid organs in Ythdf1−/− mice even under inflammatory conditions compared with WT (Figure S2A).

Figure 2. Loss of Ythdf1 exacerbates DSS-induced intestinal inflammation. (A) qRT-PCR analysis of Il-6, Tnf-α, Cxcl1 and Ccl2 mRNA expression in distal colon tissues before

As a representative type of secretory cells, goblet cell depletion is a clinical feature of human ulcerative colitis[29,30]. To determine whether goblet cell dysfunction is a cause of colitis or a secondary effect of increased inflammation in our mouse models, we examined colon sections from day 4 of DSS treatment. At this stage, colitis clinical symptoms are typically absent[31]. There was already a marked reduction in goblet cells at day 4, accompanied by an increased number of immature goblet cells in Ythdf1 KO colon tissues (Figure 2C; left and middle). Mucin2 is primarily secreted by goblet cells[32], and the reduction of goblet cells observed in our models was accompanied by decreased Mucin2 secretion (Figure 2C; right). Antimicrobial peptide-producing Paneth cells are another important secretory cell type, which exist in the ileum but not the colon, and are required for appropriate antibacterial reactions and intestinal homeostasis. We did not observe defects in Paneth cell function during colitis development, as evidenced by IHC analysis of lysozyme expression (Figure 1B). This indicated that the loss of Ythdf1 had no effect on Paneth cell function under normal or inflammatory conditions. Together, these data confirm that Ythdf1 deficiency exacerbates colonic inflammation, mucosal damage, and goblet cell loss, thereby promoting the development of colitis.

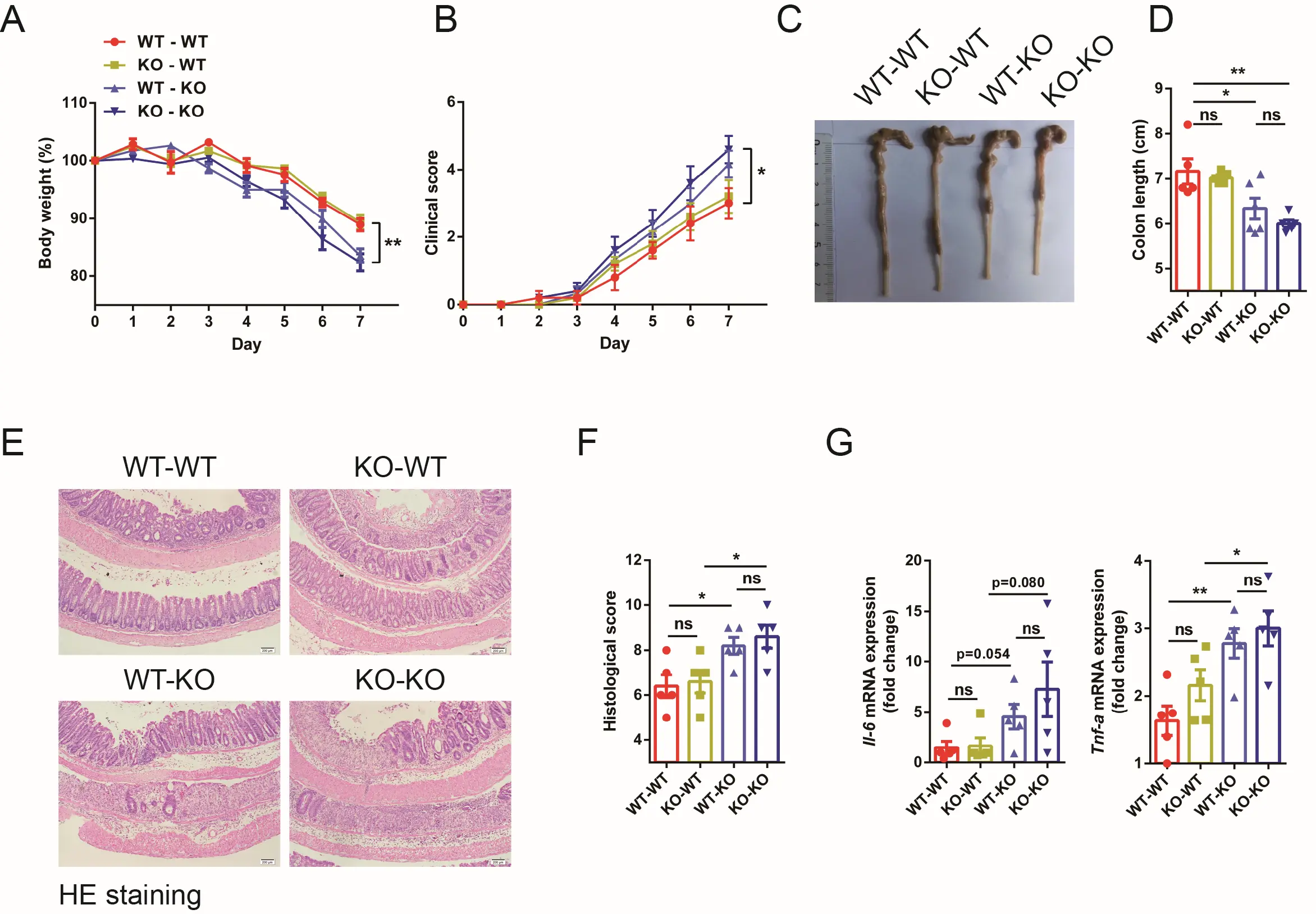

3.2 Ythdf1 deficiency-exacerbated colitis is prominently linked to intrinsic changes

Colonic inflammation and the development of colitis could be attributable to the exacerbated hematopoietic environment. To investigate this possibility, a bone marrow transplantation assay was conducted. X-ray irradiated WT and Ythdf1−/− mice were reconstituted with bone marrow cells from either WT or Ythdf1−/− mice. Four chimeric mice groups resulted: WT-WT, KO-WT, WT-KO and KO-KO, and reconstitution was confirmed to be successful (Figure S3). These mice were then challenged with DSS to induce colitis. Colitis was not significantly alleviated in Ythdf1−/− mice receiving bone marrow cells from WT donors (WT-KO) compared with those receiving Ythdf1−/− ones (KO-KO), as evidenced by body weight change, colon length reduction, diarrhoea and the presence of blood in their stools (Figure 3A,B,C,D). Similarly, colitis status was not significantly exacerbated in WT mice receiving Ythdf1−/− bone marrow cells (KO-WT) compared with those receiving WT cells (WT-WT; Figure 3C,D). Histological analysis of colon sections revealed increased infiltration of leukocytes, mucosal damage and crypt loss in Ythdf1−/− recipients, regardless of the origins of their donor cells (Figure 3E,F). Furthermore, elevated Il-6 and Tnf-α mRNA levels in distal colon tissues after DSS treatment were detected, but these were hardly affected by bone marrow transplantation (Figure 3G). These data suggest that Ythdf1 deficiency aggravates

Figure 3. Ythdf1−/−-promoted colitis is marginally linked to hematopoietic cells. (A) Body weight and (B) clinical colitis score of bone marrow-reconstituted mice following DSS treatment (n = 5 for each group); (C) Representative colon images and (D) colon lengths from the bone marrow-reconstituted mice; (E) Representative images of HE-stained colon sections (scale bar, 100 μm) and (F) histological scores; (G) qRT-PCR analysis of Il-6 and Tnf-α expression in distal colon tissues after colitis. Data are presented as the means ± s.e.m; *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01. DSS: dextran sodium sulfate; WT: wild type; KO: Ythdf1 knockout mice; BMCs: bone marrow cells; WT-WT: WT recipient mice reconstituted with WT BMCs; KO-WT: WT mice reconstituted with Ythdf1 KO BMCs; WT-KO: Ythdf1 KO mice reconstituted with WT BMCs; KO-KO: Ythdf1 KO mice reconstituted with Ythdf1 KO BMCs.

3.3 Ythdf1 buffers the activation of Il6-Jak1-Stat3 pathway

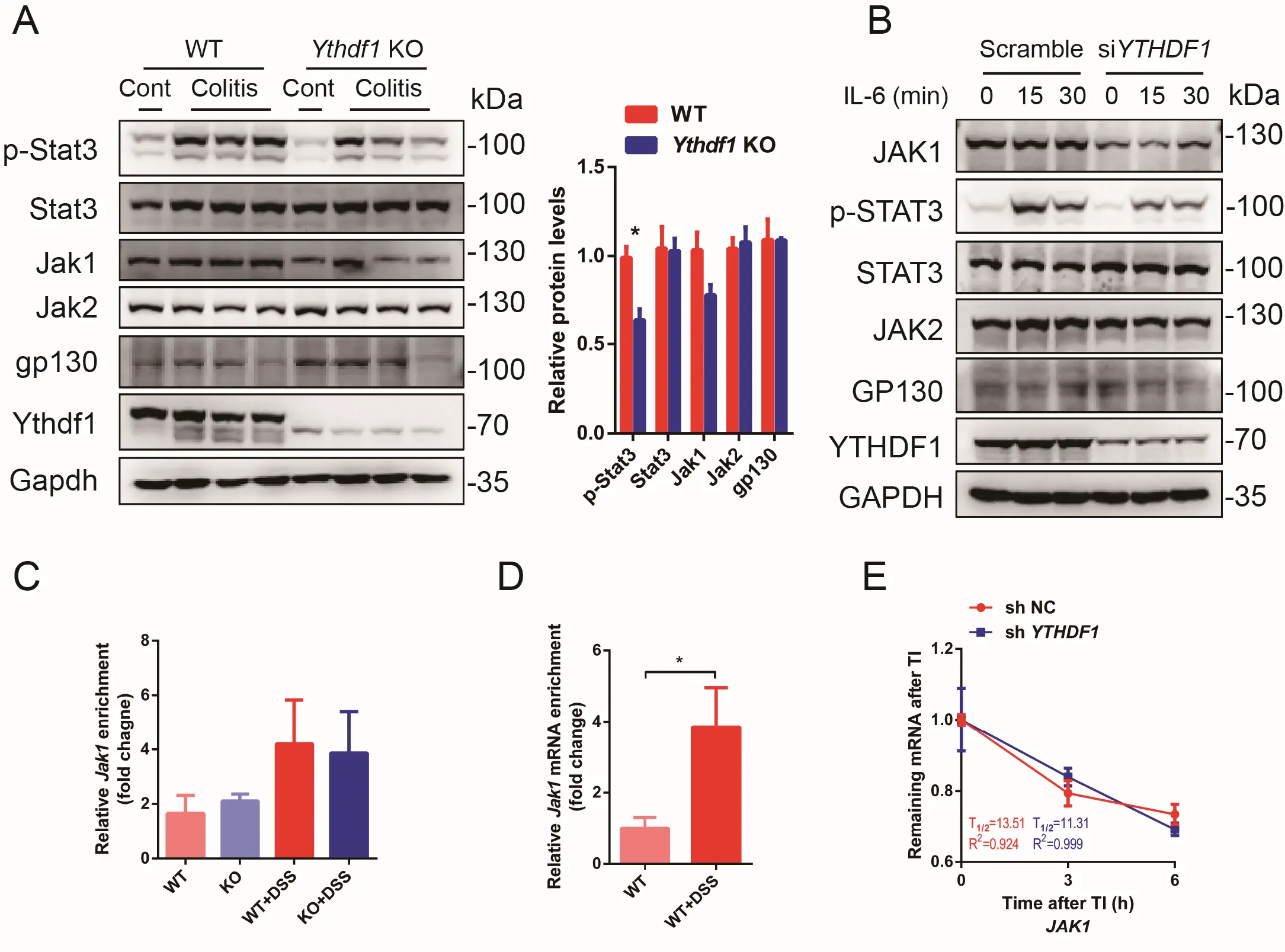

To delineate the molecular mechanisms underlying colon epithelial inflammation and regeneration in Ythdf1−/− colitis, signalling pathways of NF-κB, MAPKs (Jnk, Erk and P38) and Stat3 were examined. Interestingly, a significant decrease in P-Stat3 levels in

Jak1 is an essential kinase of Stat3 that controls proliferation and (auto)inflammation during pathogenesis of IBD[33,34]. In colon cancer cells (HCT116) and bone marrow-derived macrophages, METTL3-mediated Jak1 m6A modification has been reported to promote its translation and thereby strengthen Stat3 signalling through Ythdf1[35,36]. Intriguingly, while the total mRNA level of Jak1 decreased upon DSS treatment (Figure S4B), the protein level was hardly affected (Figure 4A). By contrast, while loss of Ythdf1 merely affected the mRNA level of Jak1, its protein level was decreased (Figure 4A). Notably, neither mRNA nor protein levels of Jak2 and gp130 were changed upon Ythdf1 KO or knockdown (KD) (Figure 4A,B and Figure S4C). MeRIP revealed m6A modification of Jak1 in WT and

Figure 4. Jak1 is m6A modified and a target of Ythdf1. (A) Western blot analysis and quantification of key proteins related with Jak1-Stat3 pathway in colon epithelial cells collected from control and DSS-induced colitis mouse models. One lane represents one sample from an individual mouse; (B) Western blot analysis of STAT3 (p-Y705), JAK1, JAK2 and GP130 levels in HCT116 cells treated with Scramble or siYTHDF1 siRNA and stimulated with IL-6 at indicated time points; (C) Methylated RNA immunoprecipitation (MeRIP)-qPCR analysis of m6A-modified (m6Aed) Jak1 mRNA level before and after DSS treatment in WT and Ythdf1 KO colon epithelial cells (n = 2 for WT,KO and WT+DSS;

IL-6 is a key member of IL-6 cytokine family, which is upregulated during colitis and serves as a potent Jak1-Stat3 pathway activator in colon epithelial cells[20,21,37]. To confirm the involvement of Il-6-Jak1-Stat3 signalling in Ythdf1 deficiency-induced colitis, HCT116 cells were treated with siYTHDF1-siRNA and stimulated with IL-6. As shown, YTHDF1 KD significantly decreased the expression level of JAK1 while rarely influencing that of JAK2 or GP130 (Figure 4B). A significant decrease in p-STAT3 level was found in

3.4 Ythdf1 ensures epithelial cell survival upon DSS treatment

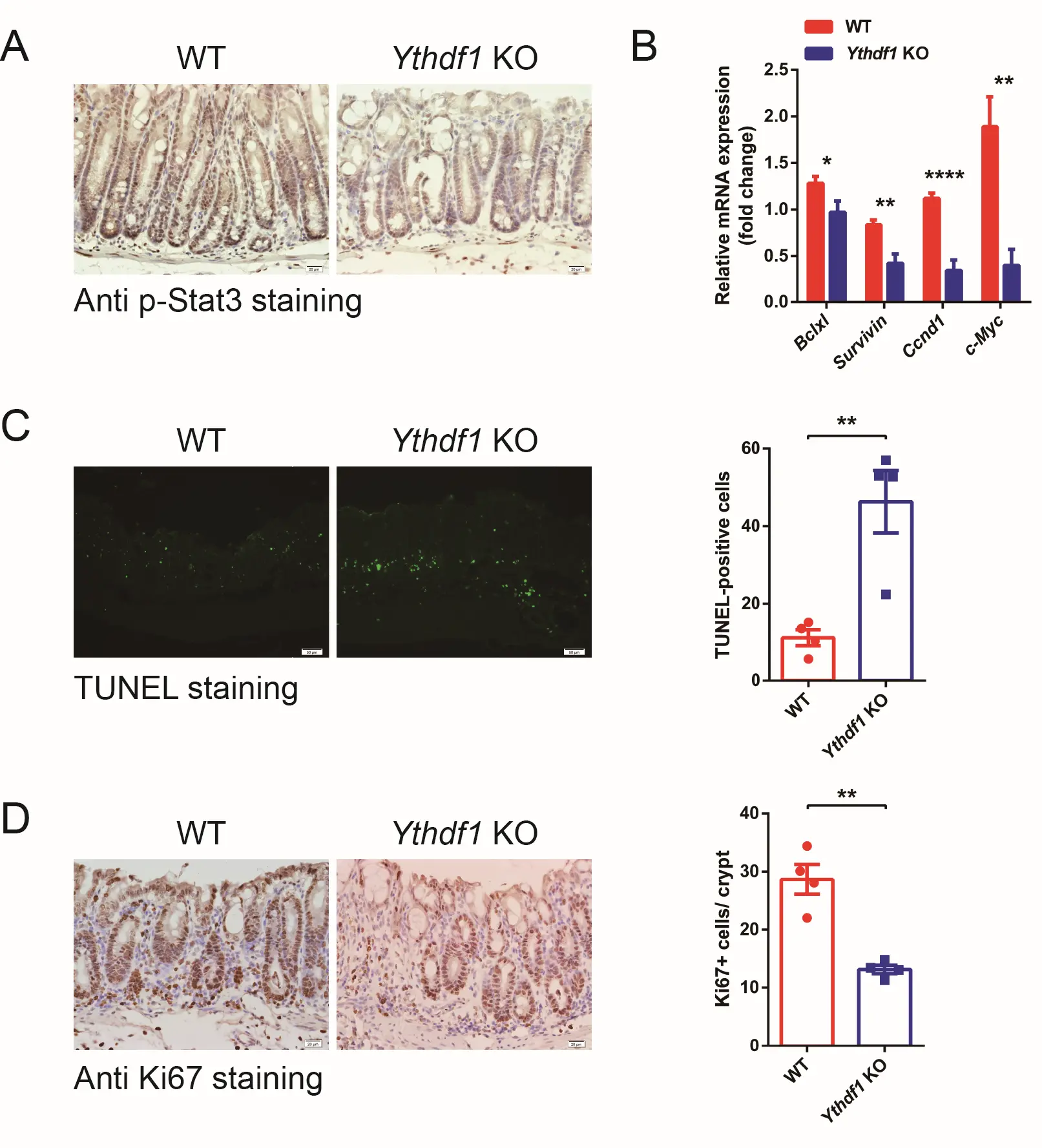

The Il6-Jak1-Stat3 pathway is pivotal in cell proliferation and survival[22,38]. We confirmed that the p-Stat3 level was decreased in Ythdf1 KO colitis sections compared with WT sections (Figure 5A). In addition, qRT-PCR analysis revealed that Stat3 downstream target genes, including Bclxl, Survivin, Ccnd1 and c-Myc, were all significantly downregulated (Figure 5B). Further TUNEL staining revealed that apoptosis was significantly enhanced in Ythdf1−/− colitis colon tissues compared with the WT (Figure 5C). This was accompanied by reduced cell proliferation, as determined by anti-Ki67 staining (Figure 5D). Notably, the apoptosis and cell proliferation levels were comparable between WT and Ythdf1−/− colon under normal conditions (Figure S5). Thus, Ythdf1 safeguards epithelial cell survival in response to environmental stress.

Figure 5. Loss of Ythdf1 compromises Stat3 activation and colon epithelial cell survival. (A) Representative images of anti p-Stat3 expression in colon sections from WT and KO mice following the induction of colitis, as assessed by IHC (scale bar, 20 μm); (B) qRT-PCR analysis of Stat3 target gene expression in colon tissue from DSS-challenged WT (n = 8) and KO mice (n = 7); (C) TUNEL analysis of apoptotic cells, with quantification, in WT and KO mice following the induction of colitis (scale bar, 50 μm); (D) IHC analysis of Ki-67 expression and quantification in WT and KO mice following the induction of colitis. Data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ****P < 0.0001. DSS: dextran sodium sulfate; WT: wild type; KO: Ythdf1 knockout mice; IHC: immunohistochemistry.

3.5 Ythdf1 promotes malignancy transition in CAC model

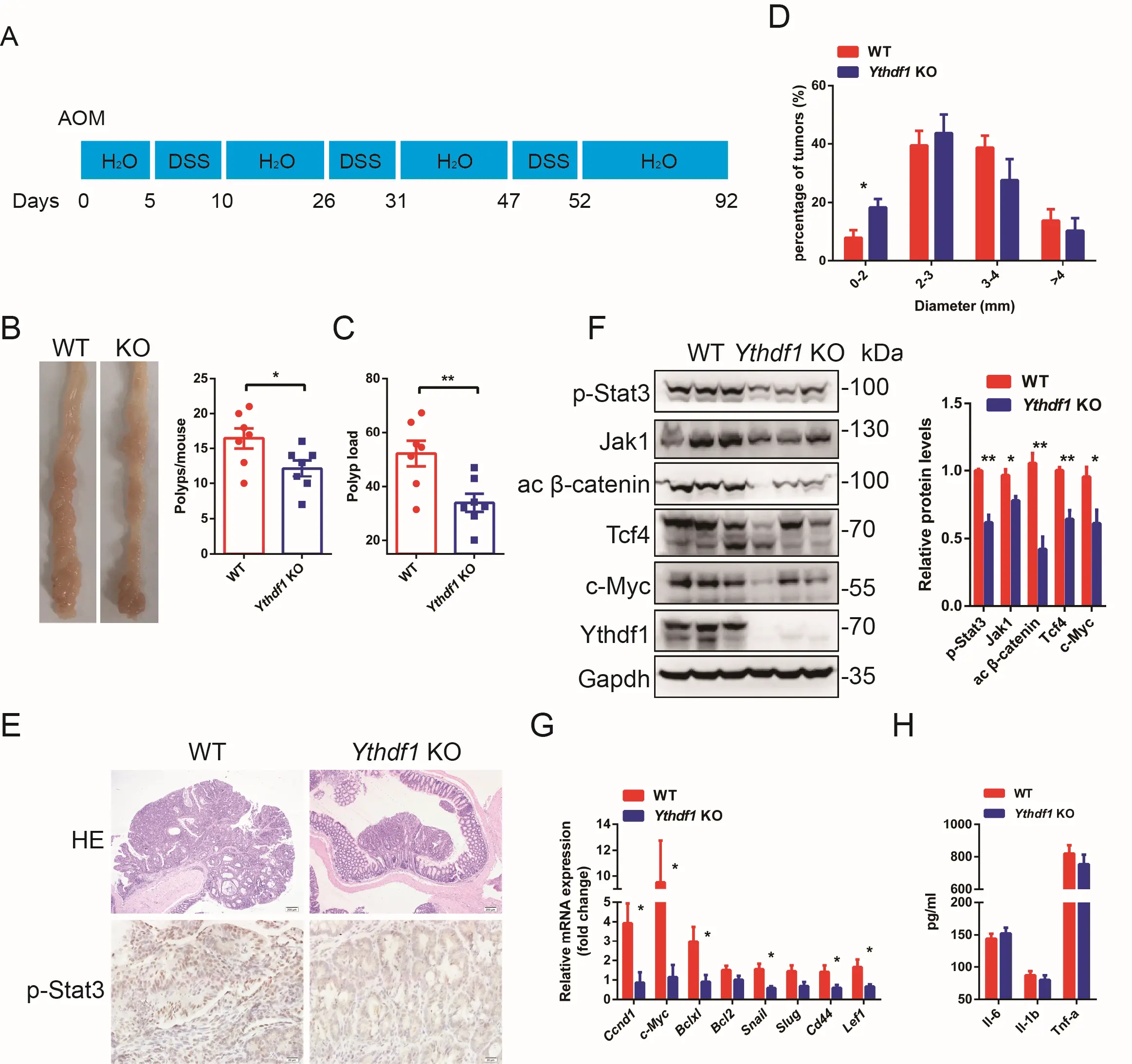

The above data showed that loss of Ythdf1 compromised the activation of the Il6-Jak1-Stat3 pathway, which ensures post-damage survival of colon epithelial cells, thereby causing colitis. Inflammation- and/or hyperproliferation-promoted malignant transition has been the subject of extensive studies[39]. In the present study, we generated an AOM/DSS-induced CAC mouse model to investigate the involvement of Ythdf1 in colitis (inflammation)-induced malignant transition (Figure 6A). Interestingly, Ythdf1−/− mice developed significantly fewer polyps compared with the WT, and polyp load was markedly decreased in these mice (Figure 6B,C). In addition, Ythdf1−/− tumours were smaller than those from WT mice (Figure 6D). Adenomas with high-grade dysplasia were more frequent in WT than in Ythdf1−/− mice (Figure 6E). Both IHC and western blot analysis revealed decreased p-Stat3 expression in tumour tissues from Ythdf1−/− mice compared with WT mice, accompanied by downregulated Jak1 expression (Figure 6E,F). Of note, the activated

Figure 6. Ythdf1 promotes malignant transformation in a mouse CAC model. (A) A schematic of the induction procedure of the model by AOM/DSS. All mice were sacrificed for analysis at day 92; (B) Representative colon images (left) and polyp numbers (right) of WT and KO CAC mouse models (n = 7). (C) Polyp load in WT and Ythdf1 KO mice following the induction of CAC; (D) Size distribution of colon tumours in WT and KO mice; (E) Representative images of HE-stained colon tumours (upper; scale bar, 200 μm) and IHC stained p-Stat3 expression in WT and KO mice; (F) Western blot analysis and quantification of p-Stat3 (Y705), Jak1, activated β-catenin, Tcf4 and c-Myc expression in colon samples collected from WT and KO mice following the induction of CAC. One lane represents one sample from an individual mouse; (G) qRT-PCR analysis of Stat3 and

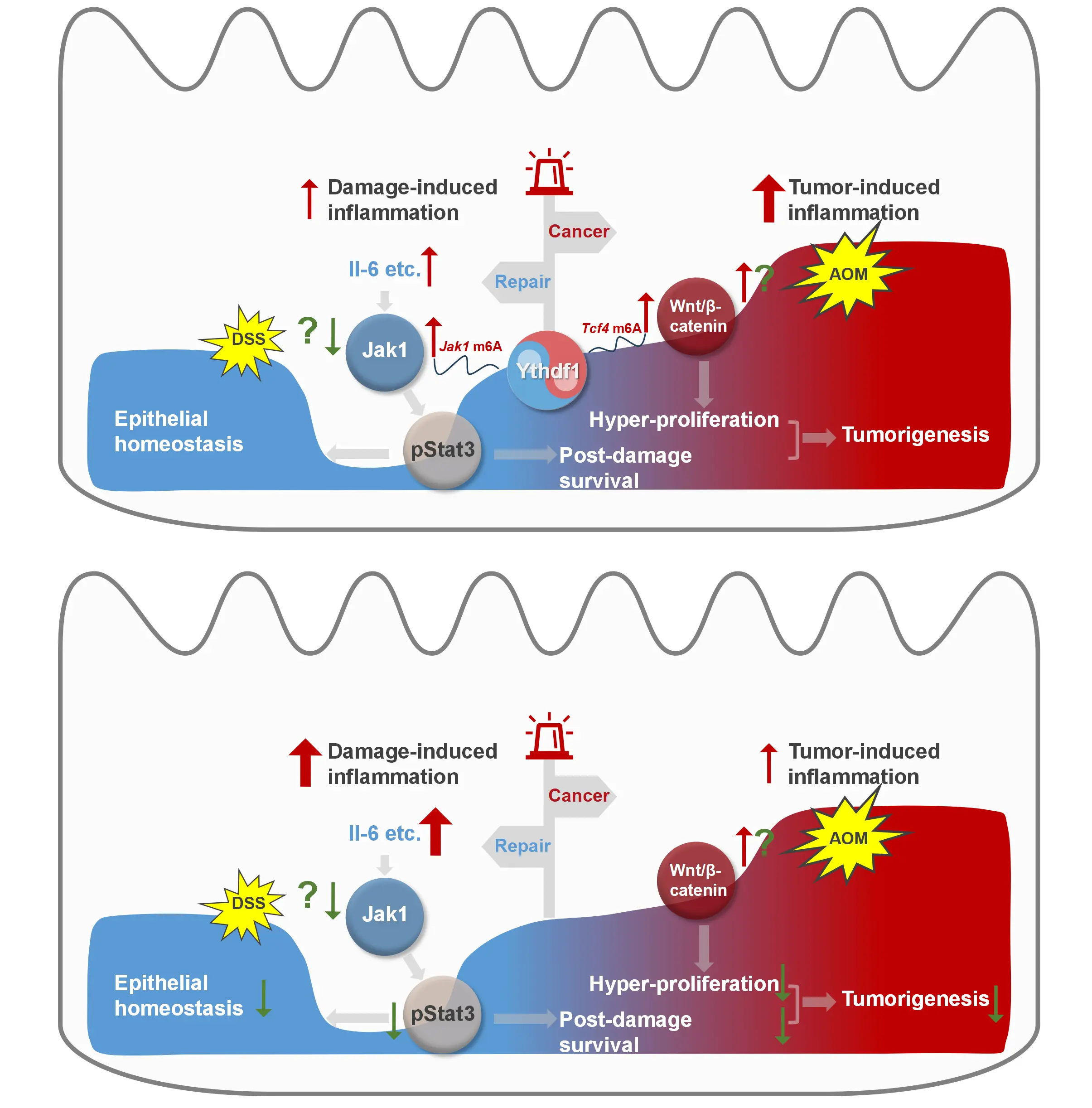

Putting together, we summarized the findings in a schematic model (Figure 7). In response to epithelial damage caused by DSS, the transcription of Jak1 is initially suppressed, which fails to activate Stat3 (p-Stat3) and likely mediates apoptotic clearance of the damaged colon epithelium. As an adaptive response, the Jak1 mRNA is rapidly m6A-modified and, in cooperation with Ythdf1, more efficiently translated into protein to a comparable level to the naïve stage. If Wnt/β-catenin signalling is aberrantly activated in

Figure 7. A schematic overview of Ythdf1-centred interplay between colitis and colon cancer.

4. Discussion

In the present study, we showed that a m6A-modified RNA binding protein, Ythdf1, protects mice from the DSS-induced colitis. Ythdf1 is involved in the function of goblet cells, which secrete mucus and provide the first line of defence for the gastrointestinal tract. At the molecular level, though DSS treatment suppresses the transcription of Jak1, its protein level is compensated by Ythdf1-enhanced translation, ensuring colon epithelial repair. Loss of Ythdf1 compromises the activation of Il-6-Jak1-Stat3 signalling and hence the post-damage survival of colon epithelial cells. Intriguingly, the loss of Ythdf1 rather protects the mice from AOM/DSS-induced colon cancer.

The Il6-Jak1-Stat3 pathway is pivotal in cell proliferation, stemness maintenance, and post-damage survival, the dysregulation of which is linked to autoimmune disease and colon cancer[22,38]. Here, we revealed a buffer function of Ythdf1 in the regulation of

Loss of Ythdf1 exacerbates colitis/inflammation but inhibits colon tumour propagation in the AOM/DSS-induced CAC model. The activation of Stat3 and the expression of its downstream genes were decreased in both Ythdf1-deficient colitis and colon tumours. Of note, while Wnt/β-catenin signalling was barely changed in WT and Ythdf1−/− colon epithelium before and after colitis development, it was attenuated upon Ythdf1 deletion in the CAC model. This is consistent with the report by Han et al., which showed that the intestinal-specific Ythdf1 deletion prevents the progression of colorectal cancer in Apcmin/+ mice and the AOM/DSS-induced CAC model, attributable to attenuated Wnt/β-catenin signalling[18]. Han’s findings and ours together suggest that the Ythdf1-buffered activation of Jak1-Stat3 signalling acts alone to ensure epithelial repair during colitis, but later on, it is hijacked by activated

The buffer function of Ythdf1 supports the notion that RNA-binding proteins represent an additional layer of control over gene expression, and in intestinal homeostasis, help IECs to rapidly and accurately respond to external stimuli. The intestinal-specific deletion of human antigen R (HuR) has been found to reduce tumour burden in both Apcmin/+ and AOM/DSS mouse models, but this also exacerbates doxorubicin-induced intestinal injury[40]. IEC-specific deletion of IMP1 (IGF2BP1) promotes epithelial regeneration and thus prevents DSS-induced colitis[41], but augments LIN28B-induced oncogenic effects in the intestine; LIN28B is an RNA-binding protein[42]. IMP1 is an m6A reader[43]; however, whether its epithelial repair functions are m6A-modification dependent remains to be determined.

Several limitations of the present study should be acknowledged. First, although bone marrow transplantation experiments strongly suggest that the observed phenotypes are predominantly driven by non-hematopoietic compartments, we relied on a global Ythdf1 knockout model rather than an intestinal epithelial cell–specific deletion. Therefore, we cannot formally exclude potential

Supplementary materials

The supplementary material for this article is available at: Supplementary materials.

Acknowledgements

Authors are grateful to Dr. Jessica Tamanini (Shenzhen University and ETediting) for editing the manuscript prior to submission.

Authors contribution

Zhang Z: Conceptualization, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, writing-original draft.

Zhang J: Conceptualization, methodology, data curation, formal analysis.

Xu C, Ning Y: Data curation, formal analysis.

Liu B: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, funding acquisition, writing-original draft.

Conflicts of interest

Baohua Liu is the Editor-in-Chief of Ageing and Cancer Research & Treatment. The other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Animal experiments were handled in accordance with ethical and scientific standards approved by the Committee on the Use of Live Animals in Teaching and Research, Shenzhen University, China (Protocol No. 2020001).

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The data and materials could be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 32430048, 82125012 and 82488301 to Baohua Liu), the Shenzhen Medical Research Fund (C2406001), the National Key R&D Program of China STI2030-Major Projects (2021ZD0202400 to Baohua Liu), the Shenzhen Municipal Commission of Science and Technology Innovation (JCYJ20220818100016035 and JCYJ20220818100009020 to Baohua Liu).

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

References

-

1. Rudbaek JJ, Agrawal M, Torres J, Mehandru S, Colombel JF, Jess T. Deciphering the different phases of preclinical inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;21(2):86-100.[DOI]

-

2. Kaplan GG. The global burden of inflammatory bowel disease: From 2025 to 2045. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025;22(10):708-720.[DOI]

-

3. Fanizza J, Bencardino S, Allocca M, Furfaro F, Zilli A, Parigi TL, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer. Cancers. 2024;16(17):2943.[DOI]

-

4. Selvakumar B, Samsudin R. Intestinal barrier dysfunction in inflammatory bowel disease: Pathophysiology to precision therapeutics. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2025;31(12):3450-3464.[DOI]

-

5. Beumer J, Clevers H. Cell fate specification and differentiation in the adult mammalian intestine. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021;22(1):39-53.[DOI]

-

6. Das S, Parigi SM, Luo X, Fransson J, Kern BC, Okhovat A, et al. Liver X receptor unlinks intestinal regeneration and tumorigenesis. Nature. 2025;637(8048):1198-1206.[DOI]

-

7. He PC, He C. m6A RNA methylation: from mechanisms to therapeutic potential. EMBO J. 2021;40(3):EMBJ2020105977.[DOI]

-

8. Zaccara S, Jaffrey SR. Understanding the redundant functions of the m6A-binding YTHDF proteins. RNA. 2024;30:468-481.[DOI]

-

9. Shi H, Wei J, He C. Where, when, and how: Context-dependent functions of RNA methylation writers, readers, and erasers. Mol Cell. 2019;74(4):640-650.[DOI]

-

10. Flamand MN, Tegowski M, Meyer KD. The proteins of mRNA modification: Writers, readers, and erasers. Annu Rev Biochem. 2023;92:145-173.[DOI]

-

11. Wang X, Zhao BS, Roundtree IA, Lu Z, Han D, Ma H, et al. N6-methyladenosine modulates messenger RNA translation efficiency. Cell. 2015;161(6):1388-1399.[DOI]

-

12. Shi H, Zhang X, Weng YL, Lu Z, Liu Y, Lu Z, et al. m6A facilitates hippocampus-dependent learning and memory through YTHDF1. Nature. 2018;563(7730):249-253.[DOI]

-

13. Liu T, Wei Q, Jin J, Luo Q, Liu Y, Yang Y, et al. The m6A reader YTHDF1 promotes ovarian cancer progression via augmenting EIF3C translation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48(7):3816-3831.[DOI]

-

14. Yu H, Shi J, He R, Zhang X, Ren S, Chen Q, et al. Energy status orchestrates YTHDF1 phase separation and tumorigenesis. Cell Rep. 2025;44(11):116466.[DOI]

-

15. Han D, Liu J, Chen C, Dong L, Liu Y, Chang R, et al. Anti-tumour immunity controlled through mRNA m(6)A methylation and YTHDF1 in dendritic cells. Nature. 2019;566(7743):270-274.[DOI]

-

16. Bao Y, Zhai J, Chen H, Wong CC, Liang C, Ding Y, et al. Targeting m6A reader YTHDF1 augments antitumour immunity and boosts anti-PD-1 efficacy in colorectal cancer. Gut. 2023;72(8):1497-1509.[DOI]

-

17. Xu C, Yu C, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Zhang J, Meng Y, et al. YTHDF1 differentiates the contributing roles of mTORC1 in aging. Mol Cell. 2025;85(11):2194-2210.[DOI]

-

18. Han B, Yan S, Wei S, Xiang J, Liu K, Chen Z, et al. YTHDF1-mediated translation amplifies Wnt-driven intestinal stemness. EMBO Rep. 2020;21(4):EMBR201949229.[DOI]

-

19. Greten FR, Eckmann L, Greten TF, Park JM, Li ZW, Egan LJ, et al. IKKβ links inflammation and tumorigenesis in a mouse model of colitis-associated cancer. Cell. 2004;118(3):285-296.[DOI]

-

20. Grivennikov S, Karin E, Terzic J, Mucida D, Yu GY, Vallabhapurapu S, et al. IL-6 and Stat3 are required for survival of intestinal epithelial cells and development of colitis-associated cancer. Cancer Cell. 2009;15(2):103-113.[DOI]

-

21. Bollrath J, Phesse TJ, von Burstin VA, Putoczki T, Bennecke M, Bateman T, et al. gp130-mediated Stat3 activation in enterocytes regulates cell survival and cell-cycle progression during colitis-associated tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2009;15(2):91-102.[DOI]

-

22. Yu H, Pardoll D, Jove R. STATs in cancer inflammation and immunity: a leading role for STAT3. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9(11):798-809.[DOI]

-

23. Gobert AP, Latour YL, Asim M, Barry DP, Allaman MM, Finley JL, et al. Protective role of spermidine in colitis and colon carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(3):813-827.[DOI]

-

24. Maxwell JR, Brown WA, Smith CL, Byrne FR, Viney JL. Methods of inducing inflammatory bowel disease in mice. Curr Protoc Pharmacol Chapter. 2009;47(1):5-58.[DOI]

-

25. Xu J, Zhou L, Ji L, Chen F, Fortmann K, Zhang K, et al. The REGgamma-proteasome forms a regulatory circuit with IkappaBvarepsilon and NFkappaB in experimental colitis. Nat Commun. 2016;7(1):10761.[DOI]

-

26. Thaker AI, Shaker A, Rao MS, Ciorba MA. Modeling colitis-associated cancer with azoxymethane (AOM) and dextran sulfate sodium (DSS). J Vis Exp. 2012;67:e4100.[DOI]

-

27. Dominissini D, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Salmon-Divon M, Amariglio N, Rechavi G. Transcriptome-wide mapping of N6-methyladenosine by m6A-seq based on immunocapturing and massively parallel sequencing. Nat Protoc. 2013;8(1):176-189.[DOI]

-

28. Liu J, Eckert MA, Harada BT, Liu SM, Lu Z, Yu K, et al. m6A mRNA methylation regulates AKT activity to promote the proliferation and tumorigenicity of endometrial cancer. Nat Cell Biol. 2018;20(9):1074-1083.[DOI]

-

29. McCormick DA, Horton LW, Mee AS. Mucin depletion in inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Pathol. 1990;43(2):143-146.[DOI]

-

30. Strugala V, Dettmar PW, Pearson JP. Thickness and continuity of the adherent colonic mucus barrier in active and quiescent ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62(5):762-769.[DOI]

-

31. Nowarski R, Jackson R, Gagliani N, de Zoete Marcel R, Palm Noah W, Bailis W, et al. Epithelial IL-18 equilibrium controls barrier function in colitis. Cell. 2015;163(6):1444-1456.[DOI]

-

32. Gustafsson JK, Johansson MEV. The role of goblet cells and mucus in intestinal homeostasis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;19(12):785-803.[DOI]

-

33. Danese S, Argollo M, Le Berre C, Peyrin-Biroulet L. JAK selectivity for inflammatory bowel disease treatment: Does it clinically matter? Gut. 2019;68(10):1893-1899.[DOI]

-

34. Agashe RP, Lippman SM, Kurzrock R. JAK: Not just another kinase. Mol Cancer Ther. 2022;21(12):1757-1764.[DOI]

-

35. Xiong J, He J, Zhu J, Pan J, Liao W, Ye H, et al. Lactylation-driven METTL3-mediated RNA m6A modification promotes immunosuppression of tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells. Mol Cell. 2022;82(9):1660-1677.[DOI]

-

36. Sun Y, Gong W, Zhang S. METTL3 promotes colorectal cancer progression through activating JAK1/STAT3 signaling pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2023;14(11):765.[DOI]

-

37. Liu X, Wei W, Li X, Shen P, Ju D, Wang Z, et al. BMI1 and MEL18 promote colitis-associated cancer in mice via REG3B and STAT3. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(6):1607-1620.[DOI]

-

38. Xue C, Yao Q, Gu X, Shi Q, Yuan X, Chu Q, et al. Evolving cognition of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway: autoimmune disorders and cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):204.[DOI]

-

39. Wen Y, Zhu Y, Zhang C, Yang X, Gao Y, Li M, et al. Chronic inflammation, cancer development and immunotherapy. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:1040163.[DOI]

-

40. Giammanco A, Blanc V, Montenegro G, Klos C, Xie Y, Kennedy S, et al. Intestinal epithelial HuR modulates distinct pathways of proliferation and apoptosis and attenuates small intestinal and colonic tumor development. Cancer Res. 2014;74(18):5322-5335.[DOI]

-

41. Chatterji P, Williams PA, Whelan KA, Samper FC, Andres SF, Simon LA, et al. Posttranscriptional regulation of colonic epithelial repair by RNA binding protein IMP1/IGF2BP1. EMBO Rep. 2019;20(6):EMBR201847074.[DOI]

-

42. Chatterji P, Hamilton KE, Liang S, Andres SF, Wijeratne HS, Mizuno R, et al. The LIN28B-IMP1 post-transcriptional regulon has opposing effects on oncogenic signaling in the intestine. Genes Dev. 2018;32:1020-1034.[DOI]

-

43. Huang H, Weng H, Sun W, Qin X, Shi H, Wu H, et al. Recognition of RNA N6-methyladenosine by IGF2BP proteins enhances mRNA stability and translation. Nat Cell Biol. 2018;20(3):285-295.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite