Abstract

The family of Nectin and Nectin-like molecules (Necls) and their immunoreceptors are essential in the immune response against cancer. While primarily involved in cell adhesion, motility, and proliferation, some Nectin members also serve as ligands for both stimulatory and inhibitory immune receptors, influencing immune responses. The Nectin/Necls and their receptors form a complex regulatory axis crucial for natural killer (NK) and T cell activity. The most relevant ligands in this axis are the Nectin CD112 and the Nectin-like molecule CD155. Both are ligands for the activating receptor DNAX accessory molecule-1 (DNAM-1) and the inhibitory receptor T cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains (TIGIT). Additionally, CD155 is a ligand for T cell activation induced late expression (TACTILE), and CD112 for poliovirus receptor related immunoglobulin domain containing (PVRIG), both inhibitory receptors. These ligands bind with higher affinity to their inhibitory receptors than to the activating receptor DNAM-1. Recent advances in cancer immunotherapy have focused on identifying new targets to overcome tumor resistance. Antibody-mediated blockade of inhibitory receptors such as TIGIT, TACTILE, and PVRIG on NK and T cells has shown promising results in animal models and clinical trials, helping to break immune tolerance. Aging significantly increases cancer risk and contributes to the deterioration of the immune response, impairing cancer immune surveillance. Aging is also associated with an altered tumor microenvironment, reducing immune cell infiltration and promoting tumor progression. In elderly cancer patients, both immunosenescence and cancer-related immunosuppression contribute to a defective immune response against tumor cells. Thus, cancer immunotherapy strategies should be personalized to overcome the dysfunctional immune responses in elderly cancer patients. Understanding these interactions, including ligand-receptor binding mechanisms, is vital for developing effective immunotherapies. Since cancer predominantly affects older adults, further research is needed to explore how aging impacts Nectin-receptor interactions and to tailor immunotherapy strategies for elderly patients.

Keywords

1. Introduction

The Nectin family of adhesion proteins and their immunoreceptors play a pivotal role in the immune response against cancer. The molecules of the Nectin family can regulate cell adhesion, motility and proliferation, and, in addition, some members are ligands of both costimulatory and inhibitory immune receptors and modulate immune responses[1]. The progress made in the search and development of new immunotherapeutic strategies has focused over the last decade on the identification of novel targets as immune checkpoints to reverse cancer resistance to immune cells. Thus, antibody-mediated blockade of inhibitory checkpoint receptors expressed on Natural killer (NK) cells and T cells has demonstrated to break tolerance to cancer in animal models and some clinical settings[2]. The tumor microenvironment (TME) is a complex and heterogeneous ecosystem where cancer cells interact with host cells (e.g. fibroblasts, immune cells, endothelial cells), influencing tumor growth. Thus, a supportive TME fosters cancer, while an immunosuppressive one allows immune escape. These facts highlight the role of the TME as a crucial target for novel cancer therapies[3]. The study of the aging TME is emerging as a key focus in cancer research, and a better knowledge of how TME is influenced by age and contributes to creating a pro-tumorigenic niche is required for the development of age-specific cancer therapies.

Immunosenescence refers to the changes in the immune system associated with aging, leading to dysfunctional immune responses. In the elderly, the immune response is altered, with a decreased ability to fight new infections and reduced immunosurveillance against cancer. Age is generally considered the most significant risk factor for most cancers, with incidence rates rising steadily as people get older because of accumulated cellular mutations, increased inflammation (inflamm-aging), and prolonged exposure to environmental factors[4,5].

In this review, we focus on the interaction of Nectin and Nectin-like molecules with their receptors on immune cells and how these interactions contribute to immunosurveillance or immune evasion in cancer. Cancer is a disease that primarily affects older adults, and the aging of the tumor microenvironment may influence its progression. Further studies are needed to analyze how age modifies the interactions of Nectins with their immunoreceptors to establish appropriate immunotherapy strategies for elderly cancer patients.

2. Nectins and Nectin-Like Molecules

Nectins and Nectin-like molecules (Necls) are part of a broad group of cell adhesion proteins along with selectins, mucins, cadherins, integrins, and other cell adhesion molecules from the immunoglobulin superfamily. Nectins and Necls proteins mediate adhesion between cells independently of Ca2+. Nectins were originally described as molecules homologous to poliovirus receptors (PRR-1/2) and later renamed with the Latin word “necto,” which means to connect[6-8].

Currently the family of Nectins comprises four members and up to five molecules in the Necls family (Table 1). These molecules exert different functions, including cell adhesion, movement, proliferation, differentiation and survival. Thus, Nectins and Necls promote adhesion between cells of the same cell type (homotypical) and between cells of different types (heterotypical). This action can be performed independently or in cooperation with cadherins to promote changes in the cytoskeleton that reinforce cell-cell junctions, and these mechanisms are part of adherent junctions and tight junctions between neighboring epithelial cells[6,9,10].

| Members | Other names | Recognized by immunoreceptors | |

| Nectin | Nectin-1 | PVRL-1; CD111 | TACTILE (CD96) |

| Nectin-2 | PVRL-2; CD112 | DNAM-1; TIGIT; PVRIG (CD112R) | |

| Nectin-3 | PVRL-3; CD113 | TIGIT | |

| Nectin-4 | PVRL-4; PRR4 | ||

| Necl | Necl-1 | SynCAM-1; Cadm-3 | |

| Necl-2 | SynCAM-2; Cadm-1, TSLC1 | CRTAM | |

| Necl-3 | SynCAM-3; Cadm-2 | ||

| Necl-4 | SynCAM-4; Cadm-4 | ||

| Necl-5 | SynCAM-5; Cadm-5; CD155; PVR | DNAM-1; TACTILE (CD96); TIGIT |

PVR: poliovirus receptor; TACTIL: T cell activation increased late expression; DNAM-1: DNAX accessory molecule-1; TIGIT: T cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains; PVRIG: poliovirus receptor related immunoglobulin domain containing; PRR: poliovirus receptors.

2.1 Molecular structure of Nectins and Nectin-like molecules

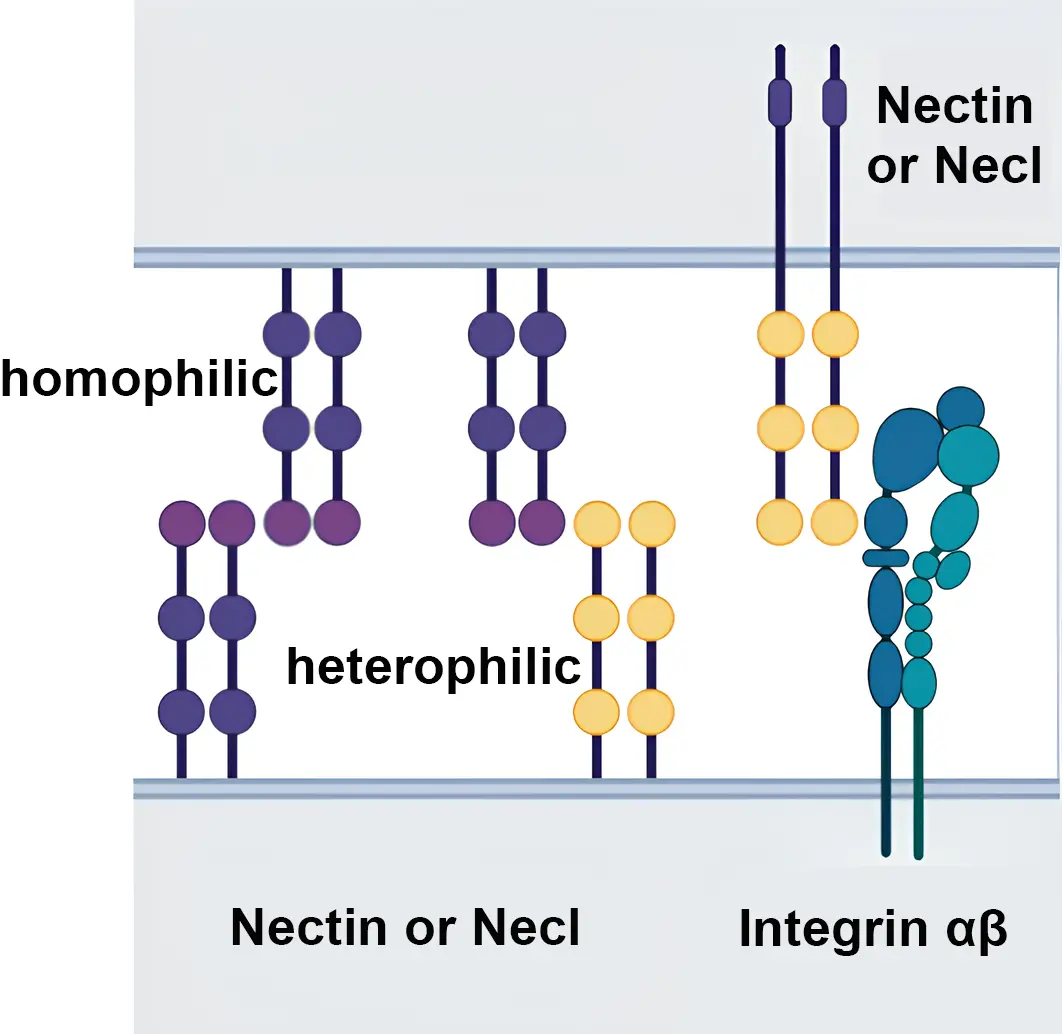

Nectins and Necls share a similar structure, three loop-shaped immunoglobulin-type domains, followed by a transmembrane region and a terminal cytoplasmic tail that, in the case of Nectins 1, 2 and 3, binds to the PDZ domain of afadin, a filament-binding protein essential for cell-cell interactions, in the neighboring cell. Although Necls share a cognate structure with Nectins, they lack afadin binding motifs and instead interact with distinct binding proteins such as membrane-associated gualinate kinase or members of the Band 4.1 family[7,8,11]. In the extracellular domain of Nectins and Necls, two molecules can interact in the same cell to form cis-dimers, that can be between the same (homophilic) or different (heterophilic) members of the Nectin or Necl families (Figure 1). These interactions can promote the formation and splicing of homophilic or heterophilic trans-dimers that adhere to the opposite cell, being the trans-heterophilic junction, the one with the highest affinity[9,12,13].

Figure 1. Nectin and Nectin-like molecules. Homophilic and heterophilic interactions are represented. Nectin molecules can also interact with other adhesion molecules such as integrins. Created with BioRender.com.

2.2 Tissue distribution and physiological function

Nectins and Necl molecules are expressed in a wide variety of tissues and adult cells. Nectins-1-2-3 are found in epithelial cells, fibroblasts, and neurons[13]. Nectin-2 (hereinafter referred to as CD112) is expressed in bone marrow, lung, kidney, pancreas, and Nectin-3 (hereinafter referred to as CD113) is expressed in lung, placenta, liver, and kidney[6,14,15]. CD112 and CD113 are strongly expressed in the testes[16] and are vital for spermatogenesis, forming crucial connections with Necl-2 in Sertoli and spermatid cells that promote germ cell development and differentiation[17,18]. Nectin-4 is expressed abundantly in embryonic and placenta tissues and has little expression in healthy adult tissue[19].

Several studies emphasize the physiological role of Nectin and Nectin-like molecules in the nervous system. Thus, nectin-1 and nectin-3 play a key role in the development of neural tissues, promoting the formation of synapses in adult central and peripheral neurons. In the hippocampus, these Nectin molecules have been implicated in synaptic plasticity and are also found in the auditory epithelium[20,21]. Regarding Nectin-like molecules, Necl-1-2-3-4 molecules interact in the peripheral nervous system. Heterophilic interactions between Necl-1 expressed on axonal cells and Necl-4 on Schwann cells promote the myelination process. Necl-1 and Necl-3 binding to Necl-4 favor neuron-glia interactions in both the central and peripheral nervous system[22-24].

In addition, Necl-1-2-4 are widely distributed in healthy tissues of the small intestine, lung and colon[25], and Necl-2-4-5 are expressed in the testes[26]. Necl-5 (hereinafter referred to as CD155) has low expression in most adult organs, but is abundant in fetal liver cells and in cancer cells and tumor cell lines, being considered as an oncofetal molecule that favors embryonic development and cancer progression[13,27].

Nectins and Necl molecules participate in cell adhesion and differentiation at different locations. Thus, trans-heterophilic interactions of either nectin-3 or -4 with nectin-1 occur in the auditory epithelium[21]. Nectin and Necl adhesion molecules participate in the cross-talk among integrin, cadherin and growth factor receptors contributing to the regulation of many cellular functions[9]. CD155 downregulation after contact with Nectin-3 supports its contribution to the phenomenon known as contact inhibition of cell movement and proliferation, that occurs in healthy cells but is frequently lost in transformed cell lines[13,28,29].

2.3 Nectins and Nectin-like molecules in solid tumors and hematological malignancies

In addition to the physiological role of Nectin and Necl proteins in cell adhesion, movement, and differentiation, their expression has also been related to cancer. The evidence shows an increase in several Nectins and Necls molecules in different types of cancer[1,11].

CD112 is overexpressed in breast, ovary, and pancreas cancer cells[30,31]. Thus, the use of anti-CD112 monoclonal antibodies in vitro against several tumor cell lines promoted antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity (ADCC), postulating CD112 as a potential target for antibody-mediated therapy in breast and ovarian cancers[31].

Nectin-4 is expressed in various types of cancer, including bladder, breast, lung, and ovarian cancer, and has been linked to a poor prognosis[19,32]. Enfortumab vedotin, an antibody-drug conjugate targeting Nectin-4, has been studied in several preclinical cancer models[33] and has been approved for its use in urothelial cancer[34,35].

As previously described, the expression of CD155 is minimal in adult tissues, but it is overexpressed in various types of cancer such as colon, pancreas, melanoma and glioblastoma[36-39], where it can contribute to the motility and proliferation of tumor cells[40].

A meta-analysis to evaluate the significance of CD155 expression in cancer prognosis has been performed involving 4325 cancer patients distributed across 26 studies. This study revealed that higher levels of CD155 are significantly associated with reduced overall survival in patients with some types of cancer (digestive cancer, hepatobiliary pancreatic cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer, head and neck cancer) compared with those with low CD155 expression. High expression of CD155 was correlated with advanced tumor stage and the presence of lymph node metastasis, and distant metastasis, whereas no significant association was reported for tumor size, TNM stage, or histological grade[41]. In patients with cholangiocarcinoma, the expression of CD155 was related to histological grade, lymph node metastasis, and TNM stage, and higher levels were associated with poor prognosis[42].

Studies of CD112 and CD155 expression on hematological malignances are more limited. In acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells, it has been shown that their expression is associated with poor prognosis, and their blockade augments T cell mediated lysis of AML[43,44]. CD155 is highly expressed in AML (especially AML with t(15;17) and t(8;21) translocations) and in chronic lymphoid leukemia[45]. CD155 is also highly expressed in patients with multiple myeloma and is related to tumor stage and poor prognosis[46]. In vitro studies have shown that FLT3 inhibitors suppress CD112 and CD155 expression on leukemic cells with FLT3 mutations and enhance NK cell mediated cytotoxicity and ADCC[47].

In contrast, some Necls proteins have been identified as tumor suppressors[11]. Thus, Necl-1 and Necl-4 suppress tumorigenicity in colon cancer and improves apoptosis rates of cancer cells[25]. CRTAM (Cytotoxic and Regulatory T cell-Associated Molecule), expressed in activated NK and T cells, interacts with Necl2/TSLC1 (tumor suppressor in lung cancer-1, TSLC1) on tumor cells, and this interaction results in NK cell cytotoxicity and interferon-γ secretion by CD8+ T cells[48].

3. Receptors for Nectin and Nectin-like Molecules

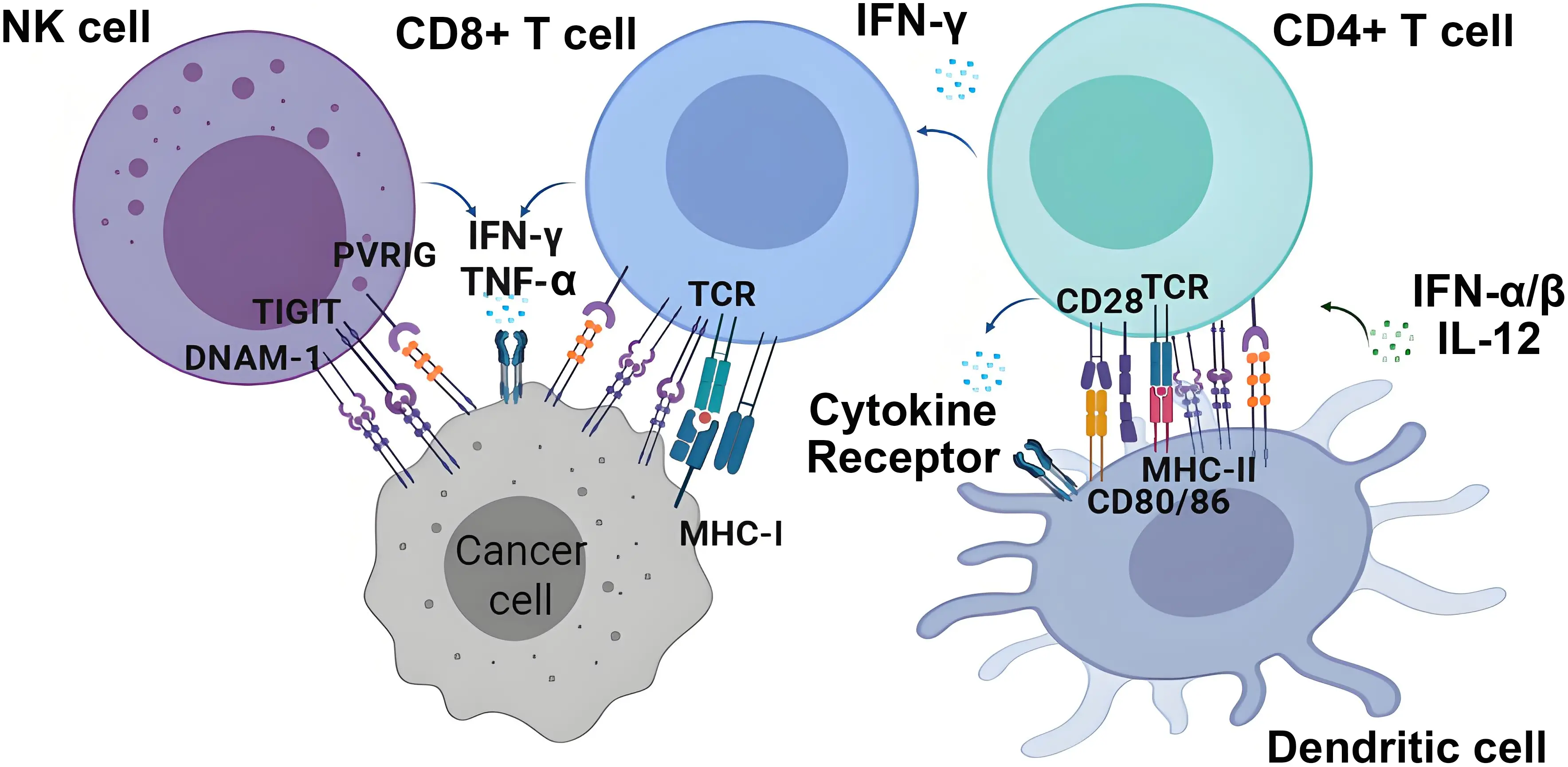

Nectin and Necls molecules are ligands for several immune receptors that exert different functions on T and NK cell activation (Table 1). Interestingly, CD155 and CD112 are ligands for both the activating/co-stimulatory receptor DNAM-1 and the inhibitory receptor TIGIT, establishing an axis of paired receptors that control, at least in part, the activation of NK cells and T cells (Figure 2). CD112R (also known as poliovirus receptor related immunoglobulin domain containing (PVRIG)), a receptor for CD112, and TACTILE, a receptor for CD155, further contribute to the complexity of this axis[49-52].

Figure 2. Nectin and Nectin-like molecules and their receptors. Nectin and Necl molecules, frequently overexpressed in cancer cells, interact with the activating/costimulatory receptor DNAM-1 on NK cells and T cells and with inhibitory receptors such as TIGIT or CD112R (PVRIG). The signaling through these activating and inhibiting receptors, together with other receptors involved in the activation of T and NK cells, will determine their degree of activation against cancer cells. In addition, the expression of Nectin and Nectin-like molecules in dendritic cells can contribute to the activation of CD4+ T cells and secretion of cytokines. Created with BioRender.com. DNAM-1: DNAX accessory molecule-1; NK: natural killer; TIGIT: T cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains; PVRIG: poliovirus receptor related immunoglobulin domain containing.

3.1 DNAM-1

3.1.1 DNAM-1 identification and structure

DNAM-1 (CD226) was originally identified as TLiSA-1, a specific marker of human T lineage involved in the differentiation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes[53], and afterward described as a glycoprotein involved in platelet aggregation and in the activation of platelets and T lymphocytes (PTA1)[54]. DNAM-1 is a ~65 kDa glycoprotein, a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily, encoded on the human chromosome 18 (18q22.3). DNAM-1 structure has three different domains: an extracellular domain of 230 amino acids with 2 Ig-like domains and eight potential N-linked glycosylation sites, a short transmembrane domain of 28 amino acids, and a third domain containing four tyrosine residues and one serine residue that are phosphorylated by intracellular kinases to induce cell activation[55].

Shibuya and colleagues showed that blocking DNAM-1 with the antibody DX11 inhibited T and NK cell-mediated lysis of tumor cell lines, supporting its role in T and NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity. This effect was partly explained by the functional relationship of DNAM-1 with LFA-1, an integrin essential for activation and cytotoxicity present in NK cells that favors adhesion to the target cell[56,57]. Today, it is known that DNAM-1 is an adhesion molecule and an activating co-receptor expressed by T cells and NK cells that plays a crucial role in antitumor immunity[50,58].

3.1.2 Expression and function of DNAM-1 on NK cells and T cells

DNAM-1 is widely expressed in CD8+ T cells, NK cells, monocytes, platelets, and a small subset of B cells[56,58,59]. CD112 and CD155 are DNAM-1 ligands both in human and mouse[60,61]. As stated above, these molecules are expressed in a variety of epithelial and endothelial tissues where they fulfill functions of adhesion, differentiation, proliferation, and movement, which are key for the development and function of healthy cells. NK cells participate in the lysis of immature dendritic cells through recognition of CD112 and CD155 by DNAM-1, which acts in cooperation with the activating receptor NKp30 to facilitate progression to a more mature phenotype and achieve fully functional antigen-presenting cells. The cytotoxic capacity mediated by DNAM-1 correlates with the surface density of these two ligands[62,63]. In solid or hematological tumors, CD112 and CD155 are overexpressed and may favor cancer progression and are associated with poor prognosis[11,31,38,64,65].

The clinical relevance of DNAM-1 and its role in NK cell-dependent tumor immunosurveillance has been described in various types of cancer[50]. DNAM-1 also participates in the control of viral infections mediated by NK cells[58,66]. DNAM-1 contributes to cytokine secretion and immune synapse in T and NK cells[56,58].

The interaction of DNAM-1 expressed on NK cells with tumor cells expressing CD112 and CD155 activates cytotoxicity and cytokine production against melanoma, neuroblastoma and hematological tumors of myeloid origin, among others[60,61,67]. It was reported that the soluble form of CD155 (sCD155), that is overexpressed in some cancer patients, suppressed DNAM-1-mediated degranulation of NK cells. It is speculated that sCD155 competes with membrane-expressed CD155 to bind DNAM-1, thus suppressing the antitumor immunity of NK cells[68,69]. In T cells, in addition to acting as a costimulatory molecule, DNAM-1 activates tyrosine phosphorylation pathways, which facilitate primary cell adhesion during cytotoxicity mediated by CD8+ T cells[56]. A study showed that CD8+ T cells require DNAM-1 for costimulation when the antigen is presented by non-professional antigen presenting cells, but not when the antigen is presented by dendritic cells[70].

3.2 TIGIT

3.2.1 TIGIT identification and structure

TIGIT (also called WUCAM, Vstm3, or VSIG) is an inhibitory receptor that shares CD112 and CD155 ligands with DNAM-1 but exerts opposite functions[50,71]. It was discovered in 2009 in a genomic search for proteins with immunoregulatory characteristics in T cells[72]. After binding to its ligands on target cells, TIGIT inhibits the activation of T cells and NK cells. As described previously, TIGIT is part of a complex immune regulation axis together with the DNAM-1, TACTILE and PVRIG receptors[50,72].

TIGIT contains an immunoglobulin extracellular variable domain, a type I transmembrane domain, a short intracellular cytoplasmic tail containing a tyrosine-based motif (ITIM), and an inhibitory signal-transducing Ig-tyrosine tail-like motif (ITT)[72,73]. Analysis of TIGIT interaction with CD155 showed that two TIGIT/CD155 dimers can assemble to form a heterotetramer[73].

3.2.2 Expression and function of TIGIT on NK cells and T cells

TIGIT is expressed on immune cells including CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, regulatory T cells, follicular T helper cells and NK cells[15,74-76]. Its expression is low in naïve cells and is upregulated after activation in both T cells and NK cells[71,72]. TIGIT is co-expressed together with PD-1 in tumor infiltrating CD8+ lymphocytes in melanoma[71]. In hematological tumors, an upregulation has been described in chronic lymphocytic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, and Sézary syndrome[77-79].

TIGIT shares the ligands CD112 and CD155 with DNAM-1. TIGIT has a higher affinity for CD155 than DNAM-1 and therefore plays a pivotal role in suppressing T and NK cell activation. Binding of TIGIT to CD155 suppresses IFN-γ production and cytotoxicity of NK cells in vitro[15,72,80,81]. TIGIT also interacts with the nectins CD112 and CD113, which have a lower affinity compared to CD155.

High expression of TIGIT in NK cells has been reported to protect liver regeneration by promoting NK cell tolerance, inhibiting their activation, and decreasing IFN-γ production after coupling to its ligand on the hepatocyte[82]. However, this regulatory effect in most cases promotes the progression of neoplastic diseases[83,84]. The double intracellular domain of ITIM and ITT in the cytoplasmic tail of TIGIT exerts a powerful inhibitory effect on both innate and adaptive immunity, compromising cytotoxicity and cytokines production[15,75,81,85]. TIGIT can exert its inhibitory effect on effector T cells and NK cells by several mechanisms. In an extrinsic way, TIGIT interaction with CD155 on dendritic cells activates signaling cascades that induce the secretion of IL-10 and a decrease in IL-12 production, promoting the formation of tolerogenic dendritic cells that control T cell activation[72]. TIGIT can also act in an intrinsic way by inhibiting T cell proliferation and function[75,86]. In addition, the higher affinity of TIGIT for binding to CD155 than DNAM-1 hinders the activation of DNAM-1 by interrupting its homodimerization and also by interfering with DNAM-1 binding to CD155[72,87].

Aging has been associated with changes in immune cells limiting immune response and cancer immunosurveillance, consequently favoring cancer progression[4,5]. Increased expression of TIGIT on T and NK cells has been shown to be associated with a state of cell exhaustion together with other inhibitory receptors, including PD-1[88]. This co-expression is a common feature of T cell exhaustion, where these cells lose their ability to effectively fight against pathogens or tumors.

In triple-negative breast cancer, TIGIT expression correlates with histologic grade and age[89]. TIGIT expression on T cells is frequently associated with other inhibitory receptors such as PD-1, hindering the immune response. In addition, downregulation of DNAM-1 is also observed associated with aging further contributing to the dysfunction of the immune system observed in the elderly[50,88,90].

3.3 TACTILE (CD96)

3.3.1 TACTILE identification and structure

TACTILE (T cell-activated increased late expression) is another member that is part of the immunological checkpoints that interacts with Nectins and Necls[91]. It was first identified in 1992 as a molecule expressed in T cells and involved in adhesion to target cells, activation, and cytotoxicity[92,93]. However, years later, Mark Smyth’s group discovered its inhibitory properties after observing that TACTILE (CD96) gene knockout mice were resistant to the induction of lung cancer and metastasis[94].

TACTILE belongs to the immunoglobulin superfamily and has three extracellular Ig-like domains and a cytoplasmic domain containing a short ITIM-like motif involved in its inhibitory function[95]. The structure of TACTILE is more complex than those of DNAM-1 and TIGIT, it presents two splice variants that differ in the extracellular domain due to the presence or absence of exon 4 in the mature mRNA[96]. In addition, close to the membrane there is a stem rich in proline, serine and threonine, common to other receptors such as CD44 or CD8α/β, although the short cytoplasmic motif is rich in proline with a single ITIM domain in both mouse and human. In contrast, only human TACTILE includes, at the end of this domain, a YXXM motif similar to those of the activation receptors CD28 and ICOS-1 that can be responsible for conferring the activating capacity also described for TACTILE[97,98].

3.3.2 Expression and function of TACTILE on NK cells and T cells

TACTILE is expressed in umbilical cord and bone marrow derived hematopoietic stem cells[99]. Its expression is mostly limited to immune cells such as T cells, both αβ and γδ, (increasing its level after activation), NK cells, and at lower levels in activated B cells[92,95]. TACTILE has also been described as a specific marker for leukemic stem cells in acute myeloid leukemia[96,100] and is highly expressed in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes[101,102].

The binding affinity of CD155 to TACTILE is lower than to TIGIT but higher than to DNAM-1, so it would be sufficient to cancel DNAM-1-mediated costimulatory signals[72,101].

In mice, CD111 (nectin-1) has been identified as a ligand for TACTILE[103]. It has been proposed that TIGIT and TACTILE act complementarily on NK cell effector function upon binding to their ligands[104]. In co-culture with CD155+CD9+ myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), only TIGIT blockade was able to restore human NK cell function, whereas TACTILE blockade did not[105].

TACTILE was originally reported to mediate adhesion and cytotoxicity of NK cells against tumor targets[93]. Over time, it was discovered that CD96-/- mice produced more IFN-γ, and in three induced tumor models, these mice were more resistant to tumor growth and metastasis. This effect was dependent on NK cells and DNAM-1 signaling[94,106]. In the same study by Chan et al.[94], TACTILE was shown to compete with DNAM-1 for binding to CD155 and to negatively regulate IFN-γ production in NK cells. A study that compared three anti-mouse TACTILE antibodies, two that block TACTILE-CD155 interaction (3.3 and 6A6) and one that does not (8B10), showed that although the potency of the two blocking antibodies was higher, the mice treated with the non-blocking antibody retained the antimetastatic activity dependent on NK cells and IFN-γ production, suggesting that the antitumor activity of NK cells may be preserved despite signaling through TACTILE[107]. The analysis of TACTILE in human hepatocarcinoma showed that TACTILE+ infiltrating NK cells display signs of functional exhaustion and decreased production of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-10 and TGF-β1, IL-15, Perforin and Granzyme B, and low T-bet expression[108].

Combined blockade of TIGIT and TACTILE has been suggested to enhance the cytotoxic functions of NK cells[109]. In NK cells, TIGIT mainly regulates cytotoxic function and TACTILE regulates the production of IFN-γ[104]. TACTILE is expressed on T cells in primary and metastatic human tumors, and the blockade of TACTILE suppressed the growth of experimental tumors in mouse models[110,111]. Gene expression analysis of tumors showed that TACTILE (CD96) expression correlates with CD8+ T cells and NK cell infiltration. However, the role of TACTILE within the tumor microenvironment remains elusive[111].

To elucidate its role in oncogenesis, a study in the Cancer Genome Atlas database analyzed the expression profile of the TACTILE gene in various solid tumors. Increased expression was found in esophageal carcinoma, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, kidney renal carcinoma, and stomach adenocarcinoma, while decreased expression was observed in breast invasive carcinoma, colon adenocarcinoma, lung squamous cell carcinoma, rectum adenocarcinoma, skin cutaneous melanoma, and thyroid carcinoma compared to healthy tissues. It is of interest to note that correlation analysis yielded contradictory results. High TACTILE expression was associated with a worse prognosis in lower grade glioma, uveal melanoma, and glioblastoma multiforme. On the contrary, low expression of TACTILE was associated with a protective effect in skin cutaneous melanoma, thymoma, bladder cancer, and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. In addition, in some types of cancer, the expression of TACTILE was positively correlated with the presence of immune infiltrates[112]. These findings suggest that TACTILE may play a dual immunoregulatory role in the tumor microenvironment and will require further analysis.

3.4 PVRIG

3.4.1 PVRIG identification and structure

PVRIG (poliovirus receptor-related immunoglobulin domain-containing protein), also known as CD112R, was identified in 2016 as an additional member of the inhibitory receptor axis complex that competes with DNAM-1 for the same ligands[113]. PVRIG contains a single IgV-like extracellular domain, a transmembrane domain, and a long intracellular domain that has two tyrosine residues, one of which is located within an ITIM-like motif. Human and mouse PVRIG share a similarity of more than 65% in the sequence of their extracellular IgV domain[113].

3.4.2 Expression and function of PVRIG on NK cells and T cells

PVRIG is expressed on T cells (predominantly effector and memory CD8+ cells) and NKT-like cells, while its expression is almost non-existent in naïve T cells. Human monocyte-derived dendritic cells, monocytes, neutrophils, and B cells from fresh blood do not express PVRIG. Upon activation, it is upregulated in T cells, including the CD4+ helper T cells. In peripheral blood NK cells, its expression is broad, including CD16− and CD16+ NK subpopulations[113,114].

CD112 (PVRL2 or Nectin-2) is so far the only known PVRIG ligand[113,114]. CD112 expression is increased in several types of cancer such as breast, ovary, pancreas, endometrial, lung, kidney, breast and prostate[49]. PVRIG enters into competition with TIGIT and DNAM-1 for binding to CD112. PVRIG binding to CD112 is stronger than that of DNAM-1 and TIGIT, and its interaction with CD112 ensures a preeminence of inhibitory signals over activating ones[91].

The study of PVRIG function on human NK cells is still incomplete. In an in vitro experiment, Xu et al.[114] demonstrated the inhibitory function of PVRIG using anti-PVRIG antibodies. They managed to increase the cytotoxic function of NK cells against a breast cancer cell line both by blocking PVRIG alone and even more by blocking PVRIG and TIGIT together. In a trial with infiltrating lymphocytes from human tumors, blocking PVRIG alone or in combination with TIGIT or PD-1 increased T-cell activation, where the inhibitory effect of CD112 was mediated by PVRIG and not by TIGIT[49]. In addition, the blockade of PVRIG and PD-1 in T lymphocytes improved the cytotoxic activity and the response to mouse tumor models[115]. In AML patients, a significant improvement in the activation and degranulation of NK cells against primary blasts expressing CD112 was observed after antibody-mediated blockade of PVRIG[52]. This evidence points to PVRIG as a co-inhibitory receptor that, together with TIGIT and TACTILE, competes for its ligands with the activating receptor DNAM-1 to establish an inhibitory dominance over T and NK cell functions.

Thanks to advances in the study of the Nectin family of molecules and their immune receptors, this axis now represents a new therapeutic target for cancer treatment. In this sense, blocking TIGIT and PVRIG, as monotherapy or in combination with other immunotherapy strategies, will likely be a line of action against cancer in the near future. The identification of immunological biomarkers that allow the selection of patients who may benefit from these treatments is a current line of research and is essential for the success of these therapies.

4. Aging and Its Impact on the Expression of Nectins, Necls and Their Immune Receptors

There is little information available on how aging can directly affect the expression of Nectin and Nectin-like molecules. Most studies analyze the expression of these molecules in age-related pathologies such as cancer, but do not describe the possible changes in their expression associated with age.

A meta-analysis involving 4,325 cancer patients to evaluate the role of CD155 expression in different types of cancer showed that high expression of CD155 was associated with advanced tumor stage and poor prognosis, whereas no significant association between the expression of CD155 and patients’ age was observed[41]. Similar results were described in another study in patients with cholangiocarcinoma[42]. The use of mass spectrometry has allowed the identification of distinct populations of senescent cells characterized by high levels of CD112[116] and its contribution to age-related pathologies is discussed. In general, as far as we currently know, the expression of these molecules in tumors is not associated with the patients’ age.

In humans, aging forces innate and adaptive immune remodeling and dysfunction, contributing to a poor response to vaccines, and increased susceptibility to infections and cancer[117-119]. This event, known as “immunosenescence”, was first described by Roy Walford in 1964[120]. Several research groups, including ours, have reported age-related changes in NK and T cell receptors[121-126].

Although direct studies on the effect of aging on the expression of Nectin and Nectin-like molecules and their receptors are limited, it is worth noting that findings in conditions of immune dysregulation linked to aging, such as chronic infections and cancer, are well documented. In this context, our group studied DNAM-1 in NK cells and T cells, observing a decreased expression in patients newly diagnosed with AML compared to healthy controls[51,127]. The expression of DNAM-1 on NK cells correlated with CD112 expression on AML blasts[127]. A reduced expression of DNAM-1 has been demonstrated on NK cells from elderly healthy donors compared with young healthy individuals[128].

The inhibitory receptor TIGIT has been analyzed as a biomarker of immunosenescence in CD8+ T cells. Thus, TIGIT+CD27−CD28− cell subsets progressively accumulate during aging[90,129]. Age was associated with increased TIGIT expression on CD8+ T cells, that is frequently found co-expressed with other inhibitory receptors such as PD-1, characteristic of exhausted cells[88,90]. In addition, aged TIGIT+ CD8+ T cells show downregulation of DNAM-1, further contributing to a defective immune response. It has been demonstrated in vitro that TIGIT knockdown reverts age-associated functional defects of these cells[90]. Consistent with this, antibody blockade of TIGIT increased the functional capacity of NK cells expressing high levels of this inhibitory receptor[130]. Similarly, another study observed that TIGIT blockade enhanced cytotoxicity in dysfunctional NK cells against CD155-transfected CD4+ T cells in HIV-1 patients and concluded that HIV-1 reactivation in CD4+ cells increased CD155 expression[131]. Consequently, as described in previous sections, in patients with solid and hematologic malignancies, high TIGIT expression in T and NK cells is associated with a poor prognosis[132-134]. In triple-negative breast cancer, TIGIT expression has been correlated with age and histologic grade[89].

These findings support the role of TIGIT as a relevant immune regulator during aging and cancer. Further studies are needed to establish TIGIT blockade protocols in elderly individuals to improve age-related immune dysfunction and optimize its efficacy in cancer patients.

Another relevant receptor involved in this regulatory axis is PVRIG, whose expression has been reported to be increased on NK cells and T cells in cancer[49,52]. PVRIG expression is associated with a dysfunctional CD8+ T cell phenotype coupled with an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in multiple myeloma[135]. In fact, it has been suggested that PVRIG expression in CD8+ T cells induces an exhausted and senescent phenotype[49,136]. Blockade of these immunoregulatory axes is emerging as a promising therapeutic strategy to counteract tumor progression and reverse exhaustion and senescence in NK and T cells. Combined strategic blockade of PVRIG and PD-L1 in mouse models enhances the effector function of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes[137]. As a result, cytotoxicity and IFN-γ production were significantly increased in subpopulations of NK and CD8+ T cells, resulting in suppressed tumor growth[115].

The presence of an ITIM motif and a YXXM motif may confer inhibitory or activating functions to the TACTILE receptor. Thus, a role of TACTILE as a costimulatory molecule involved in the activation and enhancement of the cytotoxic capacity of CD8+ T cells has been described[97]. In HIV-infected patients, the TACTILE receptor is downregulated in subsets of CD8+ T lymphocytes with a CD28− CD57+ phenotype, which is associated with disease progression, suggesting that TACTILE downregulation could be involved in cellular senescence in T cells[138].

Since Nectin family members share common ligands, cross-regulation between the different CD155 (DNAM-1, TIGIT, TACTILE) and CD112 (DNAM-1, TIGIT, PVRIG) binding receptors cannot be excluded.

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Nectin and Necls, along with their associated immune receptors, form a crucial axis in the immune response. This axis includes inhibitory and activating receptors that share the same ligands, resulting in complex regulatory interactions. In the last decade, the role of this axis in the immune response against cancer has been highlighted. DNAM-1 and TIGIT share CD112 and CD155 as ligands, whereas TACTILE binds to CD155 and PVRIG binds to CD112. A delicate balance of forces, through these signaling pathways, contributes to NK cells and T cell function and tumor control. Understanding this axis, including the binding mechanisms and specificities of these receptors, is crucial for the development of effective immunotherapies. The contradictory role of TACTILE in different types of cancers requires further analysis. Its structure, containing a tyrosine-based inhibitory motif as well as an activation motif, may explain the differences observed in different clinical settings.

Collectively, these findings suggest that malignant neoplasms with high expression of Nectins and Necls may induce functional deficiency in NK cells and T cells, therefore contributing to cancer immune evasion and leading to a state of immune decline characteristic of immunosenescence. The observed changes in the expression of Nectin family molecules and their immune receptors in cancer patients highlight the constant antigenic pressure faced by the immune system within the tumor microenvironment, the mechanisms underlying immune dysfunction, and the struggle for survival.

The major scientific and technological advances developed over the last decade have allowed for a better understanding of the immune mechanisms involved in the recognition and destruction of cancer cells. Age is a risk factor for the development of many cancers, and many challenges remain to be resolved for the adequate treatment of elderly patients. Promising directions for future research include the use of combinatorial blockade strategies to overcome treatment resistance, the identification of biomarkers of therapeutic success in elderly patients, and a better understanding of how the aged TME affects the response to cancer therapies. These future advances will contribute to the development of age-specific personalized treatments for better patient outcomes. These novel approaches aim to move beyond single treatments, adapting therapies to individual cancer cell biology, especially considering the unique challenges and immune landscape in older adults, and will help to develop new immunotherapy procedures to achieve longer life expectancies and better quality of life in advanced-age cancer patients.

Authors contribution

López-Sejas N, Tarazona R: Conceptualization, methodology, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing.

Solana R, Hassouneh F: Conceptualization, methodology, writing-review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

Raquel Tarazona and Rafael Solana are the Editorial Board Members of Ageing and Cancer Research & Treatment. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by Grants GR24081 to Group “Inmunopatología Tumoral” and research project IB20132 funded by Consejería de Economía, Ciencia y Agenda Digital (now Consejería de Educación, Ciencia y Formación Profesional) from Junta de Extremadura, Spain (to Raquel Tarazona); Project SAF2017-87538-R from Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, Spain (to Raquel Tarazona); Project PI21/01125 (to Rafael Solana) funded by Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) and PECART 0060-2020 (to Rafael Solana) from Secretaría General de Investigación, Desarrollo e Innovación en Salud, Junta de Andalucía, Spain. All co-financed by the European Union, European Regional Development Fund (FEDER) “Una manera de hacer Europa”. Postdoctoral fellowship (reference DOC_01421 to Fakhri Hassouneh) from Regional Ministry of Economic Transformation, Industry, Knowledge, and Universities of the Junta de Andalucía co-financed by the European Social Fund (ESF) under the Youth Employment Operational Programme 2014-2020, “The ESF invests in your future”.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

References

-

1. Murakami K, Ganguly S. The Nectin family ligands, PVRL2 and PVR, in cancer immunology and immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1441730.[DOI]

-

2. Holder AM, Dedeilia A, Sierra-Davidson K, Cohen S, Liu D, Parikh A, et al. Defining clinically useful biomarkers of immune checkpoint inhibitors in solid tumours. Nat Rev Cancer. 2024;24(7):498-512.[DOI]

-

3. Liu W, Zhou H, Lai W, Hu C, Xu R, Gu P, et al. The immunosuppressive landscape in tumor microenvironment. Immunol Res. 2024;72(4):566-582.[DOI]

-

4. Fulop T, Larbi A, Pawelec G, Khalil A, Cohen AA, Hirokawa K, et al. Immunology of aging: The birth of inflammaging. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2023;64(2):109-122.[DOI]

-

5. Pawelec G. The human immunosenescence phenotype: Does it exist? Semin Immunopathol. 2020;42(5):537-544.[DOI]

-

6. Satoh-Horikawa K, Nakanishi H, Takahashi K, Miyahara M, Nishimura M, Tachibana K, et al. Nectin-3, a new member of immunoglobulin-like cell adhesion molecules that shows homophilic and heterophilic cell-cell adhesion activities. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(14):10291-10299.[DOI]

-

7. Samanta D, Almo SC. Nectin family of cell-adhesion molecules: Structural and molecular aspects of function and specificity. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72(4):645-658.[DOI]

-

8. Miyoshi J, Takai Y. Nectin and nectin-like molecules: Biology and pathology. Am J Nephrol. 2007;27(6):590-604.[DOI]

-

9. Ogita H, Takai Y. Cross-talk among integrin, cadherin, and growth factor receptor: Roles of nectin and nectin-like molecule. Int Rev Cytol. 2008;265:1-54.[DOI]

-

10. Rikitake Y, Mandai K, Takai Y. The role of nectins in different types of cell-cell adhesion. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:3713-3722.[DOI]

-

11. Mandai K, Rikitake Y, Mori M, Takai Y. Nectins and nectin-like molecules in development and disease. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2015;112:197-231.[DOI]

-

12. Momose Y, Honda T, Inagaki M, Shimizu K, Irie K, Nakanishi H, et al. Role of the second immunoglobulin-like loop of nectin in cell-cell adhesion. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;293(1):45-49.[DOI]

-

13. Takai Y, Ikeda W, Ogita H, Rikitake Y. The immunoglobulin-like cell adhesion molecule nectin and its associated protein afadin. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2008;24:309-342.[DOI]

-

14. Reymond N, Borg JP, Lecocq E, Adelaide J, Campadelli-Fiume G, Dubreuil P, et al. Human nectin3/PRR3: A novel member of the PVR/PRR/nectin family that interacts with afadin. Gene. 2000;255(2):347-355.[DOI]

-

15. Stanietsky N, Simic H, Arapovic J, Toporik A, Levy O, Novik A, et al. The interaction of TIGIT with PVR and PVRL2 inhibits human NK cell cytotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 2009;106(42):17858-17863.[DOI]

-

16. Li T, Yao J, Zhang Q, Li Q, Li J, Wang X, et al. Chronic stress impairs male spermatogenesis function and Nectin-3 protein expression in the testis. Physiol Res. 2020;69(2):297-306.[DOI]

-

17. Ozaki-Kuroda K, Nakanishi H, Ohta H, Tanaka H, Kurihara H, Mueller S, et al. Nectin couples cell-cell adhesion and the actin scaffold at heterotypic testicular junctions. Curr Biol. 2002;12(13):1145-1150.[DOI]

-

18. Inagaki M, Irie K, Ishizaki H, Tanaka-Okamoto M, Miyoshi J, Takai Y. Role of cell adhesion molecule nectin-3 in spermatid development. Genes Cells. 2006;11(9):1125-1132.[DOI]

-

19. Nikanjam M, Pérez-Granado J, Gramling M, Larvol B, Kurzrock R. Nectin-4 expression patterns and therapeutics in oncology. Cancer Lett. 2025;622:217681.[DOI]

-

20. Tomorsky J, Parker PRL, Doe CQ, Niell CM. Precise levels of nectin-3 are required for proper synapse formation in postnatal visual cortex. Neural Dev. 2020;15(1):13.[DOI]

-

21. Togashi H, Kominami K, Waseda M, Komura H, Miyoshi J, Takeichi M, et al. Nectins establish a checkerboard-like cellular pattern in the auditory epithelium. Science. 2011;333(6046):1144-1147.[DOI]

-

22. Maurel P, Einheber S, Galinska J, Thaker P, Lam I, Rubin MB, et al. Nectin-like proteins mediate axon Schwann cell interactions along the internode and are essential for myelination. J Cell Biol. 2007;178(5):861-874.[DOI]

-

23. Pellissier F, Gerber A, Bauer C, Ballivet M, Ossipow V. The adhesion molecule Necl-3/SynCAM-2 localizes to myelinated axons, binds to oligodendrocytes and promotes cell adhesion. BMC Neurosci. 2007;8:90.[DOI]

-

24. Spiegel I, Adamsky K, Eshed Y, Milo R, Sabanay H, Sarig-Nadir O, et al. A central role for Necl4 (SynCAM4) in Schwann cell-axon interaction and myelination. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10(7):861-869.[DOI]

-

25. Raveh S, Gavert N, Spiegel I, Ben-Ze’ev A. The cell adhesion nectin-like molecules (Necl) 1 and 4 suppress the growth and tumorigenic ability of colon cancer cells. J Cell Biochem. 2009;108(1):326-336.[DOI]

-

26. Huang K, Lui WY. Nectins and nectin-like molecules (Necls): Recent findings and their role and regulation in spermatogenesis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2016;59:54-61.[DOI]

-

27. Molfetta R, Zitti B, Lecce M, Milito ND, Stabile H, Fionda C, et al. CD155: A multi-functional molecule in tumor progression. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(3):922.[DOI]

-

28. Fujito T, Ikeda W, Kakunaga S, Minami Y, Kajita M, Sakamoto Y, et al. Inhibition of cell movement and proliferation by cell-cell contact-induced interaction of Necl-5 with nectin-3. J Cell Biol. 2005;171(1):165-173.[DOI]

-

29. Kakunaga S, Ikeda W, Shingai T, Fujito T, Yamada A, Minami Y, et al. Enhancement of serum- and platelet-derived growth factor-induced cell proliferation by Necl-5/Tage4/poliovirus receptor/CD155 through the Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK signaling. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(35):36419-36425.[DOI]

-

30. Liang S, Yang Z, Li D, Miao X, Yang L, Zou Q, et al. The clinical and pathological significance of Nectin-2 and DDX3 expression in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas. Dis Markers. 2015;2015:379568.[DOI]

-

31. Oshima T, Sato S, Kato J, Ito Y, Watanabe T, Tsuji I, et al. Nectin-2 is a potential target for antibody therapy of breast and ovarian cancers. Mol Cancer. 2013;12:60.[DOI]

-

32. Sethy C, Goutam K, Nayak D, Pradhan R, Molla S, Chatterjee S, et al. Clinical significance of a pvrl 4 encoded gene Nectin-4 in metastasis and angiogenesis for tumor relapse. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2020;146(1):245-259.[DOI]

-

33. Challita-Eid PM, Satpayev D, Yang P, An Z, Morrison K, Shostak Y, et al. Enfortumab vedotin antibody-drug conjugate targeting nectin-4 is a highly potent therapeutic agent in multiple preclinical cancer models. Cancer Res. 2016;76(10):3003-3013.[DOI]

-

34. Rosenberg JE, Powles T, Sonpavde GP, Loriot Y, Duran I, Lee JL, et al. EV-301 long-term outcomes: 24-month findings from the phase III trial of enfortumab vedotin versus chemotherapy in patients with previously treated advanced urothelial carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2023;34(11):1047-1054.[DOI]

-

35. Heath EI, Rosenberg JE. The biology and rationale of targeting nectin-4 in urothelial carcinoma. Nat Rev Urol. 2021;18(2):93-103.[DOI]

-

36. Bevelacqua V, Bevelacqua Y, Candido S, Skarmoutsou E, Amoroso A, Guarneri C, et al. Nectin like-5 overexpression correlates with the malignant phenotype in cutaneous melanoma. Oncotarget. 2012;3(8):882-892.[DOI]

-

37. Enloe BM, Jay DG. Inhibition of Necl-5 (CD155/PVR) reduces glioblastoma dispersal and decreases MMP-2 expression and activity. J Neurooncol. 2011;102(2):225-235.[DOI]

-

38. Tane S, Maniwa Y, Hokka D, Tauchi S, Nishio W, Okita Y, et al. The role of Necl-5 in the invasive activity of lung adenocarcinoma. Exp Mol Pathol. 2013;94(2):330-335.[DOI]

-

39. Paolini R, Molfetta R. CD155 and its receptors as targets for cancer therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(16):12958.[DOI]

-

40. Ikeda W, Kakunaga S, Takekuni K, Shingai T, Satoh K, Morimoto K, et al. Nectin-like molecule-5/Tage4 enhances cell migration in an integrin-dependent, Nectin-3-independent manner. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(17):18015-18025.[DOI]

-

41. Zhang D, Liu J, Zheng M, Meng C, Liao J. Prognostic and clinicopathological significance of CD155 expression in cancer patients: A meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2022;20(1):351.[DOI]

-

42. Huang DW, Huang M, Lin XS, Huang Q. CD155 expression and its correlation with clinicopathologic characteristics, angiogenesis, and prognosis in human cholangiocarcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2017;10:3817-3825.[DOI]

-

43. Stamm H, Klingler F, Grossjohann EM, Muschhammer J, Vettorazzi E, Heuser M, et al. Immune checkpoints PVR and PVRL2 are prognostic markers in AML and their blockade represents a new therapeutic option. Oncogene. 2018;37(39):5269-5280.[DOI]

-

44. Abdalla AZ, Khallaf SM, Zahran AM, Rayan NA, Elzaher ARA. CD155 as a prognostic and predictive biomarker in acute myeloid leukemia. Discov Oncol. 2025;16(1):902.[DOI]

-

45. Meng F, Xiang M, Liu Y, Zeng D. TIGIT/PVR axis regulates anti-tumor immunity in hematologic malignancies. Ann Hematol. 2025;104(3):1415-1426.[DOI]

-

46. Lee BH, Kim JH, Kang KW, Lee SR, Park Y, Sung HJ, et al. PVR (CD155) expression as a potential prognostic marker in multiple myeloma. Biomedicines. 2022;10(5):1099.[DOI]

-

47. Kaito Y, Hirano M, Futami M, Nojima M, Tamura H, Tojo A, et al. CD155 and CD112 as possible therapeutic targets of FLT3 inhibitors for acute myeloid leukemia. Oncol Lett. 2022;23(2):51.[DOI]

-

48. Boles KS, Barchet W, Diacovo T, Cella M, Colonna M. The tumor suppressor TSLC1/NECL-2 triggers NK-cell and CD8+ T-cell responses through the cell-surface receptor CRTAM. Blood. 2005;106(3):779-786.[DOI]

-

49. Whelan S, Ophir E, Kotturi MF, Levy O, Ganguly S, Leung L, et al. PVRIG and PVRL2 are induced in cancer and inhibit CD8+ T-cell function. Cancer Immunol Res. 2019;7(2):257-268.[DOI]

-

50. Sanchez-Correa B, Valhondo I, Hassouneh F, Lopez-Sejas N, Pera A, Bergua JM, et al. DNAM-1 and the TIGIT/PVRIG/TACTILE axis: Novel immune checkpoints for natural killer cell-based cancer immunotherapy. Cancers. 2019;11(6):877.[DOI]

-

51. Valhondo I, Hassouneh F, Lopez-Sejas N, Pera A, Sanchez-Correa B, Guerrero B, et al. Characterization of the DNAM-1, TIGIT and TACTILE axis on circulating NK, NKT-like and T cell subsets in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Cancers. 2020;12(8):2171.[DOI]

-

52. Li J, Whelan S, Kotturi MF, Meyran D, D’Souza C, Hansen K, et al. Pvrig is a novel natural killer cell immune checkpoint receptor in acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2021;106(12):3115-3124.[DOI]

-

53. Burns GF, Triglia T, Werkmeister JA, Begley CG, Boyd AW. TLiSA1, a human T lineage-specific activation antigen involved in the differentiation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes and anomalous killer cells from their precursors. J Exp Med. 1985;161(5):1063-1078.[DOI]

-

54. Scott JL, Dunn SM, Jin B, Hillam AJ, Walton S, Berndt M, et al. Characterization of a novel membrane glycoprotein involved in platelet activation. J Biol Chem. 1989;264(23):13475-13482.[DOI]

-

55. Zhang Z, Wu N, Lu Y, Davidson D, Colonna M, Veillette A. DNAM-1 controls NK cell activation via an ITT-like motif. J Exp Med. 2015;212(12):2165-2182.[DOI]

-

56. Shibuya A, Campbell D, Hannum C, Yssel H, Franz-Bacon K, McClanahan T, et al. DNAM-1, a novel adhesion molecule involved in the cytolytic function of T lymphocytes. Immunity. 1996;4(6):573-581.[DOI]

-

57. Shibuya K, Lanier LL, Phillips JH, Ochs HD, Shimizu K, Nakayama E, et al. Physical and functional association of LFA-1 with DNAM-1 adhesion molecule. Immunity. 1999;11(5):615-623.[DOI]

-

58. de Andrade LF, Smyth MJ, Martinet L. DNAM-1 control of natural killer cells functions through nectin and nectin-like proteins. Immunol Cell Biol. 2014;92(3):237-244.[DOI]

-

59. Nagayama-Hasegawa Y, Honda SI, Shibuya A, Shibuya K. Expression and function of DNAM-1 on human B-lineage cells. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2020;98(4):368-374.[DOI]

-

60. Bottino C, Castriconi R, Pende D, Rivera P, Nanni M, Carnemolla B, et al. Identification of PVR (CD155) and Nectin-2 (CD112) as cell surface ligands for the human DNAM-1 (CD226) activating molecule. J Exp Med. 2003;198(4):557-567.[DOI]

-

61. Tahara-Hanaoka S, Shibuya K, Onoda Y, Zhang H, Yamazaki S, Miyamoto A, et al. Functional characterization of DNAM-1 (CD226) interaction with its ligands PVR (CD155) and nectin-2 (PRR-2/CD112). Int Immunol. 2004;16(4):533-538.[DOI]

-

62. Pende D, Castriconi R, Romagnani P, Spaggiari GM, Marcenaro S, Dondero A, et al. Expression of the DNAM-1 ligands, Nectin-2 (CD112) and poliovirus receptor (CD155), on dendritic cells: Relevance for natural killer-dendritic cell interaction. Blood. 2006;107(5):2030-2036.[DOI]

-

63. Ferlazzo G, Moretta L. Dendritic cell editing by natural killer cells. Crit Rev Oncog. 2014;19:67-75.[DOI]

-

64. El-Sherbiny YM, Meade JL, Holmes TD, McGonagle D, Mackie SL, Morgan AW, et al. The requirement for DNAM-1, NKG2D, and NKp46 in the natural killer cell-mediated killing of myeloma cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67(18):8444-8449.[DOI]

-

65. Nakanishi H, Takai Y. Roles of nectins in cell adhesion, migration and polarization. Biol Chem. 2004;385(10):885-892.[DOI]

-

66. Nabekura T, Kanaya M, Shibuya A, Fu G, Gascoigne NR, Lanier LL. Costimulatory molecule DNAM-1 is essential for optimal differentiation of memory natural killer cells during mouse cytomegalovirus infection. Immunity. 2014;40(2):225-234.[DOI]

-

67. Pende D, Bottino C, Castriconi R, Cantoni C, Marcenaro S, Rivera P, et al. PVR (CD155) and Nectin-2 (CD112) as ligands of the human DNAM-1 (CD226) activating receptor: Involvement in tumor cell lysis. Mol Immunol. 2005;42(4):463-469.[DOI]

-

68. Iguchi-Manaka A, Okumura G, Kojima H, Cho Y, Hirochika R, Bando H, et al. Increased soluble CD155 in the serum of cancer patients. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0152982.[DOI]

-

69. Okumura G, Iguchi-Manaka A, Murata R, Yamashita-Kanemaru Y, Shibuya A, Shibuya K. Tumor-derived soluble CD155 inhibits DNAM-1-mediated antitumor activity of natural killer cells. J Exp Med. 2020;217(4):e20190626.[DOI]

-

70. Gilfillan S, Chan CJ, Cella M, Haynes NM, Rapaport AS, Boles KS, et al. DNAM-1 promotes activation of cytotoxic lymphocytes by nonprofessional antigen-presenting cells and tumors. J Exp Med. 2008;205(13):2965-2973.[DOI]

-

71. Chauvin JM, Pagliano O, Fourcade J, Sun Z, Wang H, Sander C, et al. TIGIT and PD-1 impair tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in melanoma patients. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(5):2046-2058.[DOI]

-

72. Yu X, Harden K, Gonzalez LC, Francesco M, Chiang E, Irving B, et al. The surface protein TIGIT suppresses T cell activation by promoting the generation of mature immunoregulatory dendritic cells. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(1):48-57.[DOI]

-

73. Stengel KF, Harden-Bowles K, Yu X, Rouge L, Yin J, Comps-Agrar L, et al. Structure of TIGIT immunoreceptor bound to poliovirus receptor reveals a cell-cell adhesion and signaling mechanism that requires cis-trans receptor clustering. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 2012;109(14):5399-5404.[DOI]

-

74. Boles KS, Vermi W, Facchetti F, Fuchs A, Wilson TJ, Diacovo TG, et al. A novel molecular interaction for the adhesion of follicular CD4 T cells to follicular DC. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39(3):695-703.[DOI]

-

75. Joller N, Hafler JP, Brynedal B, Kassam N, Spoerl S, Levin SD, et al. Cutting edge: TIGIT has T cell-intrinsic inhibitory functions. J Immunol. 2011;186(3):1338-1342.[DOI]

-

76. Chauvin JM, Zarour HM. TIGIT in cancer immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8(2):e000957.[DOI]

-

77. Catakovic K, Gassner FJ, Ratswohl C, Zaborsky N, Rebhandl S, Schubert M, et al. TIGIT expressing CD4+ T cells represent a tumor-supportive T cell subset in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Oncoimmunology. 2017;7(1):e1371399.[DOI]

-

78. Kong Y, Zhu L, Schell TD, Zhang J, Claxton DF, Ehmann WC, et al. T-cell immunoglobulin and ITIM domain (TIGIT) associates with CD8+ T-cell exhaustion and poor clinical outcome in AML patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(12):3057-3066.[DOI]

-

79. Jariwala N, Benoit B, Kossenkov AV, Oetjen LK, Whelan TM, Cornejo CM, et al. TIGIT and Helios are highly expressed on CD4+ T cells in Sézary syndrome patients. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137(1):257-260.[DOI]

-

80. Stein N, Tsukerman P, Mandelboim O. The paired receptors TIGIT and DNAM-1 as targets for therapeutic antibodies. Hum Antibodies. 2017;25:111-119.[DOI]

-

81. Li M, Xia P, Du Y, Liu S, Huang G, Chen J, et al. T-cell immunoglobulin and ITIM domain (TIGIT) receptor/poliovirus receptor (PVR) ligand engagement suppresses interferon-γ production of natural killer cells via β-arrestin 2-mediated negative signaling. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(25):17647-17657.[DOI]

-

82. Chen MS, Kim H, Jagot-Lacoussiere L, Maurel P. Cadm3 (Necl-1) interferes with the activation of the PI3 kinase/Akt signaling cascade and inhibits Schwann cell myelination in vitro. Glia. 2016;64(12):2247-2262.[DOI]

-

83. Harjunpää H, Guillerey C. TIGIT as an emerging immune checkpoint. Clin Exp Immunol. 2020;200(2):108-119.[DOI]

-

84. Zhou XM, Li WQ, Wu YH, Han L, Cao XG, Yang XM, et al. Intrinsic expression of immune checkpoint molecule TIGIT could help tumor growth in vivo by suppressing the function of NK and CD8+ T cells. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2821.[DOI]

-

85. Liu S, Zhang H, Li M, Hu D, Li C, Ge B, et al. Recruitment of Grb2 and SHIP1 by the ITT-like motif of TIGIT suppresses granule polarization and cytotoxicity of NK cells. Cell Death Differ. 2013;20(3):456-464.[DOI]

-

86. Lozano E, Dominguez-Villar M, Kuchroo V, Hafler DA. The TIGIT/CD226 axis regulates human T cell function. J Immunol. 2012;188(8):3869-3875.[DOI]

-

87. Johnston RJ, Comps-Agrar L, Hackney J, Yu X, Huseni M, Yang Y, et al. The immunoreceptor TIGIT regulates antitumor and antiviral CD8+ T cell effector function. Cancer Cell. 2014;26(6):923-937.[DOI]

-

88. Xu L, Liu L, Yao D, Zeng X, Zhang Y, Lai J, et al. PD-1 and TIGIT are highly co-expressed on CD8+ T cells in AML patient bone marrow. Front Oncol. 2021;11:686156.[DOI]

-

89. Boissière-Michot F, Chateau MC, Thézenas S, Guiu S, Bobrie A, Jacot W. Correlation of the TIGIT-PVR immune checkpoint axis with clinicopathological features in triple-negative breast cancer. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1058424.[DOI]

-

90. Song Y, Wang B, Song R, Hao Y, Wang D, Li Y, et al. T-cell immunoglobulin and ITIM domain contributes to CD8+ T-cell immunosenescence. Aging Cell. 2018;17(2):e12716.[DOI]

-

91. Deuss FA, Watson GM, Fu Z, Rossjohn J, Berry R. Structural basis for CD96 immune receptor recognition of nectin-like protein-5, CD155. Structure. 2019;27(2):219-228.[DOI]

-

92. Wang PL, O’Farrell S, Clayberger C, Krensky AM. Identification and molecular cloning of tactile. A novel human T cell activation antigen that is a member of the Ig gene superfamily. J Immunol. 1992;148(8):2600-2608.[PubMed]

-

93. Fuchs A, Cella M, Giurisato E, Shaw AS, Colonna M. Cutting edge: CD96 (Tactile) promotes NK cell-target cell adhesion by interacting with the poliovirus receptor (CD155). J Immunol. 2004;172(7):3994-3998.[DOI]

-

94. Chan CJ, Martinet L, Gilfillan S, Souza-Fonseca-Guimaraes F, Chow MT, Town L, et al. The receptors CD96 and CD226 oppose each other in the regulation of natural killer cell functions. Nat Immunol. 2014;15(5):431-438.[DOI]

-

95. Feng S, Isayev O, Werner J, Bazhin AV. CD96 as a potential immune regulator in cancers. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(2):1303.[DOI]

-

96. Meyer D, Seth S, Albrecht J, Maier MK, du Pasquier L, Ravens I, et al. CD96 interaction with CD155 via its first Ig-like domain is modulated by alternative splicing or mutations in distal Ig-like domains. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(4):2235-2244.[DOI]

-

97. Chiang EY, de Almeida PE, de Almeida Nagata DE, Bowles KH, Du X, Chitre AS, et al. CD96 functions as a co-stimulatory receptor to enhance CD8+ T cell activation and effector responses. Eur J Immunol. 2020;50(6):891-902.[DOI]

-

98. Georgiev H, Ravens I, Papadogianni G, Bernhardt G. Coming of age: CD96 emerges as modulator of immune responses. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1072.[DOI]

-

99. Garg S, Madkaikar M, Ghosh K. Investigating cell surface markers on normal hematopoietic stem cells in three different niche conditions. Int J Stem Cells. 2013;6(2):129-133.[DOI]

-

100. Hosen N, Park CY, Tatsumi N, Oji Y, Sugiyama H, Gramatzki M, et al. CD96 is a leukemic stem cell-specific marker in human acute myeloid leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 2007;104(26):11008-11013.[DOI]

-

101. Gramatzki M, Ludwig WD, Burger R, Moos P, Rohwer P, Grünert C, et al. Antibodies TC-12 (“unique”) and TH-111 (CD96) characterize T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and a subgroup of acute myeloid leukemia. Exp Hematol. 1998;26(13):1209-1214.[PubMed]

-

102. Zhang W, Shao Z, Fu R, Wang H, Li L, Liu H. Expressions of CD96 and CD123 in bone marrow cells of patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Clin Lab. 2015;61(10):1429-1434.[DOI]

-

103. Seth S, Maier MK, Qiu Q, Ravens I, Kremmer E, Förster R, et al. The murine pan T cell marker CD96 is an adhesion receptor for CD155 and nectin-1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;364(4):959-965.[DOI]

-

104. Kim N, Kim HS. Targeting checkpoint receptors and molecules for therapeutic modulation of natural killer cells. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2041.[DOI]

-

105. Sarhan D, Cichocki F, Zhang B, Yingst A, Spellman SR, Cooley S, et al. Adaptive NK cells with low TIGIT expression are inherently resistant to myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Res. 2016;76(19):5696-5706.[DOI]

-

106. Blake SJ, Dougall WC, Miles JJ, Teng MW, Smyth MJ. Molecular pathways: Targeting CD96 and TIGIT for cancer immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(21):5183-5188.[DOI]

-

107. Roman Aguilera A, Lutzky VP, Mittal D, Li XY, Stannard K, Takeda K, et al. CD96 targeted antibodies need not block CD96-CD155 interactions to promote NK cell anti-metastatic activity. Oncoimmunology. 2018;7(5):e1424677.[DOI]

-

108. Sun H, Huang Q, Huang M, Wen H, Lin R, Zheng M, et al. Human CD96 correlates to natural killer cell exhaustion and predicts the prognosis of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2019;70(1):168-183.[DOI]

-

109. Dougall WC, Kurtulus S, Smyth MJ, Anderson AC. TIGIT and CD96: New checkpoint receptor targets for cancer immunotherapy. Immunol Rev. 2017;276(1):112-120.[DOI]

-

110. Mittal D, Lepletier A, Madore J, Aguilera AR, Stannard K, Blake SJ, et al. CD96 is an immune checkpoint that regulates CD8+ T-cell antitumor function. Cancer Immunol Res. 2019;7(4):559-571.[DOI]

-

111. Lepletier A, Lutzky VP, Mittal D, Stannard K, Watkins TS, Ratnatunga CN, et al. The immune checkpoint CD96 defines a distinct lymphocyte phenotype and is highly expressed on tumor-infiltrating T cells. Immunol Cell Biol. 2019;97(2):152-164.[DOI]

-

112. Ye W, Luo C, Liu F, Liu Z, Chen F. CD96 correlates with immune infiltration and impacts patient prognosis: A pan-cancer analysis. Front Oncol. 2021;11:634617.[DOI]

-

113. Zhu Y, Paniccia A, Schulick AC, Chen W, Koenig MR, Byers JT, et al. Identification of CD112R as a novel checkpoint for human T cells. J Exp Med. 2016;213(2):167-176.[DOI]

-

114. Xu F, Sunderland A, Zhou Y, Schulick RD, Edil BH, Zhu Y. Blockade of CD112R and TIGIT signaling sensitizes human natural killer cell functions. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2017;66(10):1367-1375.[DOI]

-

115. Murter B, Pan X, Ophir E, Alteber Z, Azulay M, Sen R, et al. Mouse PVRIG has CD8+ T cell-specific coinhibitory functions and dampens antitumor immunity. Cancer Immunol Res. 2019;7(2):244-256.[DOI]

-

116. Abdelmohsen K, Mazan-Mamczarz K, Munk R, Tsitsipatis D, Meng Q, Rossi M, et al. Identification of senescent cell subpopulations by CITE-seq analysis. Aging Cell. 2024;23(11):e14297.[DOI]

-

117. Fulop T, Larbi A, Witkowski JM, Kotb R, Hirokawa K, Pawelec G. Immunosenescence and cancer. Crit Rev Oncog. 2013;18(6):489-513.[DOI]

-

118. Xu W, Wong G, Hwang YY, Larbi A. The untwining of immunosenescence and aging. Semin Immunopathol. 2020;42(5):559-572.[DOI]

-

119. Chen L, Shao C, Li J, Zhu F. Impact of immunosenescence on vaccine immune responses and countermeasures. Vaccines. 2024;12(11):1289.[DOI]

-

120. Walford RL. The immunologic theory of aging. Gerontologist. 1964;4:195-197.[DOI]

-

121. Guo Z, Wu F, Chen Y, Xu J, Chen Z. Phenotypes, mechanisms, and therapeutic strategies of natural killer cell immunosenescence. Immun Ageing. 2025;22(1):38.[DOI]

-

122. Brauning A, Rae M, Zhu G, Fulton E, Admasu TD, Stolzing A, et al. Aging of the immune system: Focus on natural killer cells phenotype and functions. Cells. 2022;11(6):[DOI]

-

123. Jia Z, Ren Z, Ye D, Li J, Xu Y, Liu H, et al. Immune-ageing evaluation of peripheral T and NK lymphocyte subsets in Chinese healthy adults. Phenomics. 2023;3(4):360-374.[DOI]

-

124. Song N, Elbahnasawy MA, Weng NP. General and individualized changes in T cell immunity during aging. J Immunol. 2025;214(5):872-879.[DOI]

-

125. Solana R, Tarazona R, Gayoso I, Lesur O, Dupuis G, Fulop T. Innate immunosenescence: Effect of aging on cells and receptors of the innate immune system in humans. Semin Immunol. 2012;24(5):331-341.[DOI]

-

126. Rodriguez IJ, Lalinde Ruiz N, Llano León M, Martínez Enríquez L, Montilla Velásquez MDP, Ortiz Aguirre JP, et al. Immunosenescence study of T cells: A systematic review. Front Immunol. 2020;11:604591.[DOI]

-

127. Sanchez-Correa B, Gayoso I, Bergua JM, Casado JG, Morgado S, Solana R, et al. Decreased expression of DNAM-1 on NK cells from acute myeloid leukemia patients. Immunol Cell Biol. 2012;90(1):109-115.[DOI]

-

128. Campos C, López N, Pera A, Gordillo JJ, Hassouneh F, Tarazona R, et al. Expression of NKp30, NKp46 and DNAM-1 activating receptors on resting and IL-2 activated NK cells from healthy donors according to CMV-serostatus and age. Biogerontology. 2015;16(5):671-683.[DOI]

-

129. Pieren DKJ, Smits NAM, Postel RJ, Kandiah V, de Wit J, van Beek J, et al. Co-expression of TIGIT and Helios marks immunosenescent CD8+ T cells during aging. Front Immunol. 2022;13:833531.[DOI]

-

130. Wang F, Hou H, Wu S, Tang Q, Liu W, Huang M, et al. TIGIT expression levels on human NK cells correlate with functional heterogeneity among healthy individuals. Eur J Immunol. 2015;45(10):2886-2897.[DOI]

-

131. Holder KA, Burt K, Grant MD. TIGIT blockade enhances NK cell activity against autologous HIV-1-infected CD4+ T cells. Clin Transl Immunology. 2021;10(10):e1348.[DOI]

-

132. Xiao K, Xiao K, Li K, Xue P, Zhu S. Prognostic role of TIGIT expression in patients with solid tumors: A meta-analysis. J Immunol Res. 2021;2021(1):5440572.[DOI]

-

133. Liu G, Zhang Q, Yang J, Li X, Xian L, Li W, et al. Increased TIGIT expressing NK cells with dysfunctional phenotype in AML patients correlated with poor prognosis. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2022;71(2):277-287.[DOI]

-

134. Zeng X, Yao D, Liu L, Zhang Y, Lai J, Zhong J, et al. Terminal differentiation of bone marrow NK cells and increased circulation of TIGIT+ NK cells may be related to poor outcome in acute myeloid leukemia. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2022;18(4):456-464.[DOI]

-

135. Frenkel M, Alteber Z, Xu N, Li M, Chen H, Hayoun D, et al. The inhibitory receptor PVRIG is dominantly expressed in the bone marrow of patients with multiple myeloma and its blockade enhances T-cell engager’s immune activation. Exp Hematol. 2025;143:104696.[DOI]

-

136. Hudson WH, Gensheimer J, Hashimoto M, Wieland A, Valanparambil RM, Li P, et al. Proliferating transitory T cells with an effector-like transcriptional signature emerge from PD-1+ stem-like CD8+ T cells during chronic infection. Immunity. 2019;51(6):1043-1058.[DOI]

-

137. Li Y, Zhang Y, Cao G, Zheng X, Sun C, Wei H, et al. Blockade of checkpoint receptor PVRIG unleashes anti-tumor immunity of NK cells in murine and human solid tumors. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14(1):100.[DOI]

-

138. Bunet R, Nayrac M, Ramani H, Sylla M, Durand M, Chartrand-Lefebvre C, et al. Loss of CD96 expression as a marker of HIV-specific CD8+ T-cell differentiation and dysfunction. Front Immunol. 2021;12:673061.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite