Yong Qin, MIIT Key Laboratory of Complex-field Intelligent Exploration, Beijing Institute of Technology, Beijing 100081, China. E-mail: qinyong@lzu.edu.cn

Rong Shen, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730000, Gansu, China. E-mail: shenr@lzu.edu.cn

Abstract

Immunotherapy has emerged as a transformative approach in cancer therapeutics, yet its clinical translation remains constrained by significant challenges, including tumor immune evasion mechanisms and suboptimal efficacy of monotherapy, collectively impeding the full realization of its therapeutic potential. With their unique physicochemical properties, tunable enzyme-mimetic activities, and ability to induce cuproptosis, copper-based nanomaterials provide a new solution to overcome these limitations and have become a research focus in the field of targeted antitumor immunotherapy. This review systematically summarizes the research progress of copper-based nanomaterials in tumor immunotherapy, with a focus on discussing their core antitumor immunological mechanisms. These materials trigger immunogenic cell death by inducing cuproptosis and activate the body’s innate and adaptive immune responses through the release of damage-associated molecular patterns, such as calreticulin, high-mobility group box 1, adenosine triphosphate, and mitochondrial DNA. Meanwhile, they remodel the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment by alleviating tumor hypoxia, scavenging immunosuppressive metabolites, and reducing immunosuppressive cells. On this basis, this review further analyzes the combined therapeutic strategies of copper-based nanomaterials with immune checkpoint blockade, photodynamic therapy, photothermal therapy, sonodynamic therapy, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. It also elaborates on the specific mechanisms by which various combined regimens enhance antitumor efficacy, such as through synergistically amplifying oxidative stress, strengthening cell death effects, or improving therapeutic targeting. Additionally, this review discusses the current challenges faced by copper-based nanomaterials in clinical translation and points out future development directions. This review aims to provide a theoretical basis and practical guidance for the clinical translation of multifunctional copper-based nanoplatforms. It also offers new insights for the development of tumor immunotherapies based on metal and redox biology, helping to overcome immune tolerance and improve the efficacy of antitumor treatment.

Keywords

1. Introduction

Immunotherapy represents a pivotal advancement in oncology, harnessing the host immune system to recognize and eliminate malignant cells while offering durable therapeutic responses with favorable safety profiles[1]. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) and adoptive T-Cell therapy (ACT) stand as the two most extensively studied and clinically validated immunotherapeutic modalities, demonstrating remarkable efficacy across diverse malignancies[2]. The ICI ipilimumab has significantly improved overall survival in metastatic melanoma, whereas ACT employing chimeric antigen receptor–modified T cells has achieved potent antitumor responses in relapsed B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia[3,4].

Despite these advances, immunotherapy encounters significant clinical limitations. Tumors exhibiting a “cold” tumor microenvironment (TME), including pancreatic cancer, glioblastoma, and ovarian cancer, feature insufficient immune cell infiltration and elevated immunosuppressive components that critically compromise therapeutic efficacy[5]. Tumor cells further evade immune surveillance through mechanisms such as metabolic reprogramming and aberrant tumor antigen expression[6]. Critically, monotherapy frequently culminates in treatment resistance and disease recurrence, driven by tumor heterogeneity and interpatient variability, underscoring the urgent need for multimodal synergistic strategies[7].

In recent years, copper ions have emerged as particularly promising due to their tunable redox properties and distinctive biological functions. When intracellular copper exceeds physiological levels, it disrupts metabolism and triggers cell death. Excess copper drives Fenton-like reactions, generating reactive oxygen species (ROS)[8]. ROS cause oxidative stress, damage mitochondria, and compromise DNA integrity. This activates apoptosis, pyroptosis, and ferroptosis[9-11]. Critically, it also induces cuproptosis. Cuproptosis is a newly identified form of regulated cell death (RCD) pathways first described by Peter Tsvetkov in 2022[12]. In this pathway, excess Cu2+ is reduced to Cu+ by ferredoxin 1 (FDX1). Cu+ then binds to lipoylated tricarboxylic acid cycle enzymes, including dihydrolipoyl acetyltransferase and dihydrolipoamide succinyltransferase[13]. This binding causes abnormal protein aggregation. It also destabilizes iron-sulfur cluster proteins. The result is proteotoxic stress and cell death. This process induces immunogenic cell death (ICD) and activates antitumor immunity through the release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). Moreover, copper-based nanoplatforms exhibit high drug-loading capacity, structural tunability, and surface modifiability, enabling co-delivery and spatiotemporal controlled release of multiple therapeutic agents[14]. These nanomaterials exhibit multiple enzyme-mimicking activities, including oxidase, peroxidase (POD), catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and glutathione oxidase (GSHOx) functions. These activities enable synergistic modulation of the TME. They alleviate hypoxia, scavenge immunosuppressive metabolites, and reduce immunosuppressive cell populations. As a result, they enhance both innate and adaptive antitumor immune responses[15,16]. Collectively, these properties establish copper-based nanomedicines as multifunctional platforms capable of stimulating immune activation, modulating TME metabolism, and overcoming immune tolerance.

This review systematically explores the antitumor immunotherapeutic mechanisms of copper-based nanomaterials, focusing on their ability to induce ICD, mimic enzymatic activities, and remodel the TME. We further analyze in detail their combinatorial applications with immunotherapy, photodynamic therapy (PDT), photothermal therapy (PTT), sonodynamic therapy (SDT), chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. Key synergistic mechanisms and current challenges in clinical translation are also discussed. Ultimately, this synthesis offers a theoretical foundation and practical roadmap for advancing multifunctional copper-based nanoplatforms toward clinical application.

2. Mechanisms of Antitumor Immunotherapy of Copper-Based Nanomaterials

Copper-based nanoplatforms generally consist of a copper-containing core, a functionalized surface coating, and tumor-targeting ligands. They offer good biocompatibility and precisely tunable physicochemical properties, enabling tailored design for specific therapeutic applications. To date, multiple copper-based nanomaterial architectures have been established for antitumor applications, including copper-copper ionophore complexes, copper-based metal-organic frameworks, membrane-coated biomimetic copper nanoparticles, and copper-organic ligand self-assemblies[17-20]. The primary antitumor mechanism of these nanomedicines involves intracellular copper overload, which triggers cuproptosis. Beyond cuproptosis induction, copper-based nanomaterials function as multi-enzyme-mimetic nanozymes, leveraging the redox cycling capability of copper ions (Cu2+/Cu+) and tunable surface electronic properties to modulate antitumor immunity. Their enzymatic activities, including POD, CAT, and GSHOx, drive key immunomodulatory effects.

POD activity enables Cu2+ to catalyze Fenton-like reactions with H2O2, producing highly reactive hydroxyl radicals (·OH). These radicals cause oxidative damage to macromolecules in tumor cells, intensify intracellular oxidative stress, and promote apoptosis or necrosis. GSHOx activity depletes glutathione (GSH) by reducing Cu2+ to Cu+. This weakens the tumor’s antioxidant capacity. Concurrently, it induces ubiquitination and degradation of glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), which synergistically triggers ferroptosis[11]. CAT activity decomposes H2O2 into O2, alleviating tumor hypoxia. The structural flexibility of copper-based nanoplatforms allows them to function as advanced drug delivery systems. They can efficiently encapsulate or conjugate a variety of therapeutic agents, including short peptides, natural compounds, and small-molecule drugs, enabling precise spatiotemporal co-delivery to tumor sites. This integration facilitates synergistic antitumor strategies combining cuproptosis with complementary cell death pathways. Copper-based nanomaterials integrate enzymatic mimicry with drug delivery to drive multimodal therapeutic effects. They induce cuproptosis and other forms of RCD, triggering ICD and activating antitumor immunity. Importantly, they also reprogram the immunosuppressive TME by alleviating hypoxia, clearing immunosuppressive metabolites, and depleting immunosuppressive cell populations. These actions collectively enhance the effectiveness of immunotherapies.

2.1 Copper-based nanomaterials induce ICD

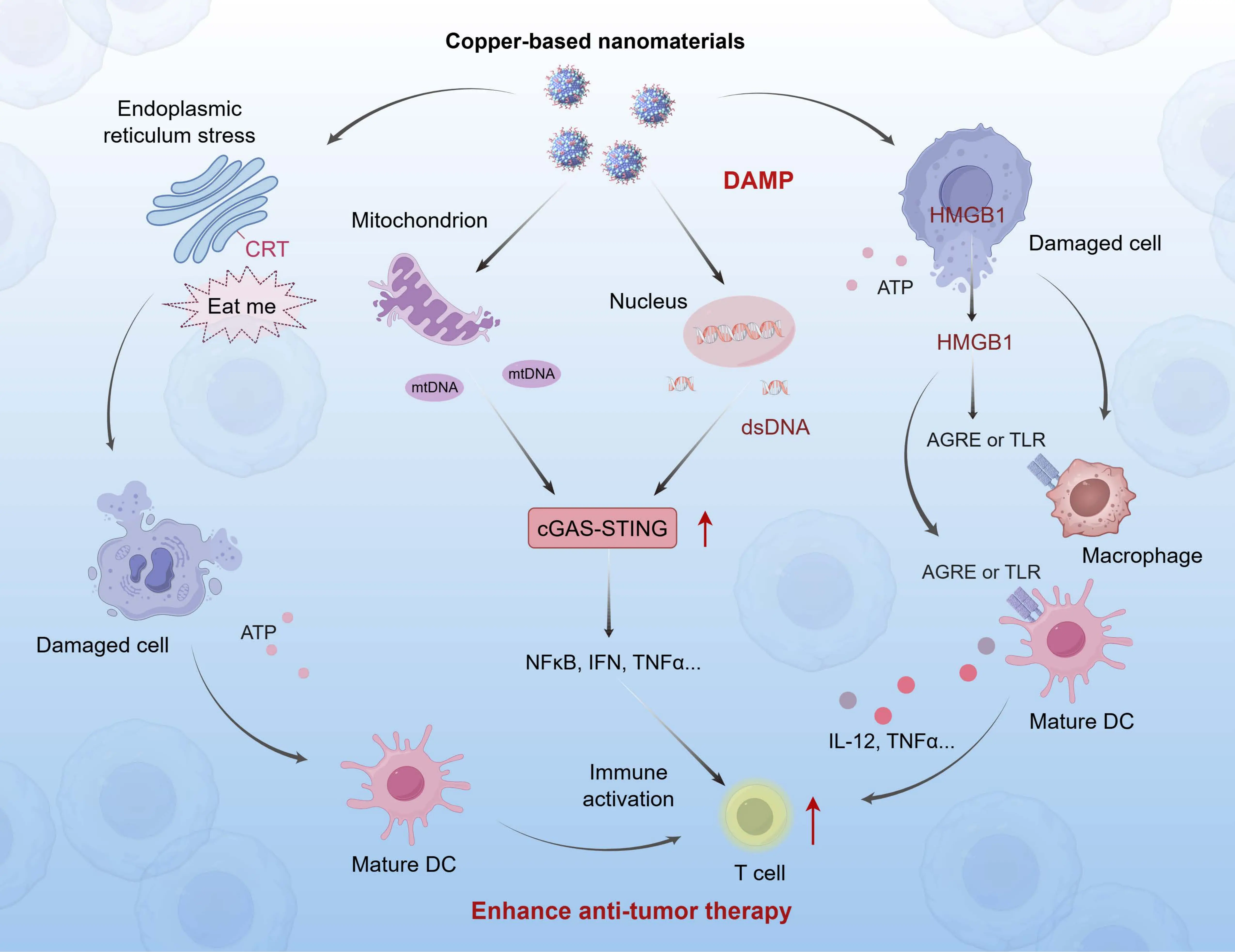

The antitumor immune activation mediated by copper-based nanomedicines fundamentally hinges on the induction of ICD. ICD is characterized by the release or externalization of tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) and DAMPs from dying cells, which function as endogenous danger signals to initiate innate and adaptive immune responses against tumor antigens[21]. Among these DAMPs, calreticulin (CRT), adenosine triphosphate (ATP), high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) serve as defining molecular signatures of ICD. These molecules function as potent endogenous adjuvants that promote the maturation and activation of antigen-presenting cells, especially dendritic cells (DCs), thereby initiating antigen-specific T-cell immune responses[22,23]. Notably, extracellular mtDNA activates the cyclic GMP-AMP synthase-stimulator of interferon genes (cGAS-STING) pathway, leading to the production of type I interferons. This promotes the recruitment of DCs and T cells into the TME, further amplifying systemic antitumor immunity[24,25]. This core mechanism of ICD induction by copper-based nanomaterials, which underlies their combinatorial potential with immunotherapy, is graphically summarized in Figure 1. Copper-based nanomedicines induce ICD through cuproptosis induction or synergistic crosstalk with other RCD pathways, thereby establishing a mechanistic basis for their combinatorial application with immunotherapeutic strategies. This dual induction of cuproptosis and complementary RCD forms orchestrates the release of key DAMPs, culminating in robust activation of tumor-specific adaptive immunity.

Figure 1. Mechanism of ICD induction by copper-based nanomaterials. Copper-based nanomaterials trigger cuproptosis in tumor cells, leading to the release of key DAMPs, including CRT, HMGB, ATP, and mtDNA. These DAMPs facilitate DC maturation, promote antigen-specific T-cell activation, and initiate robust antitumor immune responses within the tumor microenvironment, thereby significantly augmenting therapeutic efficacy. Created in figdraw.com. ICD: immunogenic cell death; DAMPs: damage-associated molecular patterns; CRT: calreticulin; HMGB: high-mobility group box; ATP: adenosine triphosphate; mtDNA: mitochondrial DNA; DC: dendritic cell; AGRE: advanced glycation end-product receptor; TLR: toll-like receptor; IFN: interferon; TNF: tumor necrosis factor; cGAS-STING: cyclic GMP-AMP synthase-stimulator of interferon genes; NFκB: nuclear factor-κB; IL: interleukin.

2.1.1 CRT

CRT, a calcium-binding chaperone resident in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), serves as the pivotal “eat me” signal for copper-based nanomedicine-induced ICD. Copper-based nanomaterials release Cu+/Cu2+ ions, inducing ER stress and autophagy that drive CRT translocation from the ER to the plasma membrane. Intracellular Cu+/Cu2+ generates ROS via Fenton-like reactions, causing ER membrane lipid peroxidation and protein misfolding. This activates the ER stress sensor PERK (EIF2AK3), which phosphorylates eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α, enabling CRT escape from the ER[26]. Concurrently, copper ions regulate autophagy to clear damaged ER structures and maintain ER calcium homeostasis, facilitating ER-to-Golgi anterograde transport of CRT. Membrane-exposed CRT binds to CD91 receptors on DCs, significantly enhancing phagocytosis and cross-presentation of tumor antigens[27]. Luo et al. developed the copper-based nanomodulator ES-Cu-MOF, which releases Cu2+ to trigger ROS-enhanced cuproptosis, induce ICD, and release DAMPs including CRT. In MCA205 murine fibrosarcoma xenograft models, ES-Cu-MOF effectively suppressed tumor growth and prolonged survival[28].

2.1.2 HMGB1

HMGB1, a critical DAMP in copper-based nanomedicine-mediated ICD, functions through AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway regulation. Copper ions induce mitochondrial membrane potential reduction and ATP depletion, directly activating AMPK to bind HMGB1. AMPK phosphorylates HMGB1 at threonine/tyrosine residues, weakening HMGB1-histone H3 interactions and promoting HMGB1 translocation from nucleus to the cytoplasm for extracellular release[29]. During cuproptosis-associated immune activation, extracellular HMGB1 predominantly binds to AGER (RAGE) on macrophages, rather than acting through TLR4-dependent pathways. This interaction activates nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) signaling, induces secretion of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6, and enhances dendritic cell antigen uptake and cross-presentation[30]. Notably, HMGB1’s immunological activity is redox-state dependent: copper-mediated ROS overproduction oxidatively inactivates HMGB1, diminishing immune activation. This explains why mitochondrial ROS scavengers (e.g., MitoQ10) fail to block cuproptosis but impair cuproptosis-induced tumor immunogenicity[31]. Yin et al. developed the nanoassembly TAF-CuET, which co-releases Fe2+/Cu+ to catalyze Fenton-like reactions, deplete GSH, degrade GPX4, and downregulate SLC7A11, inducing ferroptosis. The cuproptosis-ferroptosis crosstalk triggers ICD, releasing DAMPs (including HMGB1) and robustly activating innate/adaptive immunity[32].

2.1.3 ATP

ATP secretion is a crucial mechanism in the induction of ICD during copper-based nanomedicine therapy. This process is driven by the synergistic action of autophagy-lysosomal exocytosis and the activation of pannexin 1 (PANX1) channels. During cuproptosis, copper ions activate Unc-51–like autophagy activating kinase 1/2 through ROS-dependent signaling or direct binding. This activation induces autophagy in multiple cancer types[33,34]. Autophagy facilitates ATP transfer from lysosomes to autolysosomes, while caspase-3–mediated ROCK1 activation induces membrane blebbing to enable lysosomal exocytosis[35]. Concurrently, caspase-3 cleaves the auto-inhibitory C-terminus of PANX1, generating active truncated PANX1 that mediates ATP transmembrane transport[36]. Extracellular ATP binds to P2X7 receptors on DCs, triggering NLRP3 inflammasome activation and subsequent IL-1β release. This enhances the activation and proliferation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL)[37]. Zeng et al. developed the ROS-enhanced prodrug hybrid nanoassembly CA-4S2@ES-Cu, which synergistically generates massive ROS through CA-4 and ES-Cu components. This exacerbates mitochondrial damage and oxidative stress, inducing ICD with ATP release and robust DC maturation. The nanoassembly further promotes natural killer (NK) cell activation, enhances CD4+/CD8+ T-cell infiltration/differentiation within tumors, reduces regulatory T cell (Treg) proportion, and reverses immunosuppressive TMEs[38].

2.1.4 mtDNA

Mitochondrial damage induced by cuproptosis leads to the release of mtDNA, which activates the cGAS-STING pathway. This pathway serves as a critical link between cuproptosis and the activation of adaptive immunity. Copper overload triggers mitochondrial proteotoxic stress and loss of membrane potential, causing cristae disruption and mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization. This enables mtDNA translocation into the cytosol for recognition by cGAS[39]. cGAS dimerizes upon mtDNA binding, utilizing ATP/GTP to synthesize 2',3'-cGAMP, which then activates STING on the ER membrane[40]. Activated STING traffics to the Golgi, recruiting TANK-binding kinase 1 to phosphorylate interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) and NF-κB[41]. Nuclear translocation of phosphorylated IRF3/NF-κB drives transcriptional upregulation of proinflammatory mediators, including type I interferons, IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α, establishing the signaling axis for immune activation[42]. Yan et al. developed an inhalable nanodevice, CLDCu, which synergistically induces cuproptosis via chitosan/Cu2+ release to activate cGAS-STING, robustly enhancing DC maturation, triggering innate/adaptive immunity, and reversing immunosuppressive TMEs[43].

2.2 Copper-based nanomaterials remodel the immunosuppressive TME

2.2.1 Copper-based nanomaterials alleviate tumor hypoxia

Solid tumors often develop hypoxic microenvironments due to rapid proliferation, which drives abnormal angiogenesis and compromises blood perfusion. This leads to insufficient oxygen delivery to meet the high metabolic demands of tumor cells[44]. This hypoxic niche critically promotes immunosuppression and facilitates tumor immune evasion. Under hypoxic conditions, the proliferation of CTLs and their secretion of cytokines such as IFN-γ and TNF-α are markedly suppressed. Concurrently, hypoxia-inducible factor-1α upregulates immune checkpoint molecules such as PD-1 and CTLA-4 on CTLs, promoting T-cell exhaustion[45,46]. Hypoxia also suppresses NK cell cytotoxicity and degranulation, diminishing tumor-killing efficacy[47]. Hypoxic conditions recruit and activate immunosuppressive cells, including Tregs, myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), and M2-type tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs). This further intensifies immunosuppression within the TME[48-50]. Copper-based nanomaterials alleviate tumor hypoxia through multi-enzyme-mimetic activities, drug delivery functions, or synergistic therapeutic effects. This alleviation reverses immunosuppressive phenotypes and enhances antitumor immunity.

TMEs typically exhibit elevated hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) levels, approximately fourfold higher than normal cells[51]. Copper-based nanomaterials exploit CAT activity to decompose H2O2 into O2, effectively alleviating tumor hypoxia and reversing immunosuppressive phenotypes. Li et al. developed the L/D-Cu/Z@MH nanoplatform, in which MnO2 catalyzes H2O2 decomposition to generate oxygen, alleviating tumor hypoxia. The released Mn2+ synergizes with RCD to activate the cGAS–STING pathway. This process enhances cytotoxic T-cell infiltration and overcomes immunosuppression[52]. Additionally, copper-based nanoplatforms incorporating photothermal agents (e.g., CuET@PHF) combine with PTT. Under 808 nm laser irradiation, localized temperature elevation increases vascular permeability and oxygen release, alleviating TME hypoxia. This also reduces collagen deposition and tumor stiffness while upregulating hypoxia-repressed FDX1, amplifying cuproptosis-mediated tumor killing and facilitating immune cell infiltration[53]. Cold exposure (CE) therapy, a non-invasive approach, activates brown adipose tissue (BAT) to generate heat and metabolize glucose, thereby inducing tumor starvation[54]. CE also improves TME hypoxia[55]. Ye et al. integrated CE with a copper single-atom nanozyme, which under 808 nm laser irradiation generates ROS and heat. This induces ICD, releases TAAs for personalized tumor vaccine (TV) preparation, and activates BAT via CE. BAT-mediated glucose consumption suppresses tumor metabolism, while CE simultaneously reduces MDSCs and elevates CD8+ T-cell and memory T-cell proportions, significantly enhancing TV-induced antitumor immunity[56].

2.2.2 Copper-based nanomaterials clear immunosuppressive metabolites

Tumor metabolic reprogramming establishes a profoundly immunosuppressive microenvironment, with lactic acid serving as a key metabolic signature and immunomodulatory signal. Accumulated lactic acid suppresses NK cell cytotoxicity and T-cell activation while promoting MDSC expansion and M2 macrophage polarization[57-59]. Copper-based nanomaterials counteract this by modulating tumor lactic acid metabolism to alleviate immunosuppression. For instance, Zhi et al. developed the Syr@mPDA@CP nanosystem, which incorporates the monocarboxylate transporter 4 inhibitor stirosporine to block lactic acid efflux from tumor cells. The dual effects elevate intracellular lactic acid levels, triggering acidosis-induced dissociation of ferritin heavy chain 1 and iron release. This amplifies ferroptosis while simultaneously reducing extracellular lactic acid in the TME, thereby alleviating immunosuppression. In the 4T1 orthotopic breast cancer model, Syr@mPDA@CP synergistically activated cuproptosis and ferroptosis, significantly inhibiting tumor proliferation and inducing apoptosis. The treatment enhanced dendritic cell maturation, promoted infiltration of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and helper CD4+ T cells, and increased serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-γ) while suppressing immunosuppressive IL-10. This robustly activated both innate and adaptive antitumor immunity[60].

The kynurenine pathway (KP), the primary catabolic route for tryptophan (TRP) metabolism, is critically implicated in immune regulation through its production of immunomodulatory metabolites[61]. KP activation promotes immune tolerance by catalyzing TRP conversion to N-formylkynurenine through indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) and tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase. This process yields immunosuppressive metabolites including kynurenine (KYN) and 3-hydroxykynurenine[62,63]. KP activation depletes TRP while accumulating KYN, impairing T-cell function and promoting Treg differentiation. It also expands MDSCs, collectively suppressing antitumor immunity[64]. Copper-based nanoplatforms counteract KP-mediated immunosuppression by delivering KP inhibitors to block immunosuppressive metabolite production. Myricetin (MY), a natural polyphenol, suppresses IDO1 expression to alleviate T-cell inhibition[65]. Wu et al. engineered the Cu-GM nanoenhancer through self-assembly. Gallic acid inhibits lactate dehydrogenase, suppressing tumor glycolysis and reducing lactic acid production. This dual action synergistically enhances cuproptosis while alleviating immunosuppression in the TME. Concurrently, MY inhibits IDO1 to restore T-cell function. Cuproptosis-triggered ICD releases DAMPs. Combined with KP inhibition, this dual mechanism drives dendritic cell maturation, NK cell activation, and CD8+ T-cell infiltration and differentiation. Collectively, these processes robustly activate antitumor immunity[66].

2.2.3 Copper-based nanomaterials eliminate immunosuppressive cells

Immunosuppressive cells including MDSCs, Tregs, and M2-type TAMs further reinforce the immunosuppressive TME by secreting immunosuppressive cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β. Copper-based nanomaterials counteract this by selectively depleting immunosuppressive cell populations. Xie et al. engineered the copper-doped mesoporous polydopamine (CMP) nanocomposite, which releases Mn2+ to enhance antigen processing and presentation by TAMs and DCs. This facilitates critical co-stimulatory signals for T-cell activation. In multiple murine subcutaneous tumor models (B16-F10 melanoma, Hepa 1-6 hepatocarcinoma, Panc02 pancreatic cancer), CMP treatment increased tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T-cell proportions while upregulating functional genes (Gzmb, Prf1, Nkg7). Concurrently, it reduced Treg infiltration and CTLA-4 expression on Tregs, alleviating immunosuppression. This orchestrated response induced systemic antitumor immunity capable of suppressing distant metastases and establishing long-term immune memory. When combined with anti-PD-L1 antibody, CMP synergistically enhanced tumor suppression while maintaining efficacy after αPD-L1 discontinuation[67]. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), abundantly expressed in the TME, drives angiogenesis and critically suppresses antitumor immunity. It inhibits dendritic cell maturation and antigen presentation, thereby impairing T-cell activation and infiltration into tumors[68]. Additionally, VEGF promotes recruitment and immunosuppressive functions of Tregs, MDSCs, and M2-TAMs[69]. Copper-based nanoplatforms incorporating VEGF pathway inhibitors thus reverse immunosuppression while potentiating copper-induced immunotherapy. Zhang et al. developed the nanotherapeutic M/A@MOF@CM, which delivers axitinib to suppress VEGF signaling. This system reduces Treg, MDSC, and M2-TAM populations, reverses immunosuppression in the TME, and enhances immune responses triggered by ICD induced by apoptosis, ferroptosis, and cuproptosis, significantly improving immunotherapy efficacy[70].

3. Combination Strategies of Antitumor Immunotherapy Using Copper-Based Nanomaterials

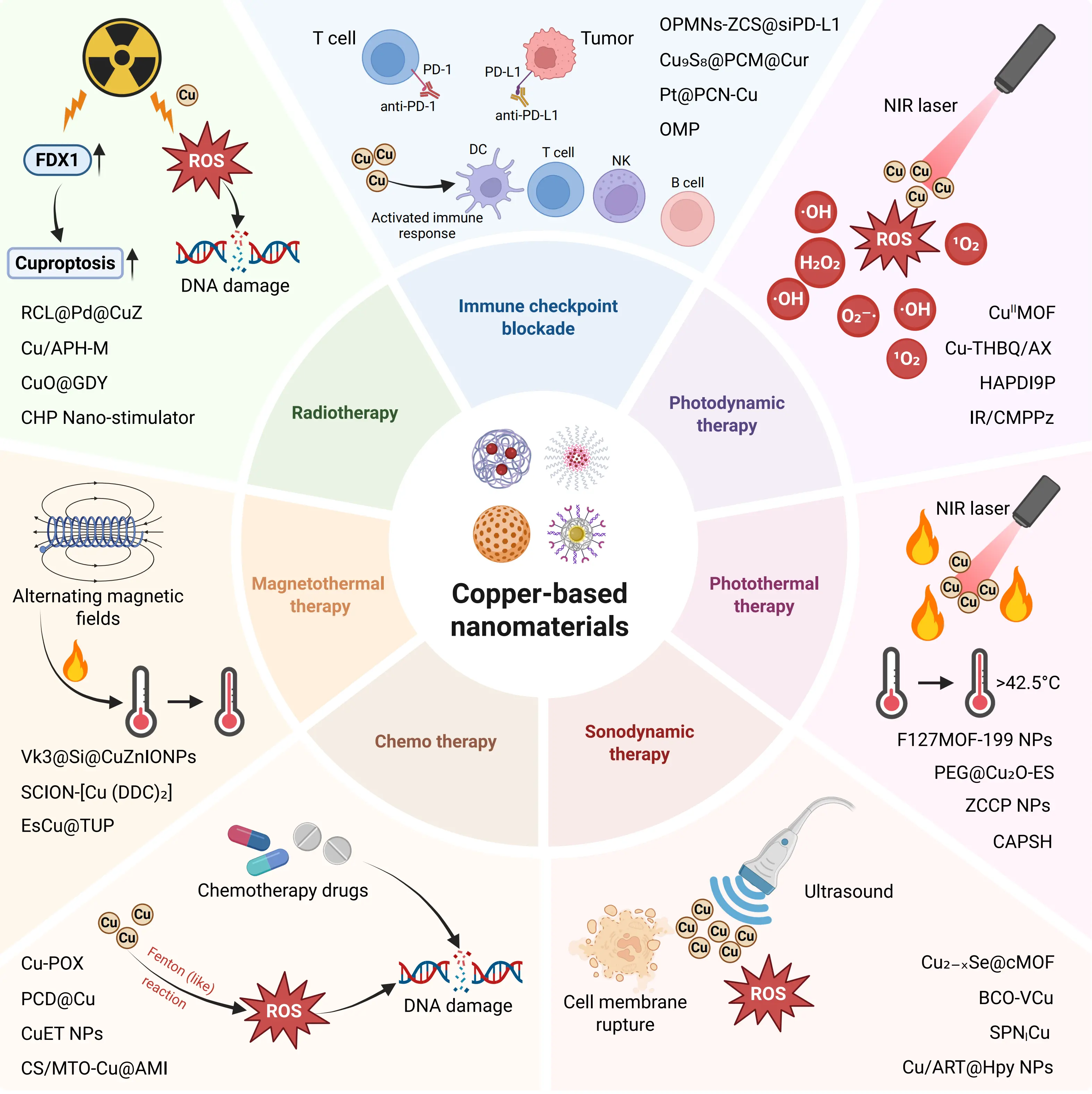

The remarkable immunomodulatory capabilities of copper-based nanomaterials, as detailed in the previous section, provide a solid foundation for their synergistic application with various established therapeutic modalities. As illustrated in Figure 2, these nanomaterials serve as a central platform that integrates diverse physical, chemical, and biological triggers to initiate a convergent antitumor immune response. The following subsections systematically elaborate on the specific mechanisms and outcomes of these powerful combinations, which leverage cuproptosis and ROS bursts to potentiate immunotherapy, remodel the TME, and ultimately achieve enhanced antitumor efficacy.

Figure 2. Schematic illustration of synergistic antitumor immunotherapy mediated by copper-based nanomaterials in combination with various therapeutic modalities. Created in BioRender. DC: dendritic cell; NK: natural killer; MON: monocyte; PD-L1: programmed death-ligand 1; ICB: immune checkpoint blockade; NIR: near-infrared; PDT: photodynamic therapy; PTT: photothermal therapy; SDT: sonodynamic therapy; AMF: alternating magnetic fields; MOF: metal-organic framework; FDX1: ferredoxin 1; ROS: reactive oxygen species; NP: nanoparticle.

3.1 In combination with immunotherapy

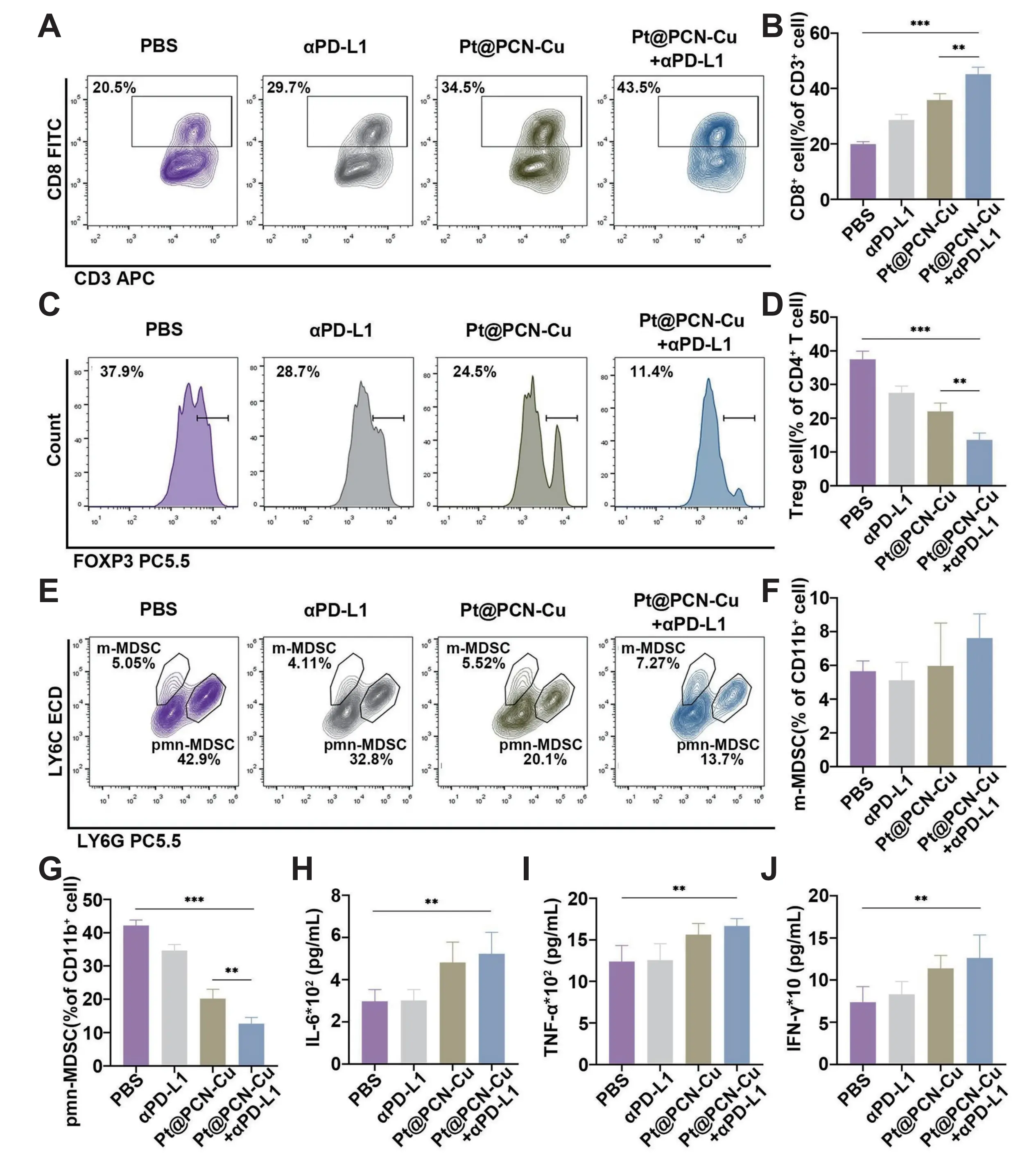

Immunotherapy harnesses the body’s immune system to recognize and eliminate tumor cells, primarily by overcoming tumor immune evasion and activating antitumor immunity. Key modalities include ICIs, ACT, and tumor vaccines[71]. Immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) alleviates T-cell functional inhibition by blocking immunosuppressive pathways (e.g., PD-1/PD-L1, CTLA-4), significantly enhancing tumor cell recognition and killing. However, monotherapy often encounters limitations such as insufficient immune cell infiltration and low tumor immunogenicity[72]. Copper-based nanomaterials overcome these challenges through multi-modal synergies: drug co-delivery upregulates tumor cell PD-L1 expression, sensitizing tumors to anti-PD-L1 therapy[73]. Concurrently, copper-induced ICD releases DAMPs and promotes CD8+ T-cell infiltration, achieving potent synergy with anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy. Yan et al. developed an inhalable nanoplatform OMP, where copper-mediated cuproptosis (enhanced by siPDK targeting pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1) triggers ICD and DAMP release. Simultaneously, it upregulates tumor membrane PD-L1 and soluble PD-L1, significantly amplifying synergy with αPD-L1. In B16F10 lung metastasis models, inhaled OMP significantly suppressed metastatic growth and extended survival, effectively activating adaptive immunity via synergistic cuproptosis induction and PD-L1 blockade without apparent toxicity[74]. Wang et al. engineered Pt@PCN-Cu, which dissociates hexokinase 2 from mitochondria, suppresses glycolytic metabolism, and further elevates PD-L1 expression. Combined with αPD-L1, Pt@PCN-Cu enhances PD-1/PD-L1 blockade and reprograms the TME. As evidenced in Figure 3, this combination therapy significantly inhibits tumor growth, reduces Tregs and PMN-MDSCs, and increases CD8+ T-cell infiltration, thereby significantly improving immunotherapy efficacy. Furthermore, the treatment markedly elevates serum levels of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-γ), confirming enhanced systemic immune activation. This dual mechanism robustly activates innate and adaptive antitumor immunity in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma models[75].

Figure 3. (A, B) Representative flow cytometry plots and corresponding percentages of CD8+ T cells in tumor tissues from mice subjected to various treatments in the combined therapy of Pt@PCN-Cu and αPD-L1; (C, D) Representative flow cytometry plots and corresponding percentages of Tregs in tumor tissues from mice subjected to various treatments; (E-G) Representative flow cytometry plots and corresponding percentages of m-MDSCs and pmn-MDSCs in tumor tissues from mice subjected to various treatments; (H-J) Serum levels of inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α and IFN-γ) measured using ELISAs. Republished with permission from[75]. PD-L1: programmed death-ligand 1; MDSCs: myeloid-derived suppressor cells; IL: interleukin; IFN: interferon; ELISAs: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays; PBS: phosphate buffered saline; PCN: porous coordination network; TNF: tumor necrosis factor; Tregs: regulatory T cells.

Copper-based nanomaterials downregulate tumor cell PD-L1 expression via siRNA or metabolic regulator delivery, weakening PD-1/PD-L1-mediated immunosuppression and synergizing with anti-PD-L1 antibodies. Tao et al. engineered the OPMNs-ZCS@siPD-L1 nanoneedle system, which releases Cu2+/Zn2+ in acidic TME to co-activate the cGAS-STING pathway. Concurrently, siPD-L1 suppresses cuproptosis-induced PD-L1 upregulation, reversing immunosuppression. This dual strategy of “stepping on the gas” (cuproptosis-mediated STING activation and ICD) and “releasing the brake” (PD-L1 knockdown and hypoxia alleviation) proved highly effective in B16F10 melanoma-bearing C57BL/6 mice, achieving a 78.5% tumor inhibition rate and significant suppression of lung metastases through robust innate and adaptive immune activation[76]. Ji et al. developed the photothermally responsive Cu9S8@PCM@Cur nanocomposite. Near-infrared (NIR) light (980 nm) triggers photothermal conversion in hollow Cu9S8 nanoparticles, enabling spatiotemporally controlled curcumin (Cur) release. Cur inhibits EGFR-STAT3 signaling to downregulate tumor cell surface PD-L1, alleviating immune escape. In AKR esophageal cancer-bearing C57BL/6 mice, the nanocomposite exhibited excellent tumor targeting (3.36-fold higher fluorescence intensity than free DiD) and efficient photothermal conversion (> 45 °C under NIR). Monotherapy achieved significant tumor growth inhibition (final tumor volume only 17.1% of control), while combination with anti-PD-1 further enhanced efficacy (tumor weight reduced to 1/18.81 of anti-PD-1 monotherapy) through increased CTL infiltration, reduced Treg proportion, and promoted DC maturation, with no significant systemic toxicity observed[77]. This multimodal PTT-chemotherapy-immunomodulation strategy effectively remodels the TME and enhances antitumor immunity, providing a safe and efficient nanoplatform for combination immunotherapy. The diverse copper-based nanoplatforms developed for synergistic immunotherapy, along with their components and key immunomodulatory outcomes, are systematically summarized in Table 1.

| Nanomaterials | Component | Summary of effects | Refs |

| BSO-CAT@MOF-199@DDM | MOF-199, BSO, CAT, DDM | GSH ↓, O2 ↑, cuproptosis enhancement, DAMPs ↑, mature DCs ↑, CD8+ T cells ↑, TME reversal, synergy with αPD-L1 | [18] |

| OMP | OPDEA, siPDK, Cu MOF | Glycolysis ↓, ATP7B ↓, cuproptosis enhancement, DAMPs ↑, mature DCs ↑, CD8+ T cells ↑, mPD-L1/sPD-L1 ↑, synergy with αPD-L1, TME reversal | [74] |

| Pt@PCN-Cu | PCN-Cu, Pt NPs | Cuproptosis, mitochondrial dysfunction, HK2 dissociation, PD-L1 ↓, synergy with αPD-L1, CD8+ T cells ↑, Tregs ↓, pmn-MDSCs ↓, TAM M1 ↑ | [75] |

| OPMNs-ZCS@siPD-L1 | ZCS NFs, siPD-L1, QCS, PVP, PVA, SPC | Cuproptosis, cGAS/STING activation, PD-L1 ↓, O2 ↑, mature DCs ↑, NK cell ↑, CD4+/CD8+ T cell ↑, memory T cell ↑ | [76] |

| Cu9S8@PCM@Cur | Cu9S8 NPs, PCM, Curcumin | PTT, ROS ↑, DAMPs ↑, PD-L1 ↓, synergy with anti-PD-1, CD8+ T cell ↑, mature DCs ↑, Tregs ↓, TME reversal | [77] |

| CBS | Cu, Bi, Se | PTT, apoptosis, cuproptosis, mature DCs ↑, T cell ↑, synergy with αPD-L1 | [78] |

| NP@ESCu | PHPM, ES, Cu2+ | Cuproptosis, DAMPs ↑, mature DCs ↑, CD8+ T cell ↑, TAM M1 ↑, MDSCs ↓, PD-L1 ↑, synergy with αPD-L1 | [79] |

| ES@CuO | CuO, ES, PEG | Cuproptosis, DAMPs ↑, synergy with αPD-1, CTLs ↑, NK cell ↑, Tregs ↓, TAM M2 ↓, TME reversal | [80] |

| CuP/Er | NCP (Cu2+, peroxides), Erastin, DOPC, cholesterol, DSPE-PEG2K | GSH ↓, cuproptosis sensitization, ferroptosis, DAMPs ↑, mature DCs ↑, PD-L1 ↑, synergy with αPD-L1, CD8+ T cell ↑ | [81] |

| dis-SAzyme-Dox@M | NMOF (Fe3+/Cu2+), Dox, Hepa1-6 cell membrane | Ferroptosis, cuproptosis, DAMPs ↑, M2 macrophage ferroptosis, TAM M1 ↑, mature DCs ↑, CD8+ T cell ↑, Tregs ↓, synergy with αPD-1 | [82] |

| CuSR4M | Cu (OH)2 nanocages, COH-SR4, MB49 cell membrane | AMPK ↑, ATP7A ↓, p53 ↑, ferroptosis enhancement, cuproptosis, PD-L1 ↓, synergy with anti-PD-1, TAM M1 ↑, mature DCs ↑, CD8+ T cell ↑, NK cell ↑ | [83] |

| CACuPDA | DA, Cu2+, Cinnamaldehyde | Mitochondrial impairment, ROS ↑, cuproptosis, ferroptosis, DAMPs ↑, CTLs ↑, Tregs ↓, TME reversal, synergy with anti-PD-L1 | [84] |

| OCT@ES | E. coli BL21 OMVs, ES, Cu2+, Tannic acid | Pyroptosis, cuproptosis, TAA ↑, DAMPs ↑, mature DCs ↑, synergy with αPD-L1, CTLs ↑ | [85] |

| TSF@ES-Cu NPs | TSF NPs, ES-Cu Complex | Cuproptosis, DAMPs ↑, mature DCs ↑, TAM M1 ↑, TME reversal, CD8+ T cell ↑, synergy with αPD-L1 | [86] |

| CGBH NNs | Cu-BTC NNs, Gox, BSO, HA | ROS ↑, pyroptosis, disulfidptosis, DAMPs ↑, inflammatory factor ↑, TME reversal, synergy with anti-PD-L1 | [87] |

| ES@Cu(II)-MOF | Cu(II)-MOF, ES, PEG | ·OH ↑, cuproptosis, DAMPs ↑, synergy with anti-PD-L1, TME reversal, immune enhancement | [88] |

| DSF@CuPDA-PEGM | CuPDA, PEG-Mannose, DSF | In situ Cu(DDC)2 formation, apoptosis, DAMPs ↑, mature DCs ↑, synergy with anti-PD-1 | [89] |

| HPCC | HA-CA Nanomicelles, CuCDs-PPa | PDT, PTT, oxidative stress, HIF-1α ↓, PD-L1 ↓, DAMP ↑, synergy with αPD-L1, CD4+/CD8+ T cell ↑ | [90] |

MOF: metal-organic framework; PCN: porous coordination network; NP: nanoparticle; NF: nanofiber; PCM: phase change material; NMOF: nanoscale metal-organic framework; NN: nanoneedle; OMV: outer membrane vesicles; BSO: buthionine sulfoximine; CAT: catalase; mPD-L1: membrane PD-L1; sPD-L1: soluble PD-L1; Pt: platinum; QCS: quaternized chitosan; PVP: polyvinylpyrrolidone; PVA: polyvinyl alcohol; SPC: soybean phosphatidylcholine; Bi: bismuth; Se: selenium; ES: elesclomol; PEG: polyethylene glycol; Dox: doxorubicin; DA: dopamine; Gox: glucose oxidase; HA: hyaluronic acid; DSF: disulfiram; CuCDs: copper-doped carbon dots; PPa: protoporphyrin IX; HIF: hypoxia-inducible factor; DAMPs: damage-associated molecular patterns; PDT: photodynamic therapy; PTT: photothermal therapy; ·OH: hydroxyl radical; TAA: tumor-associated antigen; ATP: adenosine triphosphate; DCs: dendritic cells; AMPK: AMP-activated protein kinase; CTLs: cytotoxic T lymphocytes; NK: natural killer; Tregs: regulatory T cells; MDSCs: myeloid-derived suppressor cells; TAM: tumor-associated macrophage; HK2: hexokinase 2; ↑: increased; ↓: decreased.

3.2 In combination with PDT

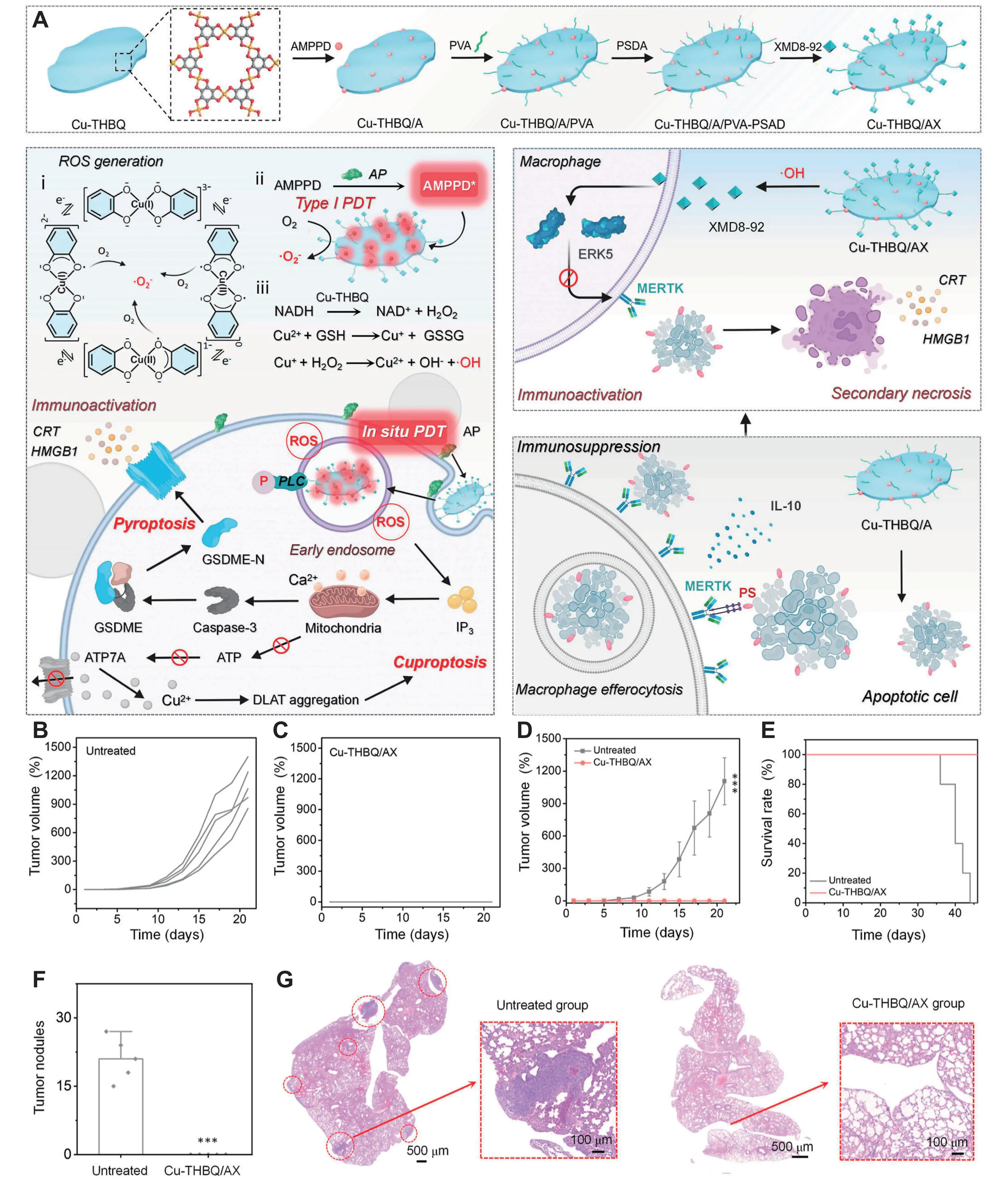

PDT employs light-activated photosensitizers to generate cytotoxic ROS, inducing selective tumor cell damage[91]. Its clinical advantages, including minimally invasive application, spatial precision, and low off-target toxicity, have driven widespread adoption in oncology. Photosensitizers are categorized as Type I or Type II based on distinct photochemical mechanisms[92]. Type I photosensitizers undergo direct electron or hydrogen transfer with substrates upon light activation, producing free radicals (e.g., ·OH, H2O2, O2–·). Type II photosensitizers transfer energy from their triplet excited state to triplet oxygen (3O2), generating singlet oxygen (1O2)[93,94]. Dual-type photosensitizers concurrently initiate both reaction pathways. Copper-based nanomaterials function as effective photosensitizers, generating ROS upon wavelength-specific light absorption. Zhu et al. engineered a copper-based metal-organic framework with orthogonally arranged porphyrin ligands that minimize π-π stacking and ROS self-quenching, enabling efficient 1O2, ·OH, and O2–· generation under light irradiation for potent PDT[95]. This property facilitates the development of multi-drug nanocomposites to amplify antitumor immunotherapy efficacy. Liu et al. designed an in situ therapeutic nanovaccine (Cu-THBQ/AX). Tumor membrane-overexpressed alkaline phosphatase activates the substrate AMPPD to produce chemiluminescence, initiating Type I PDT in Cu-THBQ. Concurrently, Cu-THBQ generates O2–· and ·OH via semiquinone radical catalysis and Fenton-like reactions. ROS accumulation in early endosomes activates phospholipase C, triggering caspase-3-mediated pro-inflammatory pyroptosis. Concurrently, the delivered XMD8-92 inhibitor blocks macrophage efferocytosis, preventing tumor cell phagocytosis by TAMs. This converts the immunosuppressive effects of apoptosis into pro-inflammatory secondary necrosis. This sophisticated cascade, which simultaneously induces pyroptosis, cuproptosis, and secondary necrosis to dramatically enhance tumor immunogenicity, is schematically illustrated in Figure 4A. In the 4T1 breast cancer model, Cu-THBQ/AX elicited robust long-term immune memory, as demonstrated in Figure 4B,C,D,E,F,G, where cured mice showed significant inhibition of tumor growth and lung metastasis upon 4T1 rechallenge[96].

Figure 4. (A) Schematic illustration of activated antitumor immunity after Cu-THBQ/AX treatment by inducing tumor cell pyroptosis, cuproptosis, and secondary necrosis; (B-D) Tumor volume curves; (E) survival curves of tumor-bearing mice rechallenged to 4T1 cells after subcutaneous or intravenous administration of Cu-THBQ/AX; (F) Calculated lung metastasis nodules of the mice after different treatments; (G) H & E-stained lungs or rechallenged tumor-bearing mice after different treatments. Republished with permission from[96]. PVA: polyvinyl alcohol; ROS: reactive oxygen species; AP: alkaline phosphatase; PDT: photodynamic therapy; NADH: nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide hydride; CRT: calreticulin; ERK: extracellular signal-regulated kinases; HMGB: high-mobility group box; PLC: phospholipase C; ATP: adenosine triphosphate; DLAT: dihydrolipoyl acetyltransferase; PS: phosphatidylserine; IL: interleukin; MERTK: C-Mer proto-oncogene tyrosine kinase.

The Type II PDT critically depends on tissue oxygen availability, yet the hypoxic TME severely compromises its efficacy[97]. To overcome this limitation, copper-based nanomaterials integrate nanozymes with multi-enzymatic activity to generate oxygen, alleviating hypoxia and enhancing PDT. Li et al. engineered a copper-based multifunctional platform (HAPDI9P) incorporating Au-Pt nanozymes that exhibit dual enzymatic functions: catalyzing tumor-abundant H2O2 into cytotoxic ROS and O2. This dual action intensifies oxidative stress to amplify cuproptosis while alleviating hypoxia to boost PDT. Under 808 nm NIR irradiation, indocyanine green concurrently executes photodynamic and PTT, further potentiating cuproptosis. In BALB/c mice bearing H22 hepatocellular carcinoma, the HAPDI9P platform combined with NIR irradiation achieved a remarkable 96.9% inhibition of tumor growth, effectively suppressed distant metastasis, and resulted in complete tumor ablation in some subjects[98]. Xu et al. developed a dual-enzyme-mimetic platform (IR/CMPPz), where CMP mimics SOD activity. This catalyzes O2–· conversion to O2 and H2O2, providing substrates for POD activity and the photosensitizer IR780. The resulting cascade generates massive ·OH and 1O2, creating a “ROS storm” that synergistically promotes tumor cell apoptosis and enhances cuproptosis. In 4T1 tumor-bearing mice, this approach, upon NIR irradiation, achieved a significant 82.9% tumor growth inhibition without apparent toxicity to major organs. Furthermore, by activating a systemic immune response, it effectively suppressed lung metastasis[99]. The key design strategies and immunostimulatory outcomes of these and other representative copper-based nanosystems for synergistic PDT are compiled in Table 2.

| Nanomaterials | Component | Summary of effects | Refs |

| CCNAs | ZnPc-TK-DOX, 1-MT, Cu2+ | PDT, apoptosis, cuproptosis, DAMP ↑, mature DCs ↑, IDO inhibition, TME reversal, CTLs ↑ | [20] |

| CuIIMOF | TpyP, Cu2+ | ROS ↑, PDT, ferroptosis, DAMPs ↑, mature DCs ↑, CD8+ T cell ↑, systemic immunity | [95] |

| Cu-THBQ/AX | Cu-THBQ MOF, AMPPD, XMD8-92 | PDT, ROS ↑, pyroptosis, cuproptosis, efferocytosis inhibition, mature DCs ↑, CD4+/CD8+ T cell ↑, TAM M1 ↑, Tregs ↓, immune memory | [96] |

| HAPDI9P | HCuS, Au–Pt Nanozymes, DSF, ICG, 9R–P201 Peptide | PDT/PTT, oxidative stress, cuproptosis enhancement, DAMPs ↑, mature DCs ↑, CTLs ↑, distant metastasis inhibition | [98] |

| IR/CMPPz | CMP, PEOz, IR780 | Multienzyme activities, ROS ↑, Cu2+ efflux inhibition, cuproptosis enhancement, PTT/PDT, DAMPs ↑, mature DCs ↑, CD8+ T cell ↑, Tregs/MDSCs ↓, TME reversal, lung metastasis inhibition | [99] |

| BAu-CuNCs | AuNCs, Cu-HAS, BMVs | ROS ↑, cuproptosis enhancement, mature DCs ↑, CD8+/CD4+ T cell ↑, Tregs ↓, lung metastasis inhibition, TME reversal | [100] |

| AE-Cu-PEG2k-DSPE-FA NPs | Aloe-emodin, Cu2+, PEG2k-DSPE-FA | PDT, ROS ↑, cuproptosis sensitization, ER stress, mature DCs ↑, CD8+ T cell ↑, MDSCs/M2-TAM ↓, synergy with αPD-L1 | [101] |

| TCe6@Cu/TP5 NPs | TPP-Ce6, Cu2+, Thymopentin | PDT, ROS ↑, cuproptosis, AMPK activation, PD-L1 ↓, mDNA ↑, cGAS-STING activation, DCs/T cell ↑, systemic immunity, immune memory | [102] |

| CCS-ICG | Cu2+, CaO2, SiO2 Shell, ICG, PVP-K30 | Calcium overload, PDT/PTT, pyroptosis, cuproptosis enhancement, DAMPs ↑, mature DCs ↑, CD4+/CD8+ T cell ↑ | [103] |

| PGIC NPs | PTX, GOx, Cu2+, ICG | Glucose ↓, PDT/chemotherapy, oxidative stress, cuproptosis enhancement, mature DCs ↑, T lymphocyte activation | [104] |

| CIGP | Cu7S4-In2S3 Heterojunction, GOx, PEG | PTT/PDT, ROS ↑, H2O2 ↑, gluconic acid ↑, ROS ↑, indirect immune activation | [105] |

| Cu-N-CDs@OVA | Cu-N-CDs, OVA | PTT, PDT, SDT, mature DCs ↑, OVA/TAAs ↑, CD8+/CD4+ T cell ↑, synergy with anti-PD-L1, immune memory | [106] |

CuIIMOF: copper-based metal-organic framework; AE: aloe-emodin; PEG: polyethylene glycol; FA: folic acid; NP: nanoparticle; TP: thymopentin; CCS: copper-calcium peroxide-silica; ICG: indocyanine green; HCuS: hydrogenated copper sulfide; Pt: platinum; DSF: disulfiram; CMP: copper-doped mesoporous polydopamine; HAS: hyaluronic acids; BMV: bacterial membrane vesicle; TPP: triphenylphosphonium; PVP: polyvinylpyrrolidone; PTX: paclitaxel; GOx: glucose oxidase; OVA: ovalbumin; DAMPs: damage-associated molecular patterns; PDT: photodynamic therapy; PTT: photothermal therapy; SDT: sonodynamic therapy; TAA: tumor-associated antigen; ER: endoplasmic reticulum; AMPK: AMP-activated protein kinase; CTLs: cytotoxic T lymphocytes; Tregs: regulatory T cells; MDSCs: myeloid-derived suppressor cells; TAM: tumor-associated macrophage; IDO: indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase; DOX: doxorubicin; ↑: increased; ↓: decreased.

3.3 In combination with PTT

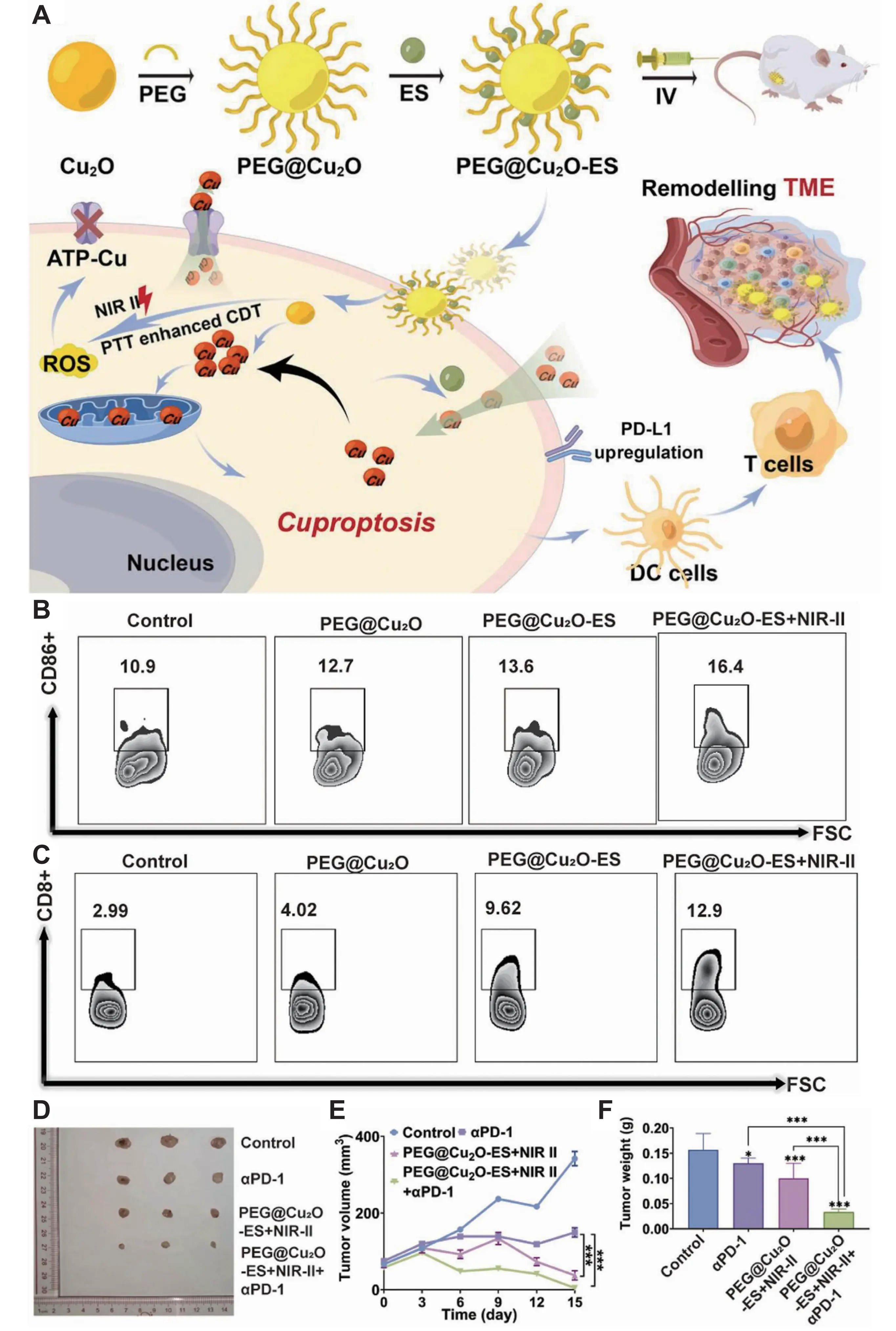

PTT employs photothermal agents that convert NIR light into heat, elevating local temperature to cytotoxic thresholds (> 42.5 °C) for selective tumor ablation[107]. PTT-induced hyperthermia enhances tumor vascular permeability and blood flow, facilitating nanodrug accumulation[108]. Concurrently, thermal stress upregulates heat shock proteins and recruits NK cells, amplifying antitumor immunity[109,110]. Copper-based nanomaterials (e.g., CuO, CuS, copper-doped quantum dots) exhibit superior photothermal conversion efficiency[111]. Integrating PTT into copper-based nanodrug systems enables targeted temperature elevation under NIR irradiation, enhancing oxidative stress induction and tumor immune activation for synergistic antitumor effects. Guan et al. engineered a multifunctional copper platform (CAPSH). Under 1064 nm NIR-II laser irradiation, Cu9S8 generates localized hyperthermia to kill tumor cells and decomposes AIPH to produce oxygen-independent alkyl radicals, further augmenting cytotoxicity. Synergistic induction of cuproptosis, PTT, and radical-mediated killing triggers ICD, releasing DAMPs. This cascade promotes DC maturation, increases CD8+ T-cell infiltration, and elevates pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IFN-γ) in the TME. In both subcutaneous and orthotopic 4T1 breast cancer models, CAPSH demonstrated precise tumor targeting under NIR-II irradiation, which translated into significant suppression of primary tumor growth, reduction of lung metastases, and improved long-term survival rates, without inducing apparent toxicity to major organs[112]. Li et al. developed a PTT-enhanced nanocomposite (PEG@Cu2O-ES). NIR-II irradiation activates Cu2O to drive photothermal-enhanced Fenton-like reactions, generating abundant ROS that potentiate cuproptosis. This triggers ICD and upregulates tumor cell PD-L1 expression. In 4T1 breast cancer xenografts, PEG@Cu2O-ES combined with NIR-II and αPD-1 therapy significantly enhanced DC maturation, CD8+ T-cell infiltration, and tumor suppression, without systemic toxicity[113]. These key findings, encompassing the proposed mechanism, the resultant immune activation, and therapeutic efficacy, are comprehensively depicted in Figure 5.

Figure 5. (A) Schematic illustration of remodeling TME by inducing cuproptosis with PEG@Cu2O-ES NPs to enhance the effectiveness of immunotherapy in breast cancer; (B-C) Flow cytometry analysis of CD86+ DC cells (B) and CD8+/CD4+ T cells (C) in tumors extracted mice treated with various NPs; (D) The photograph of tumors extracted from mice with various treatment at 15 days, when the mice were euthanized; (E-F) Tumor-growth curves (E) and tumor weight (F) of 4T1-bearing mice. Republished with permission from[113]. NPs: nanoparticles; DC: dendritic cell; PEG: polyethylene glycol; ES: elesclomol; ATP: adenosine triphosphate; TME: tumor microenvironment; ROS: reactive oxygen species; NIR: near-infrared; PTT: photothermal therapy; CDT: catalytic degradation therapy; PD-L1: programmed death-ligand 1; FSC: forward scatter.

To achieve precise PTT targeting tumors, Xiao et al. engineered GSH/H2S dual-responsive nanoparticles (F127MOF-199 NPs). In colorectal cancer (CRC) microenvironments with elevated H2S, these nanoparticles undergo in situ sulfidation to generate Cu2-xS nanomaterials. Under NIR-II laser irradiation, Cu2-xS simultaneously mediates PTT and catalytic degradation therapy. The combined photothermal effect and ·OH radicals activate caspase-3, cleaving GSDME (highly expressed in CRC) to induce pyroptosis. In CT26 CRC-bearing mice, F127MOF-199 NPs plus NIR-II laser significantly promoted DC maturation in tumor-draining lymph nodes and spleen, enhanced CD8+ T-cell activation in spleen and tumor infiltration, reversed “cold” to “hot” tumor phenotypes, suppressed tumor growth, and extended mouse survival[114]. Beyond the intrinsic PTT capability of copper-based materials, ligands with photothermal activity can be incorporated to synergize with copper nanomaterials. Chen et al. synthesized a Zn-Co-Cu MOF functionalized with TMPyP as a ligand. Upon NIR excitation, TMPyP converts to phlorin, generating localized heat for PTT. Elevated ROS levels and temperature jointly activate NLRP3 inflammasome and caspase-1, triggering pyroptosis and cuproptosis while amplifying antitumor immunity. In 4T1 breast cancer models, ZCCP NPs combined with NIR irradiation achieved a remarkable tumor inhibition rate exceeding 90%, demonstrating excellent biosafety with no apparent toxicity to major organs[115]. The expanding repertoire of photothermal agents and combinatorial mechanisms employed in copper-based nanoplatforms is categorized in Table 3.

| Nanomaterials | Component | Summary of effects | Refs |

| CAPSH | Cu9S8 NPs, AIPH, PAH, siATP7A, HA | PTT, Cu2+ efflux inhibition, cuproptosis enhancement, DAMPs/TAAs ↑, mature DCs ↑, CD4+/CD8+ T cell ↑, systemic immunity | [112] |

| PEG@Cu2O-ES | Cu2O, ES, PEG | PTT, ROS ↑, ATP-Cu pump disruption, cuproptosis enhancement, DCs/CD8+ T cell ↑, PD-L1 ↑, synergy with αPD-1 | [113] |

| F127MOF-199 NPs | MOF-199, Pluronic F127 | In situ sulfidation to Cu2-xS, PTT/CDT, caspase-3 ↑, GSDME ↓, pyroptosis, cuproptosis, DAMPs ↑, mature BMDCs ↑, CD8+ T cell ↑ | [114] |

| ZCCP NPs | Zn-Co-Cu MOF, TMPyP | ROS ↑, PTT, NLRP3/caspase-1 ↑, GSDMD ↓, pyroptosis, cuproptosis, DAMPs ↑ | [115] |

| MACuS | Cu2-xS, Glucose-6-Phosphate | PTT, cuproptosis, DAMPs ↑, mature DCs ↑, TAM M1 ↑, CD8+ T cell ↑, effector Tem ↑ | [116] |

| CTMF NPs | CuS, PFCE, DA-Polymer, Mn2+-TA Shell | PTT, cuproptosis, DAMPs ↑, mature DCs ↑, CD4+/CD8+ T cell ↑ | [117] |

| CuMoO₄ Nanodots | Cu2+, Mo6+, SDS | PTT, oxidative stress, cuproptosis | [118] |

| CuX-P | DSF, Cu2+, MXene, CTLL2-PD-1 Membrane | PTT, cuproptosis, mature DCs ↑, CD8+ T cell ↑, Tregs/MDSCs ↑, immune memory | [119] |

| CPI NBs | CuCl2, Na2HAsO4, DSF, TPP⁺ | PTT, As3+ ↑, cuproptosis, DAMPs ↑, mature DCs ↑, CD4+/CD8+ T cell ↑, TME reversal | [120] |

| CEL NP | Cu2-xS HNSs, ES, LA | PTT, mitochondrial damage, cuproptosis, DAMPs ↑, mature DCs ↑, CD4+/CD8+ T cell ↑, TME reversal | [121] |

| CuNTD | Ti3C2 Nanosheets, Cu+, DSPE-PEG2000 | PTT, ROS ↑, cuproptosis/ferroptosis enhancement, DAMPs ↑, mature DCs ↑, DCs migration to LNs, CD4+/CD8+ T cell ↑, immune memory | [122] |

| Pt/Cu DAzyme | Mesoporous Carbon, Pt, Cu, PVP | GSH ↓, cuproptosis enhancement, PTT, ROS ↑, DAMPs ↑, mature DCs ↑, synergy with αPD-L1, TME reversal | [123] |

| CuM@RR | MOF-199, DSPE-PEG2000-RGD, RMVs | Cuproptosis, PTT, apoptosis, mitochondrial damage, DAMPs/TAAs ↑, mature DCs ↑, CTLs ↑ | [124] |

| DSF/IONC@Au/MSN-TA NPs | IONC, Au nanodots, MSN, DSF, TA | Glucose ↓, GSH ↓, cuproptosis/ferroptosis sensitization, DAMPs ↑, cGAS-STING activation, mature DCs ↑, CTLs ↑, systemic immunity | [125] |

NP: nanoparticle; PEG: polyethylene glycol; Pt: platinum; PAH: poly(allylamine hydrochloride); HA: hyaluronic acid; ES: elesclomol; MOF: metal-organic framework; DA: dopamine; SDS: sodium dodecyl sulfate; LA: lipoic acid; PVP: polyvinylpyrrolidone; IONC: iron oxide nanocube; TA: tannic acid; RMVs: red blood cell membrane vesicles; PTT: photothermal therapy; DAMPs: damage-associated molecular patterns; TAA: tumor-associated antigen; DCs: dendritic cells; ROS: reactive oxygen species; GSH: glutathione; ATP: adenosine triphosphate; cGAS-STING: cyclic GMP-AMP synthase-stimulator of interferon genes; CTLs: cytotoxic T lymphocytes; Tregs: regulatory T cells; MDSCs: myeloid-derived suppressor cells; TAM: tumor-associated macrophage; CDT: catalytic degradation therapy; ↑: increased; ↓: decreased.

3.4 In combination with SDT

SDT employs ultrasound (US) irradiation to activate sonosensitizers, promoting their transition from ground to excited states. Upon electron relaxation, substantial energy release triggers reactions with surrounding oxygen molecules, generating ROS[126]. Consequently, SDT primarily induces tumor cell death through cavitation effects and ROS-mediated cytotoxicity[127]. Compared to phototherapy, SDT offers superior tissue penetration depth, absence of phototoxicity, and reduced side effects[128]. Copper-based nanodrugs demonstrate promising potential as sonosensitizers, with both inorganic and organic variants enabling targeted delivery and synergistic therapy via copper-based nano-platforms. This expands the therapeutic scope of copper-based nanomaterials in SDT applications.

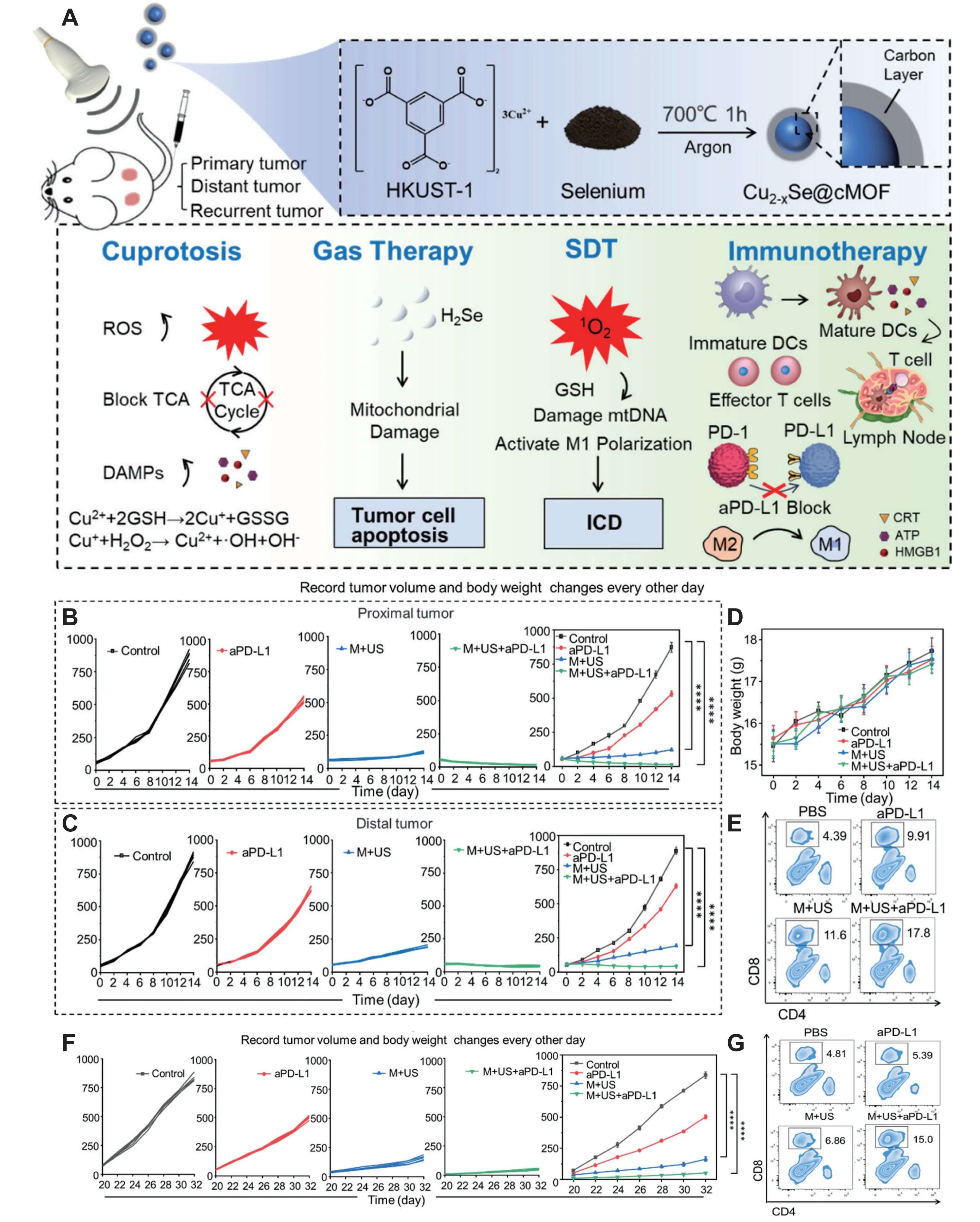

Zhao et al. engineered a multifunctional nanoplatform (Cu2-xSe@cMOF) integrating SDT, cuproptosis induction, and gas therapy. Selenide ions generate H2Se gas under physiological conditions, inducing cellular damage. US irradiation activates the platform to produce ROS, which disrupt mitochondrial membranes via SDT while synergistically amplifying cuproptosis-induced proteotoxic stress. The design of this trimodal therapeutic nanoplatform and its proposed mechanism of action are schematically depicted in Figure 6A. In the 4T1 breast cancer model, Cu2-xSe@cMOF combined with US and αPD-L1 therapy significantly suppressed primary tumor growth, prevented distant metastasis, reduced tumor recurrence, and exhibited no major organ toxicity in mice. As validated in Figure 6B,C,D,E,F,G, the treatment elicited a potent antitumor response, characterized by inhibited tumor growth in both proximal and distal sites, alongside a significant increase in tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells[129].

Figure 6. (A) Schematic of trimodal tumor therapy and immunotherapy using Cu2–xSe@cMOF nanoparticles; Tumor growth of the (B) proximal tumor and (C) distal tumor in the bilateral tumor model over 14 days after different treatments; (D) Body weights of mice after various treatments; (E) Flow cytometric analysis of CD8+ T cells (CD45+CD3+CD8+) in distal tumor samples obtained from mice; (F) Changes in tumor volume after combination of Cu2-x Se@cMOF and a PD-L1 therapy in the subcutaneous 4T1 tumor recurrence model; (G) Flow cytometric of CD8+ T cells (CD45+CD3+CD8+) in tumor samples obtained from mice. Reprinted with the permission from[129]. MOF: metal-organic framework; ROS: reactive oxygen species; TCA: tricarboxylic acid; DAMPs: damage-associated molecular patterns; GSH: glutathione; mtDNA: mitochondrial DNA; ICD: immunogenic cell death; PD-L1: programmed death-ligand 1; SDT: sonodynamic therapy; CRT: calreticulin; HMGB: high-mobility group box; ATP: adenosine triphosphate.

Du et al. developed barium calcium oxide (BCO)-VCu nanoparticles, where US excitation induces ferroelectric polarization in BCO, triggering band bending. Concurrently, V_Cu sites suppress electron-hole recombination, markedly enhancing catalytic ROS generation. This cascade disrupts mitochondrial membrane potential, induces extracellular Ca2+ influx, and activates the Bax/Bcl-2 apoptotic pathway to drive tumor cell death. The ferroelectric charge of BCO-VCu acts as a tunable mechanism: it enhances tumor cell membrane permeability to promote nanoparticle endocytosis while downregulating copper transporters ATP7A and ATP7B. This inhibits Cu+ efflux, elevates intracellular copper accumulation, and triggers proteotoxic stress leading to cuproptosis. Additionally, BCO-VCu alleviates TME hypoxia via its ferroelectric effect, facilitating immune cell infiltration. In 4T1 tumor-bearing and bilateral tumor models, intravenously administered BCO-VCu efficiently accumulated at tumor sites via the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, peaking at 8 hours. When combined with ultrasound, it elicited a profound antitumor response, reducing primary tumor volume by over 80% and significantly inhibiting distal tumor growth. Immune profiling revealed an 8-fold increase in tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells, elevated serum levels of TNF-α and IFN-γ, and induction of memory T cells, collectively contributing to sustained tumor suppression and recurrence prevention[130].

Yu et al. engineered a sono-controlled cascaded lactate-depleting nanoreactor (SPN1Cu). Under US irradiation, the semiconductor polymer PFODBT generates 1O2, which synergizes with cuproptosis to activate ICD and release DAMPs. Concurrently, lactate oxidase depletes TME lactate, alleviating immunosuppression and preserving immune effector cell function. The deep tissue penetration of US enables SPN1Cu to target deep-seated pancreatic tumors, overcoming the penetration limitations of photo-controlled therapies. In Panc02-derived pancreatic cancer models, ultrasound-activated SPN1Cu significantly reduced tumor volume, inhibited metastasis, prolonged mouse survival, and enhanced dendritic cell maturation and immune effector cell infiltration within the TME. This effectively activated both innate and adaptive antitumor immunity[131]. Li et al. developed hybrid nanoparticles (Cu/ART@Hpy). Under US irradiation, the sonosensitizer artesunate (ART) cleaves its peroxide bridge to generate ROS, depletes intracellular GSH, and promotes mitochondrial accumulation of Cu2+, potentiating cuproptosis. In 4T1 breast cancer models, the combination of Cu/ART@Hpy with ultrasound resulted in significant tumor growth inhibition and reduced metastatic risk, without inducing apparent toxicity to major organs[132]. A comprehensive overview of these and other innovative copper-based nanosystems developed for SDT is provided in Table 4, highlighting the representative paradigms in this emerging field.

| Nanomaterials | Component | Summary of effects | Refs |

| Cu2-xe@cMOF | cMOF, Cu2-xSe | SDT, ROS ↑, cuproptosis enhancement, DAMPs ↑, mature DCs ↑, CD8+ T cell ↑, synergy with αPD-L1, Tregs/MDSCs ↑, TAM M1 ↑, TME reversal | [129] |

| BCO-VCu | Bi (NO3)4, Cu (NO3)2, PEG | Ultrasound-triggered ferroelectric catalysis, ROS ↑, apoptosis, cuproptosis enhancement, DAMPs ↑, NF-κB pathway activation, TAM M1 ↑, mature DCs ↑, CD8+ T cell ↑, memory T cell ↑ | [130] |

| SPNICu | PFODBT, LOx, Cu2+, DSPE-PEG-TK, DSPE-PEG-PA | SDT, lactate ↓, TME reversal, cuproptosis, DAMPs ↑, mature DCs ↑, immune effector cell ↑ | [131] |

| Cu/ART@Hpy NPs | SiO2-NH2, Cu2+, ART, POPs | SDT, ROS ↑, GSH ↓, mitochondrial Cu2+ ↑, cuproptosis enhancement, apoptosis, DAMPs ↑, mature DCs ↑, TAM M1 ↑, CD4+/CD8+ T cell ↑, Tregs/MDSCs ↓, TME reversal | [132] |

| ZCA NSs | Zn2+, Cu2+, Al3+ | SDT, cuproptosis, DAMPs ↑, mature DCs ↑, CTLs ↑, metastasis inhibition | [133] |

| RC NPs | Poly RA, Poly MPN, Cu2+ | SDT, ROS ↑, cuproptosis enhancement, DAMPs ↑, mature DCs ↑, TAM M1 ↑, CD8+ T cell ↑, Tregs ↓, TME reversal | [134] |

| CWO NPs | CuWO4 | SDT, ·OH ↑, cuproptosis/ferroptosis, mitochondrial damage, DAMPs ↑, mature DCs ↑, CD4+/CD8+ T cell ↑ | [135] |

| GQD/Cu2-xSe | Cu2-xSe, CTL | SDT, ROS ↑, cuproptosis enhancement, topoisomerase I/II inhibition, DNA damage, mature DCs ↑, CD8+ T cell ↑ | [136] |

| CMC | Cu-MOF | SDT, ROS ↑, cuproptosis, CDT, DAMPs ↑, mature DCs ↑, CD4+/CD8+ T cell ↑, Tregs ↓, metastasis inhibition | [137] |

| CRUPPA19 | UiO-66-NH2, Rhein, mPEG-PO3, Anti-CD19 Antibody | SDT, ROS ↑, cuproptosis/apoptosis, m6A demethylase inhibition, PD-L1 mRNA ↓, DAMPs ↑, mature DCs ↑, CD8+ T cell ↑, primary lymphoma/bone marrow inhibition | [138] |

| Cu2O/Ti3C2Tx Heterojunction | Cu2O Nanocubes, Ti3C2Tx (MXene) Nanosheets | ·OH ↑, cuproptosis, SDT, CDT, DAMPs ↑, mature DCs ↑, CD4+/CD8+ T cell ↑, distant tumor inhibition | [139] |

| GQD/Cu2O Heterojunction | Cu2O Nanocubes, GQDs | SDT, 1O2/O2–· ↑, cuproptosis enhancement, topoisomerase I/II inhibition, DNA damage, DAMPs ↑, mature DCs ↑, CD4+/CD8+ T cell ↑, TME reversal, distant tumor suppression, long-term immune memory | [140] |

MOF: metal-organic framework; SDT: sonodynamic therapy; ROS: reactive oxygen species; DAMPs: damage-associated molecular patterns; MDSCs: myeloid-derived suppressor cells; TAM: tumor-associated macrophage; PEG: polyethylene glycol; NF-κB: nuclear factor-κB; DCs: dendritic cells; GSH: glutathione; CTL: cytotoxic T lymphocyte; GQD: graphene quantum dot; PD-L1: programmed death-ligand 1; mRNA: messenger RNA; CDT: catalytic degradation therapy; Tregs: regulatory T cells; BCO: barium calcium oxide; LOx: lactate oxidase; ART: artesunate; ↑: increased; ↓: decreased.

3.5 In combination with chemotherapy

Chemotherapy suppresses tumor growth through apoptosis induction and DNA cross-linking using agents such as doxorubicin (DOX), cisplatin (CDDP), and mitoxantrone (MTO), remaining a cornerstone of non-surgical cancer therapy[141]. However, conventional regimens often require high-dose, prolonged administration, leading to drug resistance and adverse effects[142]. Copper-based nanodrugs overcome these limitations by enabling targeted drug delivery, enhancing cellular uptake, providing controlled release kinetics, and facilitating synergistic multi-drug combinations. This approach improves therapeutic efficacy while reducing dosing requirements. The representative copper-based nanoplatforms designed to achieve these goals, along with their components and mechanisms of action, are presented in Table 5, which provides a conceptual overview of this section. Following this framework, several paradigmatic examples are discussed in detail below. Zhang et al. engineered a self-assembled nanocomposite Cu-POX. DOX directly induces apoptosis while upregulating nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase 4, sustaining H2O2 production to maintain Fenton-like reactions and amplify Cu+-mediated oxidative stress. Concurrent GSH depletion triggers ferroptosis, synergizing with cuproptosis and apoptosis to enhance tumor cell killing[143]. Wang et al. developed copper-based composite nanoparticles PCD@Cu. DOX and camptothecin. These induce apoptosis via DNA damage, and their combination with cuproptosis synergistically activates ICD and the cGAS/STING pathway. This triggers type I interferon release, promoting DC maturation, NK cell activation, and CD8+ T-cell infiltration and differentiation, thereby remodeling the immunosuppressive TME. In orthotopic 4T1 triple-negative breast cancer models, PCD@Cu effectively activated both innate and adaptive immunity, significantly suppressed tumor growth, and demonstrated no major organ toxicity, confirming excellent biocompatibility[144].

| Nanomaterials | Component | Summary of effects | Refs |

| M/A@MOF@CM | Cu-BTC MOF, MTO, AXB, 4T1 Tumor Cell Membrane | AXB/VEGF inhibition, TME reversal, Tregs/M2-TAM ↓, PTT, ROS ↑, mature DCs ↑, CD8+ T cell ↑ | [70] |

| Cu-POX | Cu2+, DOX, PDA | ·OH ↑, H2O2 ↑, GSH ↓, GPX4 ↓, ferroptosis, apoptosis, DAMPs ↓, mature DCs ↑, CD8+ T cell ↑, synergy with αPD-L1, primary/abscopal tumor inhibition, immune memory | [143] |

| PCD@Cu | Cu2+, PEG-TK-DOX, PEG-DTPA-SS-CPT | Apoptosis, cuproptosis, DAMPs ↑, cGAS/STING activation, type I IFN ↑, mature DCs ↑, CD8+ T cell ↑, CTLs ↑, Tregs ↓, TME reversal | [144] |

| CuET NPs | CuET, BSA | Cuproptosis, DAMPs ↑, innate immune activation, DNA double-strand breaks | [149] |

| CS/MTO-Cu@AMI | MTO-Cu, amiloride, CS | Cuproptosis, AMPK/PD-L1 ↓, ROS ↑, symbiont inactivation, mitochondrial metabolic disorder, macropinocytosis/exosome secretion inhibition, M2-TAM ↓, dsDNA damage, cGAS-STING activation, mature DCs ↑, CD8+ T cell ↑, Tregs ↓ | [151] |

| M/CuO2/DOX | CuO2, DOX, Mouse Macrophage Cell Membrane, PSBMA Hydrogel, 2'3'-cGAMP | cuproptosis, DAMPs ↑, cGAS-STING activation, mature DCs ↑, CD8+ T cell ↑, post-surgical recurrence/metastasis inhibition | [152] |

| cDOX-CP@Bicelle | DPPC, DHPC, CP, cDOX | GSH ↓, oxidative stress, cuproptosis enhancement, DAMPs ↑, mature DCs ↑, CD8+ T cell ↑ | [153] |

| Azido-HA@Cu2O@DNA | Azido-HA, Cu2O, CRISPR/Cas9 Plasmid (sgCD47), DBCO-DOX | CD47 knockdown, macrophage phagocytosis enhancement, cuproptosis, T cell ↑ | [154] |

| GPCuD NPs | PEG5-G7-PTyrOH, Cu2+, DOX-PBA | ROS ↑, cuproptosis, DAMPs ↑, mature DCs ↑, CD8+ T cell ↑, IFN-γ+CD8+ CTL ↑, M2-TAM/Tregs/MDSCs ↓, functional memory T cell ↑ | [155] |

| PCD@CM | Pdots, Cu2+, DOX, 4T1 Tumor Cell Membrane | PTT, cuproptosis enhancement, DAMPs ↑, mature DCs ↑, synergy with αPD-L1, CD8+ T cell ↑, Tregs ↓, metastasis/distant tumor inhibition | [156] |

| CGDMRR | CCp, Gox, Dox, 1-Methyltryptophan, Red Blood Cell Membrane | O2 ↑, glucose ↓, DAMPs ↑, mature DCs ↑, T cell ↑, IDO pathway inhibition, Tregs ↓, synergy with anti-PD-L1, systemic immunity | [157] |

MOF: metal-organic framework; MTO: mitoxantrone; AXB: axitinib; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; TME: tumor microenvironment; TAM: tumor-associated macrophage; PTT: photothermal therapy; ROS: reactive oxygen species; DCs: dendritic cells; GSH: glutathione; DAMPs: damage-associated molecular patterns; GPX4: glutathione peroxidase 4; PEG: polyethylene glycol; CTL: cytotoxic T lymphocyte; AMPK: AMP-activated protein kinase; PD-L1: programmed death-ligand 1; IFN: interferon; MDSCs: myeloid-derived suppressor cells; IDO: indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase; DOX: doxorubicin; BSA: bovine serum albumin; PDA: polydopamine; cGAS-STING: cyclic GMP-AMP synthase-stimulator of interferon genes; Tregs: regulatory T cells; CPT: camptothecin; ↑: increased; ↓: decreased.

CDDP, a widely used clinical chemotherapeutic agent, faces significant challenges due to acquired drug resistance. A primary mechanism involves elevated intracellular GSH level in tumor cells, which facilitates nucleophilic substitution reactions between CDDP and GSH to form GSH-Pt adducts. This process promotes drug inactivation and efflux, lowering intracellular active platinum concentration and DNA-binding capacity[145-147]. Recent studies reveal that CuET maintains chemical stability in TMEs with high GSH due to its low reduction potential, thereby evading GSH-mediated reductive inactivation. Moreover, CuET oxidizes zinc(II)-thiolate sites in critical proteins to induce cell death, positioning it as a promising alternative for treating CDDP-resistant cancers[148]. Lu et al. developed CuET nanoparticles (CuET NPs), which are internalized by cisplatin-resistant non-small cell lung cancer A549/DDP cells via endocytosis. CuET NPs accumulate in the cytoplasm and cytoskeleton, inducing NPL4 protein aggregation and triggering cuproptosis. Additionally, nuclear entry of CuET NPs causes DNA double-strand breaks, further enhancing anti-tumor efficacy. In A549/DDP tumor-bearing nude mice, CuET NPs demonstrated superior tumor inhibition compared to CDDP treatment, with normal liver/kidney function markers (AST, ALT, creatinine, urea) and no significant organ pathology, confirming reduced toxicity[149]. Intracellular symbiotic bacteria within tumor cells have been implicated in chemotherapy resistance through drug metabolism[150]. Tian et al. engineered a copper-based nanoadjuvant (CS/MTO-Cu@AMI), where released Cu2+ generates ROS via Fenton-like reactions to inactivate intracellular symbiotic bacteria and reverse chemoresistance. Combined MTO chemotherapy and cuproptosis induce double-strand DNA damage, activating the cGAS-STING pathway to drive proinflammatory cytokine secretion and evoke innate anti-tumor immunity. In MCF-7/ADR drug-resistant breast cancer models, CS/MTO-Cu@AMI achieved targeted tumor accumulation, significantly prolonged mouse survival, inhibited metastasis and post-surgical recurrence, and established long-term immune memory without normal tissue toxicity[151].

3.6 Other combination approaches

Radiotherapy induces tumor cell apoptosis by damaging DNA through high-energy ionizing radiation[158]. Despite its clinical utility, radiotherapy often causes collateral damage to adjacent normal tissues, resulting in severe toxic side effects[159]. Copper-based nanomaterials enhance tumor radiosensitivity via targeted delivery of high-atomic-number metals (e.g., copper), reducing the required radiation dose and minimizing off-target toxicity. Notably, radiotherapy upregulates cuproptosis-related proteins (FDX1, LIAS) in residual tumor tissues, indicating increased sensitivity to copper-induced cell death[160]. Conversely, cuproptosis disrupts Fe-S cluster proteins, impairing DNA repair and further sensitizing tumor cells to radiation[161]. This reciprocal enhancement establishes a synergistic therapeutic strategy combining copper nanomaterials with radiotherapy. The innovative design and mechanisms of these advanced nanoplatforms are encapsulated in Table 6, which provides a framework for the diverse approaches discussed in this section.

| Nanomaterials | Component | Summary of effects | Refs |

| Cu/APH-M | HPB, Au-Pt Nanoenzymes, Cu2+, CT26 Cancer Cell Membrane | Cuproptosis enhancement, radiotherapy, mature DCs ↑, T cell ↑, PD-L1 ↓, synergy with αPD-L1, abscopal tumor inhibition, immune memory | [161] |

| RCL@Pd@CuZ | Cu-MOF, Pd Nanoenzymes, Liposomes (RGD-DSPE-PEG, cholesterol, capsaicin) | Oxidative stress, hypoxia amelioration, radiotherapy, cuproptosis, mature DCs ↑, CD8+ T cell ↑, synergy with αPD-1, T cell antitumor activity | [162] |

| SCION-[Cu (DDC)2] | Cu-Fe Oxide NPs, DDC-Na | ER stress, ROS ↑, ferroptosis/apoptosis, CAF activity inhibition, EMT marker ↓, metastasis blockade, TAAs ↑, mature DCs ↑, CD8+ T cell ↑, Tregs ↓ | [164] |

| EsCu@TUP | TUP (MPC-co-HOPO, NR)), Es-Cu | TAAs capture/delivery to DCs, ROS ↑, AMF/thermal effect, CD8+ T cell/memory T cell ↑ | [165] |

| CuO@GDY | GDY, CuO, PEG | O2 ↑, HIF-1α/VEGF ↓, radiotherapy resistance reversal, apoptosis, DAMPs ↑, mature DCs ↑, CD8+/CD4+ T cell ↑ | [166] |

| CHP Nano-stimulator | Cu2+, Hf4+, PVP, STPP | Cuproptosis, radiotherapy, DAMPs ↑, mature DCs ↑, tumor antigen presentation, O2 ↑, HIF-1α/VEGF ↓, immunosuppressive cell ↓ | [167] |

| Vk3@Si@CuZnIONPs | CuZnIONPs, Silicon Dioxide, Vitamin K3 | MHT/thermal effects, ROS ↑, DAMPs ↑, mature DCs ↑, tumor antigen presentation, tumor-promoting factor ↓, TME reversal | [168] |

Pt: platinum; DCs: dendritic cells; PD-L1: programmed death-ligand 1; MOF: metal-organic framework; PEG: polyethylene glycol; NP: nanoparticle; DDC: diethyldithiocarbamate; ROS: reactive oxygen species; CAF: cancer-associated fibroblast; TAA: tumor-associated antigen; HIF: hypoxia-inducible factor; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; PVP: polyvinylpyrrolidone; STPP: sodium tripolyphosphate; DAMPs: damage-associated molecular patterns; TME: tumor microenvironment; RGD: Arg-Gly-Asp; ER: endoplasmic reticulum; Tregs: regulatory T cells; TAM: tumor-associated macrophage; MHT: magnetothermal therapy; AMF: alternating magnetic fields; EMT: epithelial-mesenchymal transition; TUP: tumor-penetrating magnetic particles; NR: nano-raspberries; HOPO: hydroxypyridinone; ↑: increased; ↓: decreased.

Li et al. engineered porous cubic Pd@CuZ nanomaterials. Pd nanoenzymes exhibit CAT activity, decomposing H2O2 to generate O2 and alleviate tumor hypoxia. The high atomic number (Z) of Pd amplifies X-ray photoelectric and Compton effects, enhancing radiosensitivity. Pd@CuZ synergistically potentiates oxidative stress with Cu MOFs, damaging tumor DNA and inhibiting repair to augment radiotherapy efficacy. In MC38 colon carcinoma-bearing C57BL/6 mice, RCL@Pd@CuZ combined with radiotherapy achieved a remarkable tumor inhibition rate exceeding 90%, which was significantly higher than radiotherapy alone. This regimen significantly increased DC maturation and CD8+ T-cell infiltration, and when further combined with anti-PD-1 antibody, the antitumor effect was enhanced without significant toxicity to body weight or major organs[162]. Pei et al. developed hollow mesoporous Prussian blue nanoparticles (HPB-Cu). Au-Pt bimetallic nanoenzymes decompose H2O2 to produce O2, boosting radiotherapy-induced cytotoxicity. Released Cu2+ suppresses Fe-S cluster protein synthesis in respiratory chain complexes, impeding DNA repair and heightening radiosensitivity. This cuproptosis-radiotherapy synergy triggers ICD, upregulating CRT, HSP70/90, and releasing ATP, TNF-α, and Caspase-1. HPB-Cu combined with radiotherapy and αPD-L1 reverses radiotherapy-induced PD-L1 upregulation, reducing immune evasion. In CT26 colorectal cancer models, this combination achieved complete primary tumor eradication, suppressed abscopal tumor growth, and established long-term immunological memory without significant toxicity to body weight or major organs[161].

Magnetothermal therapy (MHT) employs magnetic nanomaterials to generate localized heat under alternating magnetic fields (AMF), inducing tumor cell death[163]. Recent advances highlight MHT’s advantages including deep tissue penetration, precise controllability, excellent biosafety, and minimal off-target damage. Integrating copper-based nanomaterials with MHT enables AMF-triggered heat generation to stimulate drug release, achieving synergistic tumor therapy. Cai et al. engineered a multifunctional nanotherapeutic system (SCION-[Cu(DDC)2]). This complex exhibits superparamagnetism, generating thermal effects via Néel and Brownian relaxation under AMF, directly inducing ER stress and ROS production in tumor cells. Concurrently, it releases [Cu(DDC)2] complexes and Fe2+/Fe3+ to amplify oxidative stress, exacerbating tumor cell damage. SCION-[Cu(DDC)2] additionally suppresses cancer-associated fibroblast activity, downregulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition markers, and inhibits tumor migration/invasion to block metastasis. In 4T1 breast cancer models, the SCION-[Cu(DDC)2]-mediated combined magnetothermal therapy demonstrated precise tumor targeting and effective thermal effects, which not only potently suppressed primary tumor growth but also remodeled the tumor immune microenvironment to activate systemic antitumor immunity, significantly inhibiting tumor metastasis[164].

Chiang et al. developed tumor-penetrating magnetic particles (TUP). The charge-conversion property of PH copolymer combined with TUP’s MHT effect facilitates targeted accumulation and deep penetration into lung metastases. AMF-induced thermal effects from TUP’s magnetic nano-raspberries not only enhance TUP’s tumor penetration but also synergize with EsCu to intensify cytotoxicity and promote efficient TAA release. Captured TAAs by hydroxypyridinone groups trigger DC maturation, activating CD4+/CD8+ T cells and promoting immune cell infiltration into metastatic sites while disrupting immune evasion. In B16F10 lung metastasis models, TUP + AMF achieved targeted accumulation in lung metastases, significantly increased CD8+ T-cell infiltration, elevated IFN-γ/IL-10 levels, suppressed metastatic progression, and prolonged mouse survival[165]. This approach highlights the potential of combining cuproptosis with physical energy modalities like magnetic fields, a strategy further illustrated by the platforms in Table 6.

4. Challenges and Future Perspectives

4.1 Current challenges in the development of copper-based nanomaterial antitumor immunotherapy

Copper-based nanomedicines represent an emerging drug delivery platform with extensive exploration in anti-tumor immunotherapy. However, their clinical advancement faces critical challenges centered on mechanistic specificity, targeting precision, biosafety profiles, and clinical translatability. Overcoming these limitations holds significant potential to accelerate therapeutic innovation in this field. Below we outline key constraints currently impeding the development of copper-based nanomedicines.

4.1.1 Bottlenecks in material design and biosafety

Despite significant advances in copper-based nanomaterials for immunotherapy, their immunomodulatory mechanisms remain incompletely characterized. The influence of nanodrug physicochemical properties such as size, oxidation state, and surface charge on tumor immune responses also remains incompletely characterized, hindering the rational design of targeted immunomodulatory platforms. Concurrently, the in vivo pharmacokinetics of copper-based nanomedicines require deeper investigation, particularly regarding how nanoparticle surface modifications and intrinsic properties govern biodistribution and immune activation. Tumor heterogeneity and non-specific receptor expression further complicate targeted delivery, elevating off-target risks in vivo. Developing strategies to minimize unintended biodistribution represents a critical challenge. Regarding biosafety, hepatic and renal accumulation of nanomedicines poses risks of organ toxicity and functional impairment, necessitating innovative approaches to reduce non-tumor site retention. Additionally, monotherapy with copper-based nanomedicines often requires high doses to achieve efficacy, as systemic clearance diminishes effective intratumoral concentrations. Elevated dosing exacerbates risks associated with prolonged in vivo persistence. Consequently, optimizing therapeutic dosage through material engineering and surface functionalization to enable selective tumor targeting while maintaining efficacy remains a pivotal design consideration.

4.1.2 Barriers to clinical translation

The clinical translation of copper-based nanomedicine immunotherapy encounters multifaceted challenges. The central mechanism, cuproptosis, lacks specific biomarkers, impeding patient stratification and efficacy assessment and complicating the identification of suitable candidates for copper-based nanodrug therapy. Incomplete mechanistic understanding further constrains clinical trial advancement. Additionally, conventional nanodrug synthesis methods are labor-intensive and time-consuming, hindering uniformity control and efficacy standardization during large-scale manufacturing. Consequently, scalable production of copper-based nanodrugs represents a critical hurdle. Moreover, the underdeveloped regulatory framework for these nanomedicines significantly impedes their clinical adoption.

4.2 Future perspectives for copper-based nanomaterial antitumor immunotherapy

Copper-based nanodrugs demonstrate substantial therapeutic potential in antitumor immunotherapy, yet remain constrained by key challenges in mechanistic understanding and clinical translation. Overcoming these barriers necessitates rigorous research and innovative strategies. As advancements in copper nanomedicine continue, this field is poised to significantly advance tumor treatment paradigms. The following section outlines promising avenues for future development and emerging application scenarios.

4.2.1 Precision and multifunctionalization of material design