Kaili Lin, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Shanghai Ninth People's Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, College of Stomatology, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai 200011, China. E-mail: lklecnu@aliyun.com; linkaili@sjtu.edu.cn

Abstract

Peripheral nerve injury remains a significant clinical challenge, particularly in cases of long-gap defects. While autologous nerve grafting serves as the current gold standard treatment, its limitations include donor site morbidity and limited donor nerve availability. As a promising alternative, nerve guidance conduits (NGCs) have emerged within the field of tissue engineering. Incorporating electrical stimulation into NGCs has been shown to facilitate peripheral nerve repair by promoting Schwann cell migration and neurite extension. A significant advancement in this area is the application of piezoelectric biomaterials, which generate endogenous electrical signals from physiological mechanical stimuli. This self-powered mechanism eliminates the need for external power sources or additional surgical interventions. This review systematically examines the material design, fabrication strategies, and electromechanical properties of piezoelectric NGCs, along with their recent applications for enhancing Schwann cell function, guiding axonal growth, and promoting functional nerve recovery. Furthermore, it discusses current challenges and future directions, aiming to provide novel insights for the development of next-generation intelligent neural repair materials.

Keywords

1. Introduction

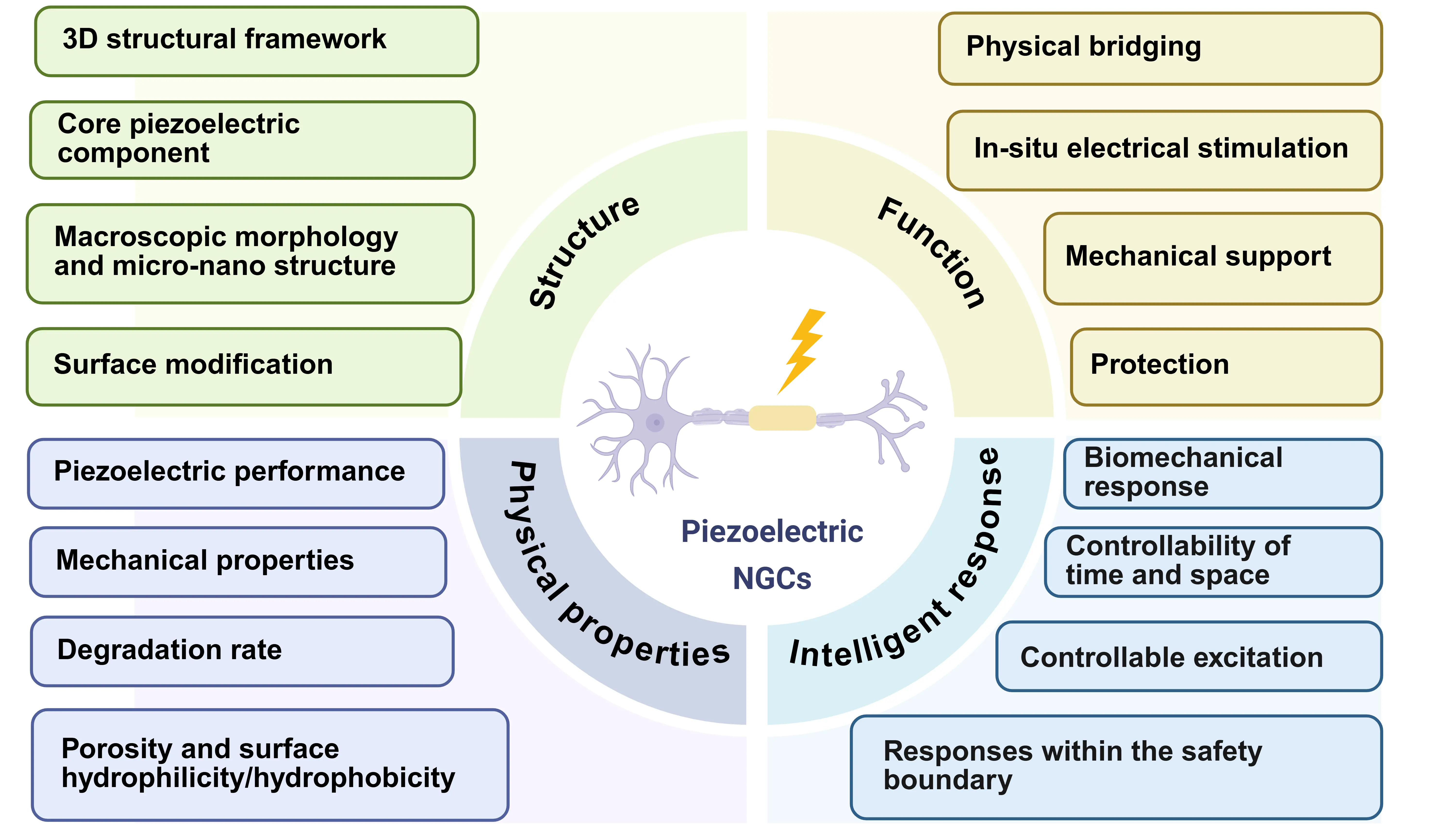

Peripheral nerve injury (PNI), which results from trauma or chronic diseases such as diabetes, poses a significant global clinical challenge and frequently leads to impairments in sensory, motor, and autonomic functions[1]. Despite being the clinical gold standard for addressing nerve defects, direct anastomosis and autologous nerve grafts have several limitations, like mismatched sizes and insufficient donor availability[2]. Advancements in tissue engineering have established artificial nerve guidance conduits (NGCs) as a promising alternative. Electrical stimulation has proven effective in enhancing nerve regeneration; however, traditional devices often suffer from limited penetration depth and cumbersome designs, which impede clinical translation[3]. Piezoelectric materials offer a promising solution by converting endogenous mechanical energy into localized electrical signals, thereby eliminating the need for external power sources such as batteries or wired connections. Their implantable and self-regulated nature enables on-site electrical stimulation, which minimizes signal attenuation through tissues and effectively overcomes depth-related limitations. By converting mechanical energy into electrical signals, piezoelectric materials can simulate the physiological activity of the nervous system, thereby offering dynamic, continuous bioelectrical stimulation and topographical structures to promote peripheral nerve regeneration (Figure 1)[4].

Figure 1. Schematic diagram depicting the key design principles of the piezoelectric NGCs for peripheral nerve regeneration. Created in Biorender.com. NGCs: nerve guidance conduits.

A key advantage of piezoelectric materials is their ability to recapitulate the native physiological microenvironment conducive to the repair of PNI[5]. First of all, the microenvironment of the peripheral nerve system resembles a meticulously organized pathway. Schwann cells (SCs) are pivotal in maintaining this order, secreting neurotrophic factors and aligning into structures to create a supportive scaffold for developing axons. Upon injury, the functional atrophy of SCs, coupled with excessive proliferation of fibroblasts, creates a fibrotic scar that blocks axon regrowth[6]. Without timely repair, chronically denervated target organs (e.g., muscle) deteriorate through atrophy and fibrosis[7]. To better simulate the microenvironment of peripheral nerves, researchers are developing piezoelectric NGCs with biomimetic microporous structures. Furthermore, electric stimulation (ES) generated by piezoelectric scaffolds is known to enhance SC migration, axon elongation, and myelination[8].

While significant progress has been made in research on piezoelectric NGCs for the repair of PNI, two critical scientific and technological challenges remain that constrain their clinical translation and practical efficacy: 1. Inadequate precise modulation of the mechano-electrical coupling mechanism and insufficient long-term in vivo stability[6], and 2. Most existing piezoelectric NGCs are functionally limited and have yet to achieve the integration of electrical signaling, micro-topographical structuring, and responsiveness to the physiological microenvironment. This review presents a systematic analysis of the material design, fabrication strategies, and electromechanical properties of piezoelectric NGCs, highlighting their recent applications in regulating Schwann cell function, guiding directional axonal growth, and facilitating functional neural recovery. It further addresses persisting challenges and outlines future research directions, offering innovative perspectives for advancing the design of next-generation intelligent neural regeneration materials.

2. Piezoelectric Biomaterials for the Repair of PNI

Piezoelectric NGCs are advanced biomaterial scaffolds that convert mechanical energy into electrical energy, providing in situ,

| Piezoelectric biomaterials | Stimuli | Preparation method | Piezoelectric performance | Outcomes | Limitations | Refs. |

| PCL/ZnO nanofiber | Mechanical stimulus | Electrospinning | Output voltage = 40-120 mV | Sciatic nerve repair time reduced to within 4 weeks. | In vivo degradation is unconfirmed. | [9] |

| PHBV/PLLA/KNN | Ultrasound | Spin coating | d33 = 1.59 pC N-1 | Engineered biodegradability | Material degradation and nerve repair rates are mismatched. | [10] |

| PPy/PDA/PLLA | N/C | Electrospinning | N/C | Dense regenerated neural tissues. | Lack of piezoelectric characterization. | [11] |

| Patterned PVDF/BaTiO3 | N/C | Electrospinning | Output voltage = 21.6 V | Tunable topography modulated scaffolds. | The therapeutic effect has not been verified in vivo. | [12] |

| PEDOT/BTO/Cellulose | Mechanical stimulus | Crosslinking | Output voltage = 8.22 mV | Excellent charge transfer ability. | Lack of in vivo biodegradability. | [13] |

| PLLA/PEG | Ultrasound | Electrospinning | Output voltage = 160 mV | Achieved autograft-comparable re-innervation. | Lacks large-animal validation. | [2] |

| PCL-β-Gly | Ultrasound | Electrospinning | Output voltage = 1.5 V | Achieve effective repair of long-gap nerve defects. | Lack of in vivo biodegradability. | [14] |

| TA-BaTiO3@PVA/glycerol-PCL/CNTs (TPPC) | Mechanical stimulus | Pre-gel- electrospinning synchronous winding method | Output voltage = 0.95 ± 0.02 V | Achieved autograft-comparable re-innervation. | Lack of in vivo biodegradability. | [15] |

| PCL/ZnO/rGO | Ultrasound | Microneedle and microchannel technology | Output voltage = 4.6 V | Accelerate the formation of microvessels. | Lack of in vivo biodegradability. | [5] |

| BaTiO3/collagen I hydrogel | Ultrasound | Solvothermal method and mixed with hydrogels | N/C | Verification by multiple animal models. | The piezoelectric coefficient is poorly characterized. | [16] |

NGCs: nerve guidance conduits; PCL: polycaprolactone; PHBV: poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate); PLLA: poly-L-lactic acid; PVDF: polyvinylidene fluoride;

2.1 Characterization, design and fabrication of piezoelectric NGCs

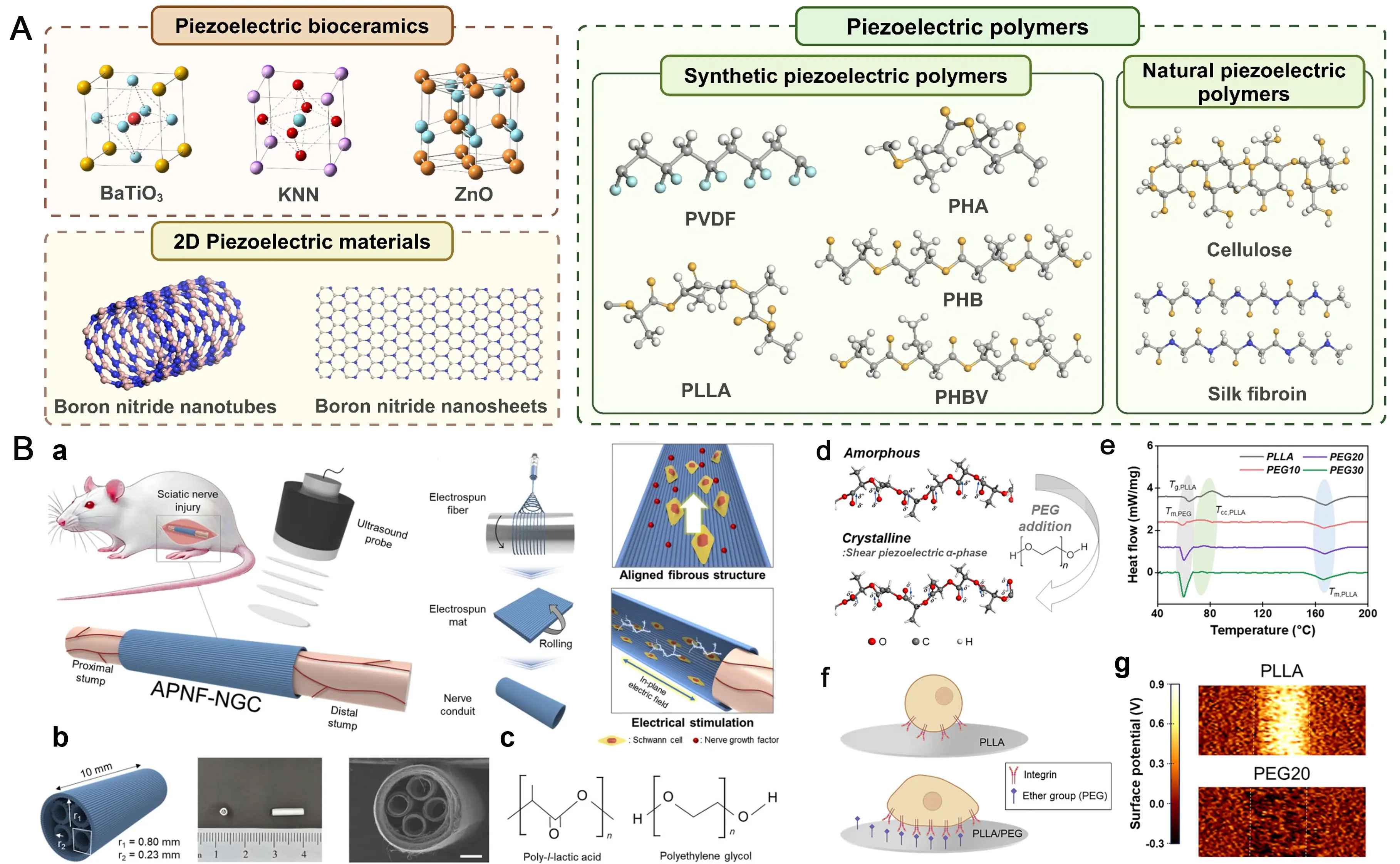

Piezoelectric materials for biomedical applications broadly fall into three primary categories: piezoelectric nanoparticles (e.g., barium titanate (BTO) and zinc oxide (ZnO)); piezoelectric polymers, such as poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA) and polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF); and composites, which integrate both components[17] (Figure 2). For example, BTO, a prominent ferroelectric material, converts mechanical energy via crystal lattice distortion under applied mechanical stress[18]. The piezoelectric coefficient (d33) of BaTiO3 ceramics synthesized via conventional solid-state sintering typically remains below 190 pC N-1[19]. This distortion induces a realignment of its ferroelectric polarization, generating an electrical potential. For PNI repair, BTO nanoparticles are often incorporated into biocompatible hydrogels alongside conductive materials to fabricate piezoelectric NGCs[13]. These composite NGCs exhibit enhanced electromechanical conversion efficiency and superior charge transfer capabilities.

Figure 2. Morphological characteristics of piezoelectric biomaterials in piezoelectric NGCs fabrication and their application examples. (A) The morphology of piezoelectric bioceramics and polymers. Republished with permission from[9]; (B) Wireless ultrasound-driven piezoelectric catheters based on highly oriented nanofibers for peripheral nerve regeneration. Republished with permission from[2]. NGCs: nerve guidance conduits; ZnO: zinc oxide; PLLA: poly-L-lactic acid; PVDF: polyvinylidene fluoride;

As for ZnO, with its typical hexagonal wurtzite structure, researchers have incorporated it into polymeric matrices by electrospinning technology to create piezoelectric scaffolds that generate ES upon physical deformation, effectively upregulating the expression of nerve growth factor (NGF) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in rats with PNI[9]. The piezoelectric coefficient of ZnO is highly dependent on multiple factors, including material morphology, fabrication process, and doping modifications[20]. The piezoelectric strain constant d33 of ZnO nanorods ranges from 0.9 to 9.5 pm/V, whereas that of bulk ZnO varies between 5.3 and

Piezoelectric polymers, such as PVDF and PLLA, have emerged as predominant materials in the field of peripheral nerve regeneration, owing to their superior flexibility, excellent biocompatibility, and tailorable degradability. Their piezoelectricity originates from the oriented arrangement of molecular chains and the ordered distribution of dipole moments. For example, Pi and colleagues employed electrospinning technology to fabricate piezoelectric polycaprolactone (PCL)/PVDF nanowires for PNI repair, with the resulting nanowires exhibiting a d33 of 14.07 pm V-1[21]. These aligned piezoelectric nanofiber bundles serve as a bifunctional scaffold, delivering both nanotopographical contact guidance to orient axonal growth and piezoelectric stimulation to supply endogenous bioelectrical signals, thereby synergistically enhancing nerve regeneration.

Regarding PLLA, it exhibits both biocompatibility and piezoelectric properties, yet it is hydrophobic and relatively rigid. To address these limitations, researchers have blended PLLA with PEG to fabricate anisotropic nanofibers, which effectively modulate mechanical properties, enhance α-phase crystallinity, and improve hydrophilicity. In a rat model with an 8 mm sciatic nerve defect, the nerve regeneration efficacy achieved with this material was comparable to that of autograft transplantation. Behavioral, motor function, and histological assessments collectively demonstrated its ability to accelerate functional recovery and promote axonal growth.

2.2 How piezoelectric stimulation promotes nerve regeneration

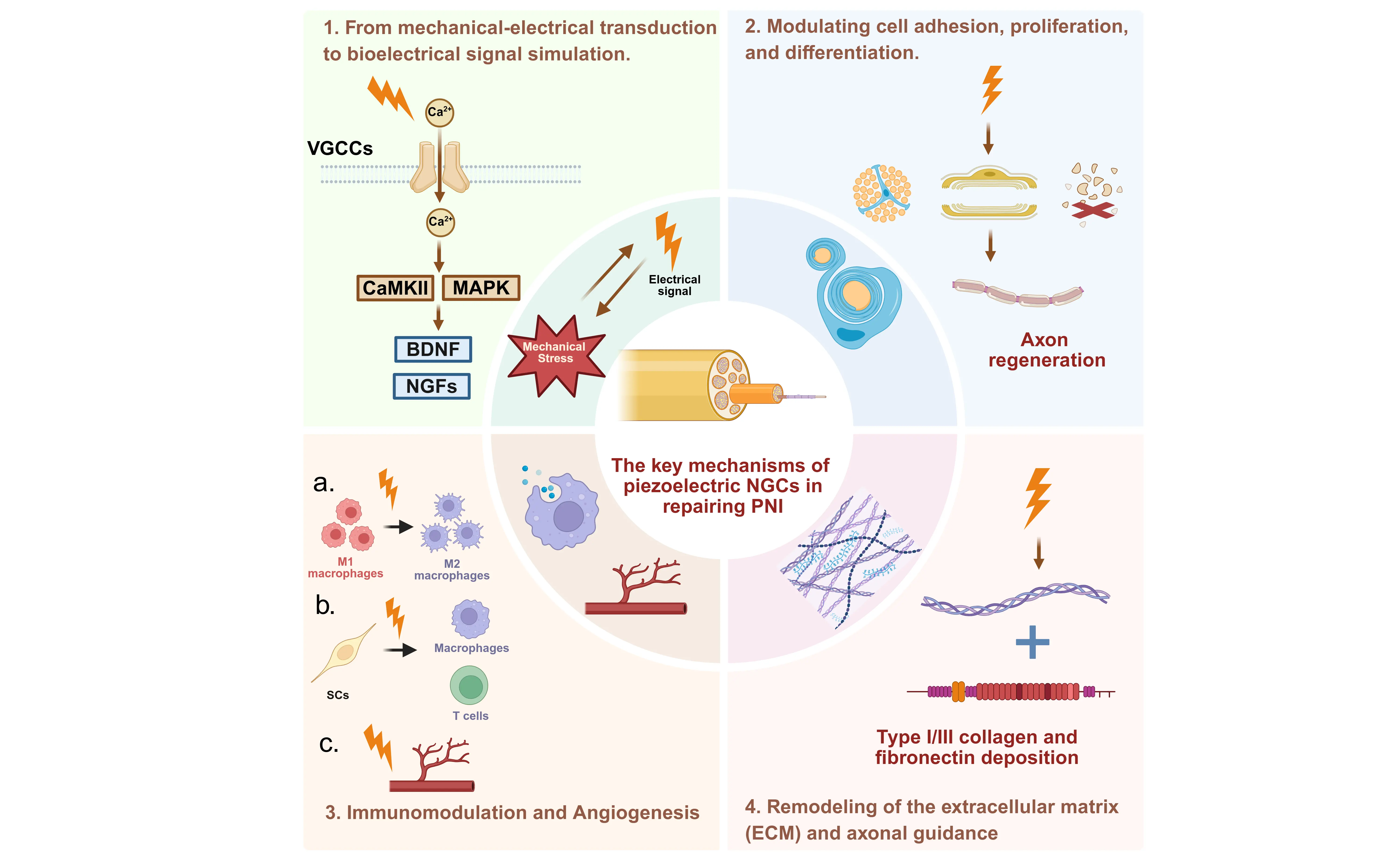

The piezoelectric effect in piezoelectric NGCs promotes nerve regeneration by converting mechanical forces into bioelectrical and biochemical signals that guide repair. Instead of relying on a single pathway, it functions through coordinated interactions across molecular, cellular, and tissue levels, forming an integrated signaling network[22]. This process transforms physical energy into instructive biological cues, providing a biomimetic and actively regulatable strategy for peripheral nerve regeneration (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Schematic diagram depicting the molecular mechanisms of the piezoelectric NGCs for peripheral nerve regeneration. Created in Biorender.com. NGCs: nerve guidance conduits; VGCCs: voltage-gated calcium channels; CaMKII: calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II; MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase;

2.2.1 From mechanical-electrical transduction to bioelectrical signal simulation

Under mechanical stimuli, including tissue motion and fluid flow, as well as external stimulation such as ultrasound, piezoelectric NGCs generate electrical signals within the physiological range (10-100 mV/mm). These electrical stimuli induce calcium influx through voltage-gated calcium channels, thereby activating downstream signaling pathways such as CaMKII and MAPK[23]. This molecular cascade upregulates the expression of neurotrophic factors (e.g., NGF, BDNF) and their corresponding receptors, which in turn promotes SC proliferation and phenotypic switching, enhances directional axon extension, and mitigates axonal

2.2.2 Modulating cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation

The mechano-electrical signals generated by the piezoelectric effect act directly on SCs as the “engine” of neural regeneration, driving their transition from quiescence to a repair phenotype. Mechanistically, piezoelectric stimulation promotes SC migration, myelin debris clearance, and remyelination via the integrin β1/FAK pathway, while regulating the Notch signaling pathway to prevent excessive proliferation and maintain a stable repair phenotype[4]. This dual action supports axonal regeneration through structural and trophic support, while also contributing to perineurial reconstruction.

2.2.3 Immunomodulation and angiogenesis

During peripheral nerve regeneration, the immunomodulatory activity of the piezoelectric effect is predominantly characterized by directing macrophage polarization toward the reparative M2 phenotype[25]. This phenotypic shift facilitates the phagocytic clearance of apoptotic cells and myelin debris, concomitantly attenuating the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines while augmenting the expression of reparative mediators. Notably, SCs also exert intrinsic immunoregulatory properties. Piezoelectric stimulation modulates the expression of immune-relevant molecules in SCs. This regulatory cascade subsequently influences T-cell activation and recruitment within the injured nerve microenvironment. Furthermore, activated SCs secrete pleiotropic factors such as glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor, which orchestrates the functional modulation of macrophages and T-cells, thereby establishing a coordinated “neuro-immune crosstalk” that favors regenerative processes[16].

Concurrently, the electrical stimulation generated by the piezoelectric effect activates the VEGF signaling pathway in vascular endothelial cells (VECs), promoting VEC proliferation and migration. This angiogenic response enhances local blood perfusion at the PNI injury site, ameliorates oxygenation and nutrient transport, and provides critical metabolic support for peripheral nerve regeneration[26].

2.2.4 Remodeling of the extracellular matrix (ECM) and axonal guidance

On the other hand, piezoelectric NGCs can orchestrate the synthesis and remodeling of the ECM, thereby promoting the ordered deposition of type I/III collagen and fibronectin. This process culminates in the formation of a biofunctional 3D scaffold that provides structural support for directed axonal outgrowth[13]. Concomitantly, localized mechanical cues generated by the piezoelectric effect modulate cellular mechanosensing via mechanosensitive ion channels, including Piezo1 and transient receptor potential vanilloid 4. Such regulation reinforces the adhesive interactions between neural cells and the ECM, while synergistically optimizing the biomechanical microenvironment to favor axonal regeneration.

2.3 The cutting-edge applications

Anatomically, a peripheral nerve resembles a highly organized cable comprising multiple fascicles enveloped by connective tissue[27]. This highly ordered, directional architecture must therefore be considered in the design of biomimetic piezoelectric nerve conduits. Although both PLLA and PVDF are piezoelectric biopolymers commonly processed into oriented structures via electrospinning for PNI repair, the slow degradation kinetics and associated toxicity risks have led to their diminished use in recent studies[28]. The optimal recovery period for nerve repair typically spans 3 to 4 months. However, natural piezoelectric materials, such as collagen and chitosan, are often inadequate for the repair of PNI due to their rapid degradation rates and insufficient mechanical properties[29]. Interestingly, a recent study demonstrated that β-glycine, a natural amino acid, has been successfully incorporated via electrospinning into the biodegradable polymer PCL to fabricate aligned piezoelectric NGCs for sciatic nerve regeneration[14]. Meanwhile, replacing traditional ultrasound with a massage gun as the vibration source presents no risk of thermal effects. This approach is also portable and user-friendly, requiring no professional operation, which supports its suitability for home or routine clinical use.

Beyond the incorporation of ordered structures, it is imperative to design and fabricate piezoelectric neural conduits with

2.4 Materials limitations

The failure of artificial NGCs often stems from two critical issues. Firstly, a mechanical mismatch arises when the conduit’s elastic modulus differs substantially from that of nerve tissue, potentially causing compression or structural failure[31]. Secondly, a detrimental inflammatory microenvironment develops inside the conduit, which involves SC pyroptosis and the production of inflammatory factors by pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages, creating a barrier to regeneration[32]. In response to these challenges, Wang and coworkers engineered an intelligent piezoelectric NGC based on a silk fibroin network via a dual cross-linking strategy. The resulting conduit is characterized by its nerve-matched mechanical properties, including an elastic modulus of 25.1±3.5 MPa and 80% elongation at break, effectively solving the problems of nerve entrapment and catheter collapse caused by mechanical

3. Conclusion and Perspectives

In conclusion, bionic piezoelectric NGCs have been fabricated using 3D printing and electrospinning to replicate the morphology and architecture of natural nerves. These devices incorporate piezoelectric nanoparticles (e.g., BTO, ZnO) within polymer matrices to generate endogenous electrical stimulation under mechanical stress, while piezoelectric polymers such as PVDF and PLLA are processed into highly aligned films that structurally mimic native nerve tissues. Nevertheless, the clinical application of synthetic piezoelectric polymers like PVDF is constrained by their slow degradation kinetics and potential cytotoxicity.

Naturally derived piezoelectric materials, including collagen, silk fibroin, and certain amino acids, offer improved biocompatibility but face challenges such as rapid degradation and mechanical mismatch with neural tissues. To overcome these drawbacks, recent strategies have focused on integrating natural piezoelectric components into synthetic polymers or hydrogel systems, thereby achieving NGCs with tunable degradation rates and matched mechanical properties.

Looking forward, the design of piezoelectric NGCs should evolve in several key directions:

1. Functionalization through multi-component integration: Incorporating conductive nanoparticles and anti-inflammatory agents will be crucial to enhance the electrical microenvironment and modulate the local immune response, thereby supporting sustained neural regeneration.

2. Structural biomimicry and precision guidance: Given the complex and hierarchical anatomy of peripheral nerves, next-generation piezoelectric NGCs should more accurately replicate the native neural microstructure, especially in topological alignment and compartmentalization. This biomimetic structural design can provide precise directional cues and effectively minimize axon misguidance in long-gap or multi-branch nerve injuries.

3. Smart and responsive system design: Future development should emphasize “smart” piezoelectric NGCs capable of dynamically responding to physiological mechanical stimuli (e.g., muscle movement, vascular pulsation) to deliver on-demand electrical cues, thereby creating a biomimetic and adaptive regenerative niche.

4. Translational considerations: Efforts must focus on scaling up fabrication techniques, ensuring reproducibility, and conducting systematic long-term in vivo studies to evaluate functional recovery, biodegradation, and biosafety. These are critical steps necessary for advancing toward clinical translation.

By integrating advanced materials engineering with nuanced biological design, piezoelectric NGCs hold significant promise to move beyond structural support toward actively orchestrating the complex process of peripheral nerve regeneration.

Authors contribution

Deng X: Investigation, writing–original draft, writing–review & editing.

Zhou Q: Data curation, writing-review & editing.

Shi R: Data curation, investigation, writing-review & editing.

Zhuang Y, Lin K: Supervision, project administration, methodology, funding acquisition, conceptualization, writing-review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

Kaili Lin is an Editorial Board Member of BME Horizon. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32271379), Shanghai’s Top Priority Research Center (2022ZZ01017), the CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS, 2019-I2M-5-037), Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (24YF2723100).

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

References

-

1. Nih LR, Gojgini S, Carmichael ST, Segura T. Dual-function injectable angiogenic biomaterial for the repair of brain tissue following stroke. Nat Mater. 2018;17(7):642-651.[DOI]

-

2. Jeon S, Kim D, Jo MY, Ryu CM, Cho DS, Choi BO, et al. Wireless acousto-piezoelectric conduit with aligned nanofibers for neural regeneration. Adv Mater. 2025;37(47):e03343.[DOI]

-

3. Meng X, Xiao X, Jeon S, Kim D, Park BJ, Kim YJ, et al. An ultrasound-driven bioadhesive triboelectric nanogenerator for instant wound sealing and electrically accelerated healing in emergencies. Adv Mater. 2023;35(12):2209054.[DOI]

-

4. Xu D, Fu S, Zhang H, Lu W, Xie J, Li J, et al. Ultrasound-responsive aligned piezoelectric nanofibers derived hydrogel conduits for peripheral nerve regeneration. Adv Mater. 2024;36(28):2307896.[DOI]

-

5. Hu C, Liu B, Huang X, Wang Z, Qin K, Sun L, et al. Sea cucumber-inspired microneedle nerve guidance conduit for synergistically inhibiting muscle atrophy and promoting nerve regeneration. ACS Nano. 2024;18(22):14427-14440.[DOI]

-

6. Wang Q, Wei Y, Yin X, Zhan G, Cao X, Gao H. Engineered PVDF/PLCL/PEDOT dual electroactive nerve conduit to mediate peripheral nerve regeneration by modulating the immune microenvironment. Adv Funct Mater. 2024;34(28):2400217.[DOI]

-

7. Schiaffino S, Dyar KA, Ciciliot S, Blaauw B, Sandri M. Mechanisms regulating skeletal muscle growth and atrophy. FEBS J. 2013;280(17):4294-4314.[DOI]

-

8. He L, Sun Z, Li J, Zhu R, Niu B, Tam KL, et al. Electrical stimulation at nanoscale topography boosts neural stem cell neurogenesis through the enhancement of autophagy signaling Biomaterials. 2021;268:120585.[DOI]

-

9. Mao R, Yu B, Cui J, Wang Z, Huang X, Yu H, et al. Piezoelectric stimulation from electrospun composite nanofibers for rapid peripheral nerve regeneration. Nano Energy. 2022;98:107322.[DOI]

-

10. Wu P, Chen P, Xu C, Wang Q, Zhang F, Yang K, et al. Ultrasound-driven in vivo electrical stimulation based on biodegradable piezoelectric nanogenerators for enhancing and monitoring the nerve tissue repair. Nano Energy. 2022;102:107707.[DOI]

-

11. Xiong F, Wei S, Wu S, Jiang W, Li B, Xuan H, et al. Aligned electroactive electrospun fibrous scaffolds for peripheral nerve regeneration. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2023;15(35):41385-41402.[DOI]

-

12. Kim JI, Hwang TI, Lee JC, Park CH, Kim CS. Regulating electrical cue and mechanotransduction in topological gradient structure modulated piezoelectric scaffolds to predict neural cell response. Adv Funct Mater. 2020;30(3):1907330.[DOI]

-

13. FZhao F, Liu G, Guan Y, Li J, Wang T, Zhao J, et al. An electromechanical converted bacterial cellulose based composite film for repairing peripheral nerve injury through mimicking physiological electrical signal. Adv Fiber Mater. 2025;7(6):1929-1948.[DOI]

-

14. Chen G, Hu Q, Tang C, Zhong S, Wang S, Jiang Z, et al. Biodegradable piezoelectric amino acid nerve guidance conduit repairs long-gap nerve defect under low frequency vibration from massage gun. Adv Funct Mater. 2025;18:e10947.[DOI]

-

15. Zhang J, Li F, Gao X, Qiu W, Xia B, He S, et al. Bamboo-inspired composite conduit accelerates peripheral nerve regeneration through synergistic oriented structure and piezoelectricity. Adv Mater. 2026;38(1):e09425.[DOI]

-

16. Shen J, Wu S, Wang Y, Yan Z, Liu T, Sun X, et al. Mechano-bioactive hydrogel bioelectronics for mechanical-electrical-bioenergetic conversion and glia-modulating neural regeneration. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):11582.[DOI]

-

17. Deng X, Zhuang Y, Cui J, Wang L, Zhan H, Wang X, et al. Open challenges and opportunities in piezoelectricity for tissue regeneration. Adv Sci. 2025;12(38):e10349.[DOI]

-

18. Wu L, Gao H, Han Q, Guan W, Sun S, Zheng T, et al. Piezoelectric materials for neuroregeneration: A review. Biomater Sci. 2023;11(22):7296-7310.[DOI]

-

19. Le J, Lv F, Lin J, Wu Y, Ren Z, Zhang Q, et al. Novel sandwich-structured flexible composite films with enhanced piezoelectric performance. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2024;16(1):1492-1501.[DOI]

-

20. Choudhury S, Wang ZL, Kim SW. Hydrogel-based piezoelectric materials and devices for implantable bioelectronics. Biomaterials. 2026;327:123768.[DOI]

-

21. Pi W, Rao F, Cao J, Zhang M, Chang T, Han Y, et al. Sono-electro-mechanical therapy for peripheral nerve regeneration through piezoelectric nanotracts. Nano Today. 2023;50:101860.[DOI]

-

22. Cai Y, Wang P, Li Y, Tang TW, Zhang L, Shu H, et al. Triple-cue-guided multichannel hydrogel conduit to synergistically enhance peripheral nerve repair. ACS Nano. 2025;19(24):22163-22178.[DOI]

-

23. Zhang J, Liu C, Li J, Yu T, Ruan J, Yang F. Advanced piezoelectric materials, devices, and systems for orthopedic medicine. Adv Sci. 2025;12(3):2410400.[DOI]

-

24. Wang F, Qiu J, Guan S, Chen S, Nie X, Fu Z, et al. An ultrasound-responsive hydrogel with piezoelectric-enhanced electrokinetic effect accelerates neurovascular regeneration for diabetic wound healing. Mater Today. 2025;84:48-64.[DOI]

-

25. Song J, Liao C, Yuan Z, Yu X, Cui J, Ding Y, et al. Electrically conductive and anti-inflammatory nerve conduits based on chitosan/hydroxyethyl cellulose hydrogel for enhanced peripheral nerve regeneration. Carbohydr Polym. 2025;368:124178.[DOI]

-

26. Ma Y, Wang H, Wang Q, Cao X, Gao H. Piezoelectric conduit combined with multi-channel conductive scaffold for peripheral nerve regeneration. Chem Eng J. 2023;452:139424.[DOI]

-

27. Ide C, Tohyama K, Tajima K, Endoh K, Sano K, Tamura M, et al. Long acellular nerve transplants for allogeneic grafting and the effects of basic fibroblast growth factor on the growth of regenerating axons in dogs: A preliminary report. Exp Neurol. 1998;154(1):99-112.[DOI]

-

28. Brennan NM, Evans AT, Fritz MK, Peak SA, von Holst HE. Trends in the regulation of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS): a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(20):10900.[DOI]

-

29. (a) Kang M, Lee DM, Hyun I, Rubab N, Kim SH, Kim SW. Advances in bioresorbable triboelectric nanogenerators. Chem Rev. 2023;123(19):11559-11618.[DOI](b) Zheng Q, Zou Y, Zhang Y, Liu Z, Shi B, Wang X, et al. Biodegradable triboelectric nanogenerator as a life-time designed implantable power source. Sci Adv. 2016;2(3):e1501478.[DOI]

-

30. Yang S, Chen L, Bai C, Zhao S, Wu H, Dong X, et al. Polymer scaffolds for peripheral nerve injury repair. Prog Mater Sci. 2025;153:101497.[DOI]

-

31. Wu S, Qi Y, Shi W, Kuss M, Chen S, Duan B. Electrospun conductive nanofiber yarns for accelerating mesenchymal stem cells differentiation and maturation into schwann cell-like cells under a combination of electrical stimulation and chemical induction. Acta Biomater. 2022;139:91-104.[DOI]

-

32. Li W, Liang J, Li S, Wang L, Xu S, Jiang S, et al. Research progress of targeting NLRP3 inflammasome in peripheral nerve injury and pain. Int Immunopharmacol. 2022;110:109026.[DOI]

-

33. Wang JY, Yuan Y, Zhang SY, Lu SY, Han GJ, Bian MX, et al. Remodeling of the intra-conduit inflammatory microenvironment to improve peripheral nerve regeneration with a neuromechanical matching protein-based conduit. Adv Sci. 2024;11(17):2302988.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite