Abstract

Bone tissue engineering (BTE) is pivotal for addressing bone defects. It integrates biomaterials, cells, and bioactive factors to mimic the natural bone microenvironment, thereby promoting bone regeneration and repair. In this system, scaffolds provide physical support and nutrient transport for cells. Three-dimensional (3D) printing revolutionizes BTE by fabricating customized scaffolds tailored to individual patients. As the cornerstone of 3D bioprinting, bioinks must meet strict biocompatibility and printability requirements to drive BTE advancement. In this review, we first explore the principles, advantages, and limitations of various bioprinting techniques. Furthermore, we also summarized recent breakthroughs and merits of three key photo-crosslinking reactions, including photoinitiated free radical crosslinking, photoclick crosslinking, and photo-conjugation crosslinking. Moreover, this review focused on the properties of natural polymers, synthetic polymers, and calcium phosphate-based inorganic materials in bioink formulation, as well as their BTE applications. Finally, a concise outlook on the future advancement of photocurable bioinks was provided.

Keywords

1. Introduction

With the acceleration of the aging process of the population and the increase in various trauma accidents, the incidence of bone defect-related diseases has become a significant clinical challenge. This not only seriously affects the quality of life of patients but also exerts huge pressure on medical resources. As a highly promising treatment method, bone tissue engineering aims to mimic the microenvironment of natural bone by combining biomaterials, cells, and bioactive factors, thereby facilitating the regeneration and repair of bone tissue. It has thus become a promising research focus in solving the problem of bone defects[1].

As a crucial component of bone tissue engineering, scaffolds are indispensable. They provide physical support for cells and simulate the structure of the extracellular matrix, enabling cells to adhere, spread, and migrate on their surface and inside. Furthermore, the porous structure of scaffolds is vital for the transport of nutrients, the excretion of metabolic products, and the ingrowth of blood vessels. Appropriate pore size and connectivity can ensure that cells receive sufficient nutrient supply and maintain normal physiological functions. In addition, scaffolds can serve as delivery vehicles for bioactive factors, enabling precise regulation of cellular behavior and promoting bone tissue regeneration. Through rational design and construction of engineered bone scaffolds, a suitable three-dimensional (3D) microenvironment is provided for the adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation of seed cells, while guiding the growth and remodeling of new bone tissue, ultimately achieving functional repair of bone tissue[2].

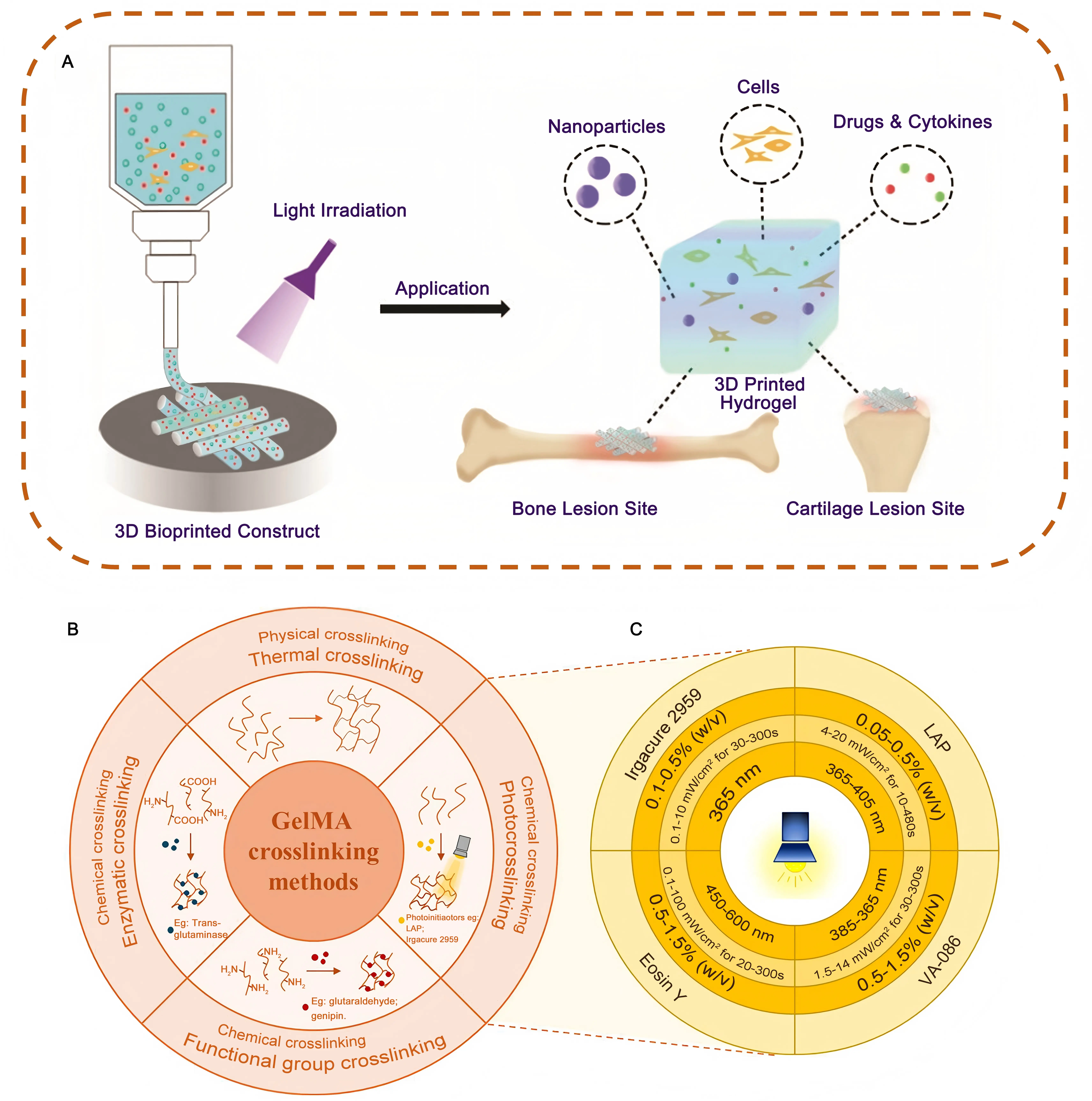

In recent years, 3D printing technology has gained significant prominence in the construction of engineered bone scaffolds due to its unique merits. Compared with traditional methods, 3D printing can accurately construct scaffolds with complex 3D structures based on computer-aided design (CAD) models, enabling precise regulation of the internal pore structure, external dimensions, and mechanical properties of the scaffolds[2]. The 3D hydrogel scaffold prepared by photocrosslinking technology can not only well match the bone defect morphology and mechanical needs of different patients, but also load nanoparticles, cells, drugs, etc., thereby enabling personalized treatment (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. (A) Schematic illustration of photo-crosslinkable hydrogels for bioprinting bone and cartilage tissues[3]; (B) GelMA primary crosslinking methods; (C) Main photoinitiators employed for GelMA photocrosslinking[4]. GelMA: gelatin methacrylate; LAP: lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate.

The core feature of 4D printing is the introduction of the time dimension, that is, intelligent material printing components can achieve programmable dynamic evolution of shape, performance, or function under preset external stimuli[5]. Bioprinting, as a specific application of 3D printing in regenerative medicine, refers to the fabrication of scaffolds from bioinks containing living cells. The core focus lies on cell activity, biocompatibility, and the ability to support tissue regeneration, such as cell proliferation, differentiation, and osteogenesis in vivo[6]. In the field of bone tissue engineering, although 4D printing can reduce soft tissue injury and bleeding during stent implantation with the virtue of the shape memory effect and programmable deformation ability[7], compared with 3D printing, the technology is still in the development stage, especially, the manufacturing process and parameter optimization need to be further studied. The long-term biosafety, degradation products, and potential impact on the cell microenvironment of intelligent materials need to be comprehensively evaluated[5], and the controllable realization of precise stimulation sources required for dynamic deformation in vivo is still a great challenge[7].

In the field of bone tissue engineering, 3D printing technology relies on bioink as a key element. Bioink is a biocompatible material, usually composed of biopolymers, cells, and bioactive factors. It can maintain a specific shape during printing and provide a suitable environment for cells. The three-dimensional structure formed by bioink after printing must not only have good mechanical properties to support cell growth and tissue construction, but also be able to replicate the biological activities of the extracellular matrix to enhance cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation, thereby accomplishing bone tissue regeneration[8,9].

In key areas such as cell loading, bionic microenvironment construction, printability, and functional integration, the performance of bioink is significantly better than that of traditional bone repair materials. The specific advantages are as follows: traditional ceramic/metal scaffolds need to introduce cells through subsequent inoculation, which easily leads to uneven cell distribution and low load density, while bioink can achieve direct encapsulation of living cells and maintain a high cell loading density

Bioinks can be classified into natural polymer, synthetic polymer, and composite bioinks. Natural polymer bioinks, such as collagen, chitosan, and sodium alginate, exhibit good biocompatibility and bioactivity and can interact with cell-surface receptors to facilitate cell adhesion and proliferation. However, natural polymers have relatively weak mechanical properties, and there are certain differences in their sources and quality, which limit their independent use in some bone tissue engineering applications with high requirements for mechanical properties[8,9]. Synthetic polymer bioinks, such as polylactic acid (PLA) and polycaprolactone (PCL), exhibit adjustable mechanical characteristics and degradation kinetics, which can meet the demands of various bone tissue engineering scenarios. However, the biocompatibility of synthetic polymers is often not as good as that of natural polymers, so surface modification or composite use with natural polymers is required to improve their cell affinity[1,9]. Composite bioinks are formed by the integration of synthetic polymers and natural polymers. For example, blending sodium alginate with polyethylene glycol (PEG) can improve the mechanical properties of the bioink while maintaining its good biocompatibility. In addition, composite bioinks can also be added with cells and bioactive factors to further enhance their biological functions[9].

In the presence of a photoinitiator, the unsaturated double bonds in the bioink polymerize upon irradiation with light of a specific wavelength, forming a three-dimensional network. By changing the concentration of the photocrosslinking agent, efficient crosslinking can be achieved without affecting the biological properties (Figure 1B,C). Photocrosslinking reactions have advantages such as fast reaction speed, precisely controllable crosslinking degrees, and little impact on biological activity, making it an ideal crosslinking method for preparing bioinks for bone scaffolds[16]. By adjusting the formulation of photo-crosslinkable bioinks (such as changing the type and concentration of polymers and the content of crosslinking agents), crosslinked scaffolds exhibit flexibly tunable mechanical properties that can meet the mechanical requirements of diverse bone tissue regions. For example, in the remediation of bone defects in load-bearing skeletal areas, scaffolds with higher mechanical strength are required; whereas in

2. Bioprinted Scaffolds in Bone Tissue Engineering

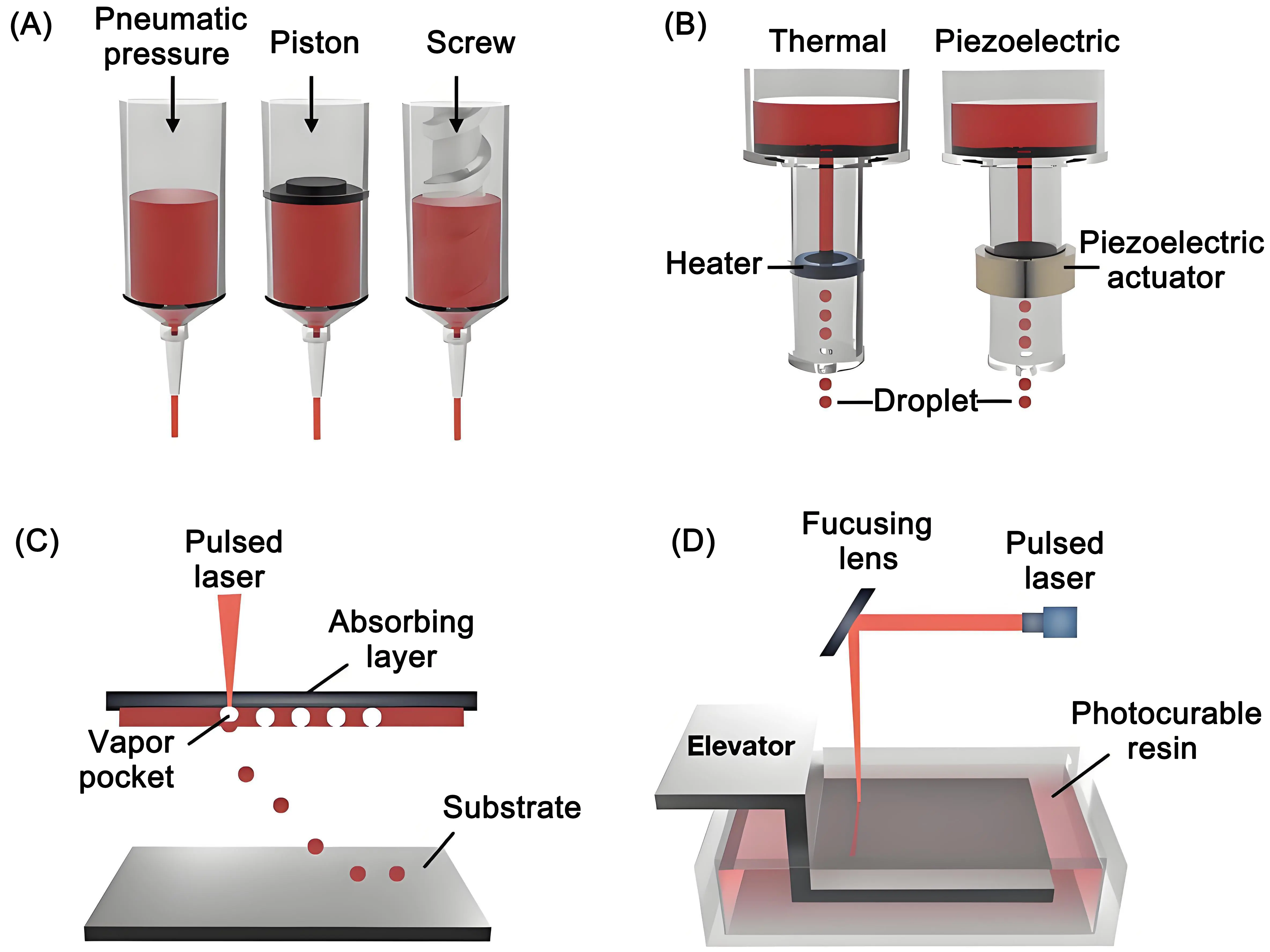

3D printing technologies (Table 1) can achieve precise control over the formation of hydrogels by controlling the irradiation time, area, and intensity, including extrusion-based bioprinting, inkjet-based bioprinting, laser-assisted bioprinting, and

Figure 2. Schematic illustration of bioprinting methods used in bone tissue engineering. (a) Bioprinting based on extrusion; (b) Bioprinting relying on inkjet, (c) Bioprinting assisted by laser; (d) Light-mediated (stereolithography) 3D bioprinting systems[21].

3. Types of Photo-Crosslinking

In tissue engineering, lithographic techniques can be used to irradiate specific areas through a photomask, thereby preparing hydrogel scaffolds with complex patterns to guide cell growth and tissue formation (Table 2). In contrast, non-photo-crosslinking methods, such as thermal crosslinking and chemical crosslinking, have difficulties in achieving such precise spatial control and often undergo crosslinking reactions uniformly throughout the system (Figure 1B)[36].

| Type | Mechanism | References |

| Photo-Initiated Free Radical Crosslinking Reaction | Light irradiation excites the photoinitiator to generate free radicals, triggering monomer polymerization and crosslinking into a 3D network hydrogel | [22-25] |

| Photo-Click Crosslinking Reaction | Photo-click cross-linking uses light to trigger specific chemical reactions that cross-link molecules into a hydrogel network | [26-29] |

| Photo-Coupling Crosslinking Reaction | Light-induced photo-coupling crosslinking forms covalent bonds between polymer chains, constructing a 3D hydrogel network | [30-35] |

Photo-crosslinking reactions usually occur at room temperature and normal pressure without the need for harsh conditions such as high temperature and high pressure[37]. This is particularly beneficial for some bioactive molecules or cells that are sensitive to temperature, pH, etc. When preparing hydrogels for sustained drug release, if chemical crosslinking is used, toxic crosslinking agents may be required, or the reaction may need to be carried out at a relatively high temperature, which may compromise the drug’s activity. However, photo-crosslinking can be carried out under mild conditions, better preserving the activity of the drug.

Combined with advanced lithography, 3D printing, and other techniques, photo-crosslinking technology can produce hydrogels with complex three-dimensional structures. In the fabrication of microfluidic chips, photo-crosslinking can be used to precisely prepare hydrogel components with complex structures such as microchannels and microcavities, achieving precise control of fluid[38].

3.1 Photo-induced polymerization crosslinking

Photo-Induced Polymerization Crosslinking, as an important method for preparing hydrogels, has attracted much attention. It refers to the process in which, under light irradiation, a photo-initiator absorbs photon energy, jumps to an excited state, decomposes to generate free radicals, initiates the polymerization of double bonds of monomer molecules, and cross-links between molecules to form a three-dimensional network-structured hydrogel. Compared with non-photo-type hydrogel preparation methods, it has advantages such as precise spatiotemporal control, non-physical contact, and fast reaction speed.

In the early stage, Roose et al.[24], introduced a semi-empirical scaling model to explain the kinetics of free-radical polymerization of acrylated urethane pre-polymers in the solid phase. They studied the relationship between the polymerization rate and the functional conversion rate and compared it with experimental kinetics. It provides a fundamental kinetic analysis framework for subsequent research, and for the first time quantifies the “reaction rate-conversion” relationship in photoinitiated free radical polymerization, promoting the field from qualitative description to quantitative analysis.

Subsequently, Gu et al. prepared a biodegradable elastomer device and studied the effects of various parameters on the stability of the therapeutic protein vascular endothelial growth factor during a photo-triggered free-radical cross-linking reaction. Based on previous research on reaction kinetics, their work was extended to the study of protein stability in the biomedical field[23].

Sun et al. used the camphorquinone/diphenyliodonium hexafluorophosphate as a blue-light-initiating system to study the blue-light polymerization performance and cross-linking characteristics of hydrogel polymerization precursor solutions under different conditions. They drew on prior analytical work on the correlation between “reaction parameters and product properties” and proposed an empirical model for mechanical properties. This model quantified the relationship between reaction parameters and the mechanical properties of hydrogels in blue-light initiated systems, providing an operable theoretical tool for the precise regulation of the properties of blue-light initiated hydrogels[25].

Bao et al. carried out a comprehensive assessment of the technological evolution path, current uses, and intrinsic drawbacks of photoinitiated free-radical crosslinking reactions. They pointed out that a central problem with this technology is its tendency to generate non-uniform network structures, leading to structural flaws and a decline in mechanical stability. To tackle this problem, based on the existing studies in polymerization kinetics and initiator systems, the team put forward an inventive “photo-coupled reaction crosslinking strategy”[22]. This new approach provides a significant improvement in material characteristics compared to traditional Photoinitiated Free-Radical Polymerization. It can boost tensile strength by up to 20 times and toughness by up to 70 times, while keeping the gelation time within seconds. More crucially, by reducing dependence on high-concentration cytotoxic free radicals during network formation and by facilitating a more uniform microstructure, this strategy effectively alleviates the major biocompatibility issues associated with conventional free-radical crosslinking. Moreover, the combination of excellent mechanical properties and the possibility of in situ gelation creates opportunities to develop hydrogels with improved tissue adhesion. This progress overcomes significant barriers to clinical implementation, especially in fields such as tissue repair and wound care. As a result, it greatly broadens the practical scope of application of photopolymerization technology in the biomedical domain.

3.2 Photo-click crosslinking reaction

Photo-click crosslinking is a process in which molecules are crosslinked via specific light-induced reactions to form a hydrogel network. It is characterized by high efficiency, high selectivity, and mild reaction conditions. Compared with non-photo-based hydrogel preparation methods, it offers significant advantages, such as precise spatiotemporal control and mild reaction conditions, which are conducive to maintaining the activity of bioactive molecules and cells.

In terms of the historical context of research, Stuckhardt et al. reported the photoinduced coupling reaction between acylsilanes and indoles early on[28]. This reaction can mostly occur with quantitative yield under mild conditions of 415 nm light irradiation. Through photoinduced formation of siloxycarbenes and subsequent insertion into the indole N-H bond, stable silylated N,O-acetals are provided, demonstrating that this remarkably efficient and entirely atom-economical coupling procedure is applicable to intricate conjugate systems and polymer chain conjugation.

Subsequently, Wang et al. synthesized injectable hydrogels based on hyaluronic acid with a progressive augmentation of mechanical characteristics through photo-cross-linking reactions and Diels-Alder (DA) reactions triggered by thermal means[29]. Catalyzed by lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate, hyaluronic acid-furan photo-cross-linking can rapidly gel within 30 s, and the characteristics related to mechanical behavior can be regulated by the exposure time. Thermally-induced DA click chemistry further enhances the cross-linking density and mechanical properties. It continues the idea of “light-mediated rapid crosslinking” and enables rapid hydrogel formation via photocrosslinking. It breaks through the limitations of single photocrosslinking in regulating performance, expands the adjustable range of hydrogel properties through a “light-thermal” two-step reaction, and achieves injectability, which better aligns with the needs of biomedical applications.

Sánchez-Sid et al. followed the method of constructing polymer networks via photo-initiated click reactions and proposed a strategy to improve the properties of chitosan-based hydrogels by forming semi-interpenetrating polymer networks (semi-IPNs)[27]. They first obtained a synthetic polymer through photo-initiated free radical click reactions, then added its components into the chitosan solution, and formed a semi-interpenetrating polymer network upon ultraviolet irradiation. The study evaluated the effects of different crosslinking degrees and chitosan/polymer ratios on the rheological properties of the hydrogels and found that the hydrogels exhibited optimal rheological properties at a moderate crosslinking degree (8%).

Pereira et al. synthesized and photo-cross-linked cell-guiding pectin hydrogels incorporating peptide cross-linkers that can be degraded by cells and adhesion ligands specific to integrins[26]. The resulting hydrogels, which are degradable by proteases, were formed rapidly via photo-initiated thiol-norbornene click chemistry in the presence of dermal fibroblasts. These hydrogels exhibited adjustable properties and could regulate the behaviors of embedded cells. When keratinocytes are placed atop hydrogels containing fibroblasts, this can replicate the natural structure of the skin. It upgrades photocrosslinking hydrogels from a “mere carrier” to a “functional platform capable of dynamically interacting with cells”, making them more aligned with the requirement of “constructing a bionic microenvironment” in tissue engineering.

Bao et al. emphasized in their review the technical development history, application status, advantages, and technical bottlenecks of photo-cross-linked hydrogels based on Photo-Induced Polymerization Crosslinking reactions, photography-induced cross-linking chemical reactions, or photo-coupling cross-linking reactions[22]. They noted that photo-click cross-linking reactions have broad potential for application in medical fields. They also proposed a non-radical photo-cross-linking strategy by their research group, which uses the photo-cleavage of photocaged molecules to release active groups and trigger cross-linking via photo-coupling reactions. This strategy realizes low toxicity and controllable construction of

3.3 Photo-coupling crosslinking reaction

Photo-coupling crosslinking involves the light-induced formation of covalent bonds between polymer chains, constructing a

The development of hydrogels via photo-coupling crosslinking has been advanced by the contributions of numerous scholars. Early studies laid the foundation, while subsequent studies have continuously deepened and expanded its application. Bao Bingkun and others used photo-cleavage of photocaged molecules to release active groups to trigger coupling crosslinking, i.e., the

Based on the strategy proposed by Bao Bingkun and others, Jeon constructed a negatively charged photo-crosslinkable alginate hydrogel and evaluated its biocompatibility systematically[32]. This provides specific material design schemes and experimental data support for the application of photocrosslinked hydrogels in fields such as bone tissue engineering, transforming Bao Bingkun’s “strategic framework” into “practical material examples”.

Majid et al. synthesized a series of biodegradable and biocompatible hydrogels from dextran methacrylate and poly

Based on previous research, Ma et al. reviewed the application of photo-crosslinkable hydrogels in improving wound healing

Inspired by photosynthesis, Huang et al. used riboflavin and H2O2 to achieve a sustainable cyclic photo-crosslinking reaction, resulting in silk fibroin hydrogels with excellent mechanical properties and efficient preparation[31]. The hydrogels have excellent elasticity and recoverability, and the encapsulated adipose stem cells can stimulate cell proliferation and maintain stemness. Moreover, they can be applied across various material-forming platforms, enabling breakthrough performance improvements and expanded applications.

Nelson et al. proposed 1,2-dithiolane as a dynamic covalent photo-crosslinking agent to prepare multiresponsive dynamic hydrogels, endowing the hydrogels with responsiveness to a variety of stimuli[35]. Lipoic acid serves as a paradigm; dithiolane cross-linking occurs under physiological conditions. Subsequently, cell encapsulation is accomplished via initiator-free light-triggered

4. Photocurable Bioinks Synthesis

The resulting hydrogels have various light-induced dynamic responses, can control network performance through reaction with alkenes, and achieve rapid sample degradation and post-gel hardening using complementary photochemical methods. Moreover, this approach innovated in the design and regulation of crosslinking agents and expanded the potential applications of

| Material | Bioink preparation | Characteristics | Applications | References |

| GelMA | Gelatin reacted with methacrylic anhydride (flexible degree of substitution), dissolved with photoinitiator (e.g., LAP or Irgacure 2959). | High biocompatibility, tunable stiffness (1-50 kPa), supports cell adhesion/proliferation. | Cartilage regeneration, skin tissue engineering, vascular networks. | [39] |

| PEGDA | PEG acrylated via reaction with acryloyl chloride, mixed with photoinitiator (MW: 700-10,000 Da). | Low immunogenicity, adjustable crosslinking, and lacks cell adhesion sites (requires RGD modification). | Drug delivery, microfluidics, soft tissue scaffolds. | [40] |

| HAMA | HA functionalized with methacrylic anhydride, purified, and combined with photoinitiator. | High hydrophilicity, promotes cell migration and tunable degradation. | Wound healing, corneal repair, nerve regeneration. | [41] |

| Alginate-GelMA Composite | Alginate blended with GelMA, partially crosslinked with Ca²⁺ before photocuring. | Dual crosslinking (ionic + photopolymerization), enhanced strength. | Osteochondral repair, cardiac patches. | [42] |

| SilMA | Silk degummed, methacrylated | High mechanical strength. | Bone regeneration, ligament repair. | [43] |

| Decellularized ECM (dECMA) | Tissue decellularized, ECM methacrylated, and photo-crosslinked. | Retains native ECM (collagen, growth factors), high bioactivity. | Organ-specific regeneration (e.g., liver, heart). | [44] |

| PLGA-PEG Photocurable Microspheres | PLGA-PEG acrylated, emulsified into microspheres, and UV-crosslinked. | Controlled drug release, porous microsphere structure. | Cancer drug carriers, tissue fillers. | [45] |

| CNC-Reinforced Bioink | CNC dispersed in GelMA/PEGDA, photocured. | Enhanced stiffness (2-5× modulus increase), anisotropic structures. | Bone repair, high-strength hydrogels. | [46] |

GelMA: gelatin methacrylate; LAP: lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate; PEGDA: poly (ethylene glycol) diacrylate; HAMA: hyaluronic acid methacryloyl;

4.1 Natural polymers

One of the primary benefits of natural polymers is their biocompatibility and biodegradability. These properties can significantly facilitate cell adhesion, movement, differentiation, and tissue regeneration[47-50]. Moreover, after undergoing photocrosslinking, the mechanical characteristics of natural polymers, which are otherwise lacking, can be marginally enhanced. This enhancement makes it feasible to fabricate bone scaffolds with specific geometries via photolithography-based 3D bioprinting[51]. As a result, natural polymers find wide-ranging applications. Some of these polymers include gelatin methacrylate (GelMA)[52-54], methacrylated hyaluronic acid (HAMA)[55-57], silk methacrylate (SilMA)[58-60], and methacrylated chitosan (CSMA)[50,61].

4.1.1 Gelatin methacryloyl

Gelatin is a partially hydrolyzed product of collagen and typically derived from the skin, bones, and tendons of cattle, pigs, or fish. Its molecular structure retains the triple-helical domains and cell-adhesive sequences (e.g., arginine-glycine-aspartic acid, RGD) of natural collagen, endowing it with excellent biocompatibility and cell affinity. Gelatin is water-soluble at room temperature and forms a thermo-reversible gel (gelation temperature ~25-30 °C). However, pure gelatin has low mechanical strength (elastic modulus < 10 kPa) and is susceptible to enzymatic degradation, necessitating chemical modification or composite strategies to enhance stability.

Gelatin, a biodegradable polypeptide, is obtained through the partial hydrolysis of collagen. Owing to its excellent biocompatibility, bioactivity, and cell-adhesion properties, it has found widespread application in bone tissue engineering (BTE). When gelatin reacts with methacrylic anhydride (MA), it can be modified into GelMA, which gains the capacity for photocrosslinking[62]. GelMA shares cytocompatibility characteristics similar to those of the extracellular matrix. As a result, it is well-suited for 3D cell culture. Studies have demonstrated that cells encapsulated in GelMA display high viability[63]. Nonetheless, varying polymer concentrations (commonly around 10%) and different substitution rates (such as 80%) might impede cell proliferation in the spatial environment. To address this, GelMA with a functionalization degree ranging from 20% to 80% is utilized to create stable hydrogels. Likewise, digital light processing (DLP) printing technology can be employed to fabricate GelMA-based tissue engineering scaffolds with specific mechanical properties. These properties can range from less than 10 kPa to more than 30 kPa, and the scaffolds are produced by adjusting different polymer concentrations, substitution rates, and initiator concentrations[51].

GelMA has both the bioactivity of gelatin and the photocrosslinking property. The rheological and degradation properties of the ink can be controlled by adjusting the degree of methacrylation. The printed bone scaffolds can support the proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. When loading drugs (such as anticancer drugs for postoperative repair of bone cancer), it can achieve local sustained release and synergistically promote bone repair and tumor inhibition. However, the mechanical strength of GelMA depends on the crosslinking degree, and excessive crosslinking can easily lead to increased brittleness of the scaffold.

Analogous to the conventional hydrogel system, the primary shortcoming of pure GelMA lies in its inadequate mechanical characteristics, which limit its application in BTE[62,64]. Nevertheless, the incorporation of diverse nanomaterials and their physical or covalent association with GelMA imparts superior mechanical and biological properties to hydrogel scaffolds[62]. Among these nanomaterials, mineral-based nanoparticles, such as hydroxyapatite and nanoclay, remain the most widely used in BTE.

Hydroxyapatite, being the most crucial inorganic constituent of bone, can enhance the osteogenic potential of GelMA scaffolds. Zuo and colleagues demonstrated that the compression modulus of hydrogels rose from 13 kPa for pure GelMA to 23 kPa for GelMA containing 2% (w/v) hydroxyapatite. Additionally, following a 7-day co-culture of different scaffolds with cells, the expression of the majority of osteogenic genes in the scaffolds containing hydroxyapatite showed an increase[62].

Gao et al. devised a printing strategy for nanoclay/GelMA composite hydrogels. They segmented the printing process into three phases: extrusion, deposition, and fusion. After systematically investigating the impact of manufacturing process parameters on the support forming process, they also specified the particular printing parameters[53].

Furthermore, Greeshma et al. formulated a GelMA-based bioink using autologous bone particles (BPs). After conducting a series of tests, such as rheological analysis and mechanical performance assessment, they determined the appropriate printing parameters. Ultimately, through observing the proliferation, migration, and osteogenic differentiation capabilities of cells within the scaffolds, it was discovered that 3D-printed GelMA/BP composite scaffolds could effectively facilitate bone regeneration[54].

4.1.2 Collagen-based polymers

Collagen is the main component of the natural extracellular matrix. Collagen-based materials have excellent biocompatibility and can promote cell adhesion and proliferation. After photocrosslinking modification (e.g., the introduction of photosensitive groups), the curing behavior of the ink can be controlled. In the construction of bone scaffolds, the scaffolds printed with collagen-based bioinks can simulate the microenvironment of the natural bone matrix and guide mesenchymal stem cells to differentiate into osteoblasts. However, there are problems such as low mechanical strength and excessively fast enzymatic degradation. Therefore, it is often necessary to compound collagen with other materials for optimization.

To address these issues, researchers have explored various composite strategies. For instance, blending collagen with synthetic PLA or PCL can significantly enhance the mechanical properties of the scaffolds while maintaining their biocompatibility. Additionally, incorporating inorganic components, such as hydroxyapatite or bioactive glass particles, into collagen-based bioinks can further enhance the osteoinductive capacity and mechanical stability of printed bone scaffolds. These composite materials not only overcome the limitations of pure collagen-based bioinks but also provide a more favorable microenvironment for bone tissue regeneration.

Silk fibroin, one of the toughest fibrous proteins found in nature, is characterized by outstanding biocompatibility and biodegradability. Through a chemical modification process known as methacrylation, it can be transformed into SilMA, which is suitable for DLP printing technology[59]. Kim et al.[60]., introduced a method to create an efficient SilMA-based bioink. This bioink not only exhibits favorable printability but also demonstrates good cytocompatibility. Using DLP printing technology, a 30% SilMA solution was employed to fabricate intricate models, including tissue-engineered scaffolds, brain replicas, and ear structures. These models possess superior mechanical properties compared to regular hydrogels. For instance, when subjected to pressure and deformed, the brain and ear models can revert to their initial shapes. Moreover, NIH-3T3 fibroblasts were incorporated into the bioink for DLP printing, and the printed constructs were cultured in an in vitro environment. Regardless of the SilMA concentration, the majority of cells remain viable for up to 14 days. These characteristics of the prepared hydrogels are crucial for their application in BTE.

SilMA is suitable not only for standalone use in DLP printing but also for blending with other substances to formulate bioinks. Bandyopadhyay and colleagues combined varying concentrations of SilMA and poly (ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA), along with chondrocyte incorporation, to fabricate three-dimensional bioprinted osteochondral scaffolds. These scaffolds had a porous internal structure and were biodegradable. When chondrocytes were cultured on the scaffolds, an elevated secretion of cartilage-related proteins was detectable. These characteristics imply that the SilMA-PEGDA combination holds great promise for applications in cartilage regeneration and bone tissue engineering.

4.1.3 Hyaluronic acid

Hyaluronic acid (HA) is a naturally occurring linear polysaccharide composed of repeating disaccharide units (D-glucuronic acid and N-acetylglucosamine). It is widely distributed in the ECM, skin, synovial fluid, and vitreous humor, making it an ideal biomaterial for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. It has excellent properties, such as exceptional hydrophilicity and water retention, remarkable biocompatibility, bioactivity, and biodegradability. Moreover, it can be degraded in vivo by hyaluronidase, with no immunogenicity, and it regulates cell migration, proliferation, and differentiation through interactions with cell surface receptors (e.g., CD44, RHAMM). However, its broad application is limited by its poor mechanical properties and rapid degradation, necessitating chemical modifications to enhance stability.

Hyaluronic acid, much like gelatin, is plentiful in the extracellular matrix of bone and offers mechanical support. Through modification with methacrylate groups, HA can be transformed into HAMA, which is then bestowed with photocrosslinking capabilities. This modification enhances its printability and stiffness while still retaining excellent biocompatibility[49]. Poldevaart and colleagues showed that mesenchymal stem cells derived from human bone marrow could survive for 21 days and undergo osteogenic differentiation within 3D-printed HAMA scaffolds. While the efficacy of these scaffolds in animal models remains unproven, it has been reported that 3D-printed HAMA scaffolds may present a viable approach in bone tissue engineering[47]. Moreover,

HAMA was obtained through the reaction between HA and MA under alkaline conditions, in which methacryloyl groups were grafted onto HA’s hydroxyl (-OH) or carboxyl (-COOH) groups. The degree of substitution (DS, typically 10% - 50%) is controlled by adjusting the MA concentration. It forms covalent networks under UV light (365-405 nm) with photoinitiators (e.g., LAP), yielding tunable moduli

Although HAMA exhibits favorable biocompatibility, it is frequently combined with other substances, such as polymers, in bone tissue engineering . This is due to its lack of the mechanical characteristics necessary for bioprinting[56]. Cristina and colleagues blended HAMA, alginate, and PLA to create a 3D-printable hydrogel scaffold. This scaffold is anticipated to facilitate bone tissue regeneration via endochondral osteogenesis. Moreover, it possesses excellent mechanical properties, including printability, gel-forming capacity, rigidity, and satisfactory degradability[57].

4.1.4 Chitosan-based polymers

Chitosan has good biocompatibility and antibacterial properties. Photocrosslinkable chitosan bioink can be cured through Schiff base reaction, photo-initiated graft polymerization, etc. The constructed bone scaffolds have a pore structure that is conducive to nutrient transfer and cell colonization, and they can also load growth factors (such as bone morphogenetic protein -2) to promote bone repair synergistically. However, the printing accuracy of pure chitosan ink is affected by the rheological properties, making it necessary to adjust the concentration and add thickeners for improvement[65].

In addition, chitosan can be combined with other materials to form composite bioinks. For example, when combined with gelatin, the composite bioink not only inherits chitosan’s antibacterial properties but also improves mechanical properties and printability. This composite bioink can be used to fabricate more complex and precise three-dimensional structures, which is beneficial for tissue engineering applications. Moreover, the combination of chitosan with synthetic polymers such as poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) can also enhance the performance of the resulting scaffolds. The PLGA provides good mechanical strength and degradation characteristics, while chitosan contributes its biological activity, together creating a scaffold with both structural integrity and biofunctionality.

4.2 Synthetic polymers

Despite their favorable biodegradability and biocompatibility, natural polymers are predominantly used as additives or components in BTE. This is primarily due to the fact that their mechanical properties fall short of the typical strength of cancellous bone, which is greater than 100 MPa[56,66]. Consequently, in BTE, synthetic polymers with enhanced compressive strength are frequently utilized as the primary material for scaffolds. These synthetic polymers are typically combined with natural polymers that possess outstanding bone - inducing properties to fulfill the requirements of structural and functional biomimicry[67]. Currently, the synthetic polymers that are suitable for 3D printing mainly consist of PEGDA[68-70], poly (propylene fumarate) (PPF)[71-73], and pluronic F127 diacrylate (F127DA)[74-77].

4.2.1 Poly (ethylene glycol) diacrylate

PEGDA is a typical synthetic photosensitive polymer with strong hydrophilicity and good biocompatibility. The photocrosslinking reaction is fast and controllable, enabling accurate shaping of the complex structure of bone scaffolds. Its mechanical properties can be adjusted by the molecular chain length and crosslinking degree to adapt to the different stress requirements of bone tissue. However, PEGDA lacks bioactive sites, and it is often necessary to load biomolecules (such as RGD peptides) or bioceramics to enhance cell adhesion and osteoinductivity.

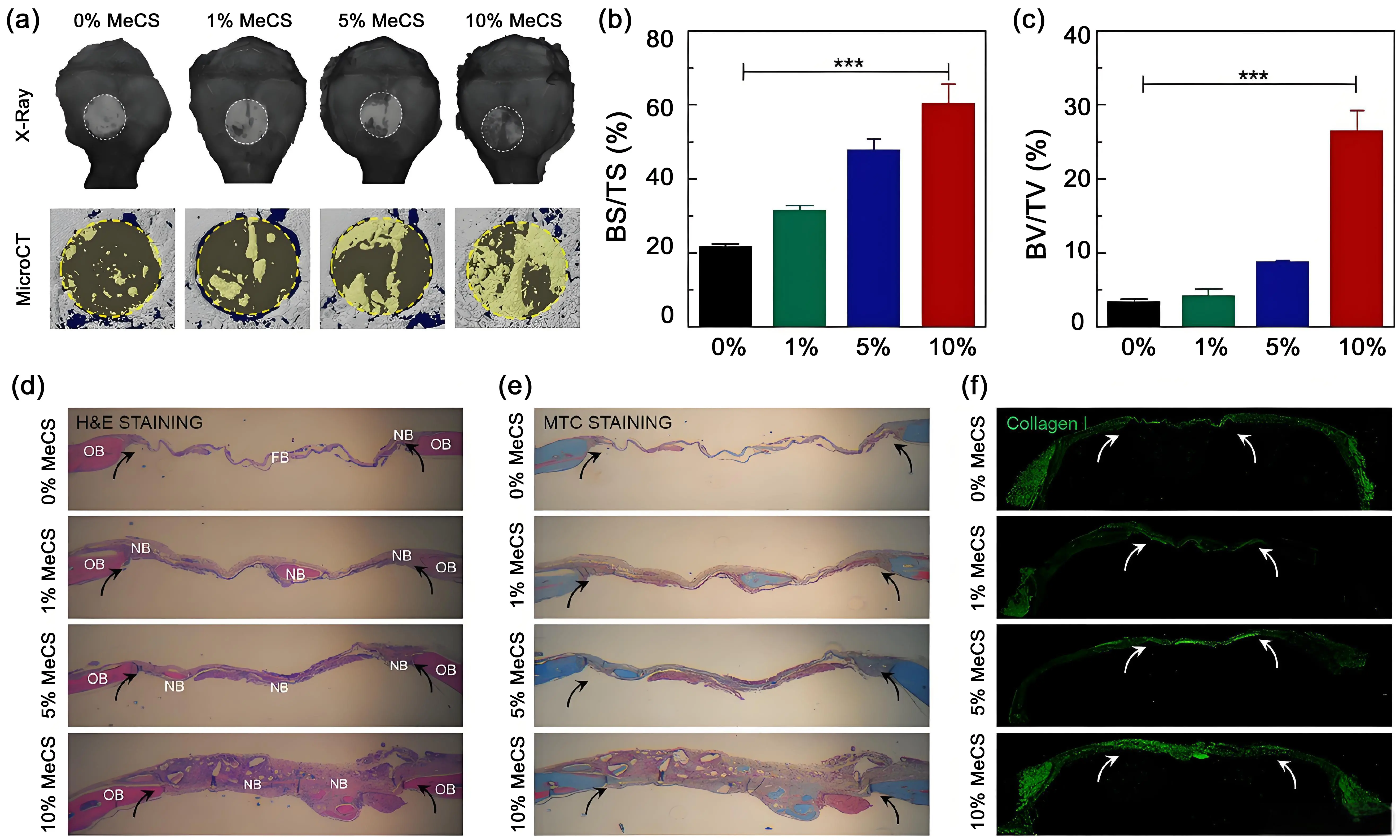

PEG, sanctioned by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for a wide array of biomedical uses, demonstrates excellent biocompatibility and scarcely any immunogenicity[78]. PEG is modified with alkenyl groups, and PEGDA with photo-crosslinking characteristics is generated. This PEGDA has low viscosity and high solubility, rendering it a prime biomaterial for 3D bioprinting[70]. By altering the molecular weight or concentration of PEGDA, scaffolds with specific physical and mechanical attributes can be fabricated. Moreover, the degradation rate of these scaffolds can be regulated by modifying the degree of polymerization[79]. Kim and colleagues created 3D-printed hydrogel scaffolds composed of PEGDA and chondroitin sulfate. These scaffolds can trigger the osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in an in vitro setting. PEGDA contributed to the good printability of the scaffolds. Meanwhile, chondroitin sulfate, through the negative charge of its sulfate group, combined with cations such as calcium and phosphorus to create a microenvironment that favored osteogenesis. After being implanted into a critical-sized defect in the rat skull, this composite hydrogel scaffold significantly promoted bone regeneration (Figure 3)[80].

Figure 3. In vivo bone regeneration. The hydrogels ladened with cells were transplanted into a 4 mm-diameter defect of the mouse skull. (a-c) X-ray and micro-CT analysis of bone repair in vivo; (d-f) Histological analysis with H & E, MTC, and collagen I staining[81]. MeCS: methacrylated chondroitin sulfate; BS: bone surface; TS: tissue surface;

Moreover, blending minerals with PEGDA presents an excellent option for enhancing both mechanical and biological characteristics. Gaharwar and colleagues[82] incorporated hydroxyapatite nanoparticles into bioinks to introduce additional hydroxyapatite into hydrogel scaffolds while still retaining the 3D printing functionality. The findings indicated that when less than 15% of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles were added, the printing ability of the hydrogel scaffold was not notably altered. However, the mechanical properties were enhanced. Specifically, the tensile modulus increased threefold, the fracture strength rose eightfold, and the toughness improved tenfold. Additionally, as the concentration of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles increased, the swelling degree decreased, yet the shape of the scaffold remained constant[68].

Despite the numerous benefits of PEGDA, it typically exhibits inelasticity and brittleness. This characteristic renders it more suitable for being utilized in conjunction with other materials rather than being employed independently for BTE[83]. Another important synthetic polymer in this category is PCL. PCL is a biodegradable polyester with excellent mechanical properties, good biocompatibility, and ease of processing. It has a relatively slow degradation rate, which allows for sustained release of drugs or growth factors in tissue engineering applications. PCL scaffolds can be fabricated through various techniques, such as electrospinning, 3D printing, and solvent casting, to create porous structures that mimic the extracellular matrix of bone tissue. Nevertheless, like PEGDA, PCL also lacks inherent bioactivity, and surface modifications or composite strategies are often employed to enhance its osteoconductivity and cell-binding properties.

4.2.2 Polypropylene fiber

PPF, a biodegradable polymer, undergoes degradation via the hydrolysis of its ester linkages. The resulting degradation products are fumaric acid and propylene glycol, both of which are non-toxic. In the past few decades, PPF has been the subject of in-depth research. This is mainly because of its highly promising biocompatibility and the ability to have its mechanical characteristics regulated[84,85]. PPF is capable of being dissolved in the solvent N,N-dimethylformamide and undergoes crosslinking when a photoinitiator, bis (2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl)-phenylphosphineoxide, is present. In 1996, PPF started to be utilized in BTE. It continued to gain widespread application in BTE until 2003. In that year, Cooke and colleagues fabricated tissue engineering scaffolds via the stereolithography apparatus (SLA) printing method to repair bone defects, further solidifying PPF’s role in the field of BTE[71,84].

A matter of concern regarding the application of polymers in BTE is the degradation period. To regulate the degradation speed of the scaffold, Nettleton and colleagues[73] bioinks were crafted using prepared PPF with distinct relative molecular weights of 1,000 and 1,900 Da. These bioinks were then printed via the DLP technique and subsequently implanted into cranial defects of rats. The objective was to investigate their degradation characteristics and bone-regeneration capabilities.

After 4 weeks, the 1,000 Da formulation of PPF degraded faster than the 1,900 Da formulation. This more rapid degradation led to greater bone tissue growing into the defect site. However, by the 12-week mark, the quantity of regenerated bone in the case of the low-molecular-mass PPF was comparable to that of the high-molecular-mass PPF. In conclusion, an appropriate degradation rate is of utmost importance for the effective repair of bone defects.

Moreover, PPF can serve as a vehicle for cells or factors[72,86]. Cells have the potential to attach, multiply, and undergo differentiation on the scaffold. Moreover, the scaffold made from PPF allows for the gradual release of growth factors such as transforming growth factor-beta and bone BMP-2. Possessing two crucial features of biocompatibility and biodegradability, which are essential for tissue engineering, PPF-based scaffolds can be fabricated using a SLA or DLP printing. These scaffolds have been extensively utilized in BTE.

4.2.3 Polyether F127 diacrylate

F127DA, which possesses both temperature-sensitive and photosensitive characteristics, is capable of undergoing a reversible transformation between the liquid and solid states within the temperature range from room temperature to 37 ℃. Moreover, upon being stimulated by photoinitiators, it can cross-link to form a stable hydrogel at room temperature. Owing to its low swelling ratio, high strength, fatigue endurance, and suitable elastic modulus, F127DA finds extensive applications in tissue engineering, as noted by Shen et al.[74]. Microfluidic chips were fabricated leveraging the anti-fatigue and anti-swelling characteristics of F127DA. Subsequently, the interior of these chips was seeded with Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells. In perfusion culture, this seeding aimed to stimulate endothelial function. Moreover, vascular spheroids were also prepared. These spheroids are anticipated to find applications in BTE to facilitate vascularized regeneration[76].

Although F127DA offers numerous benefits, it is not suitable for cell adhesion on its own because it lacks cell adhesion sites. As a result, composites based on F127DA are more advantageous for cell adhesion. This was reported by Ren et al.[75] who incorporated 1.5% HAMA into the F127DA bioink. This addition augmented the bioactivity of the scaffold while still preserving its mechanical properties. After the scaffold was implanted into the defect sites of the rabbit thyroid cartilage, favorable therapeutic outcomes were noted. Moreover, Wang et al.[87] also combined sodium alginate with F127DA. A shape-memory hydrogel with excellent biocompatibility was fabricated via 3D printing. This hydrogel holds great promise for drug-delivery applications.

Currently, F127DA is scarcely employed in BTE. This limited usage might be attributed to its subpar cell adhesion properties. While certain researchers have addressed this issue by modifying it with RGD peptides[88], further investigations are required to enhance the utility of F127DA in bone regeneration.

Certain polymers, including PCL and PLA, are more commonly used in the preparation of scaffolds via FDM printing than via DLP or SLA. Moreover, specific ceramics, such as hydroxyapatite (HAp) and tricalcium phosphate (TCP) powders, can be printed via DLP technology. However, since these ceramics lack inherent photocrosslinking properties, a photosensitive resin is required. First, the powder is dispersed within a photopolymer resin. Subsequently, the mixture is printed. After that, the organics in the resulting mold are removed, and the mold is sintered at 600 °C to acquire the scaffold[89].

4.3 Photocurable-bioink filling materials

In biomedical applications, in addition to the aforementioned photocurable organic matrix materials, several biologically active inorganic materials can be incorporated into the photocuring system as functional fillers to regulate the biological and mechanical properties of the composite materials. This type of inorganic filler can construct a biomimetic microenvironment by synergistically interacting with a photosensitive polymer matrix, thereby better simulating the multi-level structure and function of natural bone tissue. For example, the introduction of nanoscale inorganic fillers can enhance cell adhesion and proliferation, endow the material with controllable degradation kinetics and bone-conductive ability, and provide a key material basis for constructing

4.3.1 Hydroxyapatite

HAp has a chemical composition similar to that of natural bone minerals, with high bioactivity and good osteoconductivity, and is commonly used as an inorganic filler for bone scaffolds. In photocrosslinkable bioinks, HAp particles can enhance the mechanical properties (such as compressive strength and elastic modulus) of scaffolds, provide calcium and phosphorus ions, and promote the formation of mineralized nodules by osteoblasts. However, a pure HAp-based scaffold is brittle. When compounded with polymers, it is necessary to optimize the dispersibility to avoid agglomeration, thus affecting the printing effect and scaffold performance[90].

To improve the dispersibility of HA in photocrosslinkable bioinks, surface modification methods are often used. For example, HA particles can be coated with polymers having functional groups that can form chemical bonds with both HA and the bioink matrix. This not only enhances the compatibility between HA and the polymer matrix but also improves the overall mechanical properties and biological performance of the scaffolds. Additionally, adjusting the particle size and shape of HA can also influence its dispersibility and the subsequent properties of the scaffolds. Smaller, more uniformly shaped HA particles tend to disperse more evenly in the bioink, resulting in more homogeneous scaffolds with improved mechanical integrity and biological activity.

Moreover, the incorporation of HA into photocrosslinkable bioinks can be tailored to achieve specific biological functions. For instance, by controlling the release rates of calcium and phosphorus ions from HA particles, it is possible to regulate osteoblast differentiation and proliferation, thereby enhancing bone regeneration. Furthermore, combining HA with other bioactive molecules, such as growth factors or drugs, can create multifunctional scaffolds that not only support bone formation but also deliver therapeutic agents to the injury site. This approach opens up new avenues for the development of advanced bone tissue engineering scaffolds with enhanced biological and mechanical properties[91].

4.3.2 Tricalcium phosphate

TCP is degradable and releases calcium and phosphorus ions during degradation, which participate in new bone mineralization. The introduction of TCP into photocrosslinkable bioinks can regulate the degradation rate of scaffolds to match the bone repair cycle. Its porous structure is conducive to cell infiltration and blood vessel ingrowth. In the repair of bone defects caused by bone cancer, it can also load chemotherapeutic drugs to achieve local controlled release and inhibit tumor recurrence. However, the mechanical support of TCP is weaker than that of HAp, and the ratio with polymers needs to be reasonably designed[92].

In clinical applications, the combination of TCP with other biocompatible materials can effectively compensate for its deficiency in mechanical strength. For instance, blending TCP with certain synthetic polymers can significantly enhance the overall mechanical properties of the scaffold, making it more suitable for load-bearing bone repair. Moreover, the surface modification of TCP particles can further improve their compatibility with bioinks and enhance cell adhesion and proliferation on the scaffold surface. Recent studies have also focused on optimizing the particle size and morphology of TCP to achieve better biological performance and degradation characteristics. By fine-tuning these parameters, researchers aim to develop more effective photocurable bioinks for bone tissue engineering applications.

In addition to its application in load-bearing bone repair, TCP-based photocurable bioinks have shown great potential in other areas of bone tissue engineering. For example, they can be used in the fabrication of personalized bone grafts with complex geometries, which are difficult to achieve by traditional methods. The ability to precisely control the degradation rate and mechanical properties of the scaffolds through the adjustment of TCP content and polymer ratio allows for tailored solutions to meet specific clinical needs. Furthermore, the incorporation of TCP into bioinks can also promote the osteogenic differentiation of stem cells, thereby accelerating the bone regeneration process. Through ongoing research and development, TCP-based photocurable bioinks are expected to play a more important role in the field of bone tissue engineering, offering new possibilities for the treatment of bone defects and related diseases[93].

4.3.3 Bioactive glass

Bioactive glass (BG) can stimulate the expression of genes related to bone regeneration, promote the proliferation of osteoblasts and the secretion of bone matrix, and also has certain antibacterial properties (inhibiting the risk of bone infection). In photocrosslinkable bioinks, BG nanoparticles can improve the rheological properties of the ink and enhance the bioactivity of the scaffold. However, the pH change that arises from BG degradation products may affect the cell microenvironment, and the amount added needs to be precisely controlled[94].

Moreover, the incorporation of BG nanoparticles into photocrosslinkable bioinks requires careful consideration of the dispersion uniformity. Poor dispersion can lead to agglomeration, which may not only compromise the mechanical properties of the printed scaffold but also affect the biological performance. To address this issue, surface modification techniques for BG nanoparticles can be employed to enhance their compatibility with the bioink matrix. Additionally, the interaction between BG and other components in the bioink, such as polymers and growth factors, should be thoroughly investigated to ensure the stability and functionality of the composite system.

4.3.4 Silica-based materials

Silica-based materials (such as mesoporous silica) have a high specific surface area and controllable pore size, and can be used as drug carriers to load growth factors and anticancer drugs. Combined with photocrosslinkable bioinks, they can not only assist in regulating ink curing (e.g., providing nucleation sites to accelerate crosslinking) but also achieve sustained release of active substances, with potential for synergy in bone repair and bone cancer treatment. However, their biosafety needs to be considered, and the impact of long-term degradation products on tissues still needs in-depth research[95].

5. Application in Bone Tissue Engineering

5.1 Construction of bone repair scaffolds

Polymer-inorganic composite bioinks can integrate the advantages of both: polymers provide the plasticity and biocompatibility of scaffolds, while inorganic materials provide mechanical support and osteoinductivity. For example, scaffolds printed with the GelMA/HA composite ink, after photocrosslinking and curing, exhibit porosity and mechanical properties suitable for bone tissue requirements. In vitro cell experiments show high expression of osteogenic genes (such as Runx2 and OCN). When implanted in animal bone defect models in vivo, the amount of new bone formation was significantly higher than that of scaffolds made of a single material[96].

As a result, a novel approach of fabricating bilayered scaffolds for osteochondral tissue engineering has arisen to address osteochondral defects. Certain researchers have independently developed cartilage scaffolds and bone scaffolds, and subsequently joined these two types of scaffolds using sutures, biological sealants, or biological adhesives. As a consequence, there is a distinct boundary between the bone layer and the cartilage layer. Moreover, cells are unable to cross this boundary to generate calcified cartilage, leading to an unstable bone-cartilage interface[97].

It is probable that new bone tissues will grow into the cartilage region of the osteochondral defect, and long-term stratification might occur. As research on bilayered scaffolds progresses, certain intrinsic drawbacks in osteochondral repair have become more prominent. Subsequently, a clear demarcation forms between the cartilage and bone layers, leading to uneven differentiation of stem cells at the cartilage-bone junction or giving rise to a distinct band-like zone. Ultimately, this leads to the failure of bone and cartilage integration. Due to the uniqueness of bone and cartilage structures, only a suitable osteochondral scaffold can promote the proliferation and differentiation of seed cells into osteochondral tissue within the body, thus accomplishing the osteochondral repair.

5.2 Synergistic repair in bone cancer treatment

For bone defects after bone cancer resection, composite bioink scaffolds can load chemotherapeutic drugs (such as doxorubicin) and osteogenic induction factors. Polymers (such as PEGDA) regulate the sustained release kinetics of drugs, while inorganic materials (such as TCP) maintain the scaffold structure and ion supply, thereby achieving the dual functions of inhibiting tumor recurrence and promoting bone repair. In preclinical studies, such scaffolds can effectively reduce tumor residues and accelerate bone defect reconstruction in mouse bone cancer models, but problems such as optimizing drug loading and long-term toxicology still need to be addressed.

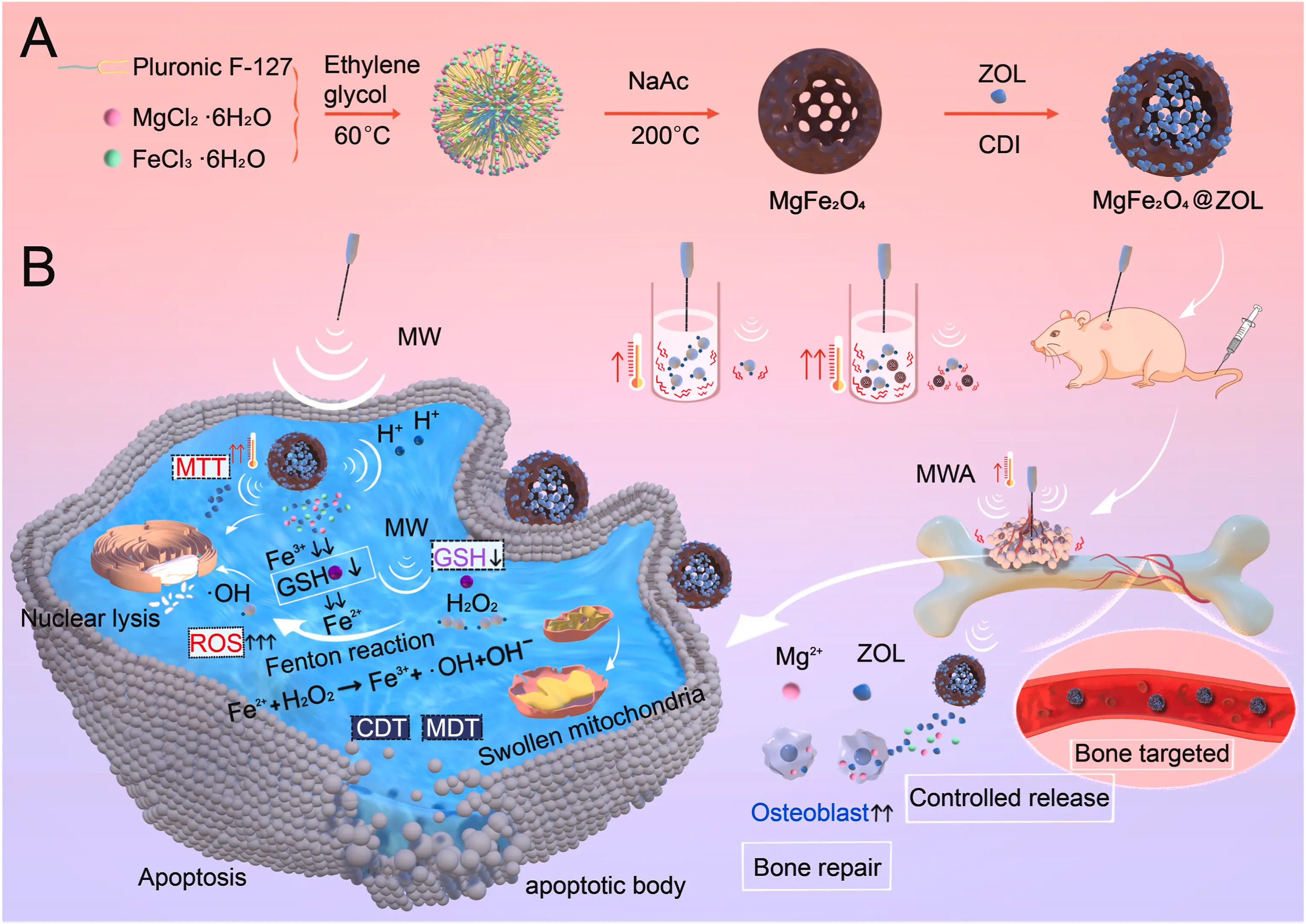

Once bone metastasis occurs in lung cancer, treatment efficacy can be greatly reduced. Current mainstream treatments are focused on inhibiting cancer cell growth and preventing bone destruction. Microwave ablation (MWA) has been used to treat bone tumors. However, MWA may damage the surrounding normal tissues. Therefore, it could be beneficial to develop a nanocarrier combined with microwave treatment to treat bone metastasis. Herein, a microwave-responsive nanoplatform (MgFeO@ZOL) was constructed. MgFeO@ZOL NPs release the cargos of Fe, Mg, and zoledronic acid (ZOL) in the acidic tumor microenvironment. Fe can deplete intracellular glutathione (GSH) and catalyze HO to generate •OH, resulting in chemodynamic therapy (CDT). In addition, the microwave can significantly enhance the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), thereby enabling the effective implementation of microwave dynamic therapy (MDT). Moreover, Mg and ZOL promote osteoblast differentiation. In addition, MgFeO@ZOL NPs could target and selectively heat tumor tissue, thereby enhancing the efficacy of microwave thermal therapy (MTT). Both in vitro and in vivo experiments revealed that synergistic targeting, GSH depletion-enhanced CDT, MDT, and selective MTT exhibited significant antitumor efficacy and bone repair. This multimodal combination therapy provides a promising strategy for the treatment of bone metastasis in lung cancer patients (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Schematic illustration of the microwave and MgFe2O4@ZOL NPs used in synergistic tumor therapy. (A) The synthesis process of MgFe2O4@ZOL NPs; (B) Schematic diagram of synergistic therapy involving targeting, CDT, MDT, and selective-MTT, and bone repair for bone metastasis[98]. ZOL: zoledronic acid; CDI: 1,1′-carbonyldiimidazole; MW: microwave; MWA: microwave ablation; MTT: mitochondrial targeting therapy; MDT: magnetic dynamic therapy; CDT: chemodynamic therapy

6. Challenges and Prospects

6.1 Current challenges: Specific bottlenecks and their implications

The development of polymer-inorganic composite bioinks for bone tissue engineering is progressing, yet it remains constrained by several interconnected and specific bottlenecks that hinder clinical translation.

Material Compatibility and Interfacial Failure: The core issue is not merely “poor interface bonding” but a fundamental physicochemical mismatch at the polymer-inorganic (e.g., hydroxyapatite, bioactive glass) interface. This leads to weak stress transfer, delamination under physiological loading, and unpredictable localized degradation. The resultant microcracks become foci for premature mechanical failure and inconsistent biological response, ultimately deteriorating the scaffold’s structural integrity and osteoconductive function.

Printing Accuracy for Hierarchical Biomimicry: The challenge extends beyond “difficulty in precise forming”. It involves the multiscale reproduction of bone’s architecture—from macroporous networks for vascular invasion to micro- and nanotopographical cues for cell differentiation. Conventional extrusion-based 3D printing struggles to control macro-geometry and micro-surface features simultaneously. Furthermore, the incorporation of inorganic particles often alters bioink rheology, leading to nozzle clogging, strand fusion, and loss of fine architectural details, limiting the replication of trabecular or osteon-like structures.

Dynamic Mismatch in Degradation-Regeneration Kinetics: The problem of “rate mismatch” is a spatiotemporal coordination challenge. Most composite scaffolds exhibit degradation profiles (hydrolytic/enzymatic) that are either too rapid, causing loss of mechanical support before new bone matures, or too slow, creating a physical barrier to tissue ingrowth and remodeling. This asynchrony can lead to implant failure, fibrous encapsulation, or incomplete ossification. The added complexity arises from the differing degradation mechanisms of the polymeric matrix and the inorganic phase, which are rarely concerted.

Many current composites are primarily structural, lacking advanced functionalities such as stimuli-responsiveness, controlled factor delivery, or electrical/magnetic activity to guide regeneration beyond passive support actively.

6.2 Targeted breakthrough approaches and cutting-edge prospects

To transition from “repair and replacement” to “precise regeneration”, future research must address the above bottlenecks with integrated, innovative strategies.

Advanced Interfacial Engineering via Bioinspired Design: Moving beyond simple blending, next-generation strategies will focus on molecular-level interface design.

Bioinspired Coupling Agents: Developing peptides or polydopamine-like linkers that mimic marine adhesive proteins or biomineralization processes (e.g., using silicatein-inspired motifs) to create covalent or strong coordinative bonds at the interface.

Core-Shell and In Situ Precipitation Strategies: Pre-coating inorganic particles with a thin polymer layer (core-shell) or precipitating nano-inorganic phases directly within the polymer network in situ during ink preparation. This ensures perfect wetting, uniform dispersion, and dramatically enhanced interfacial adhesion and stress distribution.

Multiscale Printing and Intelligent Photocrosslinking Regulation: Multiscale Hybrid Printing: Integrating different printing modalities—such as combining extrusion printing for macroscopic shape with electrohydrodynamic printing or melt electrowriting for depositing micro/nanofibers within the same scaffold. This creates hierarchically ordered environments for cells.

Intelligent Photocrosslinking: This involves using wavelength-selective or two-photonphotopolymerization. Wavelength-selective systems enable independent, sequential crosslinking of different ink components to form gradient or compartmentalized structures. Two-photon polymerization enables sub-micron resolution, allowing the direct fabrication of intricate surface textures and

Designing 4D and Functionally-Graded Bioinks for Synchronized Regeneration:

Spatiotemporal Programming: Developing 4D bioinks that change shape or stiffness over time in response to physiological cues (e.g., enzyme concentration, pH). This can be used to maintain porosity initially, then gradually compact to apply micromechanical stimuli for osteogenesis.

Degradation-Rate Tuning via Compositional Gradients: Creating functionally-graded composite inks with spatially varied polymer/inorganic ratios or polymer chemistries (e.g., lactide/glycolide ratios in PLGA). This allows the scaffold periphery to degrade more rapidly, facilitating initial cell infiltration, while the core degrades more slowly, providing prolonged load-bearing. Coupling this with real-time monitoring techniques (e.g., biodegradable microsensors, contrast agents for imaging) will enable non-invasive tracking of degradation and tissue formation.

Towards Multifunctional and “Active” Composite Bioinks: The future lies in moving from passive scaffolds to active, instructive platforms.

Multifunctional Composite Inks: Incorporating bioactive ions (Sr2+, Mg2+, Cu2+) into the inorganic phase, or blending polymers with conductive components (e.g., PEDOT: PSS, graphene oxide) to create inks that are osteogenic, angiogenic, and electroconductive. This supports not only osteogenesis but also vascularization and neural ingrowth for complex bone repair.

Cell-instructive and Drug-Eluting Systems: Designing bioinks where the inorganic particles themselves act as reservoirs for the controlled release of growth factors (e.g., BMP-2) or miRNAs, with release kinetics tied to their dissolution rate, achieving precise biological cue delivery aligned with healing stages.

6.3 Path to clinical translation

Addressing these challenges requires a convergent approach spanning materials science, advanced manufacturing, and developmental biology. Deepening preclinical research must involve long-term studies in large, critical-sized defect models that experience physiological load-bearing, with a focus on understanding the foreign body response, biodegradation byproducts, and the ultimate remodeling of the scaffold into mature, vascularized bone. By systematically targeting the specific bottlenecks of interface design, multiscale fabrication, dynamic synchronization, and functional complexity, polymer-inorganic composite bioinks can evolve into intelligent, patient-specific regenerative platforms. This will accelerate their journey from the laboratory bench to the clinical bedside, ultimately fulfilling the promise of precise and functional bone regeneration.

7. Conclusion

In conclusion, the application of polymers and inorganic materials in photocrosslinkable bioinks lays a foundation for the development of bone repair scaffolds. Although there are challenges, continuous innovation is expected to provide more effective engineering solutions for the treatment of bone defects, bone cancer, and other diseases. Moreover, the integration of interdisciplinary knowledge, such as biology, materials science, and engineering, will further promote the advancement of photocrosslinkable bioinks. Future research should focus on optimizing the properties of these materials, including their biocompatibility, mechanical strength, and degradation rates, to better meet clinical needs. By addressing these challenges, we can anticipate a brighter future for bone tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

Acknowledgments

Lei Nie acknowledges the Nanhu Scholars Program for young scholars at Xinyang Normal University (XYNU).

Authors contribution

Nie L: Funding acquisition, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, writing–review & editing.

Liang Y, Li J: Investigation, riting-original draft.

Ding P: Writing–review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

Lei Nie is an Editorial Board Member of BME Horizon. The other authors declare that they have no competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

We gratefully acknowledge the support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52405195).

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

References

-

1. Lee SS, Du X, Kim I, Ferguson SJ. Scaffolds for bone-tissue engineering. Matter. 2022;5(9):2722-2759.[DOI]

-

2. Mirkhalaf M, Men Y, Wang R, No Y, Zreiqat H. Personalized 3d printed bone scaffolds: A review. Acta Biomater. 2023;156:110-124.[DOI]

-

3. Mei Q, Rao J, Bei HP, Liu Y, Zhao X. 3D bioprinting photo-crosslinkable hydrogels for bone and cartilage repair. Int J Bioprint. 2021;7(3):367.[DOI]

-

4. Dobrisan MR, Lungu A, Ionita M. A review of the current state of the art in gelatin methacryloyl-based printing inks in bone tissue engineering. Virtual Phys Prototyp. 2024;19(1):e2378003.[DOI]

-

5. Feng P, Yang F, Jia J, Zhang J, Tan W, Shuai C. Mechanism and manufacturing of 4D printing: derived and beyond the combination of 3D printing and shape memory material. Int J Extrem Manuf. 2024;6(6):062011.[DOI]

-

6. Wan Z, Zhang P, Liu Y, Lv L, Zhou Y. Four-dimensional bioprinting: Current developments and applications in bone tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2020;101:26-42.[DOI]

-

7. Yang F, Ding W, Jia J, Shuai C, Feng P. 4D printing for bone implant: Progress, advantages and challenges. Prog Mater Sci. 2026;157:101591.[DOI]

-

8. Firipis K, Footner E, Boyd-Moss M, Dekiwadia C, Nisbet D, Kapsa RMI, et al. Biodesigned bioinks for 3D printing via divalent crosslinking of self-assembled peptide-polysaccharide hybrids. Mater Today Adv. 2022;14:100243.[DOI]

-

9. Kamaraj M, Sreevani G, Prabusankar G, Rath SN. Mechanically tunable photo-cross-linkable bioinks for osteogenic differentiation of MSCs in 3D bioprinted constructs. Mater Sci Eng C. 2021;131:112478.[DOI]

-

10. Liu S, Kilian D, Ahlfeld T, Hu Q, Gelinsky M. Egg white improves the biological properties of an alginate-methylcellulose bioink for 3D bioprinting of volumetric bone constructs. Biofabrication. 2023;15(2):025013.[DOI]

-

11. Mahmoud AH, Han Y, Dal-Fabbro R, Daghrery A, Xu J, Kaigler D, et al. Nanoscale β-TCP-Laden GelMA/PCL Composite Membrane for Guided Bone Regeneration. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2023;15(27):32121-32135.[DOI]

-

12. Jeon O, Lee YB, Hinton TJ, Feinberg AW, Alsberg E. Cryopreserved cell-laden alginate microgel bioink for 3D bioprinting of living tissues. Mater Today Chem. 2019;12:61-70.[DOI]

-

13. Ma J, Qin C, Wu J, Zhang H, Zhuang H, Zhang M, et al. 3D printing of strontium silicate microcylinder-containing multicellular biomaterial inks for vascularized skin regeneration. Adv Healthcare Mater. 2021;10(16):2100523.[DOI]

-

14. Rahaman KA, Mukim MSI, Hasan ML, Kim H, Pan CH, Kwon OS, et al. Protein to biomaterials: Unraveling the antiviral and proangiogenic activities of Ac-Tβ1-17 peptide, a thymosin β4 metabolite, and its implications in peptide-scaffold preparation. Bioact Mater. 2025;49:437-455.[DOI]

-

15. Li R, Zhao Y, Zheng Z, Liu Y, Song S, Song L, et al. Bioinks adapted for in situ bioprinting scenarios of defect sites: A review. RSC Adv. 2023;13(11):7153-7167.[DOI]

-

16. Ghorbani F, Ghalandari B, Khajehmohammadi M, Bakhtiary N, Tolabi H, Sahranavard M, et al. Photo-cross-linkable hyaluronic acid bioinks for bone and cartilage tissue engineering applications. Int Mater Rev. 2023;68(7):901-942.[DOI]

-

17. Han S, Kim CM, Jin S, Kim TY. Study of the process-induced cell damage in forced extrusion bioprinting. Biofabrication. 2021;13(3):035048.[DOI]

-

18. Khajehmohammadi M, Bakhtiary N, Davari N, Sarkari S, Tolabi H, Li D, et al. Bioprinting of cell-laden protein-based hydrogels: From cartilage to bone tissue engineering. Int J Bioprint. 2023;9(6):1089.[DOI]

-

19. Keriquel V, Oliveira H, Rémy M, Ziane S, Delmond S, Rousseau B, et al. In situ printing of mesenchymal stromal cells, by laser-assisted bioprinting, for in vivo bone regeneration applications. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1778.[DOI]

-

20. Zhang X, Zhang X, Li Y, Zhang Y. Applications of light-based 3D bioprinting and photoactive biomaterials for tissue engineering. Materials. 2023;16(23):7461.[DOI]

-

21. Chiticaru EA, Ioniță M. Commercially available bioinks and state-of-the-art lab-made formulations for bone tissue engineering: A comprehensive review. Mater Today Bio. 2024;29:101341.[DOI]

-

22. Bao B, Shi C, Zeng Q, Chen T, Xiao C, Jiang L, et al. Photocoupling of propagating radicals during polymerization realizes universal network strengthening. Nat Synth. 2025;4(12):1522-1533.[DOI]

-

23. Gu F, Neufeld R, Amsden B. Maintenance of vascular endothelial growth factor and potentially other therapeutic proteins bioactivity during a photo-initiated free radical cross-linking reaction forming biodegradable elastomers. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2007;66(1):21-27.[DOI]

-

24. Roose P, Vermoesen E, Van Vlierberghe S. Non-steady scaling model for the kinetics of the photo-induced free radical polymerization of crosslinking networks. Polym Chem. 2020;11(14):2475-2484.[DOI]

-

25. Sun G, Huang Y, Li D, Fan Q, Xu J, Shao J. Blue light induced photopolymerization and cross-linking kinetics of poly(acrylamide) hydrogels. Langmuir. 2020;36(39):11676-11684.[DOI]

-

26. Pereira RF, Barrias CC, Bártolo PJ, Granja PL. Cell-instructive pectin hydrogels crosslinked via thiol-norbornene photo-click chemistry for skin tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2018;66:282-293.[DOI]

-

27. Sánchez-Cid P, Romero A, Díaz MJ, de-Paz MV, Perez-Puyana V. Chitosan-based hydrogels obtained via photoinitiated click polymer ipn reaction. J Mol Liq. 2023;379:121735.[DOI]

-

28. Stuckhardt C, Wissing M, Studer A. Photo click reaction of acylsilanes with indoles. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2021;60(34):18605-18611.[DOI]

-

29. Wang G, Cao X, Dong H, Zeng L, Yu C, Chen X. A hyaluronic acid based injectable hydrogel formed via photo-crosslinking reaction and thermal-induced diels-alder reaction for cartilage tissue engineering. Polymers. 2018;10(9):949.[DOI]

-

30. Ameen S, Lee M, Kang MS, Cho JH, Kim B. Three-dimensional photo-cross-linkers for nondestructive photopatterning of electronic materials. Acc Mater Res. 2025;6(3):340-351.[DOI]

-

31. Huang R, Hua J, Ru M, Yu M, Wang L, Huang Y, et al. Superb silk hydrogels with high adaptability, bioactivity, and versatility enabled by photo-cross-linking. ACS Nano. 2024;18(23):15312-15325.[DOI]

-

32. Jeon O, Bouhadir KH, Mansour JM, Alsberg E. Photocrosslinked alginate hydrogels with tunable biodegradation rates and mechanical properties. Biomaterials. 2009;30(14):2724-2734.[DOI]

-

33. Kolahdoozan M, Rahimi T, Taghizadeh A, Aghaei H. Preparation of new hydrogels by visible light cross-linking of dextran methacrylate and poly(ethylene glycol)-maleic acid copolymer. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;227:1221-1233.[DOI]

-

34. Ma H, Peng Y, Zhang S, Zhang Y, Min P. Effects and progress of photo-crosslinking hydrogels in wound healing improvement. Gels. 2022;8(10):609.[DOI]

-

35. Nelson BR, Kirkpatrick BE, Miksch CE, Davidson MD, Skillin NP, Hach GK, et al. Photoinduced dithiolane crosslinking for multiresponsive dynamic hydrogels. Adv Mater. 2024;36(43):2211209.[DOI]

-

36. Lai Y, Xiao X, Huang Z, Duan H, Yang L, Yang Y, et al. Photocrosslinkable biomaterials for 3D bioprinting: Mechanisms, recent advances, and future prospects. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(23):12567.[DOI]

-

37. Maier AS, Mansi S, Halama K, Weingarten P, Mela P, Rieger B. Cytocompatible hydrogels with tunable mechanical strength and adjustable swelling properties through photo-cross-linking of poly(vinylphosphonates). ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2024;16(43):58135-58147.[DOI]

-

38. Mirani B, Stefanek E, Godau B, Hossein Dabiri SM, Akbari M. Microfluidic 3D printing of a photo-cross-linkable bioink using insights from computational modeling. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2021;7(7):3269-3280.[DOI]

-

39. (a) Elkhoury K, Patel D, Gupta N, Vijayavenkataraman S. Nanocomposite GelMA Bioinks: Toward Next‐Generation Multifunctional 3D‐Bioprinted Platforms. Small. 2025;21(45):e05968.[DOI](b) Ghosh RN, Thomas J, Janardanan A, Namboothiri PK, Peter M. An insight into synthesis, properties and applications of gelatin methacryloyl hydrogel for 3D bioprinting. Mater Adv. 2023;4(22):5496-529.[DOI]

-

40. (a) Jia W, Gungor-Ozkerim PS, Zhang YS, Yue K, Zhu K, Liu W, et al. Direct 3D bioprinting of perfusable vascular constructs using a blend bioink. Biomaterials. 2016;106:58-68.[DOI](b) Pourfaraj A, Najmoddin N, Behzadnasab M, Pedram MS, Pezeshki-Modaress M. Rapid continuous 3D printed multi-channel poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate/chitosan nerve guidance conduit: In vivo study. Int J Biol Macromol. 2025;321(Pt 4):146491.[DOI]

-

41. (a) Bencherif SA, Srinivasan A, Horkay F, Hollinger JO, Matyjaszewski K, Washburn NR. Influence of the degree of methacrylation on hyaluronic acid hydrogels properties. Biomaterials. 2008;29(12):1739-1749.[DOI](b) Spearman BS, Agrawal NK, Rubiano A, Simmons CS, Mobini S, Schmidt CE. Tunable methacrylated hyaluronic acid-based hydrogels as scaffolds for soft tissue engineering applications. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2020;108(2):279-291.[DOI]

-

42. (a) Geevarghese R, Żur-Pińska J, Parisi D, Włodarczyk-Biegun MK. A comprehensive protocol for hydrogel-based bioink design: balancing printability, stability, and biocompatibility. J Mater Chem B. 2025;13(42):13750-13768.[DOI](b) Zhou E, He P, Yang Z, Li C, Fang G, Wu J, et al. 3D-printed GelMA-Alginate microsphere scaffold with staged dual-growth factor release for enhanced bone regeneration. Mater Today Bio. 2025;35:102422.[DOI]

-

43. (a) Kim SH, Hong H, Ajiteru O, Sultan MT, Lee YJ, Lee JS, et al. 3D bioprinted silk fibroin hydrogels for tissue engineering. Nat Protoc. 2021;16(12):5484-5532.[DOI](b) Rajput M, Mondal P, Yadav P, Chatterjee K. Light-based 3D bioprinting of bone tissue scaffolds with tunable mechanical properties and architecture from photocurable silk fibroin. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;202:644-656.[DOI]

-

44. (a) Raja JK, Díaz GY, La Boucan FS, Perry MA, Tekumalla S, Dunuwilla TS, et al. Advances in decellularized extracellular matrix bioinks for regenerative medicine applications. Int J Bioprint. 2025;11(5):23-45.[DOI](b) Zhang CY, Fu CP, Li XY, Lu XC, Hu LG, Kankala RK, et al. Three-dimensional bioprinting of decellularized extracellular matrix-based bioinks for tissue engineering. Molecules. 2022;27(11)[DOI]

-

45. (a) Acosta-Cuevas JM, González-García J, García-Ramírez M, Pérez-Luna VH, Cisneros-López EO, González-Nuñez R, et al. Generation of photopolymerized microparticles based on pegda using microfluidic devices. Part 1. Micromachines. 2021;12(3):293.[DOI](b) Wilts EM, Gula A, Davis C, Chartrain N, Williams CB, Long TE. Vat photopolymerization of liquid, biodegradable plga-based oligomers as tissue scaffolds. Eur Polym J. 2020;130:109693.[DOI]

-

46. (a) Pezeshkian Z, Peyravian N, Najafloo R, MalekzadehKebria M, Hadi Mj, Valizadeh H, et al. Insights into cellulose nanocrystals-based bioinks for 3D bioprinting in regenerative medicine and tissue engineering: A review. Int J Biol Macromol. 2026;337:149409.[DOI](b) Yue H, Wang Y, Fernandes S, Vyas C, Bartolo P. Bioprinting of GelMA/PEGDA hybrid bioinks for SH-SY5Y cell encapsulation: Role of molecular weight and concentration. Macromol Biosci. 2025;25(6):e2400587.[DOI]

-

47. Poldervaart MT, Goversen B, de Ruijter M, Abbadessa A, Melchels FPW, Öner FC, et al. 3D bioprinting of methacrylated hyaluronic acid (MeHA) hydrogel with intrinsic osteogenicity. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):e0177628.[DOI]

-