Genping Huang, Department of Chemistry, School of Science Tianjin University, Tianjin 300072, China. E-mail: gphuang@tju.edu.cn

Xihe Bi, Department of Chemistry, Northeast Normal University, Changchun 130024, Jilin, China. E-mail: bixh507@nenu.edu.cn

Abstract

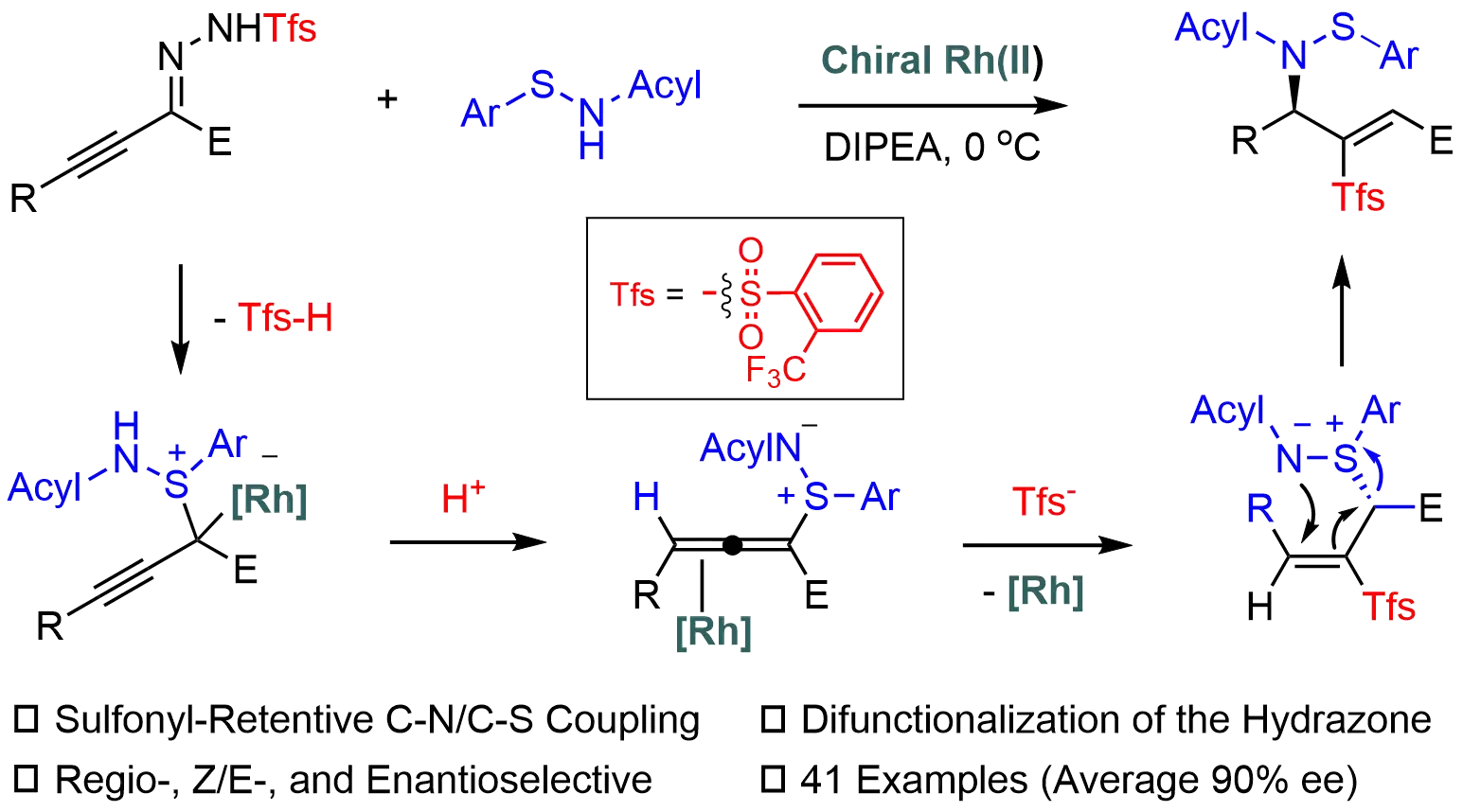

Sulfonylhydrazones are valuable carbene precursors in asymmetric synthesis; however, their use typically generates sulfinic acid, which is inevitably discarded as stoichiometric waste. In this work, the carbene chemistry and sulfur chemistry are integrated in Rh-catalyzed asymmetric sulfonyl retentive S,N-difunctionalization of alkynyl N-sulfonylhydrazones with sulfenamides. The sulfonyl group or the corresponding sulfinic acid is retained in a formal migration. This mild and efficient protocol allows for straightforward construction of enantioenriched sulfonyl-based allylic sulfenamides with excellent chemo-, E/Z-, and enantioselectivity, thereby offering a creative strategy for achieving more atom-economic transformations of carbene precursors. Mechanistic studies reveal a three-step process involving S-allenylation, hydrosulfonylation, and an aza-Mislow-Evans rearrangement, with the hydrosulfonylation step governing enantioselectivity.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

1. Introduction

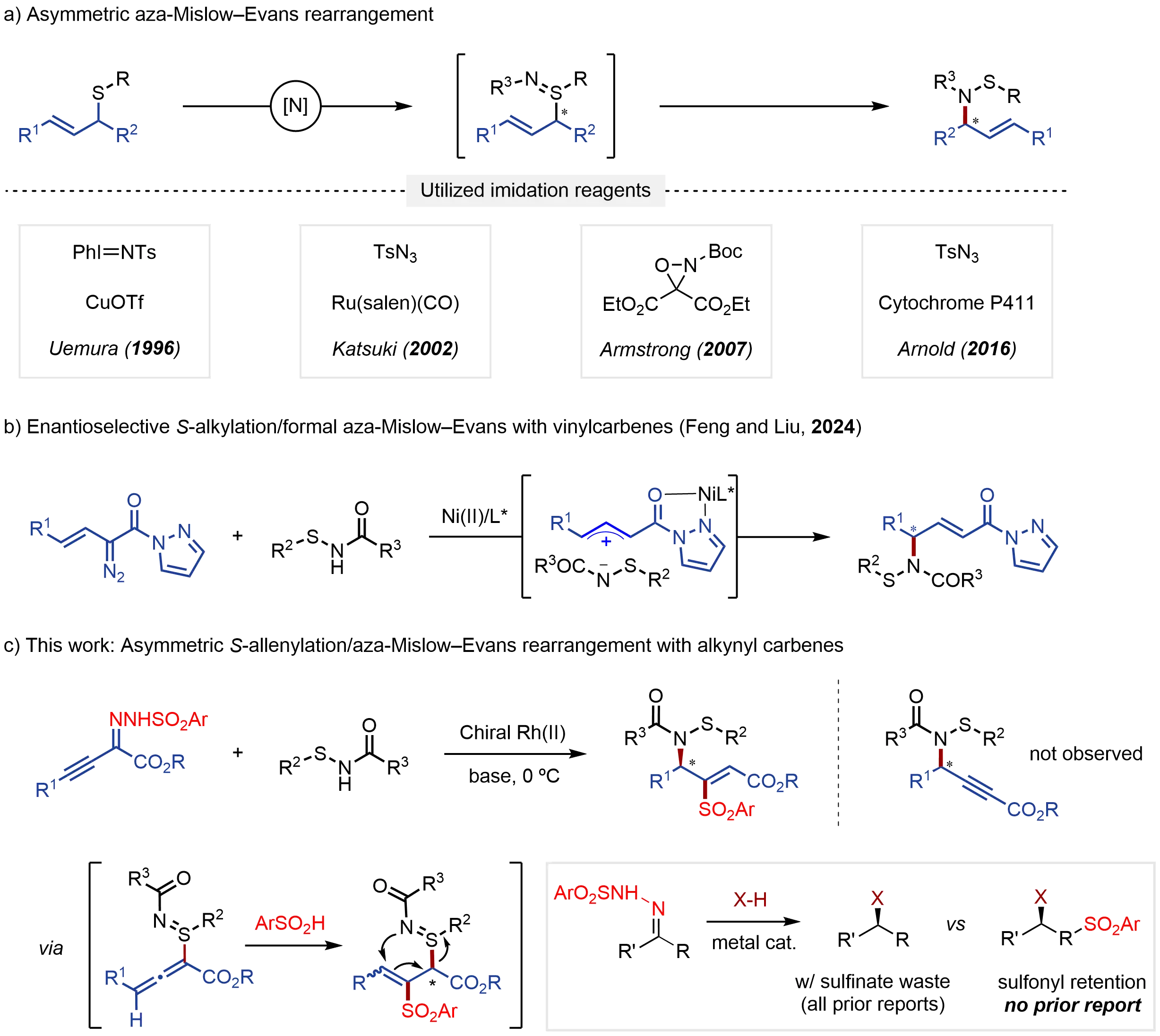

Sigmatropic rearrangements, involving the site-selective reorganization of molecular frameworks, represent a highly valuable class of transformations in synthetic chemistry due to their ability to create challenging chiral centers with high stereospecificity in complex structural motifs[1-7]. Given the rich reactivity of sulfinyl groups in chemical synthesis and pharmaceutical research[8-11], the sigmatropic rearrangement of allylic sulfur compounds has garnered significant interest over the years[12]. Among these, the Mislow-Evans rearrangement is a reversible [2,3]-sigmatropic shift converting allylic sulfoxides into allylic sulfenate esters, with equilibrium generally favoring sulfoxides. In the presence of thiophiles, however, S–O bond cleavage of the sulfenate esters enables the stereoselective formation of allylic alcohols[13-17]. This classical transformation has proven synthetically powerful in the stereoselective preparation of various bioactive molecules, drugs, and natural products[18-21]. Nevertheless, the related [2,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement of allylic sulfilimines, the nitrogen analogues of allylic sulfoxides, has received comparatively limited attention, despite its potential to produce synthetically and medicinally valuable allylic sulfenamides (Figure 1A)[22-24]. Challenger reported the first aza-Mislow-Evans rearrangement of allylic sulfilimines to allylic sulfenates in 1952[22], although its application remains limited due to the lack of effective methods for preparing enantioenriched allylic sulfilimine intermediates. To date, three strategies have been developed for their preparation. The first strategy involves the α-sulfenylation of aldehydes, followed by oxidative S-imidation using N-Boc-oxaziridine[25-29]. The second relies on asymmetric sulfimidation of achiral allylic sulfides using a bisoxazoline complex, a ruthenium-salen complex, or an enzyme as catalyst to generate metal nitrene species from [N-(p-toluenesulfonyl)imino]phenyliodinane (TsN=IPh) and tosyl azides[30-34]. However, these two strategies are of limited synthetic utility due to the involvement of dangerous imidation agents, multistep procedures, and narrow substrate scope. Recently, Feng and Liu described an elegant nickel-catalyzed asymmetric synthesis of allylic sulfenamides via a formal aza-Mislow-Evans rearrangement of allylic sulfilimines through loose ion pair intermediates, arising from in situ S-alkylation of sulfenamides[35-54] and hazardous vinyl α-diazo pyrazoleamides (Figure 1B)[55]. Despite these advancements, there remains a pressing need for mild and more efficient strategies to generate allylic sulfilimine intermediates without using hazardous reagents, so as to fully leverage the potential of enantioselective aza-Mislow-Evans rearrangement.

Alkynyl N-sulfonylhydrazones, known since the 1970s[56], have newly emerged as efficient alkynyl carbenes in various organic transformations[57-60]. Inspired by recent advances in the insertion of alkynyl carbenes into X–H bonds for the synthesis of allene compounds[61-64], we envisioned that S-allenylation of sulfenamides with alkynyl carbenes generated in situ from alkynyl N-sulfonylhydrazones, followed by hydrosulfonylation[65,66], would afford key allylic sulfilimine intermediates. These intermediates could then enable enantioselective aza-Mislow-Evans rearrangement to yield allylic sulfenamides. However, achieving this transformation requires addressing several key challenges: (1) regulating chemoselectivity between the nucleophilic N and S sites in sulfenamides, (2) ensuring highly regioselective attack by the sulfonyl group, and (3) controlling the chirality of allyl group formed during hydrosulfonylation[67], which arises prior to the sigmatropic rearrangement. Herein, we report a novel method for the highly enantioselective aza-Mislow-Evans rearrangement of allylic sulfilimines via chiral dirhodium-catalyzed cascade reaction between sulfenamides and alkynyl carbenes generated in situ from alkynyl triftosylhydrazones under mild conditions (Figure 1C)[68]. This cascade transformation provides a straightforward and practical approach to access chiral allylic sulfenamides, which are valuable synthetic targets in chemical synthesis.

2. Materials and Methods

General Procedure for the Asymmetric Catalysis: Under a nitrogen atmosphere, sulfenamide (0.15 mmol), Rh2(R-p-CF3TPCP)4 (1 mol%), DCE (0.5 mL), and DIPEA (1.0 equiv) were sequentially added to a screw-capped vial (8 mL) with a stir bar. Then the vial was cooled to 0 °C in an ice bath. A solution of alkynyl sulfonylhydrazone (1.25 equiv) in DCE (1 mL) was added dropwise via a syringe, and the mixture was stirred for 15 minutes. Upon completion of the reaction, the residue was purified by silica gel chromatography using petroleum ether/ethyl acetate to afford the desired product. The enantiomeric excess was determined by chiral HPLC analysis. Corresponding racemic samples were prepared under identical conditions using Rh2(OAc)4 as the catalyst.

3. Results

3.1 Initial optimization studies

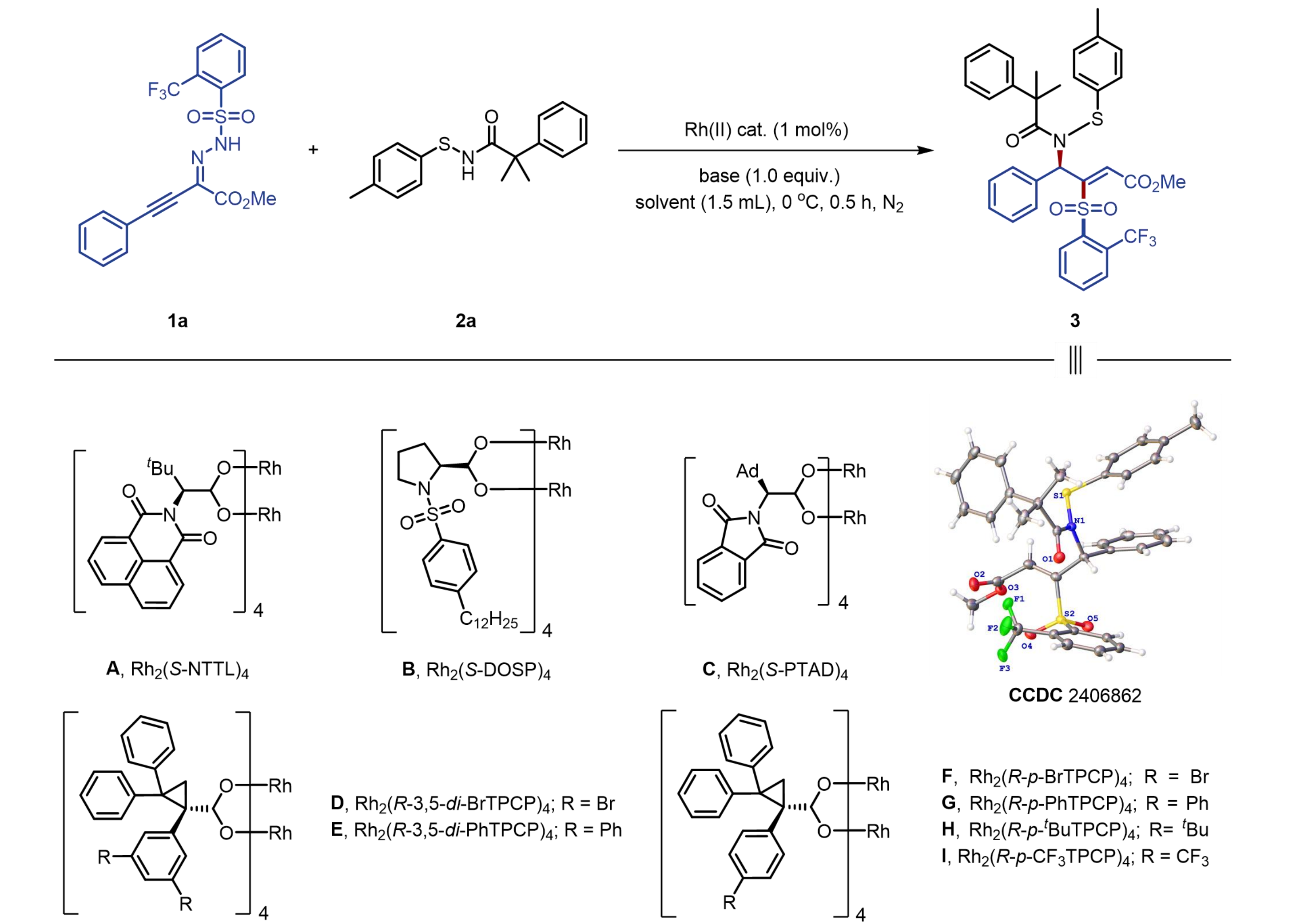

To evaluate the feasibility of our hypothesis, we examined the reaction between readily accessible α-phenylethynyl triftosylhydrazone (1a) and 2-methyl-2-phenyl-N-(p-tolylthio)propanamide (2a), employing various commercially available chiral dimeric Rh(II) tetracarboxylate complexes as catalysts in the presence of 4-cyclohexylmorpholine in dichloroethane (DCE) at 0 °C (Table 1). Initial experiments indicated that the chiral naphthaloyl-based dirhodium catalyst, Rh2(S-NTTL)4, provided the desired N-allylic sulfenamide 3 in low yield and enantioselectivity (Table 1, entry 1). Screening of multiple chiral dirhodium catalysts revealed that sterically hindered dirhodium catalysts substituted with triarylcyclopropanecarboxylate afforded higher enantioselectivities (entries 4-9), among which Rh2(R-p-CF3TPCP)4 provided the highest yield (80%) and enantioselectivity (87% ee, entry 9). However, chiral dirhodium catalysts with N-sulfonylprolinate ligand, Rh2(S-DOSP)4 or phthalimide ligand, Rh2(S-PTAD)4, resulted in lower yields and enantioselectivities. Substituting the base 4-cyclohexylmorpholine with DIPEA further enhanced both the efficiency and enantioselectivity (entry 10). Using N,N-diethylcyclohexylamine as the base (entry 13) afforded only modest yield and enantioselectivity of desired product 3, whereas an inorganic base (e.g., NaH) inhibited the reaction (entry 14). Reducing the amount of DIPEA from 1.0 equiv to 0.1 equiv yielded the desired product 3 in less than 10% yield with 77% enantiomeric excess (entry 11). The replacement of dichloroethane with dichloromethane as the solvent slightly decreased both the yield and enantioselectivity (entry 12). The proposed structure and (R,Z)-configuration (CCDC 2406862) were confirmed by single-crystal X-ray crystallography analysis of product 3.

| Entry | Catalyst | Base | Yield [%]b | Ee [%] |

| 1 | A | 4-cyclohexylmorpholine | 45 | 29 |

| 2 | B | 4-cyclohexylmorpholine | 36 | 17 |

| 3 | C | 4-cyclohexylmorpholine | 41 | 11 |

| 4 | D | 4-cyclohexylmorpholine | 56 | 52 |

| 5 | E | 4-cyclohexylmorpholine | 49 | 59 |

| 6 | F | 4-cyclohexylmorpholine | 82 | 86 |

| 7 | G | 4-cyclohexylmorpholine | 66 | 77 |

| 8 | H | 4-cyclohexylmorpholine | 81 | 85 |

| 9 | I | 4-cyclohexylmorpholine | 80 | 87 |

| 10 | I | DIPEA | 85 | 93 |

| 11c | I | DIPEA | 9 | 77 |

| 12d | I | DIPEA | 80 | 90 |

| 13 | I | CyNEt2 | 61 | 85 |

| 14 | I | NaH | < 3 | n.d. |

a:Reaction Conditions: 2a (0.15 mmol), 1a (1.25 equiv), DIPEA (1 equiv), and chiral dimeric rhodium catalyst (1 mol%) in DCE (1.5 mL) at 0 °C for 0.5 h, N2 atmosphere; b: Isolated yield; c: DIPEA (0.1 equiv); d: DCM; DIPEA: N, N-diisopropylethylamine; DCE: 1,2-dichloroethane; DCM: dichloromethane.

3.2 The reaction scope

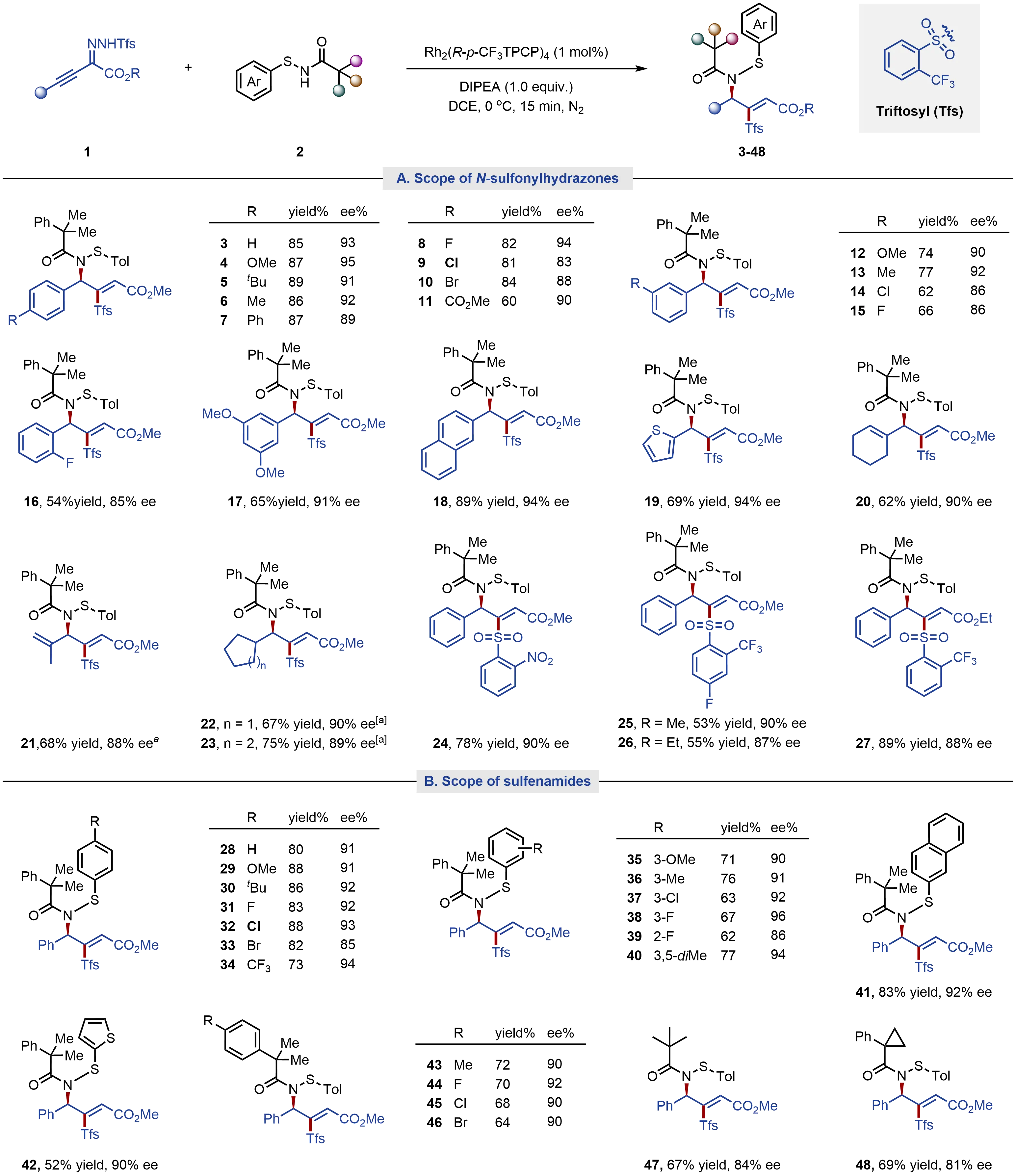

With the optimized reaction conditions in hand, we proceeded to explore the scope of this transformation, initially focusing on various alkynyl triftosylhydrazone inputs 1 while using 2-methyl-2-phenyl-N-(p-tolylthio)propanamide (2a) as the constant coupling partner. As shown in Figure 2A, α-arylalkynyl triftosylhydrazones with electron-donating groups (such as methoxy, tert-butyl, and methyl) or halogen substituents at para-positions of the benzene ring afforded the desired allylic sulfenamides (4-10) in 60-89% yields and 83-95% ee. By contrast, an electron-withdrawing ester functionality slightly lowered the efficiency (11, 60% yield). Under standard conditions, meta- and ortho-substituted and disubstituted α-phenylalkynyl triftosylhydrazones also underwent coupling with high enantioselectivities, albeit with slightly decreased yields (12-17). Notably, halogen functionality retained in the obtained products could provide a versatile synthetic handle for further transformations.

Figure 2. Substrate scope of alkynyl N-sulfonylhydrazones and sulfenamides. Reaction Conditions: alkynyl N-sulfonylhydrazones (0.15 mmol), sulfenamides (1.25 equiv.), DIPEA (1.0 equiv.), and Rh2(R-p-CF3TPCP)4 (1 mol%) in DCE (1.5 mL) at 0 °C for 15 min under N2 atmosphere. Isolated yield. [a]: Rh2(R-p-PhTPCP)4 was used as the catalyst; DIPEA: N, N-diisopropylethylamine; DCE: 1,2-dichloroethane.

2-Naphthyl- and 2-thienyl ring substituted alkynyl triftosylhydrazones were also compatible with the transformation, producing the desired products 18 and 19 in high yields and enantioselectivities. Moreover, alkenyl and cycloalkyl groups at the terminus of alkynyl triftosylhydrazones were also well tolerated (20-23). The influence of substitution on the arenesulfonyl motif of alkynyl N-sulfonylhydrazones were further investigated (24-27). Notably, replacing the ortho-trifluoromethyl group with an ortho-nitro group maintained comparable efficiency (24, 90% ee), while 2-trifluoromethyl-4-fluoro-substituted N-sulfonylhydrazone gave a lower yield (25). The α-ester group in the alkynyl N-sulfonylhydrazone was essential for preserving the reactivity of carbene reagent, with the methyl ester providing higher enantioselectivity than the ethyl ester (3 vs. 27 and 25 vs. 26).

We next explored the scope of various sulfenamide inputs using phenylalkynyl triftosylhydrazone as the carbene precursor (Figure 2B). Various electronically and sterically differentiated S-aryl sulfenamides were well tolerated, furnishing desired (R,Z)-configured allylic sulfenamides (28-40) with good to excellent yields and enantioselectivities. Notably, meta- and ortho-substituted S-phenyl sulfenamides delivered products 35-39 in slightly lower yields than para-substituted substrates. Under the standard reaction conditions, 2-naphthyl sulfenamide coupled effectively with high enantioselectivities (41), while 2-thienyl sulfenamide reacted to afford product 42 in 52% yield and 90% ee. Variations of the N-acyl substituent in sulfenamides suggested that the tertiary alkyl group, composed of an aryl and two alkyl groups, is essential for achieving high enantioselectivity (43-46). In contrast, the N-pivaloyl- or N-phenylcyclopropyl group substituted sulfenamide provided 47 and 48 with slightly lower enantioselectivities. These observations may indicate that favorable π-π interactions between the aryl group in the N-acyl unit and another arene ring in the catalyst/substrate (vide infra). The reactions proceed rapidly, typically reaching near-complete conversion within 15 minutes.

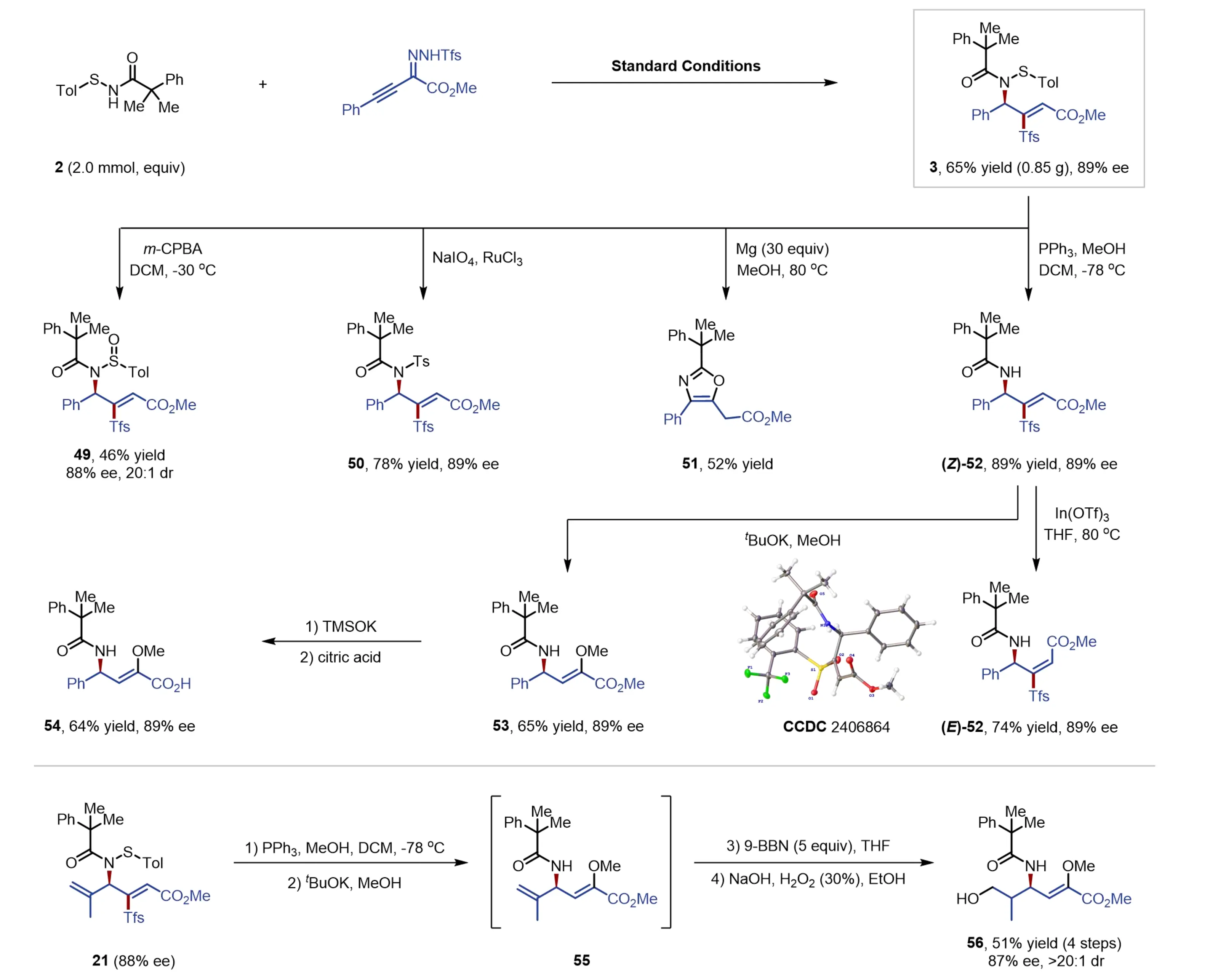

3.3 Synthetic applications

To demonstrate the synthetic utility of the developed methodology, a gram-scale synthesis of product 3 was performed (Figure 3). The comparable outcome (0.85 g, 65% yield, 89% ee) was achieved, highlighting the potential for practical large-scale application. Subsequent transformations were conducted to illustrate the versatility of the newly synthesized allylic sulfenamides (Figure 3, top). Oxidation of 3 with m-CPBA produced the allylic sulfinamide 49 with high diastereoselectivity (20:1 dr), whereas the NaIO4/RuCl3 catalytic system enabled the full oxidation to deliver the desired sulfonamide 50 in good yield without compromising stereoselectivity. Treatment of 3 with magnesium in methanol triggered a desulfonylative cyclization, leading to the formation of oxazoline 51 in 52% yield. Desulfurization of 3 by PPh3 gave allylic amide (Z)-52 in 89% yield with 89% ee, which then readily isomerized into more stable (E)-52 in the presence of In(OTf)3 without losing chirality. The structure of the latter isomer was confirmed by single-crystal X-ray crystallographic analysis (CCDC 2406864). Furthermore, the direct treatment of (Z)-52 with tBuOK in methanol produced methoxy-substituted allylic amide (53) with preserved enantioselectivity via an addition-elimination pathway. Hydrolysis of the ester group of 53 delivered the corresponding chiral carboxylic acid (54) with high enantioselectivity. Additionally, compound 21 was efficiently converted into the primary alcohol 56 through a sequence involving desulfurization, nucleophilic addition and olefin hydration, achieving high enantio- and diastereoselectivity control (Figure 3, bottom). In all cases, the enantiopurity of the chiral products was essentially observed.

Figure 3. Gram-scale synthesis and product derivatizations. DCM: dichloromethane; MeOH: methanol; THF: tetrahydrofuran; EtOH: ethanol; TMSOK: potassium trimethylsilanolate; m-CPBA: meta-chloroperoxybenzoic acid.

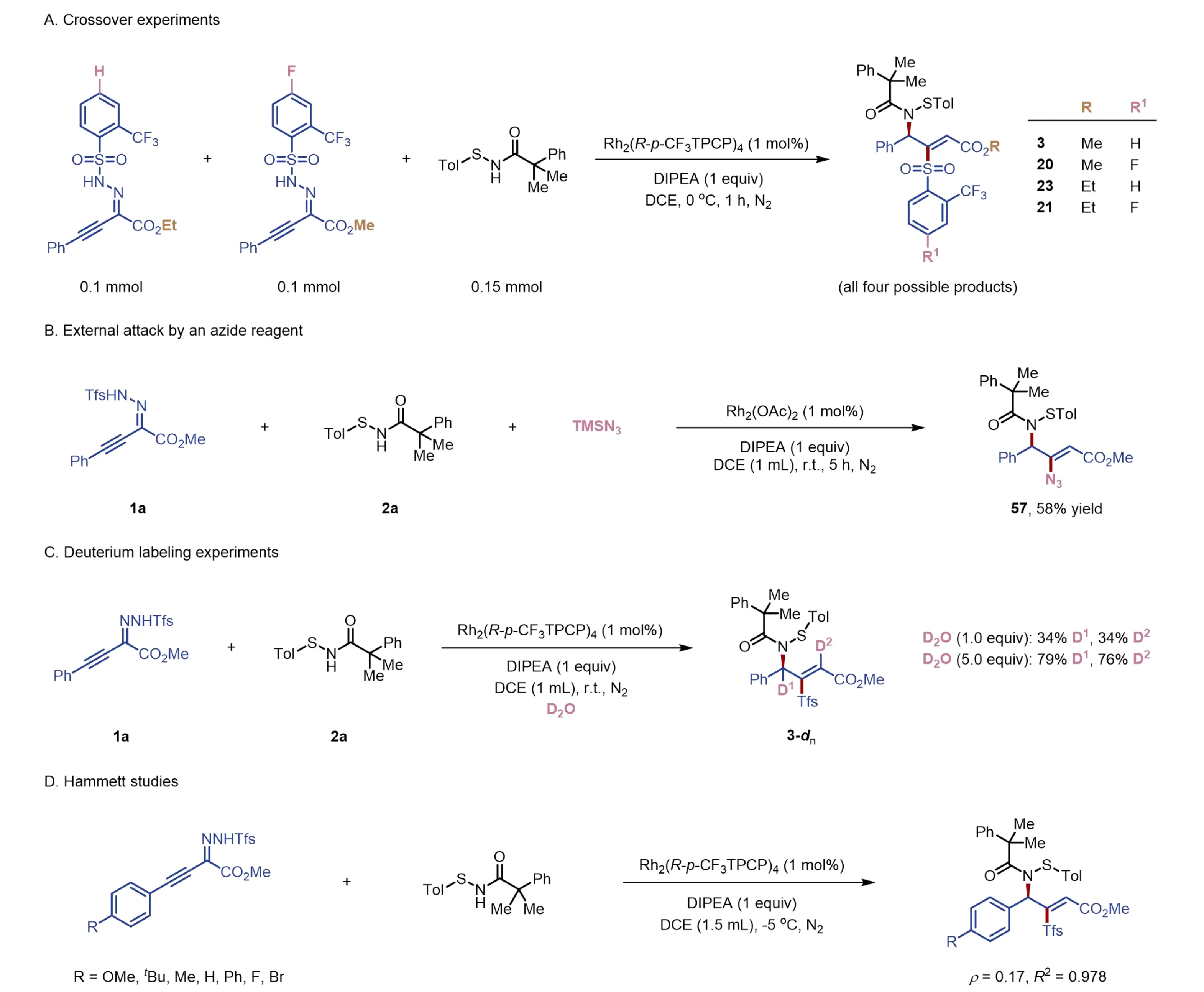

3.4 Experimental mechanistic studies

To shed light on the mechanism of this transformation, a series of experiments were conducted (Figure 4). To probe the crucial role of the sulfenamide moiety, various other NH nucleophiles, such as N-phenyl trifluoroacetamide, pivalamide, N-methoxyamide, or N-tosylamide, were tested as coupling reagents under standard reaction conditions. However, no desired product was observed in any of these cases (see Supplementary Materials). These results suggest that direct N–H insertion of amides is not facile, thereby highlighting the involvement of the sulfur atom in sulfenamide, potentially through the formation of a sulfur ylide or sulfilimine intermediate. A crossover experiment was also conducted using sulfenamide and two alkynyl sulfonylhydrozones differing in both the sulfonyl and ester groups. This reaction afforded all four possible products in comparable yields, as determined by 1H NMR, 19F NMR, and mass spectroscopy, possibly due to substrate crossover interactions (Figure 4A). This result reveals that the sulfonyl group fully dissociates during the reaction and subsequently undergoes intermolecular attack on an electrophilic species. To further support this conclusion, we carried out a control reaction of 1a and 2a in the presence of TMSN3 as an exogenous nucleophile (Figure 4B). Indeed, the alkenyl azide (57) was isolated in decent yield, demonstrating that the azide effectively outcompeted sulfinate as a nucleophile. Afterwards, deuterium labeling experiments were performed with D2O as an additive. Both the allylic and vinylic positions of the product were partially deuterated (Figure 4C). Notably, the degree of deuteration increased with higher amounts of D2O, suggesting that protonation occurs at these two positions in the catalytic cycle (vide infra). Finally, the electronic effect of the sulfonylhydrozone substrate was examined through Hammett studies. By varying the para-substituent on the phenyl ring, a linear correlation was observed with a small positive slope (ρ = 0.17, Figure 4D). This finding suggests that a negative charge may be stabilized in the transition state, potentially during the initial deprotonation-elimination stage or at a later stage of the reaction.

Figure 4. Mechanistic experiments. DIPEA: N, N-diisopropylethylamine; DCE: 1,2-dichloroethane.

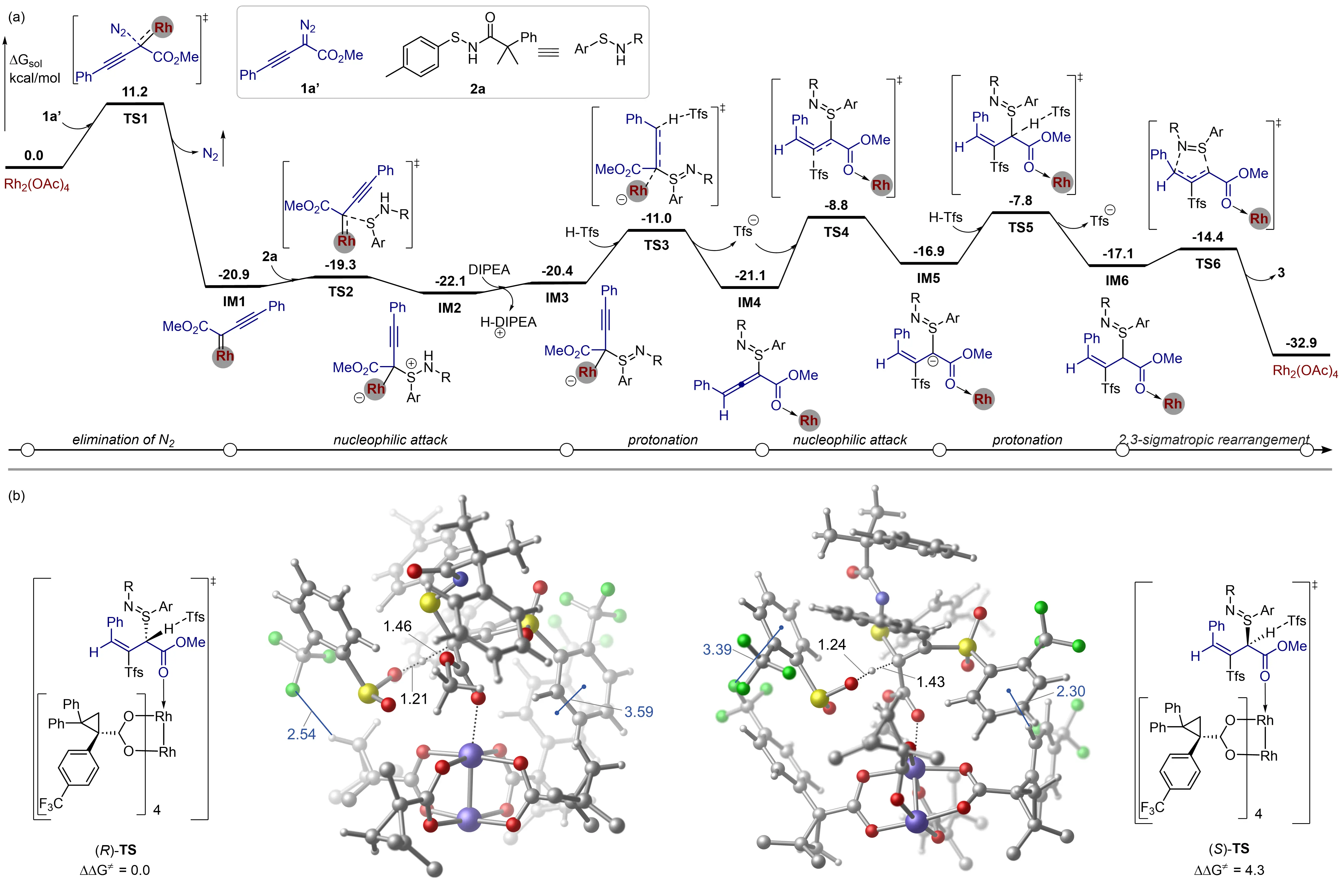

3.5 Computational mechanistic studies

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the detailed reaction mechanism and the origins of the enantioselectivity, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed at the level of B3LYP-D3(BJ)(SMD)/SDD&6-311+G(d,p)//B3LYP-D3(BJ)/SDD&6-31G(d). We selected sulfenamide 2a and the in situ generated diazo species 1a' as model substrates (Figure 5 and the Supplementary Materials). Rh2(OAc)4 was initially employed as the catalyst to establish the reaction mechanism, aiming to reduce computational costs. The calculated energy profile for the most favorable pathway leading to the formation of N-allylic sulfenamide 3 is shown in Figure 5A, with results for alternative pathways presented in the Supplementary Materials. The reaction begins with the elimination of N2 from diazo species 1a' via TS1, with an energy barrier of 11.2 kcal/mol,generating the alkynyl Rh-carbene IM1. Subsequent nucleophilic attack of sulfenamide 2a on the Rh-carbene via TS2 forms the zwitterionic Rh species IM2, which is kinetically accessible, with an energy barrier of only 1.6 kcal/mol relative to IM1. This zwitterionic Rh species IM2 then undergoes deprotonation by DIPEA to yield intermediate IM3. Protonation of IM3 at the alkynyl carbon by TfsH via TS3 delivers a Rh-allene intermediate IM4 along with a Tfs anion. The nucleophilic attack of Tfs anion on the central carbon of the allene occurs via TS4 to generate a stabilized enolate intermediate IM5, which is subsequently protonated via TS5 to afford S-allylic sulfilimine intermediate IM6. Consequently, IM6 undergoes a facile 2,3-sigmatropic aza-Mislow-Evans rearrangement via TS6, yielding the final product 3 and regenerating the Rh2(OAc)4 catalyst. Our calculations reveal that protonation of the enolate in IM5 constitutes the rate-determining step of the overall reaction, with an energy barrier of 14.3 kcal/mol relative to IM2.

Figure 5. DFT calculations. (A) Calculated energy profile of the most favorable pathway with Rh2(OAc)4; (B) Transition states for the protonation of the enolate intermediate with the Rh2(R-p-CF3TPCP)4 catalyst. The spectator aryl groups in the Rh2(R-p-CF3TPCP)4 were omitted for the sake of clarity. Bond distances and energies are given in Å and kcal/mol, respectively. DIPEA: N, N-diisopropylethylamine.

To further elucidate the origins of the enantioselectivity, the protonation of the enolate intermediate by the Rh2(R-p-CF3TPCP)4 catalyst was examined (Figure 5B). Computational analysis suggests that the transition state (R)-TS is lower in energy than that of the (S)-TS by 4.3 kcal/mol, supporting the R enantiomer as the favored product. Given the large size of the system, identifying the precise factors that govern the enantioselectivity remains complex and challenging. However, the optimized geometries reveal the presence of non-covalent interactions (e.g., π---π, F---π, F---H, and C-H---π) in both transition states. Specifically, in (R)-TS, a π---π interaction is observed between the phenyl group of the acyl moiety and the S-Tol group, while (S)-TS exhibits only a C–H---π interaction. This difference likely accounts for the higher energy of (S)-TS compared to (R)-TS, thus facilitating the experimentally observed enantioselectivity.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, we have developed a novel chiral dirhodium-catalyzed cascade reaction between sulfenamides and alkynyl triftosylhydrazones, enabling the enantioselective aza-Mislow-Evans rearrangement of transiently generated allylic sulfilimines to furnish enantioenriched allylic sulfenamides with excellent chemoselectivity, E/Z-selectivity, and enantioselectivity. This transformation operates under mild conditions and accommodates broad substrate scope along with high functional group tolerance. The successful gram-scale reaction and subsequent downstream transformations of enantioenriched allylic sulfinamide products further highlight the synthetic utility of this robust protocol. DFT calculations indicate that the proton transfer step in the stepwise hydrosulfonylation determines the enantioselectivity.

Supplementary materials

The supplementary material for this article is available at: Supplementary materials.

Authors contribution

Li X, Bi X: Conceptualization, writing-original draft.

Wei B: Methodology, investigation.

Wang J: Methodology.

Genping H, Shi Y: Formal analysis.

Xiao J, Mi R, Zhang W: Writing-original draft.

Conflicts of interest

Xingwei Li is the Editor-in-Chief of Chiral Chemistry. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data and materials availability

All data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The data and materials could be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 22371175, 22073066, 22471191, and 22331004).

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

References

-

1. Liu Y, Liu X, Feng X. Recent advances in metal-catalysed asymmetric sigmatropic rearrangements. Chem Sci. 2022;13(42):12290-12308.[DOI]

-

2. Jana S, Guo Y, Koenigs RM. Recent perspectives on rearrangement reactions of ylides via carbene transfer reactions. Chem Eur J. 2021;27(4):1270-1281.[DOI]

-

3. West TH, Spoehrle SSM, Kasten K, Taylor JE, Smith AD. Catalytic stereoselective [2,3]-rearrangement reactions. ACS Catal. 2015;5(12):7446-7479.[DOI]

-

4. Jones AC, May JA, Sarpong R, Stoltz BM. Toward a symphony of reactivity: Cascades involving catalysis and sigmatropic rearrangements. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53(10):2556-2591.[DOI]

-

5. Tejedor D, Méndez-Abt G, Cotos L, García-Tellado F. Propargyl claisen rearrangement: Allene synthesis and beyond. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42(2):458-471.[DOI]

-

6. Ilardi EA, Stivala CE, Zakarian A. [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangements: Recent applications in the total synthesis of natural products. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38(11):3133-3148.[DOI]

-

7. Zhu GY, Zhou JJ, Liu LG, Li X, Zhu XQ, Lu X, et al. Catalyst-dependent stereospecific [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement of sulfoxide-ynamides: Divergent synthesis of chiral medium-sized N,S-heterocycles. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2022;61(28):e202204603.[DOI]

-

8. Kaiser D, Klose I, Oost R, Neuhaus J, Maulide N. Bond-forming and -breaking reactions at sulfur(IV): Sulfoxides, sulfonium salts, sulfur ylides, and sulfinate salts. Chem Rev. 2019;119(14):8701-8780.[DOI]

-

9. Cao Y, Abdolmohammadi S, Ahmadi R, Issakhov A, Ebadi AG, Vessally E. Direct synthesis of sulfenamides, sulfinamides, and sulfonamides from thiols and amines. RSC Adv. 2021;11(51):32394-32407.[DOI]

-

10. Amanpour T, Wang R. Sulfenamide formation–chemical and biochemical reactions and their applications in cell biology. J Sulfur Chem. 2024;45(2):293-312.[DOI]

-

11. Petkowski JJ, Bains W, Seager S. Natural products containing a nitrogen–sulfur bond. J Nat Prod. 2018;81(2):423-446.[DOI]

-

12. Reggelin M. [2,3]-sigmatropic rearrangements of allylic sulfur compounds. In: Schaumann E, editor. Sulfur-mediated rearrangements II. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin, Heidelberg; 2007. p. 1-65.[DOI]

-

13. Rayner DR, Miller EG, Bickart P, Gordon AJ, Mislow K. Mechanisms of thermal racemization of sulfoxides1. J Am Chem Soc. 1966;88(13):3138-3139.[DOI]

-

14. Miller EG, Rayner DR, Mislow K. Thermal rearrangement of sulfenates to sulfoxides1. J Am Chem Soc. 1966;88(13):3139-3140.[DOI]

-

15. Bickart P, Carson FW, Jacobus J, Miller EG, Mislow K. Thermal racemization of allylic sulfoxides and interconversion of allylic sulfoxides and sulfenates. Mechanism and stereochemistry. J Am Chem Soc. 1968;90(18):4869-4876.[DOI]

-

16. Tang R, Mislow K. Rates and equilibria in the interconversion of allylic sulfoxides and sulfenates. J Am Chem Soc. 1970;92(7):2100-2104.[DOI]

-

17. Evans DA, Andrews GC. Allylic sulfoxides. Useful intermediates in organic synthesis. Acc Chem Res. 1974;7(5):147-155.[DOI]

-

18. Miller JG, Kurz W, Untch KG, Stork G. Prostaglandins. 40. J Am Chem Soc. 1974;96(21):6774-6775.[DOI]

-

19. Halcomb RL, Boyer SH, Wittman MD, Olson SH, Denhart DJ, Liu KKC, et al. Studies related to the carbohydrate sectors of esperamicin and calicheamicin: Definition of the stability limits of the esperamicin domain and fashioning of a glycosyl donor from the calicheamicin domain. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117(21):5720-5749.[DOI]

-

20. He C, Zhu C, Dai Z, Tseng CC, Ding H. Divergent total synthesis of indoxamycins A, C, and F. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52(50):13256-13260.[DOI]

-

21. Colomer I, Velado M, Fernández de la Pradilla R, Viso A. From allylic sulfoxides to allylic sulfenates: Fifty years of a never-ending [2,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement. Chem Rev. 2017;117(24):14201-14243.[DOI]

-

22. Ash ASF, Challenger F, Stevens TS, Dunn JL. 527. The isomerisation of sulphilimines. J Chem Soc (Resumed). 1952.[DOI]

-

23. Dolle RE, Osifo KI, Li CS. Enantioselective synthesis of (+)-pinidine. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32(38):5029-5030.[DOI]

-

24. Dolle RE, Li CS, Novelli R, Kruse LI, Eggleston D. Enantiospecific synthesis of (-)-tabtoxinine .beta.-lactam. J Org Chem. 1992;57(1):128-132.[DOI]

-

25. Armstrong A, Challinor L, Moir JH. Exploiting organocatalysis: Enantioselective synthesis of vinyl glycines by allylic sulfimide [2,3] sigmatropic rearrangement. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46(28):5369-5372.[DOI]

-

26. Armstrong A, Challinor L, Cooke RS, Moir JH, Treweeke NR. Oxaziridine-mediated amination of branched allylic sulfides: Stereospecific formation of allylic amine derivatives via [2,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement. J Org Chem. 2006;71(10):4028-4030.[DOI]

-

27. Armstrong A, Emmerson DPG. Enantioselective synthesis of allenamides via sulfimide [2,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement. Org Lett. 2009;11(7):1547-1550.[DOI]

-

28. Armstrong A, Deacon N, Donald C. Enantioselective synthesis of α-aminophosphonates via organocatalytic sulfenylation and [2,3]-sigmatropic sulfimide rearrangement. Synlett. 2011;2011(16):2347-2350.[DOI]

-

29. Kano T, Sakamoto R, Maruoka K. Remote chirality control based on the organocatalytic asymmetric mannich reaction of α-thio acetaldehydes. Chem Commun. 2014;50(8):942-944.[DOI]

-

30. Takada H, Nishibayashi Y, Ohe K, Uemura S. Novel asymmetric catalytic synthesis of sulfimides. Chem Commun. 1996.[DOI]

-

31. Takada H, Nishibayashi Y, Ohe K, Uemura S, Baird CP, Sparey TJ, et al. Catalytic asymmetric sulfimidation. J Org Chem. 1997;62(19):6512-6518.[DOI]

-

32. Murakami M, Katsuki T. Chiral (OC)Ru(salen)-catalyzed tandem sulfimidation and [2,3]sigmatropic rearrangement: Asymmetric C N bond formation. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43(21):3947-3949.[DOI]

-

33. Murakami M, Uchida T, Saito B, Katsuki T. Ru(salen)-catalyzed asymmetric sulfimidation and subsequent [2,3]sigmatropic rearrangement. Chirality. 2003;15(2):116-123.[DOI]

-

34. Prier CK, Hyster TK, Farwell CC, Huang A, Arnold FH. Asymmetric enzymatic synthesis of allylic amines: A sigmatropic rearrangement strategy. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55(15):4711-4715.[DOI]

-

35. Ma LJ, Chen SS, Li GX, Zhu J, Wang QW, Tang Z. Chiral Brønsted-acid-catalyzed asymmetric oxidation of sulfenamide by using H2O2: A versatile access to sulfinamide and sulfoxide with high enantioselectivity. ACS Catal. 2019;9(2):1525-1530.[DOI]

-

36. Ma L, Bai L, Yu Z, Shen Q. Chiral Brønsted acid catalyzed asymmetric oxidation of N-acyl sulfenamide by H2O2: An efficient approach to obtaining chiral N-acyl sulfinamide. Chirality. 2022;34(9):1191-1196.[DOI]

-

37. Yang GF, Yuan Y, Tian Y, Zhang SQ, Cui X, Xia B, et al. Synthesis of chiral sulfonimidoyl chloride via desymmetrizing enantioselective hydrolysis. J Am Chem Soc. 2023;145(9):5439-5446.[DOI]

-

38. Champlin AT, Kwon NY, Ellman JA. Enantioselective S-alkylation of sulfenamides by phase-transfer catalysis. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2024;63(42):e202408820.[DOI]

-

39. Fang W, Meng YD, Ding SY, Wang JY, Pei ZH, Shen ML, et al. Asymmetric S-arylation of sulfenamides to access axially chiral sulfilimines enabled by anionic stereogenic-at-cobalt(III) complexes. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2025;64(7):e202419596.[DOI]

-

40. Fimm M, Saito F. Enantioselective synthesis of sulfinamidines via asymmetric nitrogen transfer from N−H oxaziridines to sulfenamides. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2024;63(35):e202408380.[DOI]

-

41. Liang Q, Zhang X, Rotella ME, Xu Z, Kozlowski MC, Jia T. Enantioselective chan–lam S-arylation of sulfenamides. Nat Catal. 2024;7(9):1010-1020.[DOI]

-

42. Wang F, Xiang W, Xie Y, Huai L, Zhang L, Zhang X. Synthesis of chiral sulfilimines by organocatalytic enantioselective sulfur alkylation of sulfenamides. Sci Adv. 2024;10(37):eadq2768.[DOI]

-

43. Yuan Y, Han Y, Zhang ZK, Sun S, Wu K, Yang J, et al. Enantioselective arylation of sulfenamides to access sulfilimines enabled by palladium catalysis. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2024;63(37):e202409541.[DOI]

-

44. Boyer ZW, Kwon NY, Ellman JA. Ruthenium-catalyzed enantioselective alkylation of sulfenamides: A general approach for the synthesis of drug relevant S-methyl and S-cyclopropyl sulfoximines. J Am Chem Soc. 2025;147(18):14954-14959.[DOI]

-

45. Cui WL, Zhang L, Liu C, Su J, Zhang HR, Ma R, et al. Reagent-regulated organocatalytic enantiodivergent synthesis of chiral sulfinimidate esters. J Am Chem Soc. 2025;147(23):19986-19995.[DOI]

-

46. Fan LW, Tang JB, Wang LL, Gao Z, Liu JR, Zhang YS, et al. Copper-catalysed asymmetric cross-coupling reactions tolerant of highly reactive radicals. Nat Chem. 2025.[DOI]

-

47. He M, Zhang R, Wang T, Xue XS, Ma D. Assembly of (hetero)aryl sulfilimines via copper-catalyzed enantioselective S-arylation of sulfenamides with (hetero)aryl iodides. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):2310.[DOI]

-

48. Huang HS, Yuan Y, Wang W, Zhang SQ, Nie XK, Yang WT, et al. Enantioselective synthesis of chiral sulfonimidoyl fluorides facilitates stereospecific suFEx click chemistry. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2025;64(4):e202415873.[DOI]

-

49. Jiang HJ, Fang W, Chen X, Yu XR, Meng YD, Fang LP, et al. Unlocking chiral sulfinimidoyl electrophiles: Asymmetric synthesis of sulfinamides catalyzed by anionic stereogenic-at-cobalt(III) complexes. J Am Chem Soc. 2025;147(2):2137-2147.[DOI]

-

50. Li HP, Zhao Z, Zhang X, He XH, Peng C, Zhan G, et al. Unlocking catalytic asymmetric transformations of sulfilimidoyl fluorides: Approach to chiral sulfinimidate esters. ChemRxiv [Perprint]. 2025.[DOI]

-

51. Tampellini N, Choi ES, Miller SJ. Peptide-catalyzed asymmetric amination of sulfenamides enabled by DFT-guided catalyst optimization. J Am Chem Soc. 2025;147(44):41122-41129.[DOI]

-

52. Wang Y, Mu Y, Han X, Xiao J, Huang G, Wang F, et al. Copper-catalyzed asymmetric C–H sulfilimination of arenes via HAT-primed C–S radical–radical coupling. J Am Chem Soc. 2025;147(42):38931-38941.[DOI]

-

53. Wu XB, Shen Y, Jiang HJ, Gong LZ. Cu-catalyzed enantioselective S-arylation of sulfenamides enabled by confined ligands. Org Lett. 2025;27(12):2845-2851.[DOI]

-

54. Zhang R, Wang T, He M, Xue XS, Ma D. Enantioselective assembly of (hetero)aryl alkyl sulfilimines via copper-catalyzed S-arylation of S-alkyl sulfenamides with (hetero)aryl iodides. J Am Chem Soc. 2025;147(37):34126-34131.[DOI]

-

55. Xiao Z, Pu M, Li Y, Yang W, Wang F, Feng X, et al. Asymmetric catalytic synthesis of allylic sulfenamides from vinyl α-diazo compounds by a rearrangement route. Angewe Chem Int Ed. 2025;64(2):e202414712.[DOI]

-

56. Kabalka GW, Newton RJ, Chandler JH, Yang DT. Synthesis of allenes via reduction of acetylenic tosylhydrazones. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1978.[DOI]

-

57. Liu Z, Zhang X, Zanoni G, Bi X. Silver-catalyzed cyclopropanation of alkenes using N-nosylhydrazones as diazo surrogates. Org Lett. 2017;19(24):6646-6649.[DOI]

-

58. Ke J, Lee WCC, Wang X, Wang Y, Wen X, Zhang XP. Metalloradical activation of in situ-generated α-alkynyldiazomethanes for asymmetric radical cyclopropanation of alkenes. J Am Chem Soc. 2022;144(5):2368-2378.[DOI]

-

59. Ning Y, Huo M, Wu L, Bi X. Silver-catalyzed cyclopropanation of alkenes with alkynyl N-nosylhydrazones leading to alkynyl cyclopropanes. Chem Commun. 2022;58(21):3485-3488.[DOI]

-

60. Huo M, Ning Y, Zheng X, Han X, Karmakar S, Sun J, et al. Synthesis of propargyl boranes via silver catalyzed insertion of alkynyl carbene into B-H bond. ChemCatChem. 2023;15(2):e202201381.[DOI]

-

61. Yang Y, Liu Z, Porta A, Zanoni G, Bi X. Alkynyl N-nosylhydrazones: Easy decomposition to alknynl diazomethanes and application in allene synthesis. Chem Eur J. 2017;23(38):9009-9013.[DOI]

-

62. Yang LL, Ouyang J, Zou HN, Zhu SF, Zhou QL. Enantioselective insertion of alkynyl carbenes into Si–H bonds: An efficient access to chiral propargylsilanes and allenylsilanes. J Am Chem Soc. 2021;143(17):6401-6406.[DOI]

-

63. Ning Y, Song Q, Sivaguru P, Wu L, Anderson EA, Bi X. Ag-catalyzed insertion of alkynyl carbenes into C–C bonds of β-ketocarbonyls: A formal C(sp2) insertion. Org Lett. 2022;24(2):631-636.[DOI]

-

64. Zou HN, Zhao YT, Yang LL, Huang MY, Zhang JW, Huang ML, et al. Catalytic asymmetric synthesis of chiral propargylic boron compounds through B–H bond insertion reactions. ACS Catal. 2022;12(17):10654-10660.[DOI]

-

65. Patel S, Greenwood NS, Mercado BQ, Ellman JA. Rh(II)-catalyzed enantioselective S-alkylation of sulfenamides with acceptor–acceptor diazo compounds enables the synthesis of sulfoximines displaying diverse functionality. Org Lett. 2024;26(29):6295-6300.[DOI]

-

66. Greenwood NS, Champlin AT, Ellman JA. Catalytic enantioselective sulfur alkylation of sulfenamides for the asymmetric synthesis of sulfoximines. J Am Chem Soc. 2022;144(39):17808-17814.[DOI]

-

67. Jia S, Chen Z, Zhang N, Tan Y, Liu Y, Deng J, et al. Organocatalytic enantioselective construction of axially chiral sulfone-containing styrenes. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140(23):7056-7060.[DOI]

-

68. Sivaguru P, Pan Y, Wang N, Bi X. Who is who in the carbene chemistry of N-sulfonyl hydrazones. Chin J Chem. 2024;42(17):2071-2108.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite