Lihan Zhu, Key Laboratory of Functional Organic Molecule Design & Synthesis of Jilin Province, Department of Chemistry, Northeast Normal University, Changchun 130024, Jilin, China. E-mail: zhulh168@nenu.edu.cn

Xinhu Hu, School of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Shenyang University of Chemical Technology, Shenyang 110142, Liaoning, China. E-mail: jlhuxinhu@163.com

Guangfan Zheng, Key Laboratory of Functional Organic Molecule Design & Synthesis of Jilin Province, Department of Chemistry, Northeast Normal University, Changchun 130024, Jilin, China. E-mail: zhenggf265@nenu.edu.cn

Abstract

The synthesis of biaryl axially chiral amides and their derivatives—compounds that have shown promise as additives or catalysts in asymmetric catalysis—has traditionally relied on transition-metal catalysts. Herein, we report an NHC-catalyzed organocatalytic atropoenantioselective amidation between axially prochiral biaryl dialdehydes and amides that efficiently affords axially chiral imides. This method operates under metal-free and mild conditions, exhibits broad functional group tolerance and substrate scope, and delivers products with excellent enantioselectivities. Furthermore, a wide variety of axially chiral imides, amides, and related derivatives can be accessed through enantio-retentive transformations, offering a versatile and attractive strategy for their synthesis.

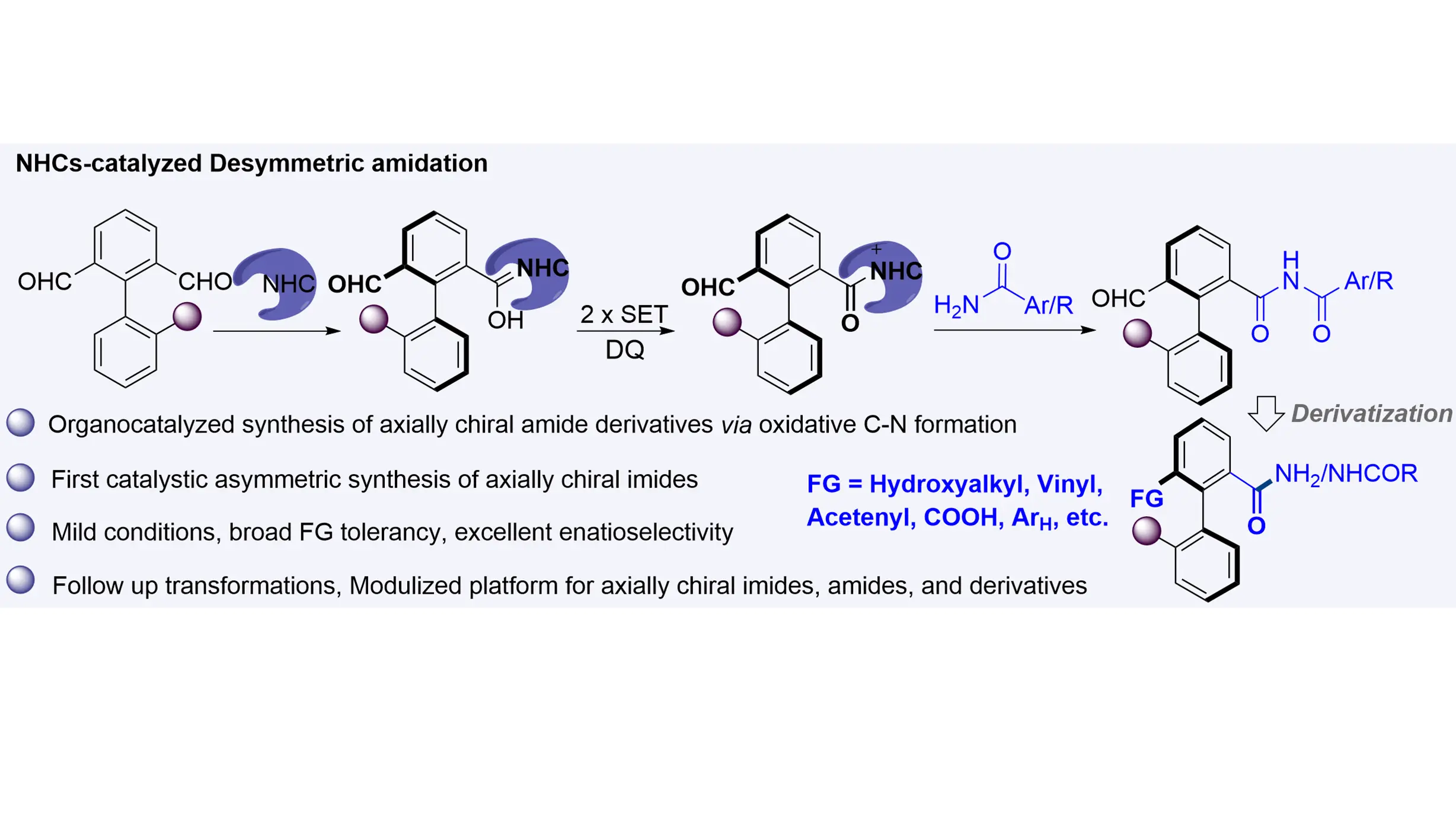

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

1. Introduction

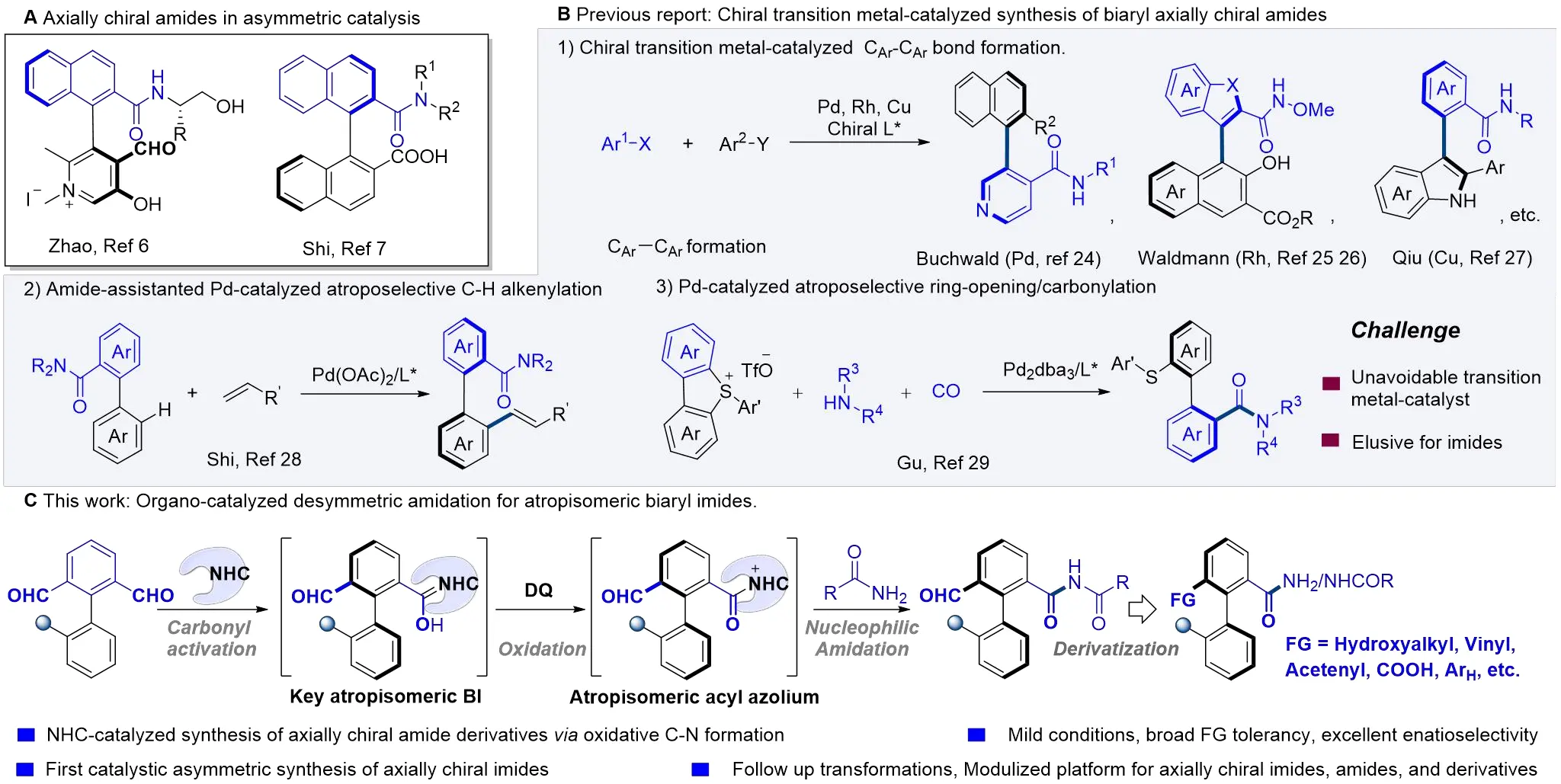

The asymmetric synthesis of biaryl axially chiral frameworks has attracted considerable interest owing to their widespread presence in biologically active molecules[1,2], pharmaceuticals[3,4], and functional materials[5,6], as well as their privileged role as chiral ligands and catalysts[7-11]. Significant advances have been achieved in the construction of such axially chiral architectures[12-17]. In particular, biaryl axially chiral amides and their derivatives have emerged as highly promising additives or catalysts in asymmetric reactions, exemplified by the carbonyl catalysis developed by Zhao et al.[18,19] and their efficient application as chiral additives/ligands in asymmetric C–H functionalization by the Shi group[20-23] (Scheme 1A). Despite the importance of axially chiral amides, catalytic methods for their synthesis remain underdeveloped. To date, only three primary strategies have been reported (Scheme 1B): (1) transition-metal-catalyzed enantioselective arylation of amide-substituted aromatics for constructing a CAr–CAr axis[24-27]; (2) Pd-catalyzed atropoenantioselective C–H functionalization using amides as directing groups[28]; and (3) Pd-catalyzed atroposelective ring-opening/carbonylation of cyclic diarylsulfonium salts[29]. Despite impressive progress, these successful transformations still rely on transition-metal catalysts. Achieving modular and flexible access to highly enantioenriched biaryl axially chiral amides and their derivatives under metal-free conditions remains a challenging issue. Furthermore, existing data indicate a lack of research on the catalytic synthesis of axially chiral biaryl imides.

Scheme 1. Catalytic enantioselective synthesis of biaryl axially chiral amides/imides. DQ: 2,3-Dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone; NHC: N-heterocyclic carbene.

The unique capability of N-Heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs) to activate carbonyl group has made them extensively utilized in organic synthesis and asymmetric catalysis[30-41]. Desymmetrization[42-46], that disrupts symmetry to convert meso or prochiral compounds into enantiomerically enriched products, offers an attractive and efficient strategy for constructing complex chiral molecules. Systematic work by Chi[47-50], Veselý[51], Biju[52], Ye[53], and our group[54,55] has demonstrated the utility of NHC-catalyzed enantioselective desymmetrization of prochiral dialdehydes, enabling access to carbonyl compounds bearing central[47-49], planar[50,51], and axial[52-68] chirality. Mechanistically, NHC catalysis generates chiral Breslow intermediates from dialdehydes, which then undergo functionalization to afford enantioenriched products. We envisioned that NHC-catalyzed desymmetrization of axially prochiral biaryl dialdehydes could provide a viable route to challenging asymmetric amidations[69-77] with high reactivity and selectivity. However, several obstacles must be overcome: (1) precise modulation of nucleophilicity is essential to avoid condensation between the aminating reagent and the aldehydes; and (2) over-functionalization of the dialdehyde substrates must be controlled. As part of our continuous research in NHC catalysis[78-83] and axial chirality [54,55,64,67,84], we herein report the first enantioselective synthesis of axially chiral biaryl imides via NHC-catalyzed desymmetrizative amidation of biaryl dialdehydes with amines (Scheme 1C).

2. Experimental

Representative Synthesis of Product R-3aa (standard conditions A): The reaction was conducted in a flame-dried screw-cap tube equipped with a Teflon-coated magnetic stir bar. Under a nitrogen atmosphere in a glovebox, the tube was charged with C1 (8.36 mg, 20 mol%), Cs2CO3 (49.0 mg, 1.5 equiv), and 1a (29 mg, 0.1 mmol). Anhydrous dichloromethane (1.0 mL) was added, and the mixture was stirred for 5 minutes. Benzamide 2a (36.3 mg, 3.0 equiv) and DQ (48 mg, 1.2 equiv) were then added. The tube was sealed with a septum-equipped PTFE screw cap (Thermo Scientific), removed from the glovebox, and the reaction mixture was stirred at 30 °C for 72 h. After the reaction was complete, as indicated by TLC analysis, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure, and the residue was purified by silica gel chromatography using petroleum ether/ethyl acetate 4:1 (v/v) to give product R-3aa. Further details are provided in the Supporting Information.

3. Results and Discussion

To validate our hypothesis, we initiated the investigation using biaryl dialdehyde 1a as a model axially prochiral substrate and benzamide 2a as the amidation reagent to identify optimal reaction conditions. Key optimization results are summarized in Table 1. In the initial trial, treatment of 1a (0.1 mmol) with 2a (3.0 equiv) and DQ (1.2 equiv) in DCM (1.0 mL), catalyzed by the aminoindanol-derived precatalyst C1 (10 mol%) bearing an N-mesityl group at 0 °C under a N2 atmosphere for 72 h, afforded the desired amidation product 3aa with excellent enantioselectivity, albeit in low yield (Table 1, entry 1). Several solvents, including CHCl3, THF, and MTBE, supported the transformation but were less effective than DCM (entries 2-4). The use of MeCN improved the yield at the cost of reduced enantioselectivity (entry 5). After evaluation, DCM was selected as the optimal solvent for further parameter screening. Alternative organic (DBU) and inorganic bases (K2CO3, K3PO4) proved inferior (entries 6-8). Notably, raising the temperature to 30 °C improved both the yield (50%) and enantioselectivity (99% ee, entry 9). We next examined structural variations of the NHC catalyst. Replacing the N-mesityl group in C1 with the sterically more hindered tri-ethyl-phenyl group (C2) led to a lower yield (34%) with no significant change in enantioselectivity (entry 10). The more electron-deficient pentafluorophenyl-substituted catalyst C3 was ineffective (entry 11). Catalyst C4, featuring a bromo-substituted indanol ring, provided 3aa in 40% yield and 99% ee (entry 12). Aryl-alanine-derived catalysts C5 and C6 did not improve the outcome (entry 13 and 14). Finally, increasing the catalyst loading to 20 mol% markedly enhanced the conversion, delivering 3aa in 75% yield with retained enantioselectivity (99% ee, entry 15). Accordingly, the conditions in entry 15 were established as the standard for subsequent studies.

| Entry | NHC Cat | Solvent | Base | Conv. (%) | 3aa (%) | |

| Yield | ee | |||||

| 1 | C1 | DCM | Cs2CO3 | 40 | 35 | 98 |

| 2 | C1 | CHCl3 | Cs2CO3 | 50 | 30 | 95 |

| 3 | C1 | THF | Cs2CO3 | 50 | 23 | 99 |

| 4 | C1 | MTBE | Cs2CO3 | 30 | 17 | 60 |

| 5 | C1 | MeCN | Cs2CO3 | 69 | 60 | 94 |

| 6 | C1 | DCM | DBU | 65 | 31 | 94 |

| 7 | C1 | DCM | K2CO3 | 30 | 10 | 70 |

| 8 | C1 | DCM | K3PO4 | 29 | Trace | -- |

| 9b | C1 | DCM | Cs2CO3 | 65 | 50 | 99 |

| 10b | C2 | DCM | Cs2CO3 | 60 | 34 | 98 |

| 11b | C3 | DCM | Cs2CO3 | -- | Trace | -- |

| 12b | C4 | DCM | Cs2CO3 | 79 | 40 | 99 |

| 13b | C5 | DCM | Cs2CO3 | 98 | 60 | 87 |

| 14b | C6 | DCM | Cs2CO3 | 50 | 18 | 32 |

| 15b,c | C1 | DCM | Cs2CO3 | 98 | 77(75) | 99 |

a: Unless otherwise noted, all the reactions were carried out with 1a (0.1 mmol), 2a (3.0 equiv), NHCs (10 mol%), base (1.5 equiv) and DQ (1.2 equiv), solvent (1.0 mL), 0 °C, N2 atmosphere, 72 h. Yields were determined by 1H NMR spectroscopic analysis of the crude reaction mixture employing CH2Br2 as the internal standard; isolated yield was provided in parentheses. ee was determined by chiral-phase HPLC analysis; b: 30 °C; c: C1 (20 mol%). DQ: 2,3-Dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone; HPLC: high-performance liquid chromatography; NHCs: N-Heterocyclic carbenes; DCM: dichloromethane; THF: tetrahydrofuran; MTBE: methyl tert-butyl ether; DBU: 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene.

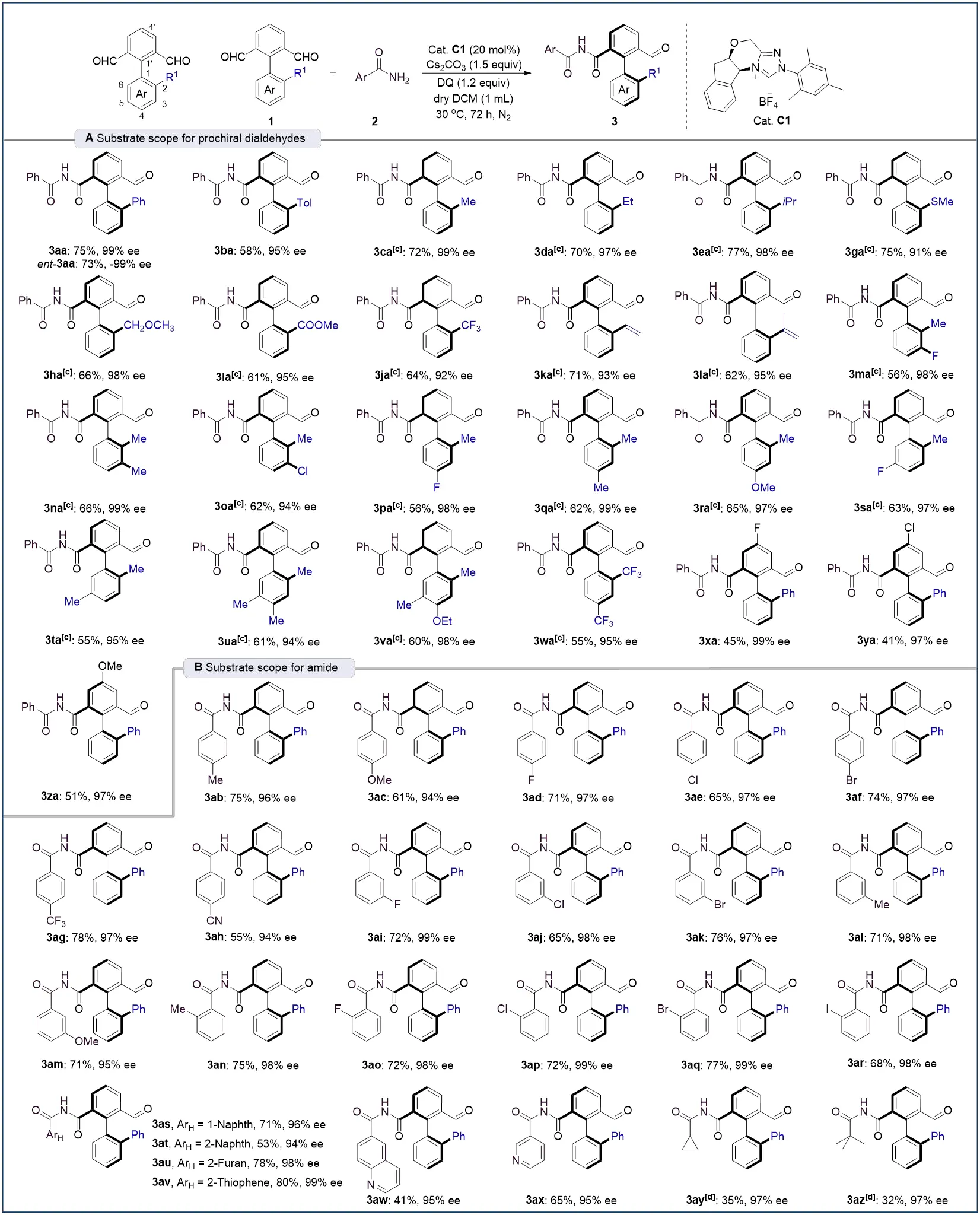

We next evaluated the scope and limitations of the atroposelective oxidative amidation under the standard reaction conditions. The investigation began with axially prochiral biaryl dialdehydes (Scheme 2A). A range of blocking groups at the 2-position including aryl (3aa, 3ab), alkyl (3ca–3ea), thiomethyl (3ga), methoxymethyl (3ha), ester carbonyl (3ia), trifluoromethyl (3ja), and alkenyl (3ka,3la) substituents were well tolerated in the atroposelective aldehyde C–H amidation, affording the corresponding axially chiral imides in yields ranging from 58% to 77% with excellent enantioselectivities (up to 99% ee). Employing ent-C1 as the catalyst afforded ent-3aa in 73% yield with -99% ee. Dialdehydes bearing disubstituted or trisubstituted arenes with a fixed methyl group at the 2-position also proved to be viable substrates, delivering products 3ma-3va in moderate yields (56-66%) and high enantiomeric ratios (94-99% ee). Notably, the presence of a 2,4-bis(trifluoromethyl) substituent on the aryl ring did not significantly impair reactivity or selectivity, as product 3wa was obtained in 51% yield and 97% ee. Further evaluation of 4′-substituted dialdehydes containing a fixed phenyl group at the 2-position afforded the desired axially chiral imides 3xa-3za with excellent enantioselectivities and moderate yields. However, the naphthalene-based dialdehyde 1a’ afforded product 1a'a in only 32% yield with 70% ee.

Scheme 2. Substrate scope for catalytic synthesis of axially chiral imide. a,b aCondition A: Unless otherwise noted, all the reactions were carried out with 1 (0.1 mmol), 2 (0.3 mmol), C1 (20 mol%), DQ (1.2 equiv), Cs2CO3 (1.5 equiv), and dry DCM (1.0 mL) at 30 °C under N2 atmosphere for 72 h; b: Isolated yield, ee was determined by chiral-phase HPLC analysis; c: Reactions were carried out with C1 (10 mol%); d: Reactions were carried out with 2 (5.0 equiv). DQ: 2,3-Dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone; DCM: dichloromethane; HPLC: high-performance liquid chromatography.

The scope of amide coupling partners was also examined (Scheme 2B). Aryl amides featuring electron-donating, halogen, or electron-withdrawing groups at the para-position reacted smoothly to furnish products 3ab-3ah in 55-78% yield and 94-99% ee, demonstrating broad electronic tolerance. Substituents at the meta- or ortho-positions had minimal impact on reaction efficiency and enantiocontrol, as evidenced by the formation of enantioenriched products 3ai-3ar. Notably, the incorporation of halogen atoms, particularly iodine (3ar) and bromine (3af, 3ak, 3aq), offers valuable handles for further functionalization via cross-coupling reactions. The method was also compatible with fused-ring arenes (3as, 3at), electron-rich (3au, 3av), and electron-deficient heteroaromatic amides (3aw, 3ax). Finally, alkyl amides (3ay, 3az) proved applicable, affording products with excellent enantioselectivity, albeit with somewhat reduced reactivity.

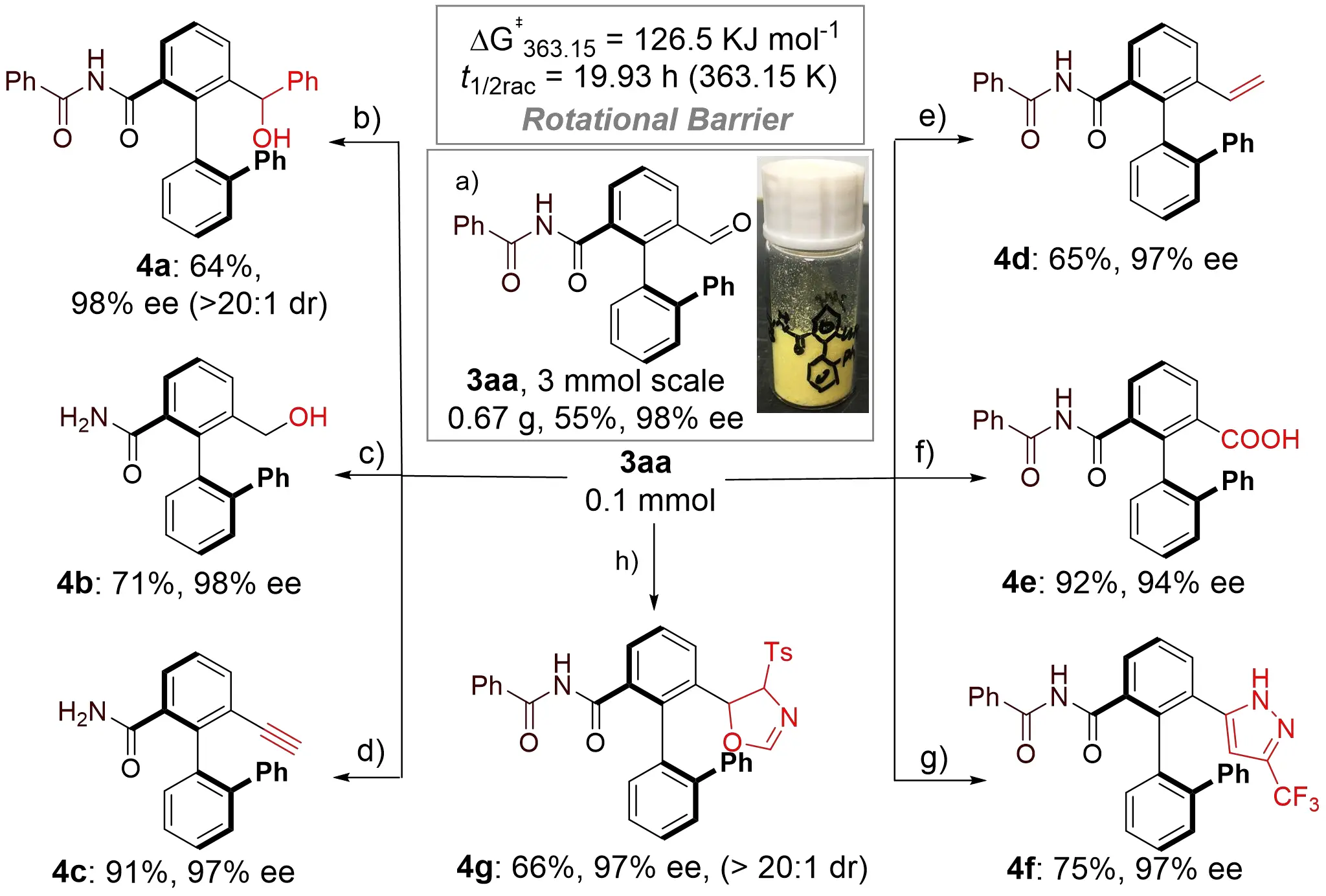

To further demonstrate the synthetic utility of the enantioselective oxidative amidation system, gram-scale synthesis and derivatization were carried out. The reaction was conducted on a 3.0 mmol scale, affording (R)-3aa in 55% yield (0.67 g) with 98% ee (Scheme 3a). This reduction in yield is presumably due to the poor solubility of the amide, creating a heterogeneous mixture. In the larger-scale setup, this inhomogeneity likely caused the amide to precipitate and settle at the bottom of the flask, thereby compromising the reaction efficiency. The formyl and imine groups serve as highly versatile functional handles for further transformations. For instance, diastereoselective nucleophilic addition of PhMgBr to 3aa yielded axially chiral secondary alcohol 4a with 65% yield, 98% ee, and > 20:1 dr (Scheme 3b). Reduction of the formyl group in 3aa with NaBH₄, followed by cascade hydrolysis of the imide, provided axially chiral alcohol 4b in 71% yield and 98% ee (Scheme 3c). Seyferth-Gilbert homologation of 3aa produced alkynyl-containing axially chiral amide 4c in 91% yield and 97% ee (Scheme 3d), while a Wittig reaction delivered alkenyl-substituted axially chiral imide 4d in 65% yield and 97% ee (Scheme 3e). Oxidation of the formyl group afforded valuable axially chiral carboxylic acid 4e in 92% yield, albeit with slightly reduced enantioselectivity (Scheme 3f). Cascade annulation of 3aa with TsNHNH₂ and 2-bromo-3,3,3-trifluoropropene yielded pyrazole 4f (Scheme 3g), and cycloaddition with tosylmethyl isocyanide furnished product 4g in 66% yield and 97% ee with excellent diastereoselectivity (Scheme 3h). The rotational barrier of the C(aryl)–C(aryl) bond in 3aa was determined to be ΔG‡rac = 126.5 kJ/mol, corresponding to a half-life of 19.9 hours at 90 °C in i-PrOH. This high configurational stability ensures significant chiral retention during subsequent transformations, establishing a robust strategy for the synthesis of axially chiral imides, amides, and related derivatives.

Scheme 3. Large-scale synthesis and follow-up transformations. Reaction conditions: (a) C1 (20 mol%), Cs2CO3 (1.5 equiv), DQ (1.2 equiv), dry DCM (0.1 M), 25 °C, N2, 72 h; (b) PhMgBr (1.1 equiv), dry THF (0.1 M), 0 °C, 48 h, 2, H3+O; (c) NaBH4 (1.0 equiv), THF/CH3OH = 3:1 (0.1 M), 0 °C, 12 h; (d) P-(1-diazo-2-oxopropyl)-diMethylester (1.5 equiv), K2CO3 (2.0 equiv), MeOH (1 mL), rt. 3 h; (e) (PPh)3P--CH3Br+ (1.2 equiv), nBuLi (1.2 equiv), dry THF (0.1 M), 0 °C, 30 min, then drop 3aa, rt, 12 h; (f) NaClO2 (3.7 equiv), NaH2PO4 (5.0 equiv), 2-methylbut-2-ene (13.0 equiv), tBuOH (0.15 M), rt, overnight; (g) TsNHNH2 (1.2 equiv), 2-Bromo-3,3,3-trifluoropropene (2.0 equiv), DBU (3.0 equiv), PhMe (1 mL), 60 °C, 6 h; (h) Tosylmethyl isocyanide (1.0 equiv), Cs2CO3 (2.0 equiv), DMF (0.05 M), 25 °C, N2, 8 h. DCM: dichloromethane; THF: tetrahydrofuran; DBU: 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene.

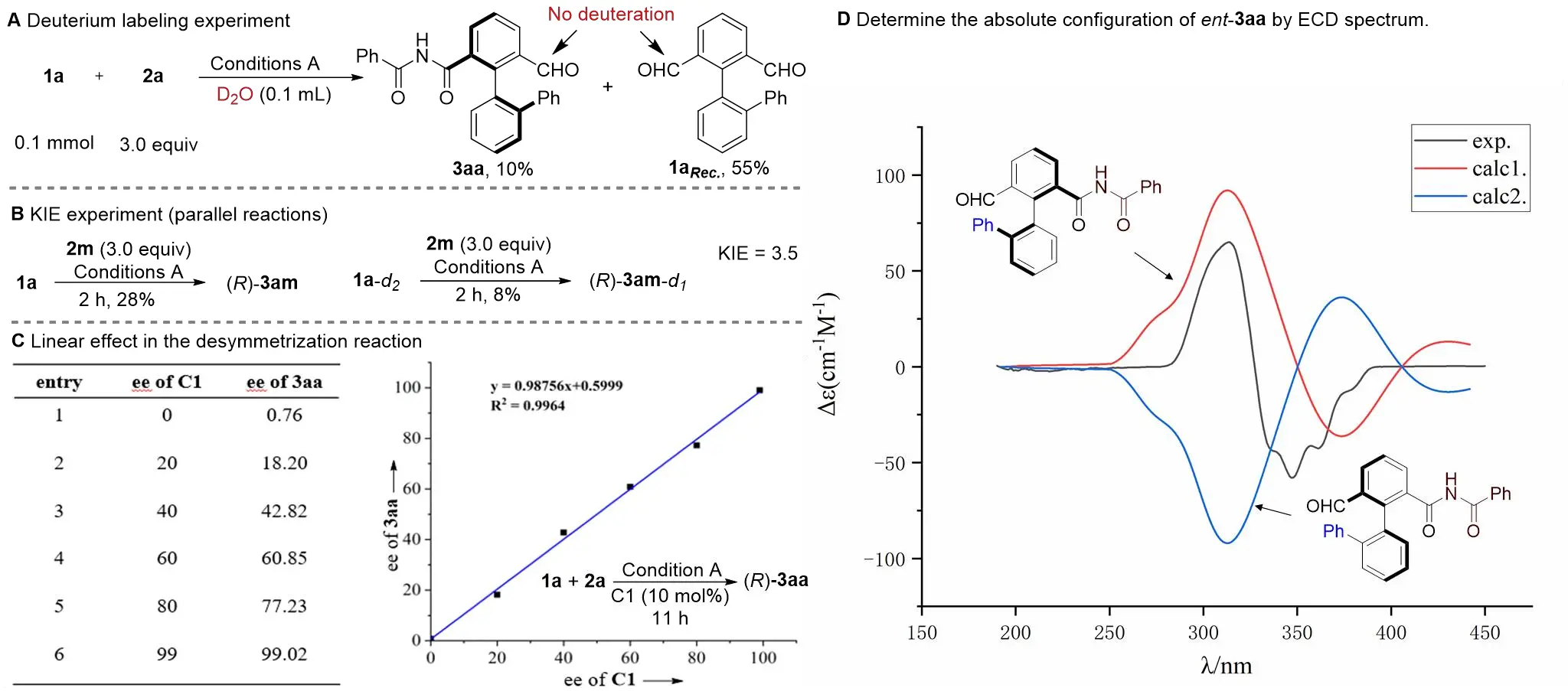

We carried out a series of mechanistic studies to elucidate the reaction pathway. Deuterium labeling experiments showed that no deuterium was incorporated into either the product or the recovered starting materials (Scheme 4A), suggesting that cleavage of the aldehyde C–H bond is irreversible under the reaction conditions. The kinetic isotope effect (KIE) was measured through parallel reactions of 1a and 1a-d₂ with 2m over 2 hours, yielding a KIE value of 3.5 (Scheme 4B). This result indicates that C–H bond cleavage is likely involved in the rate-determining step. Furthermore, the absence of nonlinear effects, as shown in Scheme 4C, supports the participation of a single chiral catalyst molecule in the enantioselectivity-determining step. The absolute configuration of the products was determined by electronic circular dichroism analysis of ent-3aa, which was assigned as S (Scheme 4D). Accordingly, the absolute configurations of all other products were assigned by analogy as R. Considering that no bisubstituted byproducts were detected in the reaction system, we conclude that the enantioselectivity is primarily governed by a desymmetrization process, although a minor contribution from kinetic resolution to the slight enhancement of the ee value cannot be entirely ruled out (Figure S1). Finally, we propose a plausible reaction mechanism, as depicted in Figure S2. It commences with the desymmetrizing nucleophilic addition of the NHC to the dialdehyde, followed by a 1,2-HAT to generate the key Breslow intermediate. This intermediate subsequently undergoes oxidation and, finally, a nucleophilic amination to construct the axially chiral imide scaffold.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, we have developed a robust and efficient method for the catalytic synthesis of axially chiral imides through NHC-catalyzed desymmetrization and amidation of axially prochiral biaryl dialdehydes. Comprehensive mechanistic studies indicate that the reaction proceeds via an irreversible, rate- and enantio-determining activation of the aldehyde, followed by oxidation and tandem C–N bond formation. This strategy proceeds under mild conditions, delivers excellent enantioselectivities (up to 99% ee), and exhibits a broad substrate scope (50 examples). The practicality of the organocatalytic amidation system is demonstrated through scalable synthesis and a variety of enantioretentive transformations. Overall, the NHC-catalyzed desymmetrization and functionalization of prochiral biaryl dialdehydes establish a versatile platform for accessing challenging axially chiral imides and their derivatives.

Supplementary materials

The supplementary material for this article is available at: Supplementary materials.

Authors contribution

Zheng G, Sun J: Conceptualization, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing.

Wu Y, Jiao K: Investigation.

Guan X, Lu X: Methodology, investigation.

Zhu L: Investigation, formal analysis.

Hu X: Investigation, resources.

Zhang Q: Writing-original draft, writing-review & editing.

Qu J: Writing-review & editing.

All authors were involved in data interpretation and discussions.

Conflicts of interest

Guangfan Zheng is an Editorial Board Member of Chiral Chemistry. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials. Other questions regarding this study can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Funding

The article was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Jilin Province (20230101047JC), National Natural Science Foundation of China (22201033, 22501260, 22501041, and 22471034) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

References

-

1. Bringmann G, Gulder T, Gulder TA, Breuning M. Atroposelective total synthesis of axially chiral biaryl natural products. Chem Rev. 2011;111(2):563-639.[DOI]

-

2. Smyth JE, Butler NM, Keller PA. A twist of nature–the significance of atropisomers in biological systems. Nat Prod Rep. 2015;32(11):1562-1583.[DOI]

-

3. Clayden J, Moran WJ, Edwards PJ, LaPlante SR. The challenge of atropisomerism in drug discovery. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48(35):6398-6401.[DOI]

-

4. Basilaia M, Chen MH, Secka J, Gustafson JL. Atropisomerism in the pharmaceutically relevant realm. Acc Chem Res. 2022;55(20):2904-2919.[DOI]

-

5. Pu L. 1,1'-Binaphthyl dimers, oligomers, and polymers: molecular recognition, asymmetric catalysis, and new materials. Chem Rev. 1998;98(7):2405-2494.[DOI]

-

6. Pu L. Enantioselective fluorescent sensors: A tale of BINOL. Acc Chem Res. 2012;45(2):150-163.[DOI]

-

7. Brunel JM. Update 1 of: BINOL: A versatile chiral reagent. Chem Rev. 2007;107(9):1-45.[DOI]

-

8. Noyori R, Takaya H. BINAP: An efficient chiral element for asymmetric catalysis. Acc Chem Res. 1990;23(10):345-350.[DOI]

-

9. Tang W, Zhang X. New chiral phosphorus ligands for enantioselective hydrogenation. Chem Rev. 2003;103(8):3029-3070.[DOI]

-

10. Teichert JF, Feringa BL. Phosphoramidites: Privileged ligands in asymmetric catalysis. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49(14):2486-2528.[DOI]

-

11. Parmar D, Sugiono E, Raja S, Rueping M. Complete field guide to asymmetric BINOL-phosphate derived Brønsted acid and metal catalysis: History and classification by mode of activation; Brønsted acidity, hydrogen bonding, ion pairing, and metal phosphates. Chem Rev. 2014;114(18):9047-9153.[DOI]

-

12. Wencel-Delord J, Panossian A, Leroux FR, Colobert F. Recent advances and new concepts for the synthesis of axially stereoenriched biaryls. Chem Soc Rev. 2015;44(11):3418-3430.[DOI]

-

13. Cheng JK, Xiang SH, Li S, Ye L, Tan B. Recent advances in catalytic asymmetric construction of atropisomers. Chem Rev. 2021;121(8):4805-4902.[DOI]

-

14. Cheng JK, Xiang SH, Tan B. Organocatalytic enantioselective synthesis of axially chiral molecules: Development of strategies and skeletons. Acc Chem Res. 2022;55(20):2920-2937.[DOI]

-

15. Wu YJ, Liao G, Shi BF. Stereoselective construction of atropisomers featuring a C–N chiral axis. Green Synth Catal. 2022;3(2):117-136.[DOI]

-

16. Roos CB, Chiang CH, Murray LAM, Yang D, Schulert L, Narayan AR.Stereodynamic strategies to induce and enrich chirality of atropisomers at a late stage. Chem Rev. 2023;123(17):10641-10727.[DOI]

-

17. Xiang SH, Ding WY, Wang YB, Tan B. Catalytic atroposelective synthesis. Nat Catal. 2024;7(5):483-498.[DOI]

-

18. Chen J, Gong X, Li J, Li Y, Ma J, Hou C, et al. Carbonyl catalysis enables a biomimetic asymmetric Mannich reaction. Science. 2018;360(6396):1438-1442.[DOI]

-

19. Xiao X, Zhao B. Vitamin B6-based biomimetic asymmetric catalysis. Acc Chem Res. 2023;56(9):1097-1117.[DOI]

-

20. Zhou T, Qian PF, Li JY, Zhou YB, Li HC, Chen HY. et al. Efficient synthesis of sulfur-stereogenic sulfoximines via Ru (II)-catalyzed enantioselective C–H functionalization enabled by chiral carboxylic acid. J Am Chem Soc. 2021;143(18):6810-6816.[DOI]

-

21. Li JY, Xie PP, Zhou T, Qian PF, Zhou YB, Li HC, et al. Ir (III)-catalyzed asymmetric C–H activation/annulation of sulfoximines assisted by the hydrogen-bonding interaction. ACS Catal. 2022;12(15):9083-9091.[DOI]

-

22. Zhou YB, Zhou T, Qian PF, Li JY, Shi BF. Synthesis of sulfur-stereogenic sulfoximines via Co (III)/chiral carboxylic acid-catalyzed enantioselective C–H Amidation. ACS Catal. 2022;12(15):9806-9811.[DOI]

-

23. Qian PF, Zhou T, Li JY, Zhou YB, Shi BF. Ru (II)/Chiral Carboxylic Acid-Catalyzed Asymmetric [4 + 3] Annulation of Sulfoximines with α,β-Unsaturated Ketones. ACS Catal. 2022;12(22):13876-13883.[DOI]

-

24. Shen X, Jones GO, Watson DA, Bhayana B, Buchwald SL. Enantioselective synthesis of axially chiral biaryls by the Pd-catalyzed Suzuki-Miyaura reaction: Substrate scope and quantum mechanical investigations. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(32):11278-11287.[DOI]

-

25. Jia ZJ, Merten C, Gontla R, Daniliuc CG, Antonchick AP, Waldmann H. General enantioselective C−H activation with efficiently tunable cyclopentadienyl ligands. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56(9):2429-2434.[DOI]

-

26. Shaaban S, Li H, Otte F, Strohmann C, Antonchick AP, Waldmann H. Enantioselective synthesis of five-membered-ring atropisomers with a chiral Rh (III) complex. Org Lett. 2020;22(23):9199-9202.[DOI]

-

27. Liang H, Zhu G, Pu X, Qiu L. Copper-catalyzed enantioselective C–H arylation between 2-arylindoles and hypervalent iodine reagents. Org Lett. 2021;23(23):9246-9250.[DOI]

-

28. Jiang BY, Zhou G, Jiang AL, Zhou T, Shi BF. Synthesis of axially chiral biaryl-2-carboxamides through Pd (ii)-catalyzed atroposelective C–H olefination. Org Chem Front. 2024;11(13):3710-3716.[DOI]

-

29. Zhang Q, Xue X, Hong B, Gu Z. Torsional strain inversed chemoselectivity in a Pd-catalyzed atroposelective carbonylation reaction of dibenzothiophenium. Chem Sci. 2022;13(13):3761-3765.[DOI]

-

30. Bugaut X, Glorius F. Organocatalytic umpolung: N-heterocyclic carbenes and beyond. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41(9):3511-3522.[DOI]

-

31. Hopkinson MN, Richter C, Schedler M, Glorius F. An overview of N-heterocyclic carbenes. Nature. 2014;510(7506):485-496.[DOI]

-

32. Menon RS, Biju AT, Nair V. Recent advances in employing homoenolates generated by N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) catalysis in carbon–carbon bond-forming reactions. Chem Soc Rev. 2015;44(15):5040-5052.[DOI]

-

33. Flanigan DM, Romanov-Michailidis F, White NA, Rovis T. Organocatalytic reactions enabled by N-heterocyclic carbenes. Chem Rev. 2015;115(17):9307-9387.[DOI]

-

34. Murauski KJR, Jaworski AA, Scheidt KA. A continuing challenge: N-heterocyclic carbene-catalyzed syntheses of γ-butyrolactones. Chem Soc Rev. 2018;47(5):1773-1782.[DOI]

-

35. Chen XY, Gao ZH, Ye S. Bifunctional N-heterocyclic carbenes derived from l-pyroglutamic acid and their applications in enantioselective organocatalysis. Acc Chem Res. 2020;53(3):690-702.[DOI]

-

36. Bellotti P, Koy M, Hopkinson MN, Glorius F. Recent advances in the chemistry and applications of N-heterocyclic carbenes. Nat Rev Chem. 2021;5(10):711-725.[DOI]

-

37. Liu K, Schwenzer M, Studer A. Radical NHC catalysis. ACS Catal. 2022;12(19):11984-11999.[DOI]

-

38. Zhang Z, Huang S, Gao F, Lu G, Yan X. Photoredox decarboxylative acylation of carboxylic acid by 4-acyl-1,2,3-triazoliums. Green Synth Catal. 2024.[DOI]

-

39. Zhang M, Yang X, Peng X, Li X, Jin Z. Asymmetric construction of axial and planar chirality with N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) organocatalysis. Sci China Chem. 2025;68:815-825.[DOI]

-

40. Chakraborty S, Barik S, Biju AT. N-Heterocyclic carbene (NHC) organocatalysis: From fundamentals to frontiers. Chem Soc Rev. 2025;54(3):1102-1124.[DOI]

-

41. Ling D, Ran Y, Yang F, Yang X, Wu X, Ren SC, et al. Advances in N-heterocyclic carbene organocatalysis from 2015 to 2024. Chem Soc Rev. 2025.[DOI]

-

42. Oorissov A, Davies TQ, Ellis SR, Fleming TA, Richardson MSW, Dixon DJ. Organocatalytic enantioselective desymmetrisation. Chem Soc Rev. 2016;45(20):5474-5540.[DOI]

-

43. Zeng XP, Cao ZY, Wang YH, Zhou F, Zhou J. Catalytic enantioselective desymmetrization reactions to all-carbon quaternary stereocenters. Chem Rev. 2016;116(12):7330-7396.[DOI]

-

44. Saint-Denis TG, Zhu RY, Chen G, Wu QF, Yu JQ. Enantioselective C(sp3)‒H bond activation by chiral transition metal catalysts. Science. 2018;359(6377):eaao4798.[DOI]

-

45. Carmona JA, Rodríguez-Franco C, Fernández R, Hornillos V, Lassaletta JM. Atroposelective transformation of axially chiral (hetero)biaryls. From desymmetrization to modern resolution strategies. Chem Soc Rev. 2021;50(5):2968-2983.[DOI]

-

46. Moon J, Kim S, Lee S, Cho HA, Kim A, Ham MK, et al. Recent advances in catalytic desymmetrization for the synthesis of axially chiral biaryls. ChemCatChem. 2024;16(19):e202400690.[DOI]

-

47. Liu J, Zhou M, Deng R, Zheng P, Chi YR. Chalcogen bond-guided conformational isomerization enables catalytic dynamic kinetic resolution of sulfoxides. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):4793.[DOI]

-

48. Zhou M, Liu J, Deng R, Wang Q, Wu S, Zheng P, Chi YR. Construction of tetrasubstituted silicon-stereogenic silanes via conformational isomerization and N-heterocyclic carbene-catalyzed desymmetrization. ACS Catal. 2022;12(13):[DOI]

-

49. Liu J, Deng R, Liang X, Zhou M, Zheng P, Chi YR. Carbene-catalyzed and pnictogen bond-assisted access to PIII-stereogenic compounds. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2024;63(28):e202404477.[DOI]

-

50. Lv X, Xu J, Sun C, Su F, Cai Y, Jin Z, et al. Access to planar chiral ferrocenes via N-heterocyclic carbene-catalyzed enantioselective desymmetrization reactions. ACS Catal. 2022;12(4):2706-2713.[DOI]

-

51. Dočekal V, Koucký F, Císařová I, Veselý J. Organocatalytic desymmetrization provides access to planar chiral [2.2]paracyclophanes. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):3090.[DOI]

-

52. Shee S, Shree Ranganathappa S, Gadhave MS, Gogoi R, Biju AT. Enantioselective synthesis of C–O axially chiral diaryl ethers by NHC-catalyzed atroposelective desymmetrization. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2023;62(52):e202311709.[DOI]

-

53. Zhou BA, Li XN, Zhang CL, Wang ZX. Ye S. Enantioselective synthesis of axially chiral diaryl ethers via NHC catalyzed desymmetrization and following resolution. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2023;63(4):e202314228.[DOI]

-

54. Wu Y, Li M, Sun J, Zheng G, Zhang Q. Synthesis of axially chiral aldehydes by N-heterocyclic-carbene-catalyzed desymmetrization followed by kinetic resolution. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2022;61(14):e202117340.[DOI]

-

55. Wu YT, Guan X, Zhao H, Li M, Liang T, Sun J, et al. Synthesis of axially chiral diaryl ethers via NHC-catalyzed atroposelective esterification. Chem Sci. 2024;15(12):4564.[DOI]

-

56. Zhao W, Liu J, He X, Jiang H, Lu L, Xiao W. N-Heterocyclic carbene (NHC)-catalyzed desymmetrization of biaryldialdehydes to construct axially chiral aldehydes. Chin J Org Chem. 2022;42(8):2504.[DOI]

-

57. Cai Y, Lv Y, Shu L, Jin Z, Chi YR, Li T. Access to axially chiral aryl aldehydes via carbene-catalyzed nitrile formation and desymmetrization reaction. Research. 2024;7:0293.[DOI]

-

58. Shee S, Ramachandran D, Gogoi R, Biju AT. Dynamic kinetic resolution approach to C–O axially chiral benzonitriles via N-Heterocyclic carbene-catalyzed atroposelective imine umpolung. ACS Catal. 2025;15(15):13157.[DOI]

-

59. Yuan B, Page A, Worrall CP, Escalettes F, Willies SC, McDouall JJW, et al. Biocatalytic desymmetrization of an atropisomer with both an enantioselective oxidase and ketoreductases. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49(39):7010-7013.[DOI]

-

60. Staniland S, Yuan B, Giménez‐Agulló N, Marcelli T Willies SC, Grainger DM, et al. Enzymatic desymmetrising redox reactions for the asymmetric synthesis of biaryl atropisomers. Chem Eur J. 2014;20(41):13084-13088.[DOI]

-

61. Jiang H, He XK, Jiang X, Zhao W, Lu LQ, Cheng Y, et al. Photoinduced cobalt-catalyzed desymmetrization of dialdehydes to access axial chirality. J Am Chem Soc. 2023;145(12):6944-6952.[DOI]

-

62. Dai L, Liu Y, Xu Q, Wang M, Zhu Q, Yu P, et al. A dynamic kinetic resolution approach to axially chiral diaryl ethers by catalytic atroposelective transfer hydrogenation. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2023;135(7):e202216534.[DOI]

-

63. Huang F, Tao LF, Liu JY, Qian LH, Liao JY. Diastereo- and enantioselective synthesis of biaryl aldehydes bearing both axial and central chirality. Chem Commun. 2023;59(30):4487-4490.[DOI]

-

64. Liang T, Wu Y, Sun J, Li M, Zhao H, Zhang J, et al. Visible light-mediated cobalt and photoredox dual-catalyzed asymmetric reductive coupling for axially chiral secondary alcohols. Chin J Chem. 2023;41(23):3253-3260.[DOI]

-

65. Wang Y, Song RP, Li XY, Chen WL, Tian Y, Zhang SH, et al. Catalytic asymmetric reductive amination for axially chiral aryl aldehydes via desymmetrization/kinetic resolution cascade. Org Lett. 2024;26(34):7161-7165.[DOI]

-

66. Ye M, Li C, Xiao D, Qu G, Yuan B, Sun Z. Atroposelective synthesis of aldehydes via alcohol dehydrogenase-catalyzed stereodivergent desymmetrization. JACS Au. 2024;4(2):411-418.[DOI]

-

67. Lin L, Zhu L, Teng B, Xia J, Sun J, Zheng G, et al. Cobalt-catalyzed enantioselective [2+2+2] cycloaddition/electrocyclic ring opening cascade of aldehydes and diynes. Sci China Chem. 2025;68:1-10.[DOI]

-

68. Yang J, Du Y, Cheng F, An K, Hu Y, Li Z. Construction of axially chiral dialdehydes via rhodium-catalyzed enantioselective C−H amidation. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2025;64(11):e202421412.[DOI]

-

69. Li T, Mou C, Qi P, Peng X, Jiang S, Hao G, et al. N-heterocyclic carbene-catalyzed atroposelective annulation for access to thiazine derivatives with C−N axial chirality. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2021;133(17):9448-9453.[DOI]

-

70. Ma R, Wang X, Zhang Q, Chen L, Gao J, Feng J, et al. Atroposelective synthesis of axially chiral 4-aryl α-carbolines via N-heterocyclic carbene catalysis. Org Lett. 2021;23(11):4267-4272.[DOI]

-

71. Jin J, Huang X, Xu J, Li T, Peng X, Zhu X, et al. Carbene-catalyzed atroposelective annulation and desymmetrization of urazoles. Org Lett. 2021;23(10):3991-3996.[DOI]

-

72. Chu Y, Wu M, Hu F, Zhou P, Cao Z, Hui XP. N-heterocyclic carbene-catalyzed atroposelective synthesis of pyrrolo [3,4-b] pyridines with configurationally stable C–N axial chirality. Org Lett. 2022;24(21):3884-3889.[DOI]

-

73. Barik S, Das RC, Balanna K, Biju AT. Kinetic resolution approach to the synthesis of C–N axially chiral N-aryl aminomaleimides via NHC-catalyzed [3 + 3] annulation. Org Lett. 2022;24(29):5456-5461.[DOI]

-

74. Lv Y, Luo G, Liu Q, Jin Z, Zhang X, Chi YR. Catalytic atroposelective synthesis of axially chiral benzonitriles via chirality control during bond dissociation and CN group formation. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):36.[DOI]

-

75. Balanna K, Barik S, Barik S, Shee S, Manoj N, Gonnade RG, et al. N-heterocyclic carbene-catalyzed atroposelective synthesis of N–N axially chiral 3-amino quinazolinones. ACS Catal. 2023;13(13):8752-8759.[DOI]

-

76. Barik S, Ranganathappa SS, Biju AT. N-heterocyclic carbene-catalyzed atroposelective synthesis of N-Aryl phthalimides and maleimides via activation of carboxylic acids. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):5755.[DOI]

-

77. Song C, Pang C, Deng Y, Cai H, Gan X, Chi YR. Catalytic N-acylation for access to N–N atropisomeric N-aminoindoles: Choice of acylation reagents and mechanistic insights. ACS Catal. 2024;14(9):6926-6935.[DOI]

-

78. Wang L, Ma R, Sun J, Zheng G, Zhang Q. NHC and visible light-mediated photoredox co-catalyzed 1, 4-sulfonylacylation of 1, 3-enynes for tetrasubstituted allenyl ketones. Chem Sci. 2022;13(11):3169-3175.[DOI]

-

79. Wang L, Sun J, Xia J, Li M, Zhang L, Ma R, et al. Visible light-mediated NHCs and photoredox co-catalyzed radical 1, 2-dicarbonylation of alkenes for 1, 4-diketones. Sci China Chem. 2022;65(10):1938-1944.[DOI]

-

80. Li M, Song X, Lu X, Xia J, Zheng G, Zhang Q, Visible light-mediated 1,3-acylative chlorination of cyclopropanes employing benzoyl chloride as bifunctional reagents in NHC catalysis. Sci China Chem. 2025;68(8):3628-3635.[DOI]

-

81. Sun J, Wang L, Zheng G, Zhang Q. Recent advances in three-component radical acylative difunctionalization of unsaturated carbon-carbon bonds. Org Chem Front. 2023;10(18):4488-4515.[DOI]

-

82. Xia J, Ma R, Wang L, Sun J, Zheng G, Zhang Q. NHC and photoredox catalysis dual-catalyzed 1,4-mono-/di-fluoromethylative acylation of 1, 3-enynes. Org Che. Front. 2024;11(11):3089-3099.[DOI]

-

83. Li M, Wu Y, Song X, Sun J, Zhang Z, Zheng G, et al. Visible light-mediated organocatalyzed 1,3-aminoacylation of cyclopropane employing N-benzoyl saccharin as bifunctional reagent. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):8930.[DOI]

-

84. Guo Y, Liu X, Hu L, Xia J, Li Y, Zhu L, et al. Visible-light-driven cobalt-catalyzed assembly of indole-alcohols bearing concurrent axial and central chiralities via dynamic kinetic resolution. ACS Cat. 2025;15:18305-18314.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite