Abstract

Redoxins, oxidoreductases of the thioredoxin (Trx) family, are important regulators of signaling processes. The Trx family is characterized by the Trx fold consisting of a four-stranded β-sheet surrounded by three-four α-helices. This article mainly focuses on mammalian Trxs, glutaredoxins, and peroxiredoxins, herein referred to as redoxins. This review article summarizes the current knowledge on redoxin-driven processes related to ferroptosis, a non-apoptotic cell death mechanism based on uncontrolled oxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids in membranes. To a great extent, the formation of these lipid hydroperoxides depend on the non-enzymatic formation of hydroxyl radicals, the product of the Fenton reaction between hydrogen peroxide and redox active iron. Redoxins are regulators of both redox and iron homeostasis, and some redoxins use lipid hydroperoxides directly as substrates. This review article aims to increase the recognition of redoxins as potential regulators of ferroptosis in both physiological and pathological conditions, while also promoting research to address the numerous gaps in cell specificity and the molecular mechanisms influencing ferroptotic pathways.

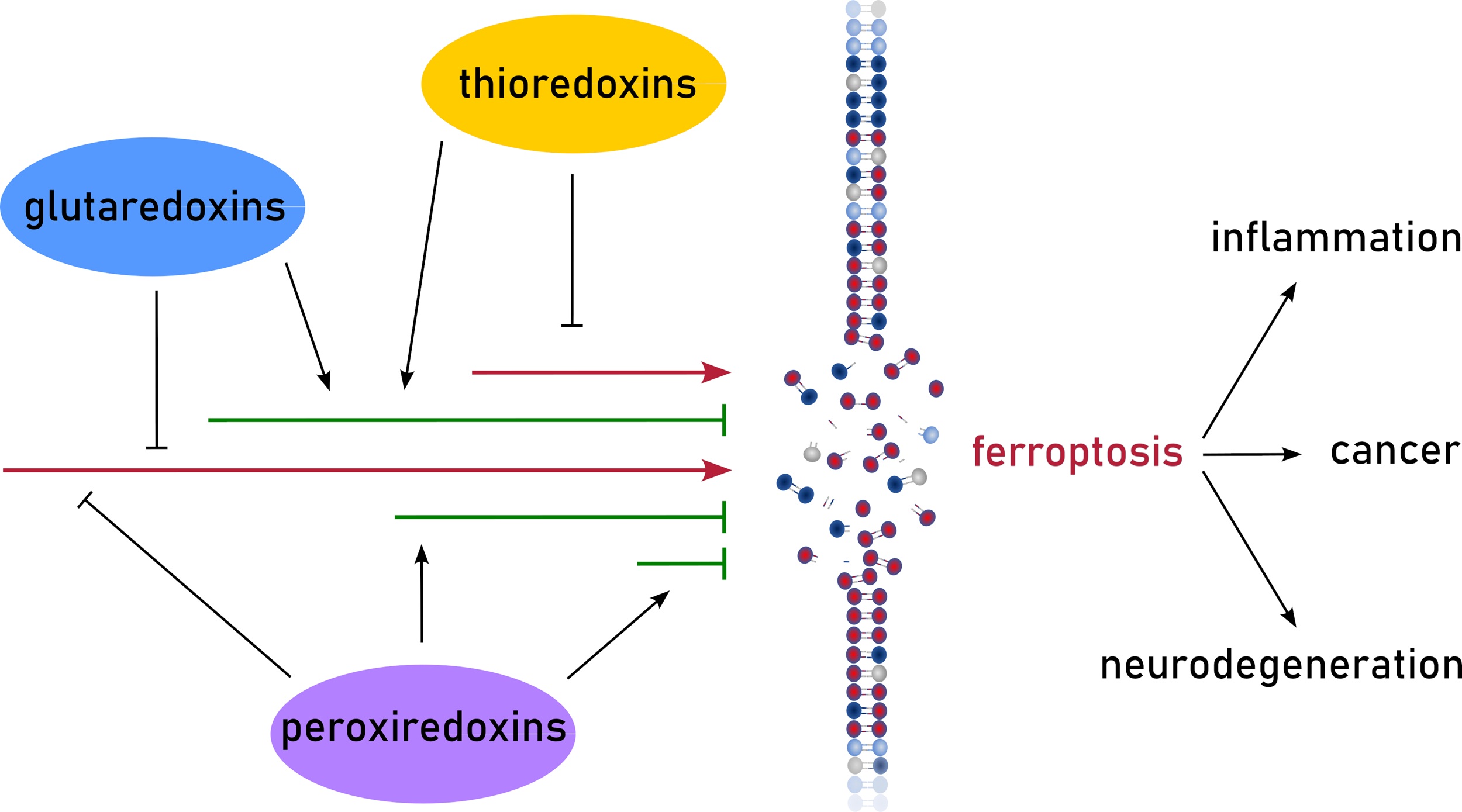

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

1. Redoxins

Oxidative modifications of cysteinyl side chains alter the function of numerous proteins that contain cysteines of structural importance, within their catalytic centers or as part of interaction interfaces. Primarily, the redox state of these thiol groups is controlled by the oxidoreductases of the thioredoxin (Trx) family, to which Trxs, glutaredoxins (Grxs), and peroxiredoxins (Prxs) belong[1,2]. These enzyme families are often referred to as redoxins. Members of the Trx family share a common structural motif known as the Trx fold. In its most basic form, found in some bacterial Grxs, this fold consists of three α-helices surrounding a central core made up of a four-stranded β-sheet[3]. In many Grxs of higher organisms, Trxs, and particularly Prxs, this motif is expanded by additional α-helices or β-strands. The redox-active site of the proteins is located on a loop connecting strand β1 and helix α1 and consists of one or two cysteine residues. Trxs and Grxs are thiol-disulfide oxidoreductases, whereas Prxs mainly reduce peroxides.

1.1 Trxs

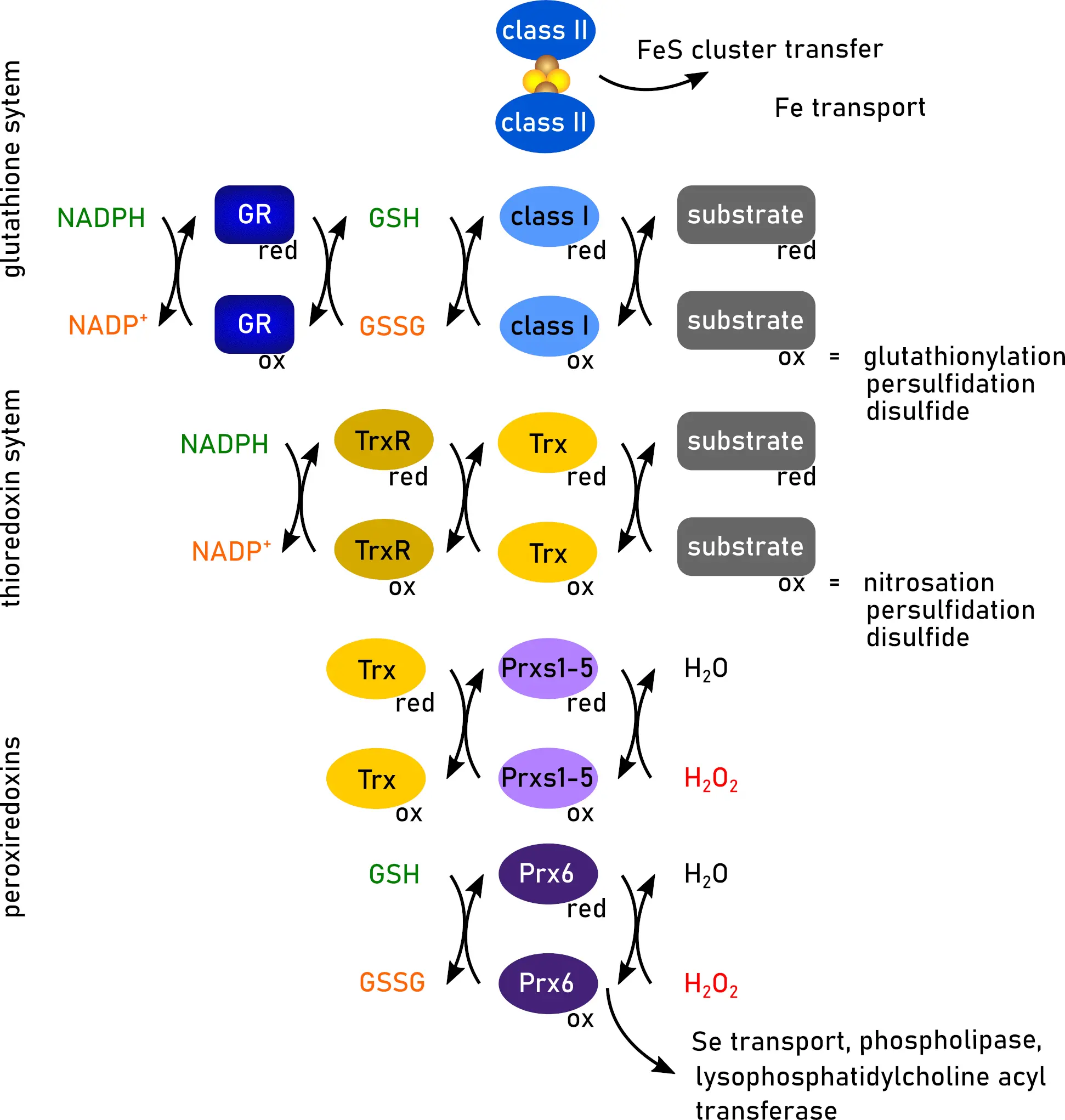

Trxs were originally identified as the electron donor for ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) in E. coli[4]. Trx proteins undergo reversible protein-disulfide exchange reactions with their substrates[1,5]. The reaction is initiated by a nucleophilic attack of the more N-terminal cysteine residue of the CGPC consensus active site on the target disulfide. The resulting mixed disulfide between Trx and the substrate is reduced by the more C-terminal active site cysteine, thus completing the exchange reaction. The disulfide in the active site of Trxs can subsequently be reduced by a dedicated reductase, i.e., Trx reductase (TrxR), at the expense of reduced nicotinamide adenin dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH). Mammalian TrxRs are homodimeric selenoenzymes of 55-60 kDa in a head-to-tail conformation, with every subunit containing a flavin adenine dinucleotide, an NADPH-binding domain, and the C-terminal active site motif GCUC. Together, Trx and TrxR are often referred to as the “thioredoxin system” (Figure 1)[1,5].

Figure 1. Functions of redoxins. Trx, glutaredoxins (class I and class II), and Prx display overlapping and different functions. Created in inkscape. Trx: thioredoxin; Prx: peroxiredoxin; GR: glutathione reductase; GSH: glutathione; GSSG: GSH disulfide; NADPH: reduced nicotinamide adenin dinucleotide phosphate; NADP+: oxidized nicotinamide adenin dinucleotide phosphate; red: reduced; ox: oxidized.

Mammalian genomes encode two Trx systems. Trx1 and TrxR1 make up the cytosolic system. Trx1 has also been shown to translocate into the nucleus in response to various stimuli and can be secreted[6,7]. In the mitochondria, Trx2 and TrxR2 are present[8]. Additionally, there is a third testis-specific Trx reductase, TrxR3, also known as thioredoxin glutathione reductase, which is primarily expressed in germ cells and contains a class I Grx domain[9] (see below). Trx1 and Trx2 share 35% sequence homology and exhibit similar catalytic properties in vitro[10]. Notably, mitochondrial Trx2 contains the active site motif found in Trx1 but lacks additional structural cysteines, proposed to modulate its function as regulatory sites[11,12]. Moreover, one of the extra cysteine residues, Cys73, is the second ligand of a Fe2S2 cluster bound by Trx1[13]. The other ligand is the active site Cys32. The assembly/disassembly of the FeS-Trx1 dimer fine tunes the activity of IRP1, a main regulator of iron homeostasis acting on the posttranslational level[13-15]. Whereas IRP1 with coordinated FeS cluster functions as aconitase, iron deficiency activates the mRNA binding activity of IRP1. The cysteines coordinating the FeS cluster are the same that bind specific iron-responsive elements (IREs) formed by mRNAs encoding proteins involved in iron homeostasis. However, to bind IREs, these cysteines need to be reduced by Trx1[13,16].

1.2 Grxs

Grxs were initially identified as alternative electron donors in essential metabolic processes, foremost the reduction of ribonucleotides for DNA synthesis[17,18]. The members of the first class of Grxs, often referred to as class I or dithiol Grxs, share a common CPYC motif in their active sites. The two cysteines in this motif catalyze glutathione (GSH)-dependent thiol-disulfide exchange reactions, i.e., the reduction of protein disulfides and, with high specificity, reversible (de-)glutathionylation[19] Oxidized Grxs are reduced by GSH, the resulting GSH disulfide (GSSG) by glutathione reductase (GR) using NADPH as electron source[20]. A subgroup of the class I Grxs features a variation in the active site where the proline residue is replaced by serine or glycine residues (C(S/G)YC). These Grxs can coordinate a Fe2S2 cluster at the interface of a dimer formed by two Grxs, using the two N-terminal active site thiols and the thiols of two non-covalently bound GSH molecules as ligands[21,22].

Mammalian cells contain four Grxs: Grx1, Grx2, Grx3 (previously known as PICOT), and Grx5 as stated in a previous review[20]. Grx1, a 12-kDa class I Grx with CPYC active site, is mainly found in the cytosol but can also enter the nucleus or be exported from the cell[23,24]. Grx2, the second class I Grx is targeted to mitochondria[25], but has cancer/testis- and differentiation-specific isoforms[26,27] located in the cytosol and nucleus. Grx2 contains the CSYC active site, allowing it to accept electrons from TrxR[28] and to form the dimeric Fe2S2-bridged holo-complex[21,29]. Grx3 is a 38-kDa class II Grx that features two N-terminal Grx domains with the active site CGFS and a C-terminal Trx domain. It is found in the cytosol and nucleus and has been linked to protein kinase C-θ signaling[30] and iron homeostasis[31]. Grx5, a 16-kDa class II Grx, is targeted to mitochondria and is critical for iron-sulfur cluster biogenesis[32,33].

Class I Grxs can reduce protein disulfides in a similar dithiol reaction mechanism as Trxs[34]. The resulting disulfide in the Grx active site, however, is not reduced by a dedicated reductase, but by two molecules of GSH that reduce the Grx via a Grx active site and GSH (Grx-S-SG) mixed disulfide intermediate (Figure 1). In contrast, the reversible (de-)glutathionylation reaction involves only the more N-terminal cysteine residue in the active site, and is thus referred to as the monothiol reaction mechanism. In summary, the reaction begins when the thiolate of this cysteine residue nucleophilically attacks the GSH moiety of the glutathionylated protein. This attack results in the reduction of the protein substrate and the formation of a mixed disulfide bond between the N-terminal cysteine residue of the Grx-S-SG. Subsequently, this disulfide bond is reduced by a second molecule of GSH. The mechanism for the reduction of this mixed disulfide involves a second GSH binding site on Grxs, which is believed to activate GSH as the reducing agent[35]. Details on both reaction mechanisms were discussed in a review by Lillig and Berndt[34]. Originally only described for the reduction of GSH-mixed disulfides, the monothiol reaction mechanism may also be functional for the reduction of certain protein disulfides, e.g., mammalian RNR and engineered GFP variants[36,37]. Notably, all these reaction steps are reversible, with their direction determined by thermodynamic restrains, such as the current redox potential of the GSH/GSSG redox couple.

The second class of Grxs, known as class II or monothiol Grxs, features a consensus CGFS active site motif. These proteins play a crucial role in iron metabolism, particularly in the biogenesis of FeS clusters, as well as in the transport of iron[38,39] (Figure 1). The ability of CGFS-type Grxs to bind a Fe2S2 cluster in a similar manner to class I FeS Grxs[40] is essential for these functions[41]; however, neither of the FeS-Grxs from both classes can compensate for the loss of the other. Both classes of Grxs share a similar basic structure and possess all the necessary motifs required to interact with GSH moieties in a highly similar manner[41]. Class-specific differences in the loop preceding the active site determine the functions of both classes of Grxs[42,43].

1.3 Prxs

Prxs are 20-30 kDa proteins that exist in different isoforms across various cellular compartments and can make up to 1% of soluble cellular proteins in mammalian cells[44]. Alongside their peroxidase activity, they may also function as molecular chaperones[45] and specific oxidases in signaling pathways through redox relay reactions[46,47].

Mammalian cells contain six Prxs, classified into three groups: 2-Cys Prxs (Prx1-4), atypical 2-Cys Prx (Prx5), and 1-Cys Prx (Prx6). The 2-Cys Prxs form dimers during the reaction cycle and adopt decameric complexes, whereas the atypical 2-Cys and 1-Cys Prxs do not form dimers (as stated in previous reviews[48,49]). Prx1 is primarily located in the cytosol, nucleus, and peroxisomes, but it can also be detected in serum[50]. Prx2 is present in the cytosol and nucleus and has the ability to bind to membranes[51]. Prx3 is mainly restricted to mitochondria[52], but is also found at the plasma membrane[53], whereas Prx4 is found in the cytosol, the endoplasmic reticulum and as secreted protein[54]. Prx5 is located in the cytosol, mitochondria, and peroxisomes[52], while Prx6 is predominantly in the cytosol[55]. Knockout of Prxs is generally not lethal; however, it results in increased levels of hydrogen peroxide and defects in certain cellular pathways.

The reduction of hydrogen peroxide by Prxs proceeds through a conserved catalytic cycle[49,56,57]. In the first step, the peroxidatic cysteine performs a nucleophilic attack on H2O2 and is partially reduced, resulting in a water molecule and a sulfenic acid intermediate at the N-terminal peroxidatic cysteine. This intermediate is then reduced by a second resolving cysteine residue located outside the classical active site, forming a disulfide bond. Typical 2-Cys Prxs (i.e., human Prx 1-4) feature a resolving cysteine at the C-terminus and form intermolecular disulfides between adjacent subunits, while atypical 2-Cys Prxs (i.e., human Prx5) form intramolecular disulfides. Both types are primarily reduced by Trxs. In contrast, 1-Cys Prx family members (i.e., human Prx6) lack a resolving cysteine and are likely reduced by GSH (Figure 1). Prx6 also functions as a phospholipase, a lysophosphatidylcholine acyl transferase, and a selenium transfer and utilization factor (Figure 1)[58-60]. By reaction of the sulfenic acid intermediate, Prxs can become over-oxidized to sulfinic and sulfonic acids. Sulfinic acid formation is typically regarded irreversible. The only known reductase for sulfinic acids is specific for Prxs[61]. These sulfiredoxin (Srx) use ATP to convert sulfinic acids via phosphoryl esters into thiosulfinates[62]. Srx then reduces these intermediates back to sulfenic acids, a process dependent on disulfide bond formation[63].

2. Ferroptosis

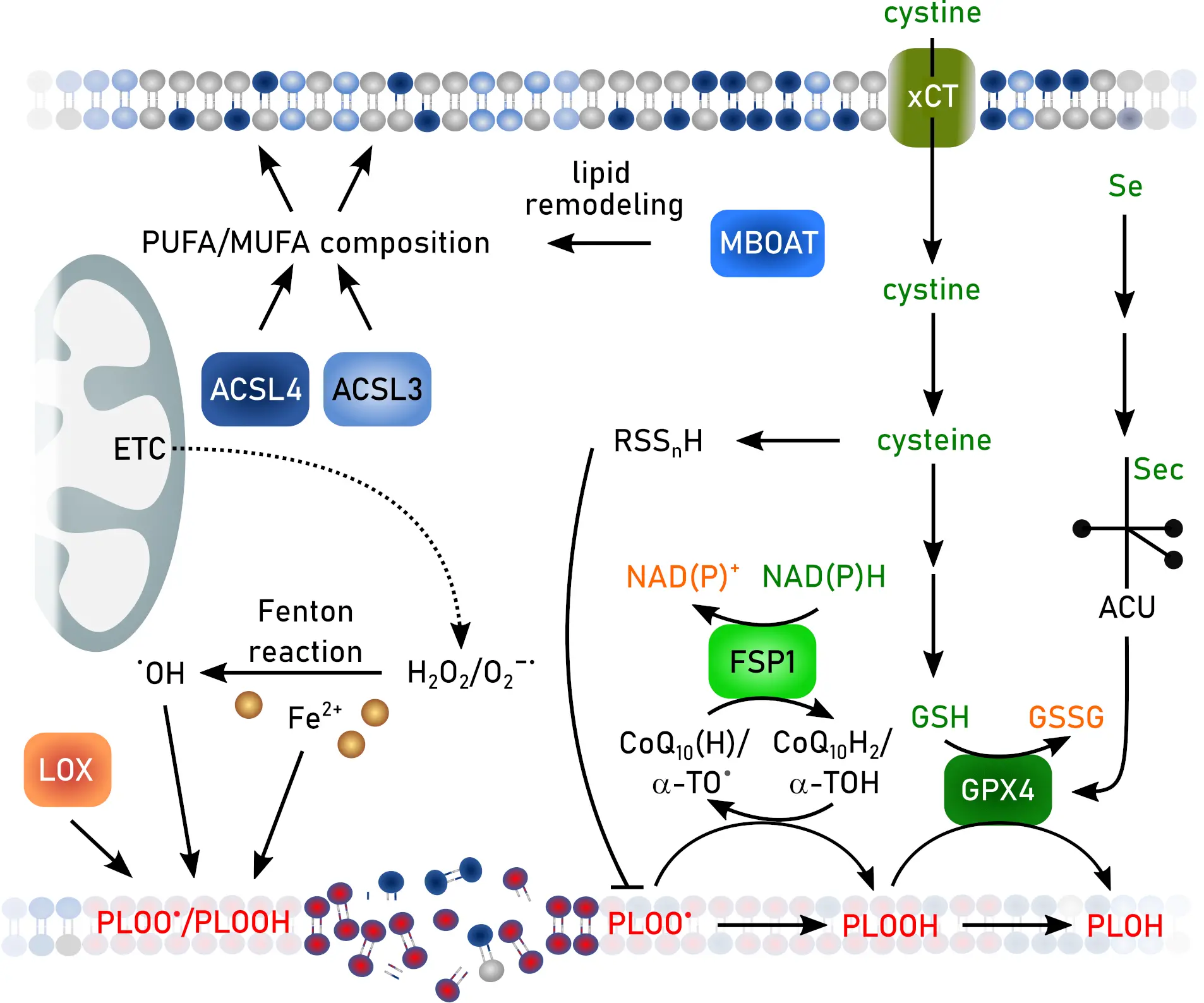

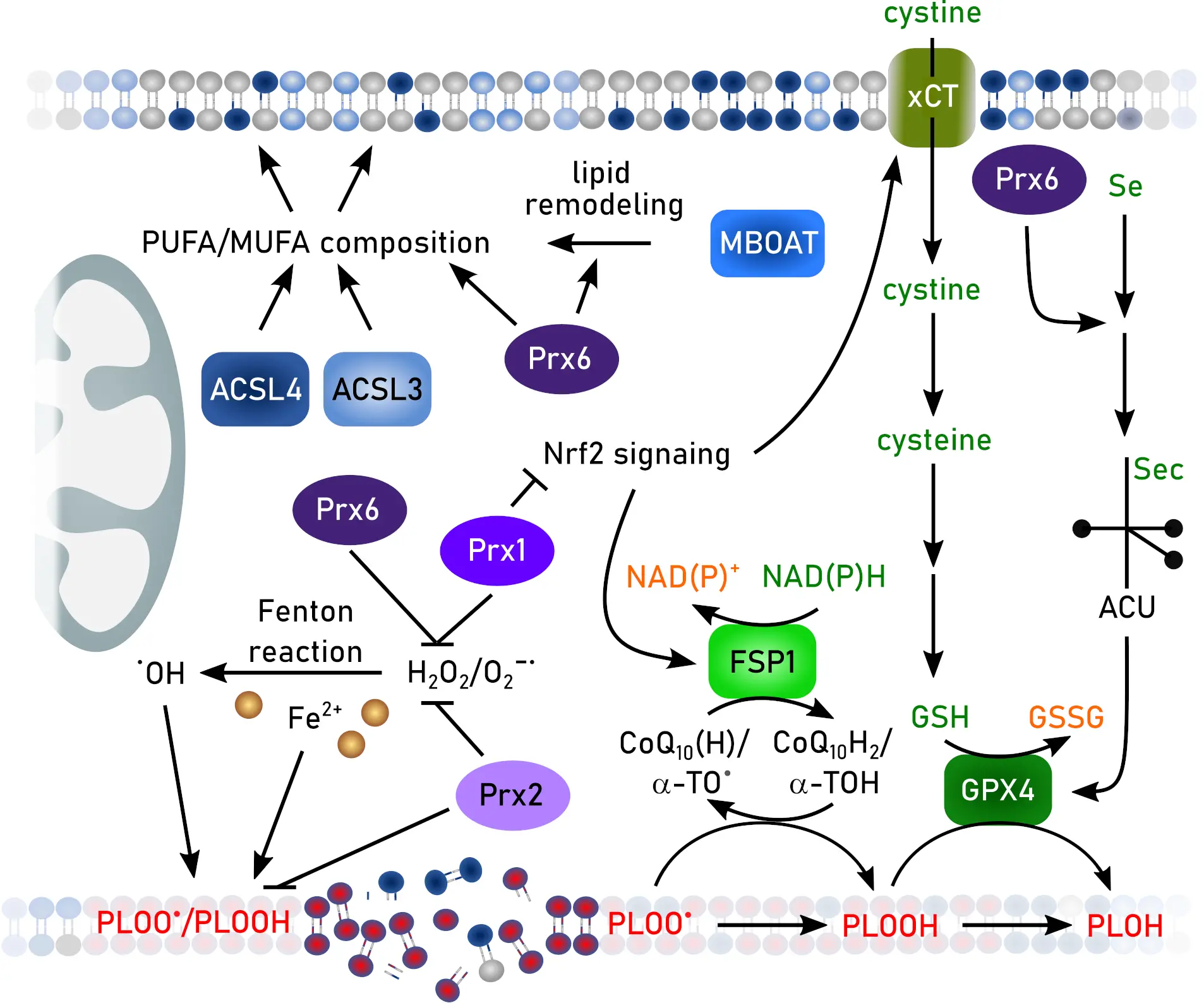

Ferroptosis is a regulated form of cell death characterized by uncontrolled iron-dependent peroxidation of (phospho)lipids[64,65] (Figure 2), representing a pivotal aspect of redox cell biology and a promising avenue for therapeutic intervention[65-67]. The following section introduces the key aspects of ferroptotic cell death.

Figure 2. Hallmarks of ferroptosis. Created in inkscape. ACSL3: synthetase long-chain-fatty-acid family member 3; ACSL4: acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain-fatty-acid family member 4; α-TO: α-tocopherol/vitamin E; CoQ10: co-enzyme Q10; ETC: electron transport chain; FSP: ferroptosis suppressor protein; GSH: glutathione; GSSG: GSH disulfide; GPX: GSH peroxidase; LOX: lipid oxidase; MBOAT: membrane-bound O-acetyltransferase; MUFA: mono-unsaturated fatty acid; NAD(P)H: reduced nicotinamide adenin dinucleotide (phosphate); NAD(P)+: oxidized nicotinamide adenin dinucleotide (phosphate); PUFA: poly-unsaturated fatty acid.

2.1 Iron and the Fenton-reaction-driven initiation of lipid oxidation

At the core of ferroptosis lies the redox reactivity of iron. Ferrous iron (Fe2+) catalyzes the Fenton reaction with hydrogen peroxide, generating hydroxyl radicals (•OH) that extract hydrogen atoms from bis-allylic carbons of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). The resulting lipid radicals (L•) react with oxygen to form lipid peroxyl radicals (LOO•), propagating chain reactions that yield lipid hydroperoxides (LOOH)[68]. Subsequently, this leads to oxidative membrane damage, rupture, and ferroptotic cell death. Lipophilic radical-trapping antioxidants such as α-tocopherol (vitamin E) can interrupt this chain reaction by donating hydrogen atoms to lipid peroxyl radicals, thereby preventing cells from undergoing ferroptosis[69].

2.2 Glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4): the master regulator of ferroptosis

The central suppressor of ferroptosis is GPX4, a selenoprotein that reduces phospholipid hydroperoxides to their corresponding alcohols[70-72]. GPX4 uniquely accommodates membrane phospholipids within its catalytic site, preventing the propagation of lipid peroxidation. Its enzymatic activity depends on GSH as electron donor, linking ferroptosis resistance to intracellular thiol redox homeostasis[73,74]. Because GPX4 contains a catalytically essential selenocysteine (Sec) residue, selenium availability and selenoprotein biosynthesis are indispensable for the suppression of ferroptosis[71]. When intracellular GSH levels decrease, GPX4 activity declines, allowing lipid peroxides to accumulate. Alternative thiol reductants such as β-mercaptoethanol can partially reduce GPX4, but they cannot fully substitute the functions of GSH[75].

Through these mechanisms, GPX4 establishes the redox threshold that separates cell survival from lipid peroxidation-induced death, functioning as the master regulator of ferroptosis.

2.3 System Xc-: cystine uptake and biosynthesis of GSH and polysulfides

The supply of cysteine, the rate-limiting precursor for GSH, is maintained by the cystine/glutamate antiporter system Xc-, composed of SLC7A11 (also known as xCT) and SLC3A2[76]. Inhibition of system Xc-, for example by erastin, depletes intracellular cysteine and GSH[64], thereby decreasing GPX4 activity and promoting ferroptosis. Conversely, system Xc- upregulation enhances cystine uptake and confers ferroptosis resistance, a mechanism frequently exploited by cancer cells to survive oxidative stress.

In addition to GSH, cysteine metabolism produces reactive sulfur species such as hydrogen polysulfides (H2Sn), which can act as nucleophilic and redox-active metabolites scavenging reactive oxygen species and lipid peroxyl radicals, thereby mitigating lipid peroxidation independently of the GPX4–GSH axis[77,78].

2.4 FSP1, CoQ10, and vitamin K: an alternative ferroptosis defense line

Although GPX4 is indispensable for detoxifying LOOH, ferroptosis can also be prevented by a parallel antioxidant system centered on ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1, formerly AIFM2)[79,80]. FSP1 is an NAD(P)H-dependent oxidoreductase that regenerates the lipophilic antioxidant ubiquinol (CoQH2) from coenzyme Q10 (ubiquinone) at cellular membranes[81,82]. CoQH2 traps lipid radicals and halts the propagation of lipid peroxidation independently of GPX4. Furthermore, FSP1 participates in the reduction of vitamin K to its hydroquinone form, linking the vitamin K redox cycle to ferroptosis defense[83]. Together, the GPX4–GSH and FSP1–CoQ10/vitamin K systems provide overlapping protection against oxidative lipid damage, ensuring cellular survival under diverse metabolic conditions.

2.5 ACSL4, MBOAT, and the lipid composition of membranes

Ferroptosis sensitivity is strongly influenced by the fatty acid composition of phospholipids. Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4) preferentially activates polyunsaturated fatty acids such as arachidonic and adrenic acids, forming acyl-CoA derivatives that are incorporated into phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) by membrane-bound O-acyltransferases (MBOATs)[84,85]. These PUFA-PE species are particularly vulnerable to peroxidation and act as key executioner lipids in ferroptosis. Cells lacking ACSL4 or MBOAT1/2 exhibit decreased levels of PUFA-phospholipids and display marked resistance to ferroptosis. Thus, ACSL4 and MBOAT enzymes define a lipid metabolic landscape that determines whether a cell is predisposed to ferroptotic cell death.

2.6 Therapeutic perspectives

Ferroptosis integrates multiple metabolic pathways: (1) iron catalysis driving hydroxyl radical formation, (2) lipid metabolism determining peroxidation substrates, (3) thiol metabolism maintaining the redox environment, and (4) selenium metabolism enabling selenoprotein-based detoxification. Disruption of any of these axes, including iron overload, PUFA enrichment, cysteine depletion, or selenium deficiency, can shift the cellular balance towards ferroptotic collapse. Therapeutically, manipulating these pathways offers both cytoprotective and cytotoxic opportunities. Of particular interest, the ability of ferroptosis to target (chemo)therapy-resistant and metastatic cancers underscores its potential as a highly attractive strategy for future treatments[86-89]. Ferroptosis inducers such as erastin or GPX4 inhibitors may selectively eliminate drug-resistant tumor cells, whereas inhibitors including liproxstatin-1, ferrostatin-1, vitamin E, and CoQ10 can protect neurons and cardiac tissues from oxidative damage[65]. Targeting ACSL4-dependent lipid remodeling or enhancing FSP1-mediated antioxidant defense provides additional strategies to modulate ferroptosis in disease contexts. Altogether, ferroptosis represents a metabolic checkpoint that determines cell fate by balancing iron-driven lipid oxidation with multi-layered redox and metabolic defense systems.

3. Redoxins in Ferroptosis

Redoxins and associated proteins, as well as those that interact with them, play a crucial role in regulating various aspects of ferroptosis, e.g., GSH metabolism, iron homeostasis, and post-translational modifications of ferroptotic proteins. Several of the described functions of redoxins are known for a long time but were not directly connected to ferroptosis. The impact of changed redoxin function on ferroptosis could also be based on secondary effects, e.g., the increase in superoxide formation upon loss of mitochondrial redoxins[90,91] or activation of the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) pathway[92,93], a major regulator of transcription of antioxidant and anti-ferroptotic enzymes[65]. This section mainly focuses on direct effects on ferroptotic pathways.

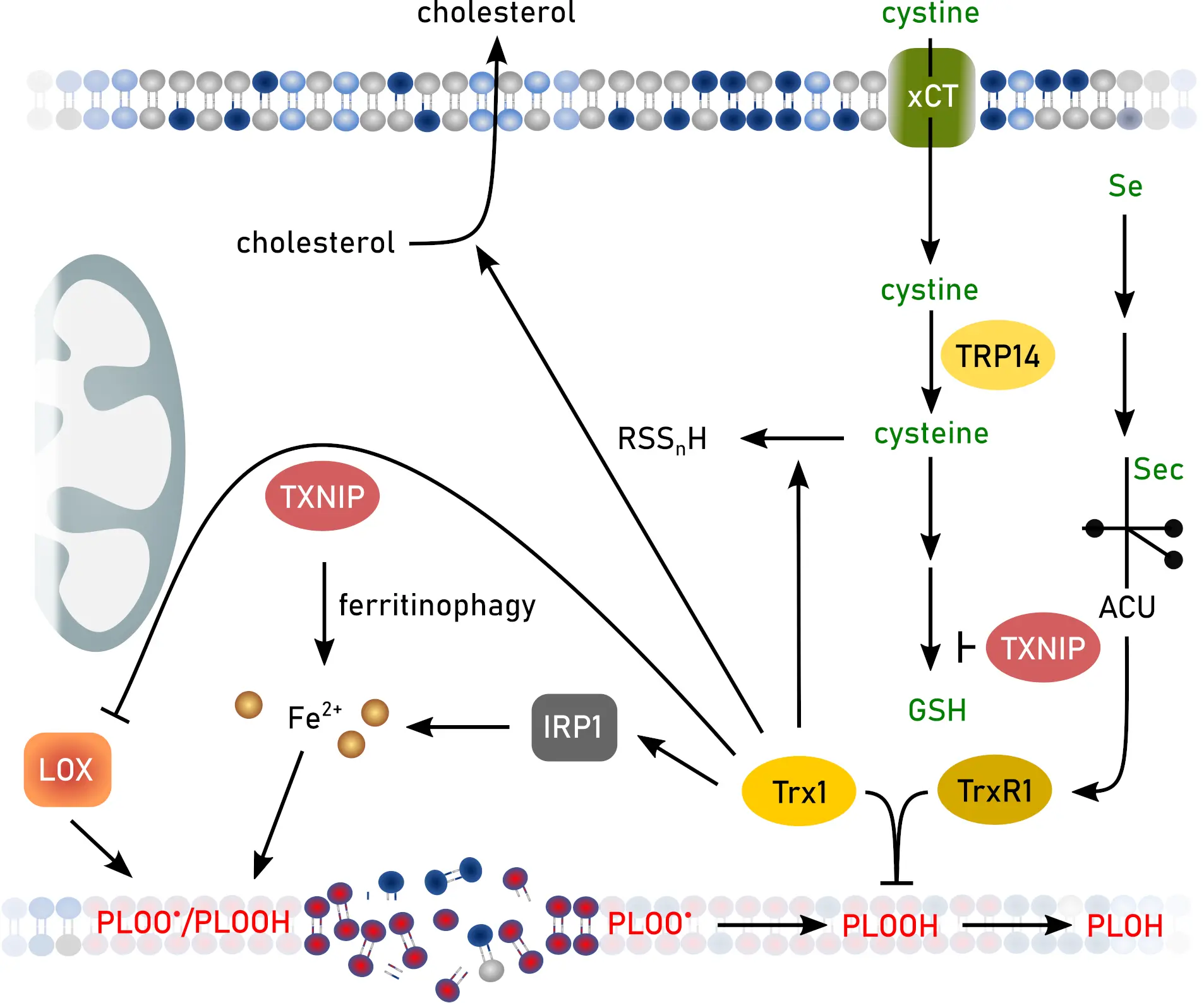

3.1 Trxs

The cytosolic Trx system might directly protect against ferroptosis by reducing lipid hydroperoxides (Figure 3). Hydroperoxides of beta-linoleoyl-gamma-palmitoylphosphatidylcholine formed after photoperoxidation of liposomes were decreased to 2/3 by addition of TrxR and to less than 50% after addition of TrxR and Trx[94]. This potential peroxide reducing function is increased in ferroptosis resistant non-small cell lung cancer lacking the tumor suppressor SMARCA4. Lack of SMARCA4 inhibits expression of the aldehyde dehydrogenase ALDH16A1 that binds to the Trx1 active site and inhibits its function but also promotes lysosomal degradation of the redoxin[95]. The newly developed ferroptosis inducing compound ferroptocide is a Trx inhibitor[96]. Ferroptocide binds covalently to the active site cysteines 32 and 35 and the additional cysteine 73 of Trx1[96] inhibiting its enzymatic function and the coordination of the FeS-cluster[13].

Figure 3. Functions of the Trx system and TXNIP or TRP14 in ferroptosis. Created in inkscape. Trx: thioredoxin; TXNIP: Trx-interacting protein; TRP14: thioredoxin-related protein of 14 kDa; GSH: glutathione; IRP: iron regulatory protein; LOX: lipid oxidase.

Moreover, selenide produced by the reduction of selenite by NADPH and TrxR is an efficient inhibitor of lipoxygenases[97]. Trx1 promotes reverse cholesterol transport (Figure 3) via nuclear translocation of liver X receptor α and subsequent increase of ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 expression, thereby inhibiting hepatic steatosis[98], a disease condition linked to ferroptosis[99]. In addition, cholesterol is thought to contribute to the lipid peroxidation burden during ferroptosis[100]. Trx is able to form hydrogen sulfide and polysulfides in vitro (Figure 3)[101]. This might have an anti-ferroptotic function since sulfane sulfur species can protect against lipid peroxidation[78].

Trxs are also involved in iron homeostasis via regulation of IRP1 activity, as shown above[13]. The role of TrxRs in ferroptosis is not clear. Although they are inhibited by GPX4 inhibitors such as RSL3 in vitro, treatment of cells with more specific TrxR inhibitors, e.g., TRi, does not induce ferroptosis[102] indicating that TrxR is not directly involved in ferroptosis. However, as mentioned above, TrxR is able to reduce lipid hydroperoxides[94,97]. Furthermore, TrxR inhibition by different gold-based compounds induces ferroptosis in KRAS-WT lung cancer[103], triple-negative breast cancer cells[104], and hepatic cells[105]. In contrast, TrxR1 knockout in pancreatic cancer cells increases protection against ferroptosis via upregulated levels of GPX4[106]. The authors of this study explain the upregulation with the increased availability of Sec, although this was not shown for knockout of other selenoproteins, e.g., GPX1[107].

The Trx-interacting protein (TXNIP) promotes ferroptosis in mouse models of bronchopulmonary dysplasia[108], cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury[109], sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy[110], and polycystic ovary syndrome[111]. Moreover, the role of TXNIP in ferroptosis is described as important in initiating sarcopenia[112], and as a prognostic/diagnostic marker in breast[113], gastric[114], bladder[115], and lung cancer[116,117], intervertebral disc degeneration[118], as well as multiple sclerosis[119]. Surprisingly, the role of TXNIP in liver ferroptosis seems to be the opposite. Decreased levels of TXNIP increase cholesterol content in liver[120] and initiate liver fibrosis via ferroptosis[121]. The impact of TXNIP on ferroptosis seems to be manifold, as it downregulates SLC7A11 and GPX4 levels[108,122], increases the labile iron pool via NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy[123,124], and disrupts GSH synthesis (Figure 3)[112].

Thioredoxin-related protein of 14 kDa (TRP14) may be the protein mainly responsible for the reduction of intracellular cystine (Figure 3)[125]. Thereby, TRP14 supports the function of SLC7A11 and the synthesis of GSH.

3.2 Grxs

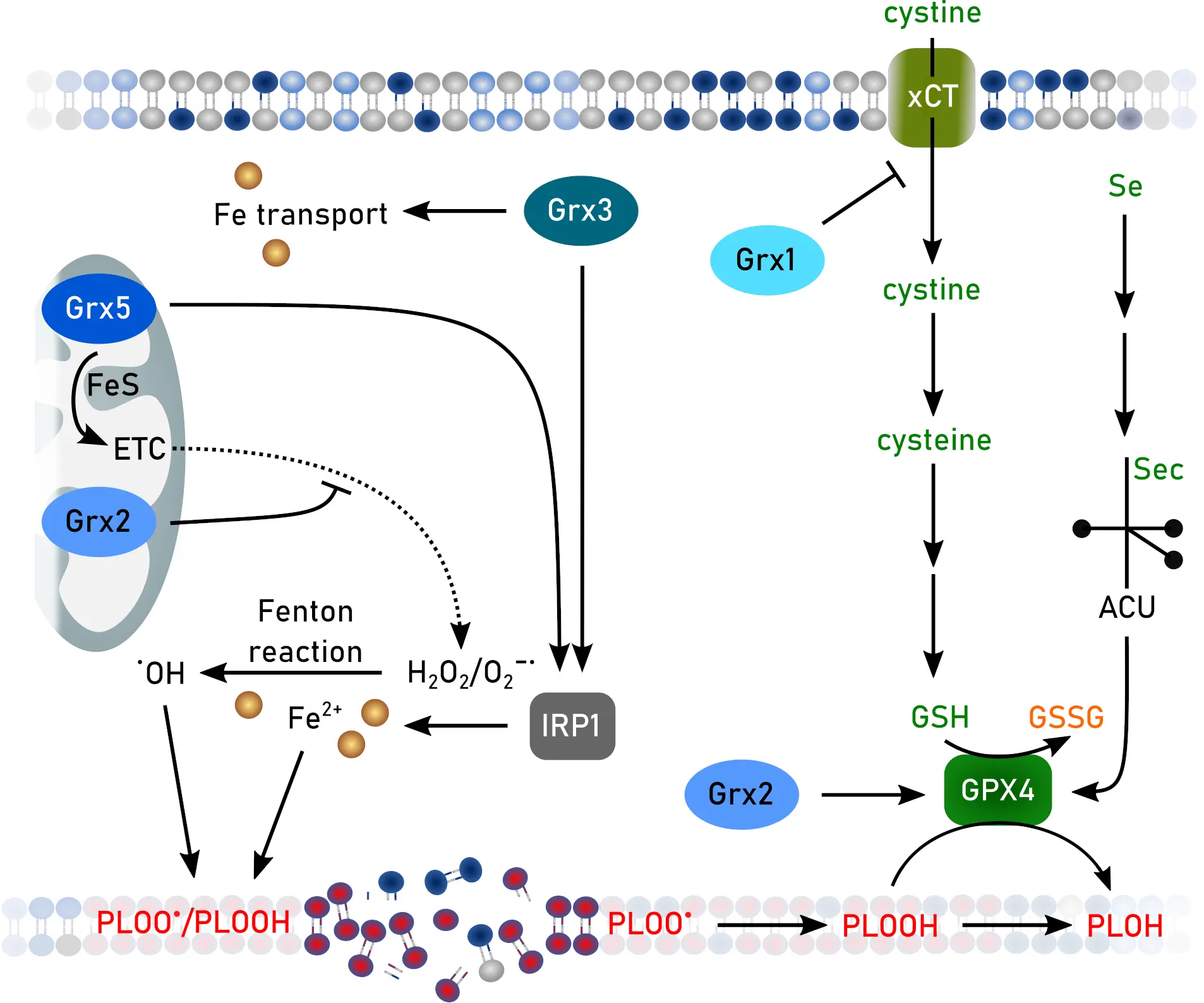

As described above, Grxs function either as oxidoreductases (class I Grxs 1 and 2) or FeS-cluster transferases/regulators of iron homeostasis (class II Grxs 3 and 5).

Both Grxs 1 and 2 are involved in protection against lens damage[126,127]. Ferrostatin-1 is able to increase survival of UV-B-treated human lens epithelial cells and decreases the opaque region in UV-B irradiated mouse lenses[128] linking lens damage to ferroptosis. Grx2 knockout or overexpression exacerbates or diminishes lipid peroxidation in human lens epithelial cells or opacity in mouse lenses, respectively, after treatment with ferroptosis inducers or UV-B via modulation of mitochondrial structure and the GSH/GSSG ratio[128].

S-glutathionylation is linked to ferroptosis-related proteins. Grx1 de-glutathionylates cysteine residues 23 and 240 of the ovarian tumor deubiquitinase OTUB1[129]. In concert with the E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme UBCH5a, glutathionylated OTUB1 interacts with SLC7A11 and prevents proteasomal degradation (Figure 4). Thereby, knockdown of Grx1 leads to increased levels of SLC7A11 and of GSH in lung cells[129]. Surprisingly, loss of Grx1 shows no effect on ferroptosis in MEFs or HeLa cells. In contrast, loss of Grx2 increases ferroptosis vulnerability. Grx2 is essential to de-glutathionylate GPX4, thereby affecting structural features important for lipid binding of GPX4[130]. These effects impair functionality of this anti-ferroptotic enzyme. Upon ferroptosis induction, Grx2 becomes activated by disassembly of the FeS-cluster introducing the FeS-cluster bound in Grx2 dimers as a ferroptosis sensor. In line, Grx2 knockout mice resemble phenotypes of mice expressing a hypomorphic Gpx4 allele, such as lipid peroxidation in the brain or loss of parvalbumin-positive neurons[71].

Figure 4. Functions of Grxs in ferroptosis. Created in inkscape. Grx: glutaredoxin; ETC: electron transport chain; GSH: glutathione, GSSG: GSH disulfide; IRP: iron regulatory protein.

Although currently not found to be directly linked to the activity of Grxs, ADP-ribosylation factor 6 is S-glutathionylated under ferroptotic conditions, regulating localization of the transferrin receptor on the cell membrane and transferrin uptake[131].

Disturbed FeS-cluster biosynthesis promotes ferroptosis in various cancer cell lines[132,133], whereas intact FeS-cluster biosynthesis inhibits ferroptosis[134]. Consistent with these findings, downregulation of Grx5 sensitizes cisplatin-resistant head and neck cancer towards ferroptosis[135]. Knockout of either Grx5 or Grx3 leads to iron accumulation in cells[31,136,137], impaired FeS cluster biosynthesis[138], and deregulated iron homeostasis via IRPs[31,137,139] (Figure 4).

Free fatty acids, that might also contribute to ferroptosis[100], deplete Grx5 in a model of type 2 diabetes mellitus[140]. In addition, Grx3 displays protein kinase C-θ activity. Although this specific protein kinase is currently not found to be involved in ferroptosis, protein kinase C-β is pro-ferroptotic via phosphorylation and thereby activation of ACSL4[141].

3.3 Prxs

Inhibition of Prx1 triggers ferroptosis in non-small cell lung cancer[142]. Conversely, overexpression of Prx1 prevents ferroptosis in a model of oxygen-glucose deprivation/reperfusion-induced neuronal cell death[143]. Lai et al.[144] claim that Prx1’s peroxidase activity in prostate cancer is preserved by the oncogene Holliday junction recognition protein (HJURP) that is found in several cancer types[145]. Formation of intermolecular disulfides between HJURP and Prx1 protects the active site of the redoxin against overoxidation during ferroptosis induction. Binding of Prx1 to long non-coding RNA LncFASA leads to phase separation, formation of Prx1-containing condensates, and subsequently ferroptotic cell death in triple-negative breast cancer[146]. Prxs 1 and 2 are targets for direct binding to artesunate, a derivative of the anti-malaria and anti-tumor drug artemisinin. Binding to Prx1 Gly4 or Prx2 Arg7 and Thr120 promotes ferroptosis in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma[147]. In addition, Prx1 protects diffuse large B-cell lymphoma against erastin-induced ferroptosis by inhibition of the MAPK/ERK pathway[148]. Song et al.[149] suggested that, next to the peroxidase activity, the chaperone activity of Prx1 also provides ferroptosis protection. Prx1 Cys83 binds to cullin-3, a ubiquitin ligase modulating Nrf2 ubiquitination[150], and thereby inhibits degradation of Nrf2 allowing transcription of anti-ferroptotic enzymes[149].

Lipid hydroperoxides are substrates for Prx2 (Figure 5)[51] suggesting an anti-ferroptotic function as demonstrated in adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells[151]. Prx2 interaction with different proteins regulates its exosomal secretion. Binding of apoptosis-linked gene-2-interacting protein X to its N-terminal region promotes secretion, whereas keratin 20 binding at this region inhibits secretion and thereby prevents ferroptosis in kidney tubular cells[152]. Oral squamous cell carcinoma cells protect themselves against ferroptosis by upregulation of RUNT-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2), a protein connected to survival and metastasis of various cancer types[153]. RUNX2 binds to the promoter of the Prx2 encoding gene and enhances the transcription, thereby decreasing vulnerability towards ferroptosis[154]. In contrast, binding of nuclear factor of activated T cells 5 to the promotor leads to downregulated Prx2 expression and increased ferroptosis in pancreatic β-cells during progression of obese type 2 diabetes mellitus[155].

Figure 5. Functions of Prxs in ferroptosis. Created in inkscape. Prx: peroxiredoxin; ACSL3: synthetase long-chain-fatty-acid family member 3; ACSL4: acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain-fatty-acid family member 4; α-TO: α-tocopherol/vitamin E; CoQ10: co-enzyme Q10; FSP: ferroptosis suppressor protein; GSH: glutathione; GSSG: GSH disulfide; GPX: GSG peroxidase; MBOAT: membrane-bound O-acetyltransferase; MUFA: mono-unsaturated fatty acid; NADPH: reduced nicotinamide adenin dinucleotide phosphate; NAD(P)+: oxidized nicotinamide adenin dinucleotide (phosphate), Nrf2: nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; PUFA: poly-unsaturated fatty acid.

Hyperoxidized (sulfinic and sulfonic acids) Prx3 was suggested as a ferroptosis marker[156]. Although less sensitive to hyperoxidation by H2O2 than Prxs 1 and 2, Prx3 is rapidly hyperoxidized by lipid hydroperoxides[157,158]. Under these conditions, Prx3 is localized not only in mitochondria, but also at the plasma membrane[53,156,159]. Since enzymes that are able to inhibit or reduce hyperoxidation of Prx3, sulfiredoxin[160], Grx2, and Trx2[161], are only partly correlated to ferroptosis[162], the specificity of hyperoxidized Prx3 as a ferroptotic marker needs further investigation. Downregulation of Prx3 was observed in patients suffering from osteoarthritis and knock-out of this redoxin induced ferroptosis and cartilage injury in an osteoarthritis mouse model[163]. Prx3 is connected to ferroptosis in ovarian cancer stem cells[164].

Prx4, together with all other Prxs, is upregulated in multiple myeloma patients and serves as a prognostic and diagnostic marker[165].

Prx5 protects against ferroptosis in bladder cancer, where it is also a potential biomarker[166], colorectal cancer cells[167], and cisplatin-induced ferroptosis leading to acute kidney injury[168].

The best investigated Prx in the context of ferroptosis is Prx6. Prx6 protects against ferroptosis in intestinal epithelial cells[169], heart failure[170], diabetic podocyte injury[171], lung endothelial cells[172,173], sepsis-associated acute lung injury[174], chronic obstructive pulmonary disease[175], periodontitis[176], xenograft tumor models[177], neuroblastoma[178], as well as colorectal cancer cells[179]. Mechanistically, this redoxin directly reduces lipid hydroperoxides[180,181], alleviates ferroptosis-induced mitophagy[182], remodels membrane phospholipid composition[183], or diminishes inflammatory pathways[173,176]. All Prx6 functions, including peroxidase, phospholipase, lysophosphatidylcholine acyl transferase, and selenium transfer and utilization factor, modulate ferroptosis (Figure 5)[58,59,184,185]. The selenium transfer function was discovered only recently. Prx6 operates through its function as a selenium acceptor protein, channeling reactive selenium species toward the biosynthesis of selenoproteins, especially GPX4. A direct interaction between Prx6 and GPX4 and the importance of Sec in GPX4 has been described before[71,96]. In intracellular selenium metabolism, selenium must be converted into Sec for selenoprotein translation. Canonically, this involves the decomposition of Sec by selenocysteine β-lyase, producing selenide that is phosphorylated by selenophosphate synthetase 2 (SEPHS2) to generate selenophosphate for Sec-tRNA synthesis[186]. Because selenide is highly reactive, it has long been hypothesized that specific molecular carriers exist to transport selenium in a stabilized form within cells[187]. Prx6 is now identified as such a selenium-acceptor protein, functioning as a safe and efficient mediator of intracellular selenium trafficking[60,177,178]. Prx6 directly binds selenide or selenol intermediates at its catalytic cysteine 47 in the presence of GSH. Through this covalent relay, Prx6 transfers selenium to SEPHS2 and thereby enhances the efficiency of Sec-tRNA[Ser]Sec formation and subsequent selenoprotein translation. In line, Prx6 knockout mice exhibit markedly reduced levels of GPX4 and other selenoproteins, with this decrease being particularly pronounced in the brain[177], highlighting the critical role of this redoxin in selenium metabolism and providing a missing link in selenoprotein biology that explains how cells coordinate thiol and selenium metabolism to counteract lipid peroxidation. Given the central role of GPX4 in suppressing lipid peroxidation, these findings further suggest that Prx6 may exert substantial influence on ferroptosis-related pathologies through its regulation of GPX4 expression. Importantly, recent studies indicate that deficiency in Prx6-dependent selenium delivery can significantly decrease GPX4 protein level, with a corresponding reduction in ferroptosis sensitivity of similar magnitude. However, the precise kinetics of selenium handover from Prx6 to SEPHS2, the structural determinants that govern selenium selectivity, and the extent to which Prx6 activity becomes rate-limiting during oxidative stress remain unclear. These unresolved questions underscore Prx6 as a potentially druggable regulatory node. Small molecules that stabilize the Prx6–selenium intermediate or enhance its interaction with SEPHS2 could augment GPX4 biosynthesis, whereas pharmacological inhibition of this pathway may sensitize cancer cells to ferroptosis-inducing therapies.

Prxs can undergo different posttranslational modifications that regulate the impact on ferroptosis. Membrane associated Prx1 can be phosphorylated at Tyr194 allowing the accumulation of H2O2[188] and lipid peroxidation. Inhibition of Tyr194 phosphorylation elevates the peroxidase activity of Prx1 and makes it an efficient anti-ferroptotic enzyme[143]. Lactylation of Prx1 at Lys67 enhances nuclear translocation and Nrf2-dependent transcription of anti-ferroptotic enzymes[189]. De-acetylation of Prx3 at Lys92 by the de-acetylase sirtuin 4 confers protection against ferroptosis in the context of liver ischemia-reperfusion injury[190].

In summary, redoxins are clearly involved in ferroptosis regulation, although many publications are rather descriptive, focusing only on survival in presence or absence of ferroptosis inhibitors/inducers and lipid peroxidation levels. The available data do not allow conclusions regarding the specific functions of the three distinct redoxin families in ferroptosis. Single enzymes affect different hallmarks of ferroptosis, e.g., Prx6 can provide GPX4 with selenium, directly reduce lipid hydroperoxides, or regulate the MUFA/PUFA ratio. Moreover, different cell types or metabolic conditions might contribute to the different importance of the redoxin families. GPX4 activity depends on GSH and selenium levels, which also affects either the Grx system (GSH-dependent activity of Grxs) or the Trx system (selenium-dependent activity of TrxR). Thus, context-dependent research focusing on molecular mechanisms is essential to validate the role of redoxins in ferroptosis.

4. Ferroptosis and Redoxins in Pathology

Several diseases are linked to both ferroptotic cell death and (mis-)function of redoxins. Redoxins contribute to diseases mainly in their roles as regulators of iron homeostasis and of redox signaling by modulating oxidative posttranslational modifications and/or levels of oxidants.

As evident from the above cited publications, cancer is such a disease with several examples showing the impact of redoxins or ferroptosis in cancer progression or therapy. Other examples of pathological conditions clearly linked to ferroptosis as well as redoxins include neurodegeneration[191-193], neuroinflammation and other inflammatory diseases[194,195], ischemia/reperfusion[196,197], diabetes mellitus[198,199], and iron-related diseases such as Friedreich’s Ataxia[200,201].

In most of these pathological conditions, the connection between ferroptosis and redoxins remains to be specified. As stated above, especially mechanistic insights are missing, and in the case of diseases, this is even more evident. Moreover, investigation of cell-type specificity may be important for addressing different diseases. Depending on the tumor, higher levels of Trx have been associated with both increased resistance and increased cell death[202]. Inhibition of the Trx system by auranofin induced cell death (most likely ferroptosis) only in non-endocrine small cell lung cancer, whereas inhibition of the Grx system by buthionine sulfoximine killed specifically the endocrine cells[203]. Ferroptosis susceptibility and impact on tumor growth differ between cancer types[204] and even within the same cancer type the protective ferroptotic pathway can change as shown for melanoma cells in which protection against ferroptosis shifts from GPX4 to FSP1 during lymphatic metastasis[205]. The recently demonstrated importance of FSP1 in a lung cancer mouse model[206], which was not observed in cell culture indicates further differences between in vivo and in vitro experiments, that should be also considered in evaluating the role of redoxins.

Based on the existing literature, modulation of redoxin’s activity offers new therapeutic strategies to induce or inhibit ferroptosis. Several redoxin inhibitors induce ferroptosis, such as the already mentioned Trx inhibitor ferroptocide. Moreover, arsenic trioxide, nitrosourea, e.g., busulfan or carmustine, or natural compounds, such as curcumine(-derivates) or piperlongumine, are potent inhibitors of the Trx and Grx systems via inhibition of TrxR, GR, or depletion of GSH[207,208] and inducers of ferroptosis[208-211]. At the same time, these compounds are promising or already approved anticancer drugs[208,210,212-214]. Inhibition of the Trx system should also inhibit Prxs. Nevertheless, some specific Prx inhibitors induce ferroptosis and exhibit anti-cancer activity, e.g., artesunate[147]. Finally, at least one compound, glaucocalyxin A, inhibits both TR1 and Prx1 to induce ferroptosis in cancer cells[142]. Future research will show whether all redoxin inhibitors, including the recently described very specific Prx3[215] or yet-to-be-developed specific Grx inhibitors, induce ferroptosis. To our knowledge, activators of redoxins have yet not been identified. Trx1’s activity is inhibited by binding to TXNIP and subsequent blocking of the active site[216]. Therefore, inhibition of TXNIP should increase Trx1 activity. Recently, such a TXNIP inhibitor, TIX100, has been published[217]. This compound is being tested in clinical trials targeting type 1 diabetes, but whether it inhibits ferroptosis remains unknown[218]. Nevertheless, activation of redoxin activity would be a novel strategy to suppress ferroptosis and combat diseases such as diabetes and neurodegeneration.

5. Conclusions

As modulators of redox and iron homeostasis, redoxins regulate hallmarks of ferroptosis. In fact, several hallmarks of ferroptosis were connected to the functions of thio-, gluta-, and peroxiredoxins years or even decades ago. However, compared to the number of publications related to ferroptosis, publications connecting ferroptosis and redoxins are surprisingly rare. Moreover, a number of these publications do not provide detailed mechanisms linking redoxin activities to ferroptotic pathways. Therefore, most data are rather descriptive based on knockout, inhibition, or overexpression of redoxins and subsequent measurement of lipid peroxidation and/or rescue by ferroptosis inhibitors/inducers. Future research addressing these knowledge gaps and linking redoxin activity to ferroptotic cell death should increase our knowledge in molecular mechanisms underlying or regulating ferroptosis in different (patho-)physiological conditions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all researchers that provided to the topic in other organisms and all authors that were not cited.

Authors contribution

Berndt C: Conceptualization, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing, visualization.

Ito J, Lillig CH: Writing-original draft, writing-review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

Carsten Berndt is an Editorial Board Member of Ferroptosis and Oxidative Stress. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

The research of the authors in aspects of redoxin functions related to ferroptosis was/is supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) (Christopher Horst Lillig: LI984/3-1/-2, LI984/4-1, GRK1947-A01; Carsten Berndt: BE3259/5-1/-2, BE3259/6-1, 417677437/GRK2578), the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI 22KK0253 and 25K01963 to Junya Ito), and the Research Commission of the Medical Faculty, Heinrich-Heine-University (2021-47 to Carsten Berndt).

Copyright

© The authors 2025.

References

-

1. Lillig CH, Holmgren A. Thioredoxin and related molecules–from biology to health and disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9(1):25-47.[DOI]

-

2. Hanschmann EM, Godoy JR, Berndt C, Hudemann C, Lillig CH. Thioredoxins, glutaredoxins, and peroxiredoxins–molecular mechanisms and health significance: From cofactors to antioxidants to redox signaling. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;19(13):1539-1605.[DOI]

-

3. Martin JL. Thioredoxin–a fold for all reasons. Structure. 1995;3(3):245-250.[DOI]

-

4. Laurent TC, Moore EC, Reichard P. Enzymatic synthesis of deoxyribonucleotides. IV. J Biol Chem. 1964;239:3436-3444.[DOI]

-

5. Holmgren A, Lu J. Thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase: Current research with special reference to human disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;396(1):120-124.[DOI]

-

6. Hirota K, Murata M, Sachi Y, Nakamura H, Takeuchi J, Mori K, et al. Distinct roles of thioredoxin in the cytoplasm and in the nucleus. A two-step mechanism of redox regulation of transcription factor NF-kappaB. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(39):27891-27897.[DOI]

-

7. Rubartelli A, Bajetto A, Allavena G, Wollman E, Sitia R. Secretion of thioredoxin by normal and neoplastic cells through a leaderless secretory pathway. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(34):24161-24164.[DOI]

-

8. Miranda-Vizuete A, Damdimopoulos AE, Spyrou G. The mitochondrial thioredoxin system. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2000;2(4):801-810.[DOI]

-

9. Sun QA, Kirnarsky L, Sherman S, Gladyshev VN. Selenoprotein oxidoreductase with specificity for thioredoxin and glutathione systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001;98(7):3673-3678.[DOI]

-

10. Spyrou G, Enmark E, Miranda-Vizuete A, Gustafsson J. Cloning and expression of a novel mammalian thioredoxin. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(5):2936-2941.[DOI]

-

11. Haendeler J, Hoffmann J, Tischler V, Berk BC, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Redox regulatory and anti-apoptotic functions of thioredoxin depend on S-nitrosylation at cysteine 69. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4(10):743-749.[DOI]

-

12. Casagrande S, Bonetto V, Fratelli M, Gianazza E, Eberini I, Massignan T, et al. Glutathionylation of human thioredoxin: A possible crosstalk between the glutathione and thioredoxin systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2002;99(15):9745-9749.[DOI]

-

13. Berndt C, Hanschmann EM, Jordt LM, Gellert M, Thewes L, Salas CO, et al. FeS-cluster coordination of vertebrate thioredoxin regulates suppression of hypoxia-induced factor 2α through iron regulatory protein 1. BioRxiv 235721 [Preprint]. 2020.[DOI]

-

14. Muckenthaler MU, Galy B, Hentze MW. Systemic iron homeostasis and the iron-responsive element/iron-regulatory protein (IRE/IRP) regulatory network. Annu Rev Nutr. 2008;28:197-213.[DOI]

-

15. Anderson CP, Shen M, Eisenstein RS, Leibold EA. Mammalian iron metabolism and its control by iron regulatory proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1823(9):1468-1483.[DOI]

-

16. Oliveira L, Bouton C, Drapier JC. Thioredoxin activation of iron regulatory proteins. Redox regulation of RNA binding after exposure to nitric oxide. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(1):516-521.[DOI]

-

17. Holmgren A. Glutathione-dependent synthesis of deoxyribonucleotides. Purification and characterization of glutaredoxin from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1979;254(9):3664-3671.[DOI]

-

18. Holmgren A. Glutathione-dependent synthesis of deoxyribonucleotides. Characterization of the enzymatic mechanism of Escherichia coli glutaredoxin. J Biol Chem. 1979;254(9):3672-3678.[DOI]

-

19. Gravina SA, Mieyal JJ. Thioltransferase is a specific glutathionyl mixed disulfide oxidoreductase. Biochemistry. 1993;32(13):3368-3376.[DOI]

-

20. Lillig CH, Berndt C, Holmgren A. Glutaredoxin systems. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1780(11):1304-1317.[DOI]

-

21. Berndt C, Hudemann C, Hanschmann EM, Axelsson R, Holmgren A, Lillig CH. How does iron-sulfur cluster coordination regulate the activity of human glutaredoxin 2? Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9(1):151-157.[DOI]

-

22. Johansson C, Kavanagh KL, Gileadi O, Oppermann U. Reversible sequestration of active site cysteines in a 2Fe-2S-bridged dimer provides a mechanism for glutaredoxin 2 regulation in human mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(5):3077-3082.[DOI]

-

23. Luthman M, Holmgren A. Glutaredoxin from calf thymus. Purification to homogeneity. J Biol Chem. 1982;257(12):6686-6690.[DOI]

-

24. Lundberg M, Fernandes AP, Kumar S, Holmgren A. Cellular and plasma levels of human glutaredoxin 1 and 2 detected by sensitive ELISA systems. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;319(3):801-809.[DOI]

-

25. Lundberg M, Johansson C, Chandra J, Enoksson M, Jacobsson G, Ljung J, et al. Cloning and expression of a novel human glutaredoxin (Grx2) with mitochondrial and nuclear isoforms. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(28):26269-26275.[DOI]

-

26. Lönn ME, Hudemann C, Berndt C, Cherkasov V, Capani F, Holmgren A, et al. Expression pattern of human glutaredoxin 2 isoforms: Identification and characterization of two testis/cancer cell-specific isoforms. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10(3):547-557.[DOI]

-

27. Wilms C, Lepka K, Häberlein F, Edwards S, Felsberg J, Pudelko L, et al. Glutaredoxin 2 promotes SP-1-dependent CSPG4 transcription and migration of wound healing NG2 glia and glioma cells: Enzymatic Taoism. Redox Biol. 2022;49:102221.[DOI]

-

28. Johansson C, Lillig CH, Holmgren A. Human mitochondrial glutaredoxin reduces S-glutathionylated proteins with high affinity accepting electrons from either glutathione or thioredoxin reductase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(9):7537-7543.[DOI]

-

29. Lillig CH, Berndt C, Vergnolle O, Lönn ME, Hudemann C, Bill E, et al. Characterization of human glutaredoxin 2 as iron-sulfur protein: A possible role as redox sensor. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102(23):8168-8173.[DOI]

-

30. Jeong D, Cha H, Kim E, Kang M, Yang DK, Kim JM, et al. PICOT inhibits cardiac hypertrophy and enhances ventricular function and cardiomyocyte contractility. Circ Res. 2006;99(3):307-314.[DOI]

-

31. Haunhorst P, Hanschmann EM, Bräutigam L, Stehling O, Hoffmann B, Mühlenhoff U, et al. Crucial function of vertebrate glutaredoxin 3 (PICOT) in iron homeostasis and hemoglobin maturation. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24(12):1895-1903.[DOI]

-

32. Rodríguez-Manzaneque MT, Tamarit J, Bellí G, Ros J, Herrero E. Grx5 is a mitochondrial glutaredoxin required for the activity of iron/sulfur enzymes. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13(4):1109-1121.[DOI]

-

33. Wingert RA, Galloway JL, Barut B, Foott H, Fraenkel P, Axe JL, et al. Deficiency of glutaredoxin 5 reveals Fe-S clusters are required for vertebrate haem synthesis. Nature. 2005;436(7053):1035-1039.[DOI]

-

34. Lillig CH, Berndt C. Glutaredoxins in thiol/disulfide exchange. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18(13):1654-1665.[DOI]

-

35. Begas P, Liedgens L, Moseler A, Meyer AJ, Deponte M. Glutaredoxin catalysis requires two distinct glutathione interaction sites. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14835.[DOI]

-

36. Zahedi Avval F, Holmgren A. Molecular mechanisms of thioredoxin and glutaredoxin as hydrogen donors for Mammalian s phase ribonucleotide reductase. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(13):8233-8240.[DOI]

-

37. Geissel F, Lang L, Husemann B, Morgan B, Deponte M. Deciphering the mechanism of glutaredoxin-catalyzed roGFP2 redox sensing reveals a ternary complex with glutathione for protein disulfide reduction. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):1733.[DOI]

-

38. Daniel T, Faruq HM, Jordt LM, Manuela G, Lillig CH. Role of GSH and iron-sulfur glutaredoxins in iron metabolism—review. Molecules. 2020;25(17):3860.[DOI]

-

39. Berndt C, Christ L, Rouhier N, Mühlenhoff U. Glutaredoxins with iron-sulphur clusters in eukaryotes-Structure, function and impact on disease. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 2021;1862(1):148317.[DOI]

-

40. Johansson C, Roos AK, Montano SJ, Sengupta R, Filippakopoulos P, Guo K, et al. The crystal structure of human GLRX5: Iron-sulfur cluster co-ordination, tetrameric assembly and monomer activity. Biochem J. 2011;433(2):303-311.[DOI]

-

41. Berndt C, Lillig CH. Glutathione, glutaredoxins, and iron. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2017;27(15):1235-1251.[DOI]

-

42. Liedgens L, Zimmermann J, Wäschenbach L, Geissel F, Laporte H, Gohlke H, et al. Quantitative assessment of the determinant structural differences between redox-active and inactive glutaredoxins. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):1725.[DOI]

-

43. Trnka D, Engelke AD, Gellert M, Moseler A, Hossain MF, Lindenberg TT, et al. Molecular basis for the distinct functions of redox-active and FeS-transfering glutaredoxins. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):3445.[DOI]

-

44. Wood ZA, Schröder E, Robin Harris J, Poole LB. Structure, mechanism and regulation of peroxiredoxins. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28(1):32-40.[DOI]

-

45. Jang HH, Lee KO, Chi YH, Jung BG, Park SK, Park JH, et al. Two enzymes in one; two yeast peroxiredoxins display oxidative stress-dependent switching from a peroxidase to a molecular chaperone function. Cell. 2004;117(5):625-635.[DOI]

-

46. Stöcker S, Maurer M, Ruppert T, Dick TP. A role for 2-Cys peroxiredoxins in facilitating cytosolic protein thiol oxidation. Nat Chem Biol. 2018;14(2):148-155.[DOI]

-

47. Stöcker S, Van Laer K, Mijuskovic A, Dick TP. The conundrum of hydrogen peroxide signaling and the emerging role of peroxiredoxins as redox relay hubs. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2018;28(7):558-573.[DOI]

-

48. Rhee SG, Kil IS. Multiple functions and regulation of mammalian peroxiredoxins. Annu Rev Biochem. 2017;86:749-775.[DOI]

-

49. Hall A, Nelson K, Poole LB, Karplus PA. Structure-based insights into the catalytic power and conformational dexterity of peroxiredoxins. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15(3):795-815.[DOI]

-

50. Immenschuh S, Baumgart-Vogt E, Tan M, Iwahara S, Ramadori G, Fahimi HD. Differential cellular and subcellular localization of heme-binding protein 23/peroxiredoxin I and heme oxygenase-1 in rat liver. J Histochem Cytochem. 2003;51(12):1621-1631.[DOI]

-

51. Cha MK, Yun CH, Kim IH. Interaction of human thiol-specific antioxidant protein 1 with erythrocyte plasma membrane. Biochemistry. 2000;39(23):6944-6950.[DOI]

-

52. Cao Z, Lindsay JG, Isaacs NW. Mitochondrial peroxiredoxins. Subcell Biochem. 2007;44:295-315.[DOI]

-

53. Whitaker HC, Patel D, Howat WJ, Warren AY, Kay JD, Sangan T, et al. Peroxiredoxin-3 is overexpressed in prostate cancer and promotes cancer cell survival by protecting cells from oxidative stress. Br J Cancer. 2013;109(4):983-993.[DOI]

-

54. Thapa P, Ding N, Hao Y, Alshahrani A, Jiang H, Wei Q. Essential roles of peroxiredoxin IV in inflammation and cancer. Molecules. 2022;27(19):6513.[DOI]

-

55. Manevich Y, Feinstein SI, Fisher AB. Activation of the antioxidant enzyme 1-CYS peroxiredoxin requires glutathionylation mediated by heterodimerization with pi GST. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2004;101(11):3780-3785.[DOI]

-

56. Trujillo M, Ferrer-Sueta G, Thomson L, Flohé L, Radi R. Kinetics of peroxiredoxins and their role in the decomposition of peroxynitrite. Subcell Biochem. 2007;44:83-113.[DOI]

-

57. Knoops B, Goemaere J, Van der Eecken V, Declercq JP. Peroxiredoxin 5: Structure, mechanism, and function of the mammalian atypical 2-Cys peroxiredoxin. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15(3):817-829.[DOI]

-

58. Chen JW, Dodia C, Feinstein SI, Jain MK, Fisher AB. 1-Cys peroxiredoxin, a bifunctional enzyme with glutathione peroxidase and phospholipase A2 activities. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(37):28421-28427.[DOI]

-

59. Fisher AB, Dodia C, Sorokina EM, Li H, Zhou S, Raabe T, et al. A novel lysophosphatidylcholine acyl transferase activity is expressed by peroxiredoxin 6. J Lipid Res. 2016;57(4):587-596.[DOI]

-

60. Fujita H, Tanaka YK, Ogata S, Suzuki N, Kuno S, Barayeu U, et al. PRDX6 augments selenium utilization to limit iron toxicity and ferroptosis. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2024;31(8):1277-1285.[DOI]

-

61. Rhee SG, Kang SW, Chang TS, Jeong W, Kim K. Peroxiredoxin, a novel family of peroxidases. IUBMB Life. 2001;52(1-2):35-41.[DOI]

-

62. Jönsson TJ, Murray MS, Johnson LC, Lowther WT. Reduction of cysteine sulfinic acid in peroxiredoxin by sulfiredoxin proceeds directly through a sulfinic phosphoryl ester intermediate. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(35):23846-23851.[DOI]

-

63. Biteau B, Labarre J, Toledano MB. ATP-dependent reduction of cysteine–sulphinic acid by S. cerevisiae sulphiredoxin. Nature. 2003;425(6961):980-984.[DOI]

-

64. Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, et al. Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell. 2012;149(5):1060-1072.[DOI]

-

65. Berndt C, Alborzinia H, Amen VS, Ayton S, Barayeu U, Bartelt A, et al. Ferroptosis in health and disease. Redox Biol. 2024;75:103211.[DOI]

-

66. Dixon SJ, Olzmann JA. The cell biology of ferroptosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2024;25(6):424-442.[DOI]

-

67. Mishima E, Conrad M. Nutritional and metabolic control of ferroptosis. Annu Rev Nutr. 2022;42:275-309.[DOI]

-

68. Hirata Y, Mishima E. Membrane dynamics and cation handling in ferroptosis. Physiology. 2024;39(2):73-87.[DOI]

-

69. Conrad M, Pratt DA. The chemical basis of ferroptosis. Nat Chem Biol. 2019;15(12):1137-1147.[DOI]

-

70. Maiorino M, Gregolin C, Ursini F. Phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase. Methods Enzymol. 1990;186:448-457.[DOI]

-

71. Ingold I, Berndt C, Schmitt S, Doll S, Poschmann G, Buday K, et al. Selenium utilization by GPX4 is required to prevent hydroperoxide-induced ferroptosis. Cell. 2018;172(3):409-422.[DOI]

-

72. Nakamura T, Ito J, Mourão ASD, Wahida A, Nakagawa K, Mishima E, et al. A tangible method to assess native ferroptosis suppressor activity. Cell Rep Methods. 2024;4(3):100710.[DOI]

-

73. Friedmann Angeli JP, Schneider M, Proneth B, Tyurina YY, Tyurin VA, Hammond VJ, et al. Inactivation of the ferroptosis regulator Gpx4 triggers acute renal failure in mice. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16(12):1180-1191.[DOI]

-

74. Yang WS, SriRamaratnam R, Welsch ME, Shimada K, Skouta R, Viswanathan VS, et al. Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by GPX4. Cell. 2014;156(1-2):317-331.[DOI]

-

75. Zheng J, Zhang W, Ito J, Henkelmann B, Xu C, Mishima E, et al. N-acetyl-L-cysteine averts ferroptosis by fostering glutathione peroxidase 4. Cell Chem Biol. 2025;32(5):767-775.[DOI]

-

76. Sato H, Tamba M, Kuriyama-Matsumura K, Okuno S, Bannai S. Molecular cloning and expression of human xCT, the light chain of amino acid transport system xc-. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2000;2(4):665-671.[DOI]

-

77. Ogata S, Matsunaga T, Jung M, Barayeu U, Morita M, Akaike T. Persulfide biosynthesis conserved evolutionarily in all organisms. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2023;39(13-15):983-999.[DOI]

-

78. Barayeu U, Schilling D, Eid M, Xavier da Silva TN, Schlicker L, Mitreska N, et al. Hydropersulfides inhibit lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis by scavenging radicals. Nat Chem Biol. 2023;19(1):28-37.[DOI]

-

79. Doll S, Freitas FP, Shah R, Aldrovandi M, da Silva MC, Ingold I, et al. FSP1 is a glutathione-independent ferroptosis suppressor. Nature. 2019;575(7784):693-698.[DOI]

-

80. Bersuker K, Hendricks JM, Li Z, Magtanong L, Ford B, Tang PH, et al. The CoQ oxidoreductase FSP1 acts parallel to GPX4 to inhibit ferroptosis. Nature. 2019;575(7784):688-692.[DOI]

-

81. Nakamura T, Mishima E, Yamada N, Mourão ASD, Trümbach D, Doll S, et al. Integrated chemical and genetic screens unveil FSP1 mechanisms of ferroptosis regulation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2023;30(11):1806-1815.[DOI]

-

82. Nakamura T, Hipp C, Santos Dias Mourão A, Borggräfe J, Aldrovandi M, Henkelmann B, et al. Phase separation of FSP1 promotes ferroptosis. Nature. 2023;619(7969):371-377.[DOI]

-

83. Mishima E, Ito J, Wu Z, Nakamura T, Wahida A, Doll S, et al. A non-canonical vitamin K cycle is a potent ferroptosis suppressor. Nature. 2022;608(7924):778-783.[DOI]

-

84. Doll S, Proneth B, Tyurina YY, Panzilius E, Kobayashi S, Ingold I, et al. ACSL4 dictates ferroptosis sensitivity by shaping cellular lipid composition. Nat Chem Biol. 2017;13(1):91-98.[DOI]

-

85. Kagan VE, Mao G, Qu F, Angeli JP, Doll S, Croix CS, et al. Oxidized arachidonic and adrenic PEs navigate cells to ferroptosis. Nat Chem Biol. 2017;13(1):81-90.[DOI]

-

86. Viswanathan VS, Ryan MJ, Dhruv HD, Gill S, Eichhoff OM, Seashore-Ludlow B, et al. Dependency of a therapy-resistant state of cancer cells on a lipid peroxidase pathway. Nature. 2017;547(7664):453-457.[DOI]

-

87. Wang W, Green M, Choi JE, Gijón M, Kennedy PD, Johnson JK, et al. CD8+ T cells regulate tumour ferroptosis during cancer immunotherapy. Nature. 2019;569(7755):270-274.[DOI]

-

88. Rodriguez R, Schreiber SL, Conrad M. Persister cancer cells: Iron addiction and vulnerability to ferroptosis. Mol Cell. 2022;82(4):728-740.[DOI]

-

89. Nakamura T, Conrad M. Exploiting ferroptosis vulnerabilities in cancer. Nat Cell Biol. 2024;26(9):1407-1419.[DOI]

-

90. Scalcon V, Folda A, Lupo MG, Tonolo F, Pei N, Battisti I, et al. Mitochondrial depletion of glutaredoxin 2 induces metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease in mice. Redox Biol. 2022;51:102277.[DOI]

-

91. Holzerova E, Danhauser K, Haack TB, Kremer LS, Melcher M, Ingold I, et al. Human thioredoxin 2 deficiency impairs mitochondrial redox homeostasis and causes early-onset neurodegeneration. Brain. 2016;139(2):346-354.[DOI]

-

92. Patterson AD, Carlson BA, Li F, Bonzo JA, Yoo MH, Krausz KW, et al. Disruption of thioredoxin reductase 1 protects mice from acute acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity through enhanced NRF2 activity. Chem Res Toxicol. 2013;26(7):1088-1096.[DOI]

-

93. Dunigan K, Li Q, Li R, Locy ML, Wall S, Tipple TE. The thioredoxin reductase inhibitor auranofin induces heme oxygenase-1 in lung epithelial cells via Nrf2-dependent mechanisms. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2018;315(4):L545-L552.[DOI]

-

94. May JM, Morrow JD, Burk RF. Thioredoxin reductase reduces lipid hydroperoxides and spares alpha-tocopherol. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;292(1):45-49.[DOI]

-

95. Bi G, Liang J, Bian Y, Shan G, Ren S, Shi H, et al. Targeting ALDH16A1 mediated thioredoxin lysosomal degradation to enhance ferroptosis susceptibility in SMARCA4-deficient NSCLC. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):8181.[DOI]

-

96. Llabani E, Hicklin RW, Lee HY, Motika SE, Crawford LA, Weerapana E, et al. Diverse compounds from pleuromutilin lead to a thioredoxin inhibitor and inducer of ferroptosis. Nat Chem. 2019;11(6):521-532.[DOI]

-

97. Björnstedt M, Odlander B, Kuprin S, Claesson HE, Holmgren A. Selenite incubated with NADPH and mammalian thioredoxin reductase yields selenide, which inhibits lipoxygenase and changes the electron spin resonance spectrum of the active site iron. Biochemistry. 1996;35(26):8511-8516.[DOI]

-

98. Wang X, Zhao H, Yan W, Liu Y, Yin T, Wang S, et al. Thioredoxin-1 promotes macrophage reverse cholesterol transport and protects liver from steatosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;516(4):1103-1109.[DOI]

-

99. You Y, Liu C, Liu T, Tian M, Wu N, Yu Z, et al. FNDC3B protects steatosis and ferroptosis via the AMPK pathway in alcoholic fatty liver disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2022;193(2):808-819.[DOI]

-

100. Noguchi N, Saito Y, Niki E. Lipid peroxidation, ferroptosis, and antioxidants. Free Radic Biol Med. 2025;237:228-238.[DOI]

-

101. Nagahara N, Koike S, Nirasawa T, Kimura H, Ogasawara Y. Alternative pathway of H2S and polysulfides production from sulfurated catalytic-cysteine of reaction intermediates of 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;496(2):648-653.[DOI]

-

102. Cheff DM, Huang C, Scholzen KC, Gencheva R, Ronzetti MH, Cheng Q, et al. The ferroptosis inducing compounds RSL3 and ML162 are not direct inhibitors of GPX4 but of TXNRD1. Redox Biol. 2023;62:102703.[DOI]

-

103. Andreani C, Bartolacci C, Melegari M, Sargentoni N, Luciani L, Marucci A, et al. Thioredoxin Reductase 1 inhibition triggers ferroptosis in KRAS-independent lung cancers. BioRxiv [Preprint]. 2025.[DOI]

-

104. Chepikova OE, Malin D, Strekalova E, Lukasheva EV, Zamyatnin AA Jr, Cryns VL. Lysine oxidase exposes a dependency on the thioredoxin antioxidant pathway in triple-negative breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020;183(3):549-564.[DOI]

-

105. Yang L, Wang H, Yang X, Wu Q, An P, Jin X, et al. Auranofin mitigates systemic iron overload and induces ferroptosis via distinct mechanisms. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5(1):138.[DOI]

-

106. Cai LL, Ruberto RA, Ryan MJ, Eaton JK, Schreiber SL, Viswanathan VS. Modulation of ferroptosis sensitivity by TXNRD1 in pancreatic cancer cells. BioRxiv [Preprint]. 2020.[DOI]

-

107. Cheng WH, Ho YS, Ross DA, Han Y, Combs GF, Jr. , Lei XG. Overexpression of cellular glutathione peroxidase does not affect expression of plasma glutathione peroxidase or phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase in mice offered diets adequate or deficient in selenium. J Nutr. 1997;127(5):675-680.[DOI]

-

108. Chen D, Yin F, Yang P, Xia W, Huang Y, Feng Y, et al. TXNIP mediates ferroptosis in a bronchopulmonary dysplasia mouse model by regulating the SLC7A11/GPX4 pathway. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):35188.[DOI]

-

109. Yang C, Meng X, Xia C, Sun Y, Ren Y, Wang J, et al. IGFBP2 plays a key role in aerobic exercise-mediated inhibition of ferroptosis in cardiac ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury. J Transl Med. 2025;23(1):1080.[DOI]

-

110. Chen Y, Feng X, Li Z, Wang X, Xiong W, Liu J, et al. Targeting ATF4-DDIT4/TXNIP induced mitochondrial dysfunction and ferroptosis: ISRIB as novel therapy for septic cardiomyopathy. J Transl Med. 2025;23(1):938.[DOI]

-

111. Zhang X, Liu J, Bai C, Fan Y, Song H, Huang Z, et al. Palmitic acid enhances the sensitivity of ferroptosis via endoplasmic reticulum stress mediated the ATF4/TXNIP axis in polycystic ovary syndrome. Phytomedicine. 2025;142:156777.[DOI]

-

112. Maimaiti Y, Abulitifu M, Ajimu Z, Su T, Zhang Z, Yu Z, et al. FOXO regulation of TXNIP induces ferroptosis in satellite cells by inhibiting glutathione metabolism, promoting Sarcopenia. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2025;82(1):81.[DOI]

-

113. Liang S, Bai YM, Zhou B. Identification of key ferroptosis genes and mechanisms associated with breast cancer using bioinformatics, machine learning, and experimental validation. Aging (Albany NY). 2024;16(2):1781-1795.[DOI]

-

114. Jin W, Liu J, Yang J, Feng Z, Feng Z, Huang N, et al. Identification of a key ceRNA network associated with ferroptosis in gastric cancer. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):20088.[DOI]

-

115. Yi K, Liu J, Rong Y, Wang C, Tang X, Zhang X, et al. Biological functions and prognostic value of ferroptosis-related genes in bladder cancer. Front Mol Biosci. 2021;8:631152.[DOI]

-

116. Zheng Y, Yang W, Wu W, Jin F, Lu D, Gao J, et al. Diagnostic and predictive significance of the ferroptosis-related gene TXNIP in lung adenocarcinoma stem cells based on multi-omics. Transl Oncol. 2024;45:101926.[DOI]

-

117. Li S, Qiu G, Wu J, Ying J, Deng H, Xie X, et al. Identification and validation of a ferroptosis-related prognostic risk-scoring model and key genes in small cell lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2022;11(7):1380-1393.[DOI]

-

118. Guo J, Yang Y, Niu J, Luo Z, Shi Q, Yang H. Establishment of ferroptosis-related key gene signature and its validation in compression-induced intervertebral disc degeneration rats. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2023.[DOI]

-

119. Song X, Wang Z, Tian Z, Wu M, Zhou Y, Zhang J. Identification of key ferroptosis-related genes in the peripheral blood of patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis and its diagnostic value. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(7):6399.[DOI]

-

120. Donnelly KL, Margosian MR, Sheth SS, Lusis AJ, Parks EJ. Increased lipogenesis and fatty acid reesterification contribute to hepatic triacylglycerol stores in hyperlipidemic Txnip-/- mice. J Nutr. 2004;134(6):1475-1480.[DOI]

-

121. Liao X, Liu L, Du J, Fan H, Yu Y, Luo Y, et al. METTL3 inhibits liver fibrosis via RBX1 stability and TXNIP-mediated ferroptosis. Hepatol Commun. 2025;9(8):e0752.[DOI]

-

122. Zhou J, Zhou Q, Mo Y, Zhang H, Dang R, Lin M, et al. A novel peculiarity of TXNIP reversing the radioresistance of NPC and inducing ferroptosis by xCT-GSH-GPX4-ROS axis. Head Neck. 2026;48(1):134-147.[DOI]

-

123. Nagakannan P, Islam MI, Sultana S, Karimi-Abdolrezaee S, Eftekharpour E. TXNIP promotes ferroptosis through NCOA4 mediated ferritinophagy. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2025;1872(8):120054.[DOI]

-

124. Singh LP, Yumnamcha T, Devi TS. Mitophagy, ferritinophagy and ferroptosis in retinal pigment epithelial cells under high glucose conditions: Implications for diabetic retinopathy and age-related retinal diseases. JOJ Ophthalmol. 2021;8(5):77-85.[DOI]

-

125. Martí-Andrés P, Finamor I, Torres-Cuevas I, Pérez S, Rius-Pérez S, Colino-Lage H, et al. TRP14 is the rate-limiting enzyme for intracellular cystine reduction and regulates proteome cysteinylation. EMBO J. 2024;43(13):2789-2812.[DOI]

-

126. Löfgren S, Fernando MR, Xing KY, Wang Y, Kuszynski CA, Ho YS, et al. Effect of thioltransferase (glutaredoxin) deletion on cellular sensitivity to oxidative stress and cell proliferation in lens epithelial cells of thioltransferase knockout mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49(10):4497-4505.[DOI]

-

127. Meyer LM, Löfgren S, Ho YS, Lou M, Wegener A, Holz F, et al. Absence of glutaredoxin1 increases lens susceptibility to oxidative stress induced by UVR-B. Exp Eye Res. 2009;89(6):833-839.[DOI]

-

128. Guo C, Guo Y, Zhang J, Wang J, Su L, Ning X, et al. Grx2 maintains GSH/GSSG homeostasis to enhance GPX4-mediated ferroptosis defense in UVB irradiation induced cataract. Exp Eye Res. 2025;257:110421.[DOI]

-

129. Aboushousha R, van der Velden J, Hamilton N, Peng Z, MacPherson M, Erickson C, et al. Glutaredoxin attenuates glutathione levels via deglutathionylation of Otub1 and subsequent destabilization of system xC-. Sci Adv. 2023;9(37):eadi5192.[DOI]

-

130. Lorenz SM, Wahida A, Bostock MJ, Seibt T, Santos Dias Mourão A, Levkina A, et al. A fin-loop-like structure in GPX4 underlies neuroprotection from ferroptosis. Cell. 2025.[DOI]

-

131. Ju Y, Zhang Y, Tian X, Zhu N, Zheng Y, Qiao Y, et al. Protein S-glutathionylation confers cellular resistance to ferroptosis induced by glutathione depletion. Redox Biol. 2025;83:103660.[DOI]

-

132. Miyahara S, Ohuchi M, Nomura M, Hashimoto E, Soga T, Saito R, et al. FDX2, an iron-sulfur cluster assembly factor, is essential to prevent cellular senescence, apoptosis or ferroptosis of ovarian cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2024;300(9):107678.[DOI]

-

133. Liu G, Tang R, Wang C, Yu D, Wang Z, Yang H, et al. Bimetallic nanoconjugate hijack Fe-S clusters to drive a closed-loop cuproptosis-ferroptosis strategy for osteosarcoma inhibition. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2026;703(1):139052.[DOI]

-

134. Xiang H, Sun J, Kong L, Wang Y, Qiu X, Zeng J, et al. NDUFA8 promotes cell viability and inhibits ferroptosis and cisplatin sensitivity by stabilizing Fe-S clusters in cervical cancer. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2025;398(11):15547-15559.[DOI]

-

135. Lee J, You JH, Shin D, Roh JL. Inhibition of glutaredoxin 5 predisposes cisplatin-resistant head and neck cancer cells to ferroptosis. Theranostics. 2020;10(17):7775-7786.[DOI]

-

136. Cheng N, Donelson J, Breton G, Nakata PA. Liver specific disruption of glutaredoxin 3 leads to iron accumulation and impaired cellular iron homeostasis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2023;649:39-46.[DOI]

-

137. Camaschella C, Campanella A, De Falco L, Boschetto L, Merlini R, Silvestri L, et al. The human counterpart of zebrafish shiraz shows sideroblastic-like microcytic anemia and iron overload. Blood. 2007;110(4):1353-1358.[DOI]

-

138. Cuccaro R, Masini M, Malanho Silva J, Camponeschi F, Banci L. Human glutaredoxin 3: Multiple domains for a unique function. J Inorg Biochem. 2025;274:113103.[DOI]

-

139. Jordt LM, Gellert M, Zelms F, Bekeschus S, Lillig CH. The thioredoxin-like and one glutaredoxin domain are required to rescue the iron-starvation phenotype of Hela GLRX3 knock out cells. FEBS Lett. 2025;599(16):2334-2345.[DOI]

-

140. Petry SF, Römer A, Rawat D, Brunner L, Lerch N, Zhou M, et al. Loss and recovery of glutaredoxin 5 is inducible by diet in a murine model of diabesity and mediated by free fatty acids in vitro. Antioxidants. 2022;11(4):788.[DOI]

-

141. Zhang HL, Hu BX, Li ZL, Du T, Shan JL, Ye ZP, et al. PKCβII phosphorylates ACSL4 to amplify lipid peroxidation to induce ferroptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2022;24(1):88-98.[DOI]

-

142. Wang Y, Luo W, Shen S, Zhuang Y, Zhu Y, Liu Y, et al. Glaucocalyxin a induces autophagy-mediated ferroptosis by targeting PRDX1 and TXNRD1 proteins in non-small cell lung cancer. Phytomedicine. 2025;148:157280.[DOI]

-

143. Chen H, Zhao J, Kang Y, Wang S, Qin D, Yu L, et al. PFGA12 ameliorates Hypoxic-Ischemic brain injury by directly regulating PRDX1 and inhibiting ferroptosis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2025;242(2):117307.[DOI]

-

144. Lai W, Zhu W, Wu J, Huang J, Li X, Luo Y, et al. HJURP inhibits sensitivity to ferroptosis inducers in prostate cancer cells by enhancing the peroxidase activity of PRDX1. Redox Biol. 2024;77:103392.[DOI]

-

145. Li L, Yuan Q, Chu YM, Jiang HY, Zhao JH, Su Q, et al. Advances in holliday junction recognition protein (HJURP): Structure, molecular functions, and roles in cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2023;11:1106638.[DOI]

-

146. Fan X, Liu F, Wang X, Wang Y, Chen Y, Shi C, et al. LncFASA promotes cancer ferroptosis via modulating PRDX1 phase separation. Sci China Life Sci. 2024;67(3):488-503.[DOI]

-

147. Liu X, Zeng L, Liu J, Huang Y, Yao H, Zhong J, et al. Artesunate induces ferroptosis in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cells by targeting PRDX1 and PRDX2. Cell Death Dis. 2025;16(1):513.[DOI]

-

148. Lin C, Xie S, Wang M, Shen J. PRDX1 knockdown promotes erastin-induced ferroptosis and impedes diffuse large B-cell lymphoma development by inhibiting the MAPK/ERK pathway. BMC Cancer. 2025;25(1):806.[DOI]

-

149. Song Y, Wang X, Sun Y, Yu N, Tian Y, Han J, et al. PRDX1 inhibits ferroptosis by binding to Cullin-3 as a molecular chaperone in colorectal cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 2024;20(13):5070-5086.[DOI]

-

150. Zhang J, Zhang M, Tatar M, Gong R. Keap1-independent Nrf2 regulation: A novel therapeutic target for treating kidney disease. Redox Biol. 2025;82:103593.[DOI]

-

151. Chen P, Chen Z, Zhai J, Yang W, Wei H. Overexpression of PRDX2 in adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells enhances the therapeutic effect in a neurogenic erectile dysfunction rat model by inhibiting ferroptosis. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2023,2023(1);4952857.[DOI]

-

152. Yin L, Deng Z, Liu J, Ye L, Huang J, Dai Y, et al. Keratin 20 suppresses exosomal secretion of peroxiredoxin 2 and ferroptosis in acute kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2025.[DOI]

-

153. Lin TC. RUNX2 and cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(8):7001.[DOI]

-

154. Huang J, Jia R, Guo J. RUNX2 isoform II protects cancer cells from ferroptosis and apoptosis by promoting PRDX2 expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Elife. 2025;13:RP99122.[DOI]

-

155. Guan G, Liu J, Zhang Q, He M, Liu H, Chen K, et al. NFAT5 exacerbates β-cell ferroptosis by suppressing the transcription of PRDX2 in obese type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2025;82(1):64.[DOI]

-

156. Cui S, Ghai A, Deng Y, Li S, Zhang R, Egbulefu C, et al. Identification of hyperoxidized PRDX3 as a ferroptosis marker reveals ferroptotic damage in chronic liver diseases. Mol Cell. 2023;83(21):3931-3939.[DOI]

-

157. Cardozo G, Mastrogiovanni M, Zeida A, Viera N, Radi R, Reyes AM, et al. Mitochondrial peroxiredoxin 3 is rapidly oxidized and hyperoxidized by fatty acid hydroperoxides. Antioxidants. 2023;12(2):408.[DOI]

-

158. Cordray P, Doyle K, Edes K, Moos PJ, Fitzpatrick FA. Oxidation of 2-Cys-peroxiredoxins by arachidonic acid peroxide metabolites of lipoxygenases and cyclooxygenase-2. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(45):32623-32629.[DOI]

-

159. Whitaker HC, Stanbury DP, Brinham C, Girling J, Hanrahan S, Totty N, et al. Labeling and identification of LNCaP cell surface proteins: A pilot study. Prostate. 2007;67(9):943-954.[DOI]

-

160. Rhee SG, Kil IS. Mitochondrial H2O2 signaling is controlled by the concerted action of peroxiredoxin III and sulfiredoxin: Linking mitochondrial function to circadian rhythm. Free Radic Biol Med. 2016;100:73-80.[DOI]

-

161. Hanschmann EM, Lönn ME, Schütte LD, Funke M, Godoy JR, Eitner S, et al. Both thioredoxin 2 and glutaredoxin 2 contribute to the reduction of the mitochondrial 2-Cys peroxiredoxin Prx3. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(52):40699-40705.[DOI]

-

162. Guo S, Zhang D, Dong Y, Shu Y, Wu X, Ni Y, et al. Sulfiredoxin-1 accelerates erastin-induced ferroptosis in HT-22 hippocampal neurons by driving heme Oxygenase-1 activation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2024;223:430-442.[DOI]

-

163. Zhao X, Peng Y, Wang M, Tan Q. Methylation of PRDX3 expression alleviate ferroptosis and oxidative stress in patients with osteoarthritis cartilage injury. Arch Rheumatol. 2025;40(2):197-210.[DOI]

-

164. Xu S, Liu Y, Yang S, Fei W, Qin J, Lu W, et al. FXN targeting induces cell death in ovarian cancer stem-like cells through prdx3-mediated oxidative stress. iScience. 2024;27(8):110506.[DOI]

-

165. Chen Y, Peng X, Feng Z, Zhang L, Bai J, Li Y, et al. Peroxiredoxins as novel indicators in multiple myeloma associated with ferroptosis and immune infiltration. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):32765.[DOI]

-

166. Wan S, Li KP, Chen SY, Wang CY, Cheng K, Yang JW, et al. Single-cell sequencing combined with urinary multi-omics analysis reveals that the non-invasive biomarker PRDX5 regulates bladder cancer progression through ferroptosis signaling. BMC Cancer. 2025;25(1):533.[DOI]

-

167. Zhao JZ, Li YF, Yuan FK, Zhao ML, Han YW, Wang JX, et al. Okanin suppresses the growth of colorectal cancer cells by targeting at peroxiredoxin 5. Adv Sci. 2025;12(43):e17148.[DOI]

-

168. Tao Y, Fu S, Lu J, Fu B, Liu S, Li L. Salvianolic acid B attenuates ferroptosis in acute kidney injury by targeting PRDX5. FASEB J. 2025;39(14):e70803.[DOI]

-

169. Liu J, Sun L, Chen D, Huo X, Tian X, Li J, et al. PRDX6-induced inhibition of ferroptosis in epithelial cells contributes to liquiritin-exerted alleviation of colitis. Food Funct. 2022;13(18):9470-9480.[DOI]

-

170. Xiong J, Zhou R, Deng X. PRDX6 alleviated heart failure by inhibiting doxorubicin-induced ferroptosis through the JAK2/STAT1 pathway inactivation. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2024;60(4):354-364.[DOI]

-

171. Zhang Q, Hu Y, Hu JE, Ding Y, Shen Y, Xu H, et al. Sp1-mediated upregulation of Prdx6 expression prevents podocyte injury in diabetic nephropathy via mitigation of oxidative stress and ferroptosis. Life Sci. 2021;278:119529.[DOI]

-

172. Torres-Velarde JM, Allen KN, Salvador-Pascual A, Leija RG, Luong D, Moreno-Santillán DD, et al. Peroxiredoxin 6 suppresses ferroptosis in lung endothelial cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2024;218:82-93.[DOI]

-

173. Liao J, Xie SS, Deng Y, Wu DD, Meng H, Lan WF, et al. PRDX6-mediated pulmonary artery endothelial cell ferroptosis contributes to monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension. Microvasc Res. 2023;146:104471.[DOI]

-

174. Liang J, Liu Z, He Y, Li H, Wu W. Methyltransferase ZC3H13 regulates ferroptosis of alveolar macrophages in sepsis-associated acute lung injury via PRDX6/P53/SLC7A11 axis. Funct Integr Genomics. 2025;25(1):156.[DOI]

-

175. Wei T, Wang X, Lang K, Song Y, Luo J, Gu Z, et al. Peroxiredoxin 6 protects pulmonary epithelial cells from cigarette-related ferroptosis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Inflammation. 2025;48(2):662-675.[DOI]

-