Abstract

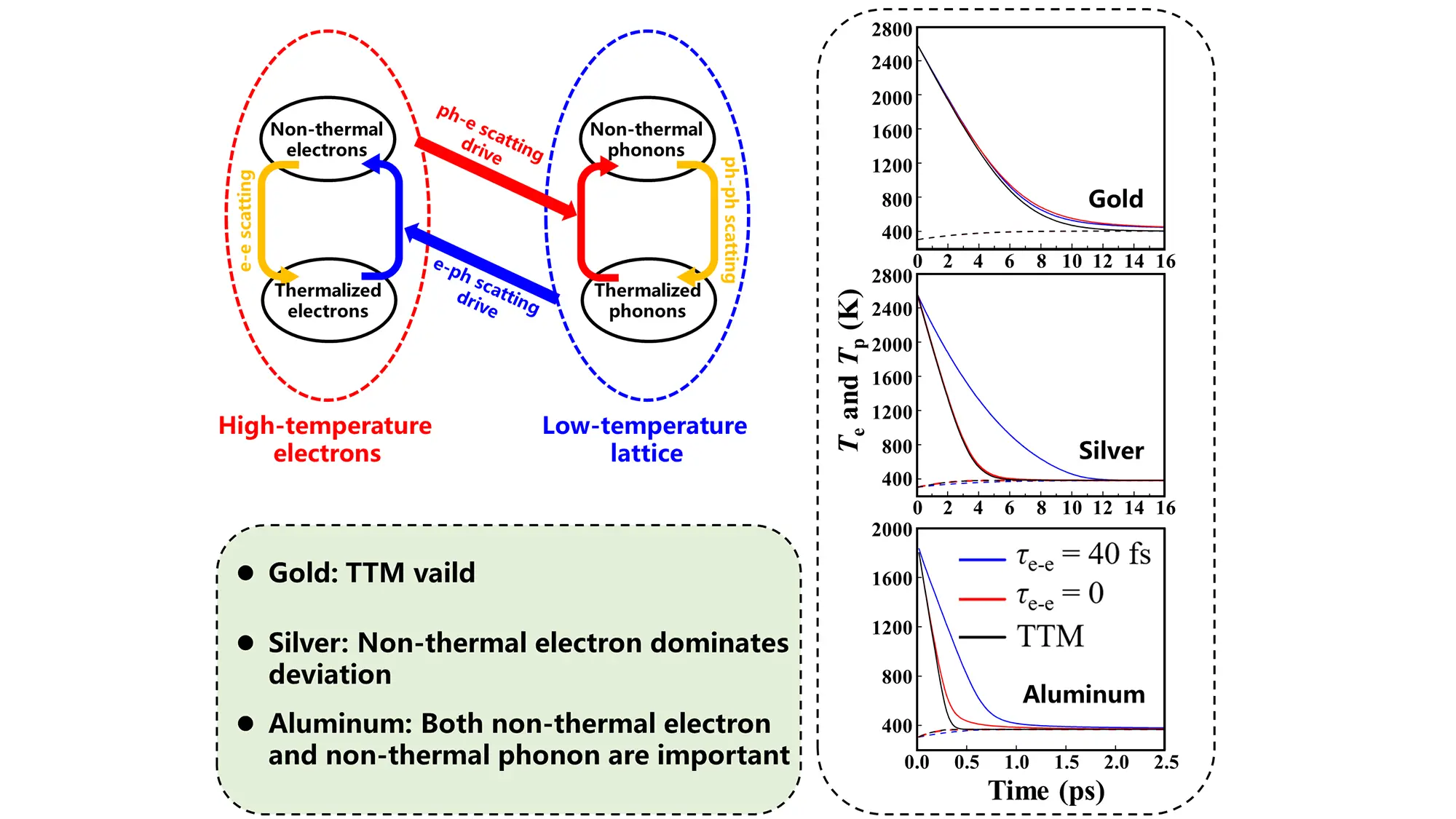

The two-temperature model (TTM) has been widely employed in describing ultrafast relaxation dynamics, providing a simple yet powerful framework to study energy relaxation in photoexcited systems. Recently, the time-dependent Boltzmann equation (TDBE) has revealed the limitations of TTM. However, current implementations of the TDBE assume instantaneous electronic thermalization. In this work, we employ first-principles Boltzmann transport simulations to explicitly examine the impact of non-thermal electronic distributions on relaxation processes. By comparing gold, silver, and aluminum as representative cases, we show that while phonons can indeed remain far from equilibrium, the neglect of non-thermal electrons is far more consequential. For gold, the absence of strongly coupled scattering channels makes the influence of non-thermal electrons negligible, rendering the TTM valid. For silver, deviations from the TTM stem mainly from non-thermal electronic effects, and for aluminum, both non-thermal electrons and phonons lead to substantial discrepancies. These findings demonstrate that non-thermalized electrons play a decisive role in out-of-equilibrium ultrafast energy transfer between electrons and phonons, offering a new perspective on the limitations of the TTM.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

1. Introduction

In recent years, the rapid development of pump-probe femtosecond spectroscopy has enabled the observation of intriguing phenomena on sub-picosecond timescales[1-7]. For example, ultrafast electron diffuse scattering provides direct access to the dynamics of the crystalline lattice and electron-phonon (e-ph) interactions with time and momentum resolution[8-14], enabling a detailed understanding of energy transfer between hot electrons and phonons. During ultrafast processes, the system can be described as hot electrons transferring energy to a cold phonon bath via e-ph coupling. The well-known two-temperature model (TTM) provides a simple theoretical framework to describe this relaxation process, assuming that both the electron and phonon subsystems are always thermalized and characterized by distinct Fermi-Dirac (FD) and Bose-Einstein (BE) distributions at different temperatures[15-17]. Within the TTM, the rate of energy transfer from electrons to phonons is governed by the electron-phonon coupling constant (Gep), and an important implication is the connection between Gep and the coupling constant λ used in the Eliashberg generalization of Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer (BCS) theory[18]. This relationship allows λ to be extracted from pump-probe measurements, and interestingly, for several metals, the values of λ obtained in this way have shown good agreement with other independent methods, supporting the validity of the TTM[19].

However, numerous theoretical calculations suggest that phonon lifetimes are typically on the order of picoseconds, which makes it unlikely for the phonon subsystem to reach thermal equilibrium on a sub-picosecond timescale[20-26]. On the other hand, experimental results also indicate that the internal thermalization timescale for non-thermal electrons can be on the order of several hundred femtoseconds[27-29]. These observations imply that the assumption of instantaneous thermalization of either subsystem is questionable, fundamentally challenging the basic premises of the TTM.

To gain deeper insights into the contradiction of the TTM, we combine density functional theory (DFT) calculations of e-ph and phonon-phonon (ph-ph) scattering rates with the time-dependent Boltzmann transport equation (TDBE) to investigate the time evolution of electrons and phonons under non-equilibrium conditions. Similar approaches have been applied to systems such as graphene[30], MoS2 monolayer[31], FePt[32], and other metals and semiconductors[20,33]. These studies assume instantaneous electron thermalization and focus exclusively on the iterative evolution of the phonon distribution. This assumption is based on the fact that non-thermal electron features are observed experimentally only on femtosecond timescales, while electrons appear fully thermalized during picosecond-scale dynamics. Nevertheless, we argue that electrons can still retain localized non-thermal features under the influence of a cold phonon bath and play an important role in relaxation, because the separation between e-ph and electron-electron (e-e) scattering timescales is not always obvious. Therefore, in this work, we solve the coupled Boltzmann equations for both electrons and phonons, focusing on how non-thermal electrons and phonons together affect the ultrafast relaxation dynamics. We focus on the out-of-equilibrium dynamics in gold, silver, and aluminum. Our results reveal that even when electrons initially follow a thermal FD distribution, they can deviate substantially from the FD distribution during the relaxation process. Therefore, it becomes necessary to consider this non-thermal distribution explicitly for a quantitative understanding of the ultrafast e-ph relaxation dynamics.

2. Method

2.1 Theory of time-dependent Boltzmann transport equation

The distributions of electron (fmk) and phonon (nsq) evolve over time, and their dynamics are described by the TDBE[34]:

where the right-hand side of the equations represents the collision integrals, and A/B correspond to the emission/absorption process. Here, e-ph scattering is considered for electrons, whereas both phonon-electron (ph-e) and ph-ph scattering are considered for phonons. The expressions can be written as:

where

For e-e scattering, we employ the RTA:

where the first term on the right-hand side is given by Eq. (1), τe-e is the relaxation time of e-e thermalization, and

where εmk is the energy of electron states, μ is the chemical potential, Δte is the electronic iteration time step, and Te is the average temperature of electrons. Eq. (7) is solved by employing the Lie-Trotter splitting scheme in combination with the Euler method.

Importantly, to compare with previous TDBE studies without non-thermal electrons, we consider resetting the electron distribution to the FD form immediately after each electronic time step (labeled as τe-e = 0). In this case, Eq. (7) is expressed as

where

where ωsq is phonon energy, Tp is the average temperature of phonons, and

2.2 Electron-phonon coupling constant

In the TTM framework, the energy exchange between electrons and phonons is described by

where Ce is the electronic heat capacity, Te and Tp are the electron and phonon temperatures, respectively. The left-hand term can be expressed as the rate of change of the total energy of electrons

where εmk is the energy of electron states, μ is the chemical potential, and

2.3 Mode-dependent effective electron temperature

To quantitatively characterize the deviation of nonequilibrium electrons from the FD distribution, a mode-dependent effective electron temperature (Tmk) is introduced

where εmk is the energy of electron states and μ is the chemical potential. When the electronic distribution approaches the FD distribution, Tmk for all states converges to a single value. In contrast, away from thermal distribution, Tmk becomes broadened, and the extent of this broadening can serve as a measure of deviation from the thermalized distribution.

2.4 Workflow

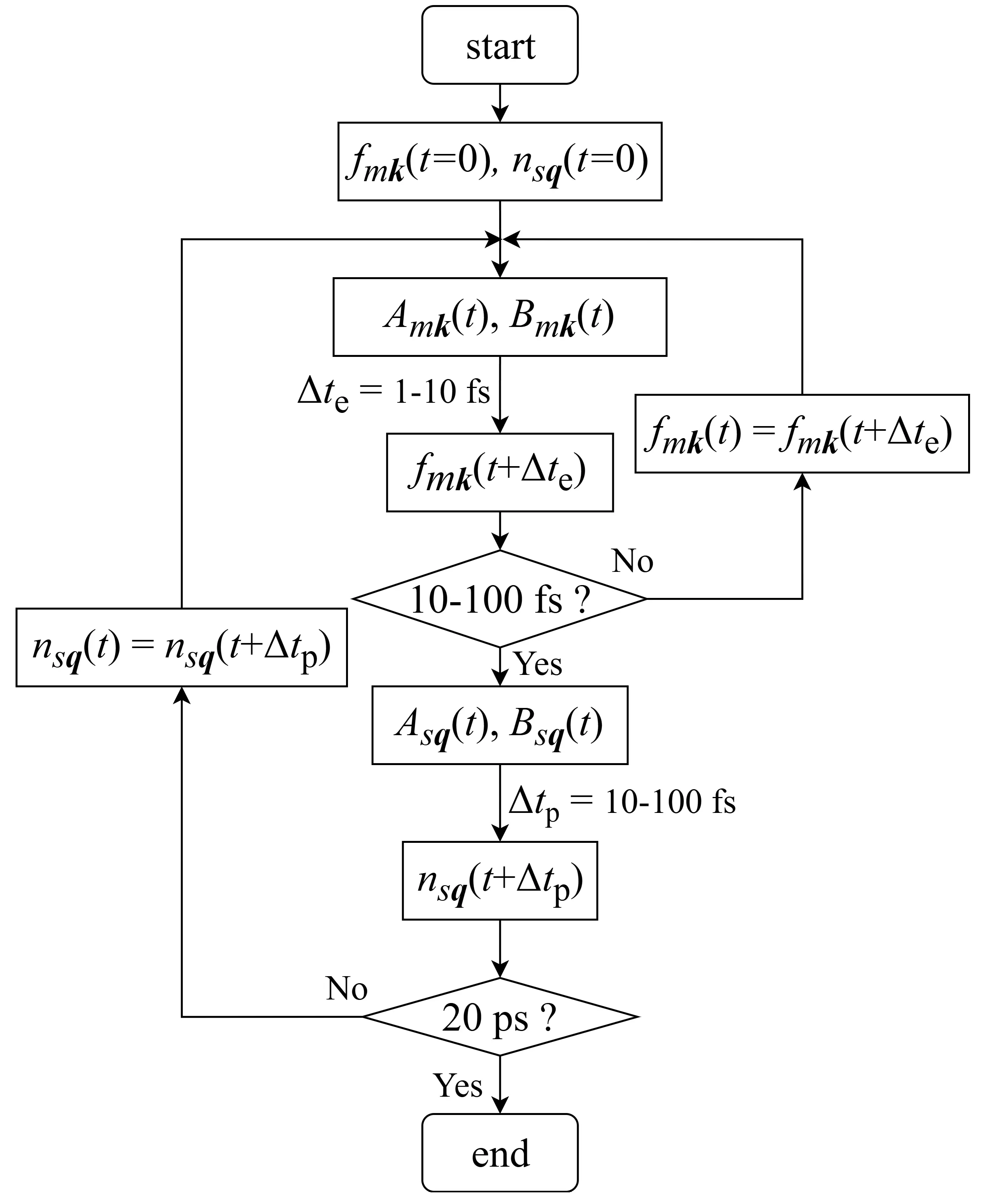

As shown in Figure 1, a high-temperature FD distribution for electrons and a low-temperature BE distribution for phonons are used as the initial distributions to calculate the Amk and Bmk, which are implemented by the EPW package[35]. Next, we solve for the electron distribution function using the Euler method. Considering that the relaxation time of ph-ph scattering is several orders of magnitude longer than that of e-ph scattering, we first iterate the electron distribution function for 10-100 fs before starting the iteration of the phonon distribution. The calculation of the Asq and Bsq employs both the EPW and ShengBTE packages[36].

2.5 Computational details

All electronic structures were computed using the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) exchange-correlation functional, using fully relativistic norm-conserving pseudopotentials, as implemented in the Quantum Espresso package[37-39]. A 90 Ry cutoff energy was adopted, and the Brillouin zone was sampled with a 10 × 10 × 10 Monkhorst-Pack grid, with Gaussian smearing with 0.01 Ry. The phonon dispersion was computed using density functional perturbation theory and a 5 × 5 × 5 q-grid[40]. The e-ph scattering matrix elements on a dense mesh of 20 × 20 × 20 k-points and 20 × 20 × 20 q-points were obtained using the Bloch-Wannier-Bloch transformation, with 16, 18, and 24 maximally localized Wannier functions for gold, silver, and aluminum, respectively[41,42]. The fitted electronic and phononic band structures are shown in Figure S1,S2,S3, and the convergence of the relaxation dynamics with k-/q- grid in gold is shown in Figure S4. The electron distribution was iterated using the Lie-Trotter splitting scheme and the explicit Euler method with a time step (Δte) of 2 fs for gold and aluminum, and the implicit counterpart with Δte of 10 fs for silver. The third-order force constants were computed using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package and the Thirdorder package on a 3 × 3 × 3 supercell[36,43]. An energy cutoff of 600 eV was used with PAW-PBE pseudopotentials[37,44]. The ph-ph scattering matrix elements were calculated using the ShengBTE package[36]. The phonon distribution was iterated using the explicit Euler method with a time step (Δtp) of 0.02 ps for aluminum, and 0.1 ps for gold and silver.

3. Results and Discussion

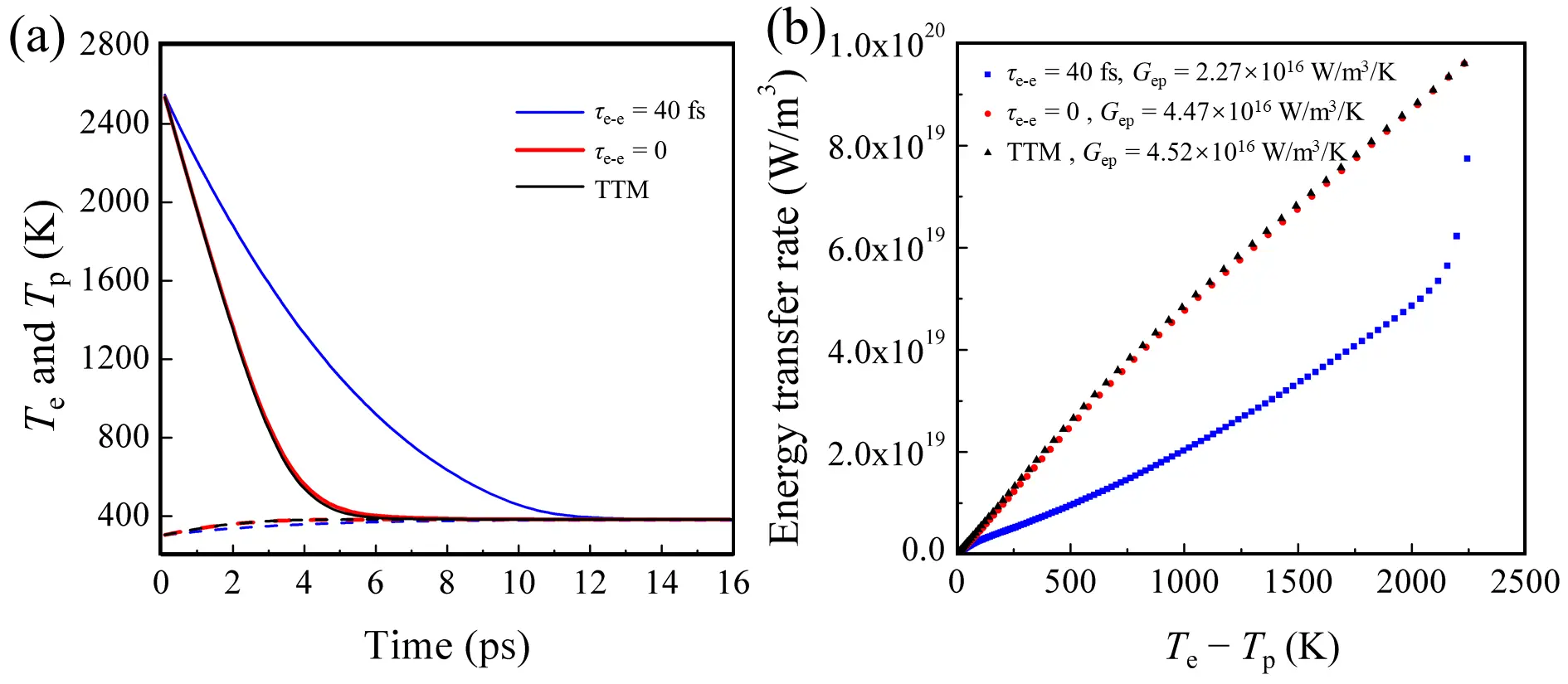

3.1 Out-of-equilibrium dynamics in gold

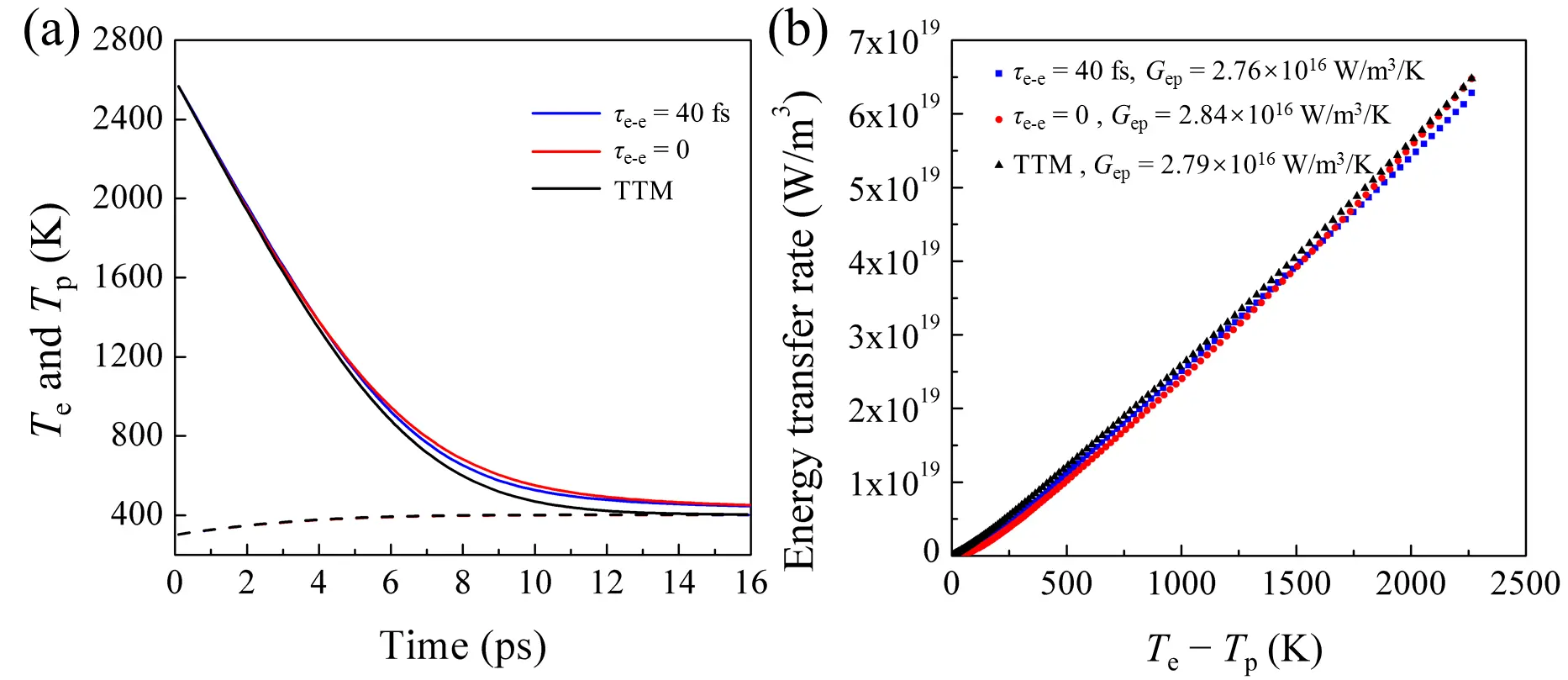

To compare with the results of time domain thermoreflectance (TDTR) experiments, we compute the dynamics of the electron and phonon systems with an initial Te of 2,600 K and Tp of 300 K[45]. During the relaxation process, the concept of temperature is not directly applicable to non-equilibrium distributions. Therefore, the average electron and phonon temperatures are obtained by fitting the thermalized distributions, with energy conservation and electron number conservation enforced via the chemical potential (see Eqs. (8), (9), and (11)). Figure 2a shows the time evolution of Te and Tp in gold under three conditions: τe-e = 40 fs, τe-e = 0 (instantaneous electron thermalization), and the TTM (instantaneous electron and phonon thermalization). The comparison reveals that whether the electron distribution is constrained to a FD distribution or the phonon distribution to a BE distribution, the overall relaxation behavior remains qualitatively similar. The main difference is the timescale for reaching equilibrium: in the TTM, the system equilibrates within approximately 12 ps, whereas in the other two cases, equilibrium is delayed to several tens of picoseconds due to the slower ph-ph scattering process (Figure S5).

Figure 2. (a) Electron Te (solid lines) and phonon Tp (dashed lines) temperatures during relaxation in gold; (b) Energy transfer rate from electrons to phonons as a function of the temperature difference. The Gep in the TTM is determined from the slope of a linear fit. TTM: two-temperature model.

In Figure 2b, we plot the energy transfer rate from electrons to phonons as a function of the temperature difference between the two subsystems. The slope corresponds to Gep as defined in the TTM. The fitted Gep is 2.76 × 1016, 2.84 × 1016, and 2.79 × 1016 W/m3/K for τe-e = 40 fs, τe-e = 0, and TTM, respectively. These results are slightly larger than reported values (~2.2 × 1016 W/m3/K)[46-48]. To examine this discrepancy, we compute the electronic heat capacity as a function of Te during relaxation (Figure S6). The fitted electron specific heat constant (76.3 J/m3/K2) also slightly exceeds experimental measurements (67.6 J/m3/K2)[49-51], indicating an overestimation of the electronic eigenvalues. Nevertheless, all deviations remain below 15%, supporting the accuracy of our calculations.

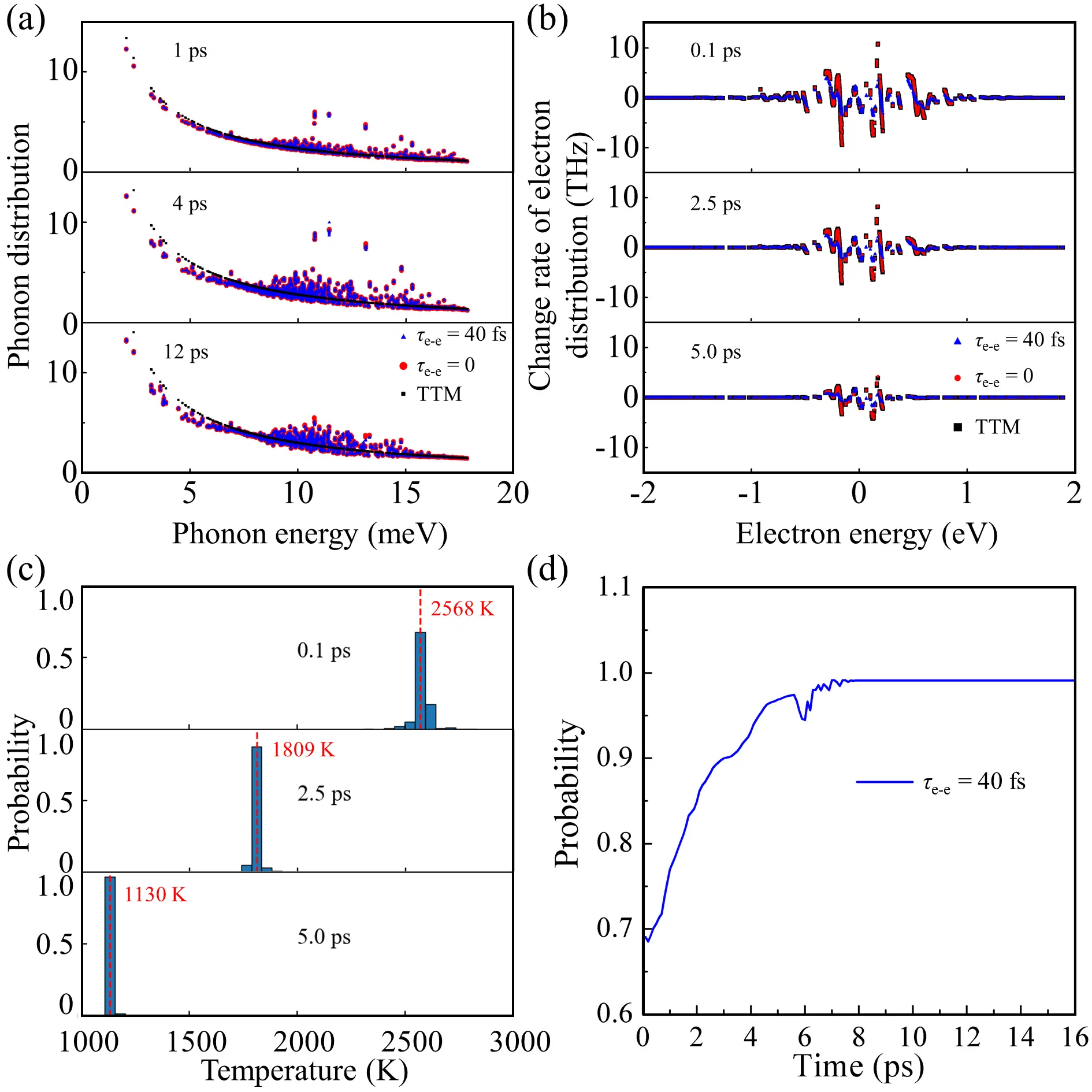

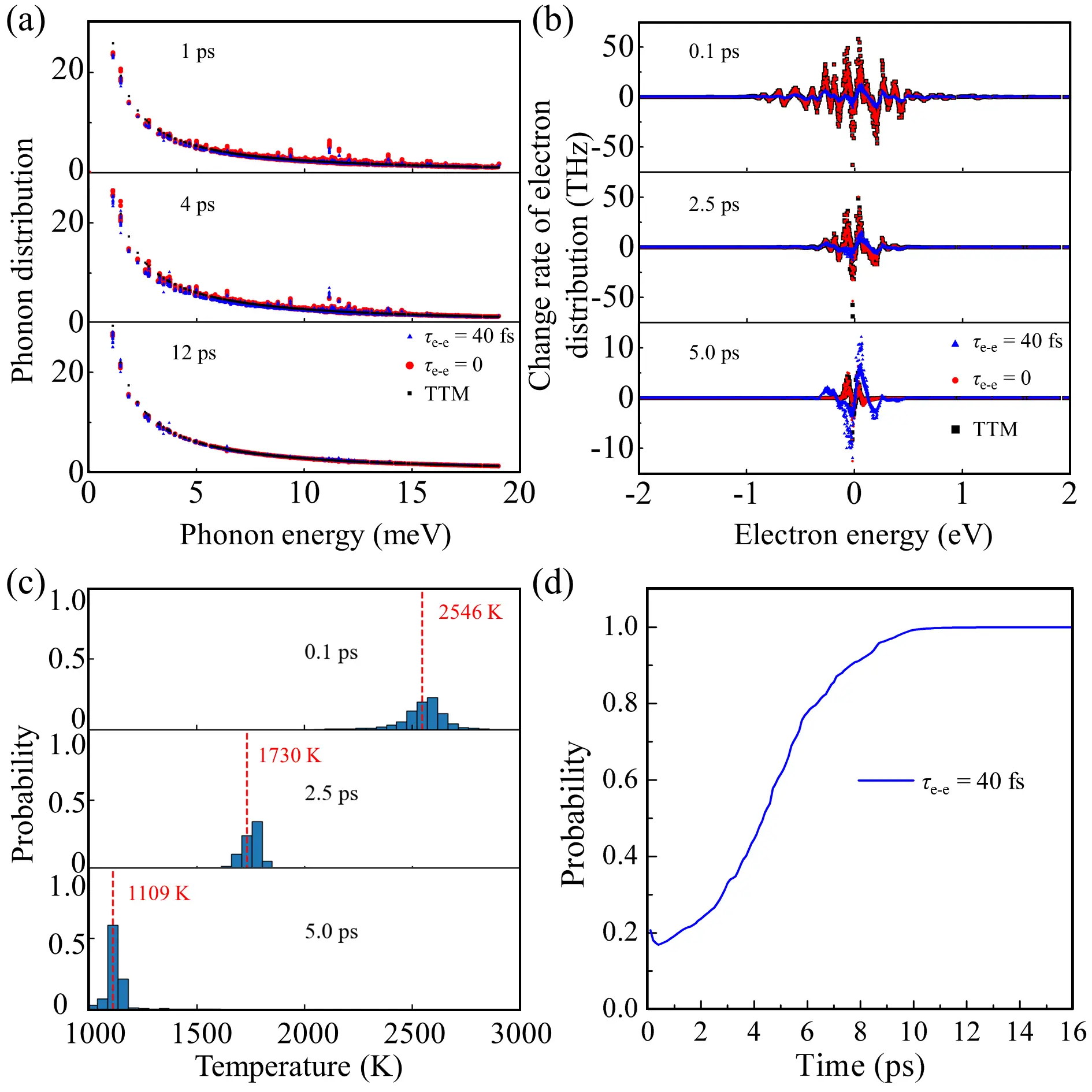

The difference between τe-e = 0 and TTM is relatively small, even though the phonons are confirmed to remain in a non-equilibrium state within 12 ps (Figure 3a), consistent with previous reports[20,33]. Surprisingly, the results at τe-e = 40 fs also exhibit no significant deviation, which seems to indicate that the impact of non-thermal electrons on the dynamics may be negligible. To address this issue, we compare the rate of change of the electronic occupation and the distribution of Tmk at different times (Figure 3b,c). The rate of change in electron occupations for τe-e = 0 is nearly identical to that in the TTM case and slightly larger than that for τe-e = 40 fs. This indicates that when the electron distribution is constrained to a FD distribution, the influence of the non-thermal phonon distribution on the overall dynamics is minimal. Moreover, after the first Δtp (0.1 ps), the distribution of Tmk already exhibits a noticeable broadening, indicating that electrons starting from a FD distribution quickly evolve into a non-thermal state through e-ph scattering. After 5 ps, the broadening becomes almost invisible, which is fully consistent with the assumptions of the TTM. These behaviors of electrons can be attributed to the weak e-ph coupling, as well as the lack of strong scattering channels. As a result, over 70% of the electrons have Tmk within 25 K of the average temperature (Figure 3d). Considering only electronic states within a ±2 eV window around the chemical potential, this value is already high, and it would increase further if a larger energy range were included. This indicates that the average temperature is representative of the collective behavior of most electrons.

Figure 3. (a) Phonon distribution and (b) rate of change of the electron distribution at different times during relaxation in gold. The chemical potential is set to zero; (c) Effective temperature distribution of electronic states within ± 2 eV around the chemical potential at different times during τe-e = 40 fs relaxation in gold. The vertical axis represents the probability of electronic states falling within each 50 K temperature interval. The red dashed line indicates the current average temperature; (d) Time evolution of the probability that electronic states within ± 2 eV of the chemical potential fall within ± 25 K of the average temperature in gold, under the condition of τe-e = 40 fs.

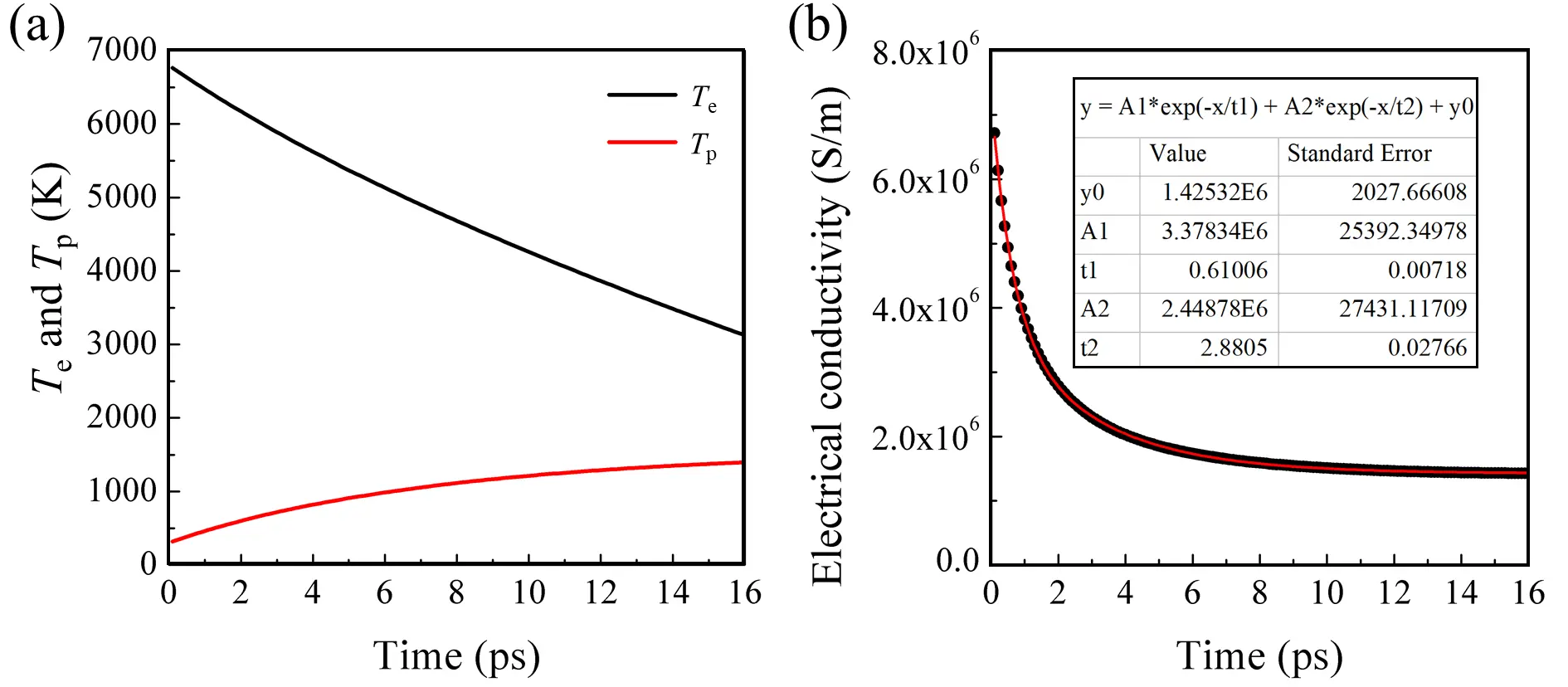

Since gold is a case where the TTM remains valid, we assume instantaneous electron thermalization (τe-e = 0) to compute the conductivity, aiming to verify the accuracy of our calculations. The electron absorption and emission coefficients at each time step yield the instantaneous scattering rates, which are then used in the Boltzmann transport expression within the RTA to obtain the conductivity evolution. Experimentally, the conductivity evolution has been measured for initial Te exceeding 16,000 K[52]. Such high Te in DFT calculations significantly increase the number of electronic states within the Fermi window, leading to a greater number of e-ph scattering processes and an increase in Gep by an order of magnitude[51,53]. At the same time, it can induce lattice melting, and many works have shown that in this regime the Gep obtained from theory deviates markedly from experimental values[54,55]. Thus, the initial Te and Tp were set to 6,800 K and 300 K, respectively. The resulting time dependence of the temperatures and conductivity is shown in Figure 4. The Tp reaches the melting point of gold (~1,337 K) at 13.5 ps. The conductivity is in good agreement with a bi-exponential decay model, with relaxation times of 0.6 ps and 2.9 ps, respectively. The magnitude and trend of the conductivity are consistent with experimental observations, however, due to differences in the initial conditions, our results still require further validation[52].

Figure 4. (a) Electron (Te) and phonon (Tp) temperatures and (b) electrical conductivity during relaxation, with initial electron and phonon temperatures of 6,800 K and 300 K, respectively. The table in (b) summarizes the fitting formula, parameters, and their standard errors.

3.2 Out-of-equilibrium dynamics in silver

The instantaneous electron thermalization reproduces the relaxation dynamics in gold owing to its weak e-ph coupling. However, this agreement is not generally applicable to other metals. We next examine the case of silver. To enable a direct comparison with gold, the same initial temperatures (2,600 K for electrons and 300 K for phonons) were assigned to the silver system. In Figure 5a, the relaxation processes for τe-e = 0 and the TTM are nearly identical, with the system approaching equilibrium after approximately 7 ps. In contrast, for τe-e = 40 fs, relaxation is much slower, reaching equilibrium around 12 ps. This indicates that when the electronic distribution is far from equilibrium, the energy transfer rate and the corresponding Gep are reduced, as evidenced in Figure 5b. The slope remains nearly constant for the τe-e = 0 and TTM cases (corresponding to 4.47 × 1016 W/m3/K and 4.52 × 1016 W/m3/K, respectively), whereas for τe-e = 40 fs, a drop appears when the temperature difference is around 2,200 K. This suggests that using FD and BE distributions may overestimate the energy transfer rate, and as the electrons deviate from equilibrium, the Gep converges to a lower constant value (2.27 × 1016 W/m3/K). The reported Gep for silver (2.5-3.5 × 1016 W/m3/K[28,51,56,57]) is between the results for τe-e = 0 and τe-e = 40 fs, suggesting that the actual electron thermalization rate is not instantaneous, but still faster than what is assumed in our τe-e = 40 fs case.

Figure 5. (a) Electron Te (solid lines) and phonon Tp (dashed lines) temperatures during relaxation in silver; (b) Energy transfer rate from electrons to phonons as a function of the temperature difference. The Gep is determined as the slope of a linear fit.

To further understand these results, we present the phonon distribution functions, the change rate of the state-resolved electron occupations, and the distribution of Tmk in Figure 6. A large difference is observed between τe-e = 40 fs and τe-e = 0 (Figure 6a). This behavior was not seen in gold (Figure 3a). More notably, phonons across the whole frequency spectrum deviate from equilibrium in silver, whereas the deviations are primarily limited to high-frequency modes in gold. This suggests that silver possesses a broader e-ph scattering phase space and more complex scattering channels, rendering the energy transfer process more sensitive to the details of the electronic distribution. As for the electrons, the change rates of nearly all electrons in the τe-e = 40 fs case are around one order of magnitude smaller than those in the other two cases (Figure 3b). The comparison between τe-e = 0 and the TTM shows nearly identical electron occupation change rates, consistent with our observations in gold. This reinforces the conclusion that, if electrons thermalize instantaneously, the influence of the phonon non-thermal distribution on the relaxation dynamics is negligible. Moreover, when comparing τe-e = 40 fs to τe-e = 0, we observe that the sign of the change rate for some electron states even reverses, indicating a shift in the dominant e-ph scattering mechanism, from emission to absorption or vice versa.

Figure 6. (a) Phonon distribution and (b) change rate of electron distribution at different times during relaxation in silver. The chemical potential is set to zero; (c) Effective temperature distribution of electronic states within ± 2 eV around the chemical potential at different times during τe-e = 40 fs relaxation in silver. The vertical axis represents the probability of electronic states falling within each 50 K temperature interval. The red dashed line indicates the current average temperature; (d) Time evolution of the probability that electronic states within ± 2 eV of the chemical potential fall within ± 25 K of the average temperature in silver, under the condition of τe-e = 40 fs.

In Figure 6c,d, the broadening of Tmk is much larger than that in gold, and a pronounced broadening is still observed even at 5 ps, by which time the TTM predicts the system to be nearly equilibrated, thereby leading to a significant deviation. The reason is that certain strongly e-ph scattering channels cause the corresponding electronic states to deviate significantly from equilibrium, and electronic thermalization cannot be completed prior to e-ph scattering due to the comparable timescales of e-ph and e-e scattering. Thus, although silver and gold exhibit similar Gep values, indicating weak e-ph coupling in both systems, the contrasting Tmk broadening reveals that the fundamental e-ph scattering mechanisms are different.

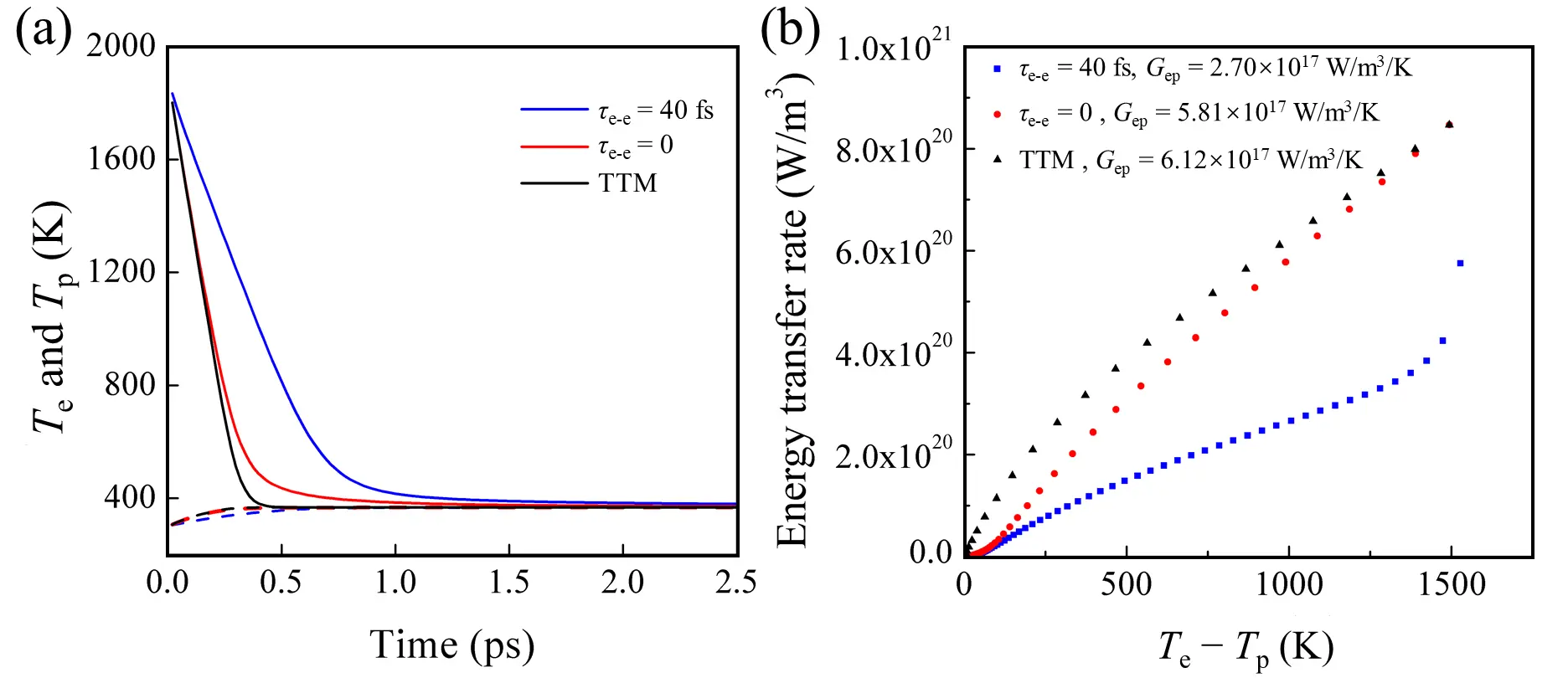

3.3 Out-of-equilibrium dynamics in aluminum

Unlike gold and silver, aluminum exhibits much stronger e-ph coupling, with the experimental Gep exceeding that of gold and silver by an order of magnitude[57,58]. Moreover, the experimentally determined Gep shows a noticeable deviation from TTM predictions[59]. Herein, we examine the relaxation process for initial Te of 1,900 K and Tp of 300 K (Figure 7). The relaxation processes for τe-e = 0 and the TTM are in close agreement, whereas τe-e = 40 fs exhibits a slower relaxation, consistent with the observations in silver. Owing to the stronger e-ph coupling in aluminum, the Te approaches its equilibrium value within 0.5~1.5 ps, markedly faster than in gold and silver. The τe-e = 0 and TTM results agree with the calculations of Ritzmann et al., in which the Te was found to peak at 1,800 K and approach equilibrium within ~0.7 ps[20]. In contrast, TDTR measurements revealed that the Te relaxed from about 1900 K to equilibrium over ~1.5 ps, consistent with our τe-e = 40 fs results but significantly longer than the TTM prediction[45]. In Figure 7b, the fitted Gep values are 2.7 × 1017, 5.8 × 1017, and 6.1 × 1017 W/m3/K for τe-e = 40 fs, τe-e = 0 and TTM, respectively. The Gep for τe-e = 0 and TTM are significantly larger than that for τe-e = 40 fs, and the latter is consistent with the experimental result of 2.5 × 1017 W/m3/K[58].

Figure 7. (a) Electron Te (solid lines) and phonon Tp (dashed lines) temperatures during relaxation in aluminum; (b) Energy transfer rate from electrons to phonons as a function of the temperature difference. The Gep is determined as the slope of a linear fit.

Notably, the relaxation process in aluminum reveals that not only non-thermal electrons reduce the energy transfer efficiency, but non-thermal phonons also introduce a considerable effect compared to the TTM prediction, which is not observed in gold or silver. To understand this result, we present the phonon distribution functions and the change rate of the state-resolved electron occupations in Figure 8. For τe-e = 40 fs and τe-e = 0, high-frequency phonons are rapidly excited after 0.1 ps (Figure 8a). At 0.3 ps, the low-frequency phonons also exhibit significant deviations from a thermalized BE distribution, indicating that ph-ph scattering has already become the primary mechanism governing internal energy redistribution. At 0.6 ps, the phonon distribution over the entire spectrum exhibits an obvious non-thermal character.

Figure 8. (a) Phonon distribution and (b) change rate of electron distribution at different times during relaxation in aluminum. The chemical potential is set to zero.

Moreover, Figure 8b shows that the electron distribution change for τe-e = 40 fs is about one order of magnitude smaller than that for τe-e = 0 case after 0.02 ps. The peak positions of the distribution change in the two cases remain nearly identical, indicating that the dominant scattering channels are robust. When electrons are assumed to thermalize instantaneously (τe-e = 0), phonon emission through these channels proceeds without restriction. In contrast, a finite thermalization rate leads to a bottleneck in the phonon excitation process, as the initial electron states become depleted while the final states become occupied. Consequently, phonon excitation is significantly faster in the τe-e = 0 case compared to the τe-e = 40 fs case (Figure 8a).

In addition, for τe-e = 40 fs, certain phonon modes exhibit occupations lower than the thermalized BE distribution, which is absent in the τe-e = 0 case. This indicates that the effect is not driven by ph-ph scattering but instead originates from the non-thermal electrons. The non-thermal electrons activate additional e-ph scattering channels that facilitate a reverse flow of energy from phonons back to electrons. At 0.6 ps, the emergence of extra high-frequency peaks in the phonon spectrum for τe-e = 40 fs arises from these additional scattering channels (Figure 8a). The resulting changes in high-frequency phonons further affect the low-frequency modes through ph-ph interactions. Therefore, non-thermal electrons exert a significant influence on the microscopic scattering dynamics, resulting in the distinctly different relaxation behaviors between τe-e = 40 fs and τe-e = 0 cases.

On the other hand, when comparing τe-e = 0 with the TTM case, Figure 8b shows that the electron distribution changes remain nearly identical at 0.02 ps, since the phonon subsystem is still close to equilibrium at this early stage. However, at 0.3 ps, the change rate of electron distribution for τe-e = 0 becomes smaller than that predicted by the TTM. At this time, the high-frequency phonons hold much higher occupations than those required for a thermal phonon distribution in the TTM. According to Eqs. (3) and (4), the electron emission and absorption coefficients (Amk and Bmk) scale positively with the phonon occupation. Consequently, non-thermal high-frequency phonons enhance both coefficients. For the unoccupied electronic states above the Fermi level, where emission processes dominate, this enhancement increases the rate of change in the electron distribution. In contrast, for the occupied states at or below the Fermi level, the rate decreases. In other words, the presence of non-thermal high-frequency phonons tends to reheat electrons, thereby suppressing the net energy transfer from electrons to phonons. This result is similar to the recently reported hot electron dynamics modulated by non-equilibrium phonon excitations in semiconductors[60]. As for gold, although non-thermal phonons also emerge during relaxation, the much weaker e-ph coupling strength limits the feedback to electrons, resulting in only minor deviations from the TTM behavior.

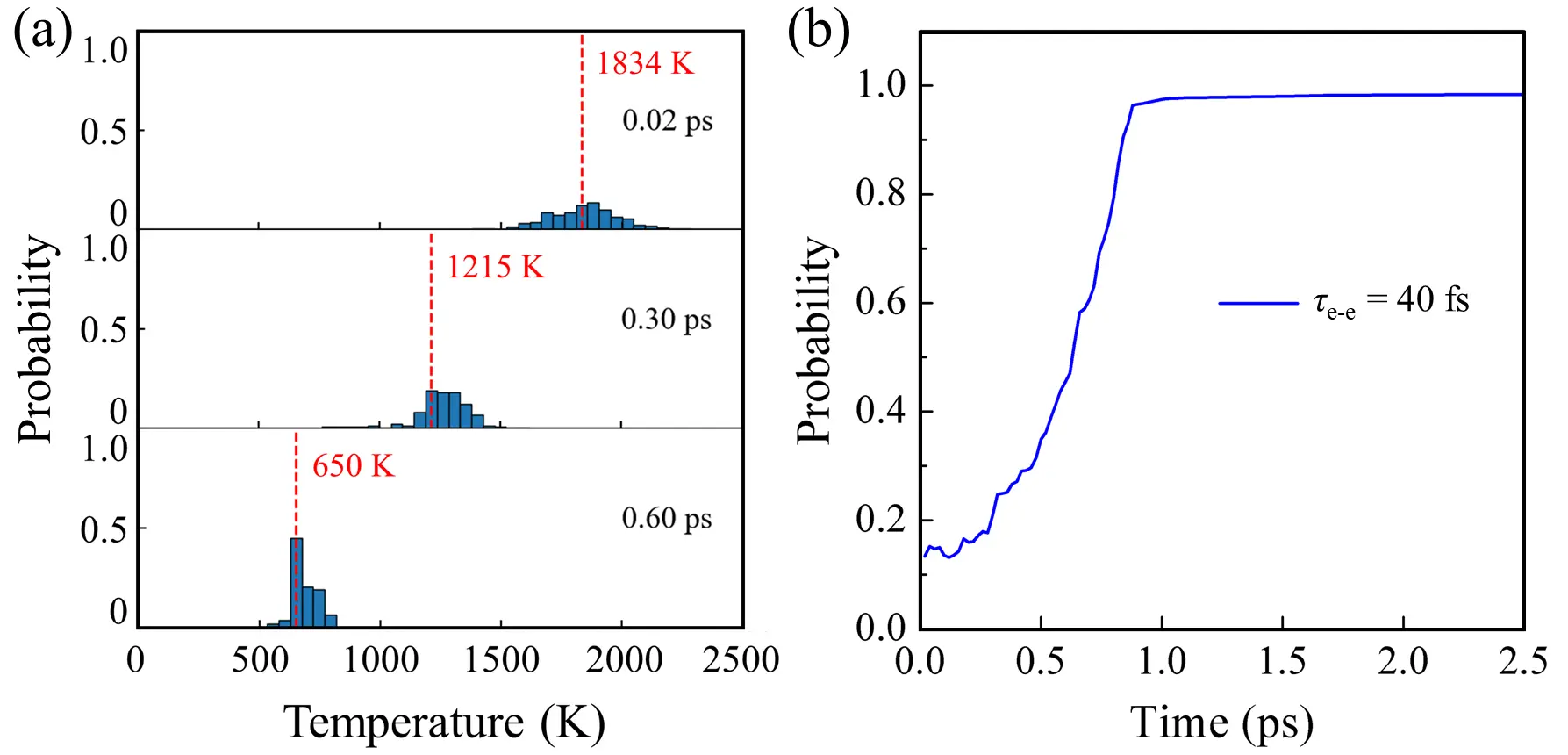

Finally, to further compare aluminum with gold and silver, Figure 9a shows the evolution of the distribution of Tmk. The broadening in aluminum is even more substantial than that in silver, and the probability remains below 0.3 for about 0.5 ps, corresponding to about half of the entire relaxation process (Figure 9b). This pronounced and long-lasting non-thermal electronic feature confirms that the assumption of a single electronic temperature, as adopted in the TTM, fails to capture the ultrafast relaxation dynamics in aluminum. Importantly, the deviation cannot be fully corrected by incorporating non-thermal phonons alone. Both electron and phonon non-equilibrium effects must be considered simultaneously. Our comparison across gold, silver, and aluminum demonstrates that the electron thermalization rate strongly affects the effective coupling constant. If electrons were assumed to thermalize instantaneously, the feedback from non-thermal phonons on Gep would be largely suppressed. Therefore, explicitly treating the interplay between non-thermal electrons and phonons is essential for accurately describing ultrafast energy relaxation.

Figure 9. (a) Effective temperature distribution of electronic states within ± 2 eV around the chemical potential at different times during τe-e = 40 fs relaxation in aluminum. The vertical axis represents the probability of electronic states falling within each 50 K temperature interval. The red dashed line indicates the current average temperature; (b) Time evolution of the probability that electronic states within ± 2 eV of the chemical potential fall within ± 25 K of the average temperature in aluminum, under the condition of τe-e = 40 fs.

4. Conclusion

In summary, we performed first-principles TDBE simulations that explicitly account for both non-equilibrium electrons and phonons, and compared the results with the TTM. We have demonstrated that the primary source of deviations from the TTM lies in the non-thermal electronic distribution and its thermalization dynamics, rather than in non-thermal phonons. In gold, the relaxation dynamics are well captured by the TTM, reflecting a rare case where the absence of strongly coupled scattering channels keeps the electronic distribution nearly thermalized. In silver, despite a coupling strength comparable to gold, pronounced deviations emerge once non-equilibrium electrons are included, revealing that specific e-ph scattering channels, not merely the overall coupling strength, govern the breakdown of the TTM. In aluminum, both non-equilibrium electrons and phonons strongly affect the relaxation process, rendering the TTM entirely invalid. These insights emphasize that explicitly accounting for electronic thermalization is essential for a reliable description of ultrafast relaxation processes. We further suggest that the electronic non-thermal distribution may be a central reason for the persistent discrepancies between theory and low-fluence pump-probe experiments, thereby pointing to a promising direction for future research.

Supplementary materials

The supplementary material for this article is available at: Supplementary materials.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Meng Lian, and Wen-Hao Mao for valuable discussions and helpful insights.

Authors contribution

Gui-Lin Zhu: Data analysis, conceptualization, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing.

Jing-Tao Lü: Supervision, methodology, resources, writing-review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

Jing-Tao Lü is an Editorial Board Member of Thermo-X. The other author declared that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The data and materials could be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.

Funding

This work is supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22273029).

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

References

-

1. Chen Z, Dong G, Qiu J. Ultrafast pump-probe spectroscopy—A powerful tool for tracking spin-quantum dynamics in metal halide perovskites. Adv Quantum Technol. 2021;4(8):2100052.[DOI]

-

2. Zhang Y, Dai J, Zhong X, Zhang D, Zhong G, Li J. Probing ultrafast dynamics of ferroelectrics by time-resolved pump-probe spectroscopy. Advanced Science. 2021;8(22):2102488.[DOI]

-

3. Danz T, Domröse T, Ropers C. Ultrafast nanoimaging of the order parameter in a structural phase transition. Science. 2021;371(6527):371-374.[DOI]

-

4. Ashoka A, Tamming RR, Girija AV, Bretscher H, Verma SD, Yang SD, et al. Extracting quantitative dielectric properties from pump-probe spectroscopy. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):1437.[DOI]

-

5. Glerean F, Rigoni EM, Jarc G, Mathengattil SY, Montanaro A, Giusti F, et al. Ultrafast pump-probe phase-randomized tomography. Light Sci Appl. 2025;14(1):115.[DOI]

-

6. Guo Z, Driver T, Beauvarlet S, Cesar D, Duris J, Franz PL, et al. Experimental demonstration of attosecond pump-probe spectroscopy with an X-ray free-electron laser. Nat Photon. 2024;18(7):691-697.[DOI]

-

7. Han GR, An MN, Jang H, Han NS, Kim JW, Jeong KS, et al. In situ and real-time ultrafast spectroscopy of photoinduced reactions in perovskite nanomaterials. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):4956.[DOI]

-

8. Swain AB, Kuttruff J, Vorberger J, Baum P. Stronger femtosecond excitation causes slower electron-phonon coupling in silicon. Phys Rev Research. 2025;7(2):023114.[DOI]

-

9. Guo CY, Zheng HT, Zhu GL, Huang YQ, Wang Q, Wu D, et al. Thermionic emission dynamics of ultrafast electron sources. Chin Phys Lett. 2025;42(5):057503.[DOI]

-

10. Sjakste J, Sen R, Vast N, Saint-Martin J, Ghanem M, Dollfus P, et al. Ultrafast dynamics of hot carriers: Theoretical approaches based on real-time propagation of carrier distributions. J Chem Phys. 2025;162(6):061002.[DOI]

-

11. Dürr HA, Ernstorfer R, Siwick BJ. Revealing momentum-dependent electron-phonon and phonon-phonon coupling in complex materials with ultrafast electron diffuse scattering. MRS Bull. 2021;46(8):731-737.[DOI]

-

12. He X, Ghosh M, Yang DS. Impacts of hot electron diffusion, electron-phonon coupling, and surface atoms on metal surface dynamics revealed by reflection ultrafast electron diffraction. J Chem Phys. 2024;160(22):224701.[DOI]

-

13. Mo M, Tamm A, Metsanurk E, Chen Z, Wang L, Frost M, et al. On the study of electron-phonon and phonon-phonon coupling in femtosecond laser-excited tungsten. In: Phipps CR, Gruzdev VE, editors. High-Power Laser Ablation VIII; 2024 Mar 2-Feb 26; New Mexico, United States; Bellingham: SPIE; 2024.[DOI]

-

14. Filippetto D, Musumeci P, Li RK, Siwick BJ, Otto MR, Centurion M, et al. Ultrafast electron diffraction: Visualizing dynamic states of matter. Rev Mod Phys. 2022;94(4):045004.[DOI]

-

15. Kaganov MI, Lifshitz IM, Tanatarov LV. Electron emission from metal surfaces exposed to ultrashort laser pulses. Sov Phys JETP. 1974;39(2):375-377. Available from: http://www.jetp.ras.ru/cgi-bin/dn/e_039_02_0375.pdf

-

16. Singh N. Two-temperature model of nonequilibrium electron relaxation: A review. Int J Mod Phys B. 2010;24(09):1141-1158.[DOI]

-

17. Singh N. Hot (non-equilibrium) electron relaxation: A review of the ultra-fast phenomena in metals and superconductors (PART I). arXiv:2410.19433 [Preprint]. 2024.[DOI]

-

18. Allen PB. Theory of thermal relaxation of electrons in metals. Phys Rev Lett. 1987;59(13):1460.[DOI]

-

19. Brorson SD, Kazeroonian A, Moodera JS, Face DW, Cheng TK, Ippen EP, et al. Femtosecond room-temperature measurement of the electron-phonon coupling constant γ in metallic superconductors. Phys Rev Lett. 1990;64(18):2172.[DOI]

-

20. Ritzmann U, Oppeneer PM, Maldonado P. Theory of out-of-equilibrium electron and phonon dynamics in metals after femtosecond laser excitation. Phys Rev B. 2020;102(21):214305.[DOI]

-

21. Kundu A, Ma J, Carrete J, Madsen GKH, Li W. Anomalously large lattice thermal conductivity in metallic tungsten carbide and its origin in the electronic structure. Mater Today Phys. 2020;13:100214.[DOI]

-

22. Li S, Wang A, Hu Y, Gu X, Tong Z, Bao H. Anomalous thermal transport in metallic transition-metal nitrides originated from strong electron-phonon interactions. Mater Today Phys. 2020;15:100256.[DOI]

-

23. Zhu GL, Shang MY, Lü JT. First-principles study on thermal and electrical transport properties of NbGe2 and NbSi2: The role of electron-phonon coupling. Chin Phys Lett. 2024;41(12):126301.[DOI]

-

24. Zhou ZZ, Yan YC, Yang XL, Xia Y, Wang GY, Lu X, et al. Anomalous lattice thermal conductivity driven by all-scale electron-phonon scattering in bulk semiconductors. Phys Rev B. 2023;107(19):195113.[DOI]

-

25. Yang X, Jena A, Meng F, Wen S, Ma J, Li X, et al. Indirect electron-phonon interaction leading to significant reduction of thermal conductivity in graphene. Mater Today Phys. 2021;18:100315.[DOI]

-

26. Zhou Z, Yang X, Fu H, Wang R, Lu X, Wang G, et al. Anomalous thermal transport driven by electron-phonon coupling in 2D semiconductor h-BP. Adv Funct Mater. 2022;32(45):2206974.[DOI]

-

27. Sun CK, Vallée F, Acioli L, Ippen EP, Fujimoto JG. Femtosecond investigation of electron thermalization in gold. Phys Rev B. 1993;48(16):12365.[DOI]

-

28. Groeneveld RHM, Sprik R, Lagendijk A. Femtosecond spectroscopy of electron-electron and electron-phonon energy relaxation in Ag and Au. Phys Rev B. 1995;51(17):11433.[DOI]

-

29. Del Fatti N, Voisin C, Achermann M, Tzortzakis S, Christofilos D, Vallée F. Nonequilibrium electron dynamics in noble metals. Phys Rev B. 2000;61(24):16956.[DOI]

-

30. Tong X, Bernardi M. Toward precise simulations of the coupled ultrafast dynamics of electrons and atomic vibrations in materials. Phys Rev Res. 2021;3(2):023072.[DOI]

-

31. Caruso F. Nonequilibrium lattice dynamics in monolayer MoS2. J Phys Chem Lett. 2021;12(6):1734-1740.[DOI]

-

32. Maldonado P, Carva K, Flammer M, Oppeneer PM. Theory of out-of-equilibrium ultrafast relaxation dynamics in metals. Phys Rev B. 2017;96(17):174439.[DOI]

-

33. Sadasivam S, Chan MKY, Darancet P. Theory of thermal relaxation of electrons in semiconductors. Phys Rev Lett. 2017;119(13):136602.[DOI]

-

34. Caruso F, Novko D. Ultrafast dynamics of electrons and phonons: From the two-temperature model to the time-dependent Boltzmann equation. Adv Phys X. 2022;7(1):2095925.[DOI]

-

35. Poncé S, Margine ER, Verdi C, Giustino F. EPW: Electron-phonon coupling, transport and superconducting properties using maximally localized Wannier functions. Comput Phys Commun. 2016;209:116-133.[DOI]

-

36. Li W, Carrete J, Katcho NA, Mingo N. ShengBTE: A solver of the Boltzmann transport equation for phonons. Comput Phys Commun. 2014;185(6):1747.[DOI]

-

37. Perdew JP, Burke K, Ernzerhof M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys Rev Lett. 1996;77(18):3865.[DOI]

-

38. Hamann DR. Optimized norm-conserving Vanderbilt pseudopotentials. Phys Rev B. 2013;88(8):085117.[DOI]

-

39. Giannozzi P, Baroni S, Bonini N, Calandra M, Car R, Cavazzoni C, et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: A modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J Phys Condens Matter. 2009;21(39):395502.[DOI]

-

40. Baroni S, de Gironcoli S, Dal Corso A, Giannozzi P. Phonons and related crystal properties from density-functional perturbation theory. Rev Mod Phys. 2001;73(2):515.[DOI]

-

41. Marzari N, Vanderbilt D. Maximally localized generalized Wannier functions for composite energy bands. Phys Rev B. 1997;56(20):12847.[DOI]

-

42. Souza I, Marzari N, Vanderbilt D. Maximally localized Wannier functions for entangled energy bands. Phys Rev B. 2001;65(3):035109.[DOI]

-

43. Kresse G, Furthmüller J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab-initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys Rev B. 1996;54(16):11169.[DOI]

-

44. Blöchl PE. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys Rev B. 1994;50(24):17953.[DOI]

-

45. Zenji A, Rampnoux JM, Grauby S, Dilhaire S. Ultimate-resolution thermal spectroscopy in time domain thermoreflectance (TDTR). J Appl Phys. 2020;128(6):065106.[DOI]

-

46. Hohlfeld J, Wellershoff SS, Güdde J, Conrad U, Jähnke V, Matthias E. Electron and lattice dynamics following optical excitation of metals. Chem Phys. 2000;251(1-3):237-258.[DOI]

-

47. Choi GM, Wilson RB, Cahill DG. Indirect heating of Pt by short-pulse laser irradiation of Au in a nanoscale Pt/Au bilayer. Phys Rev B. 2014;89(6):064307.[DOI]

-

48. Chen AM, Jiang YF, Sui LZ, Liu H, Jin MX, Ding DJ. Thermal analysis of double-layer metal films during femtosecond laser heating. J Opt. 2011;13(5):055503.[DOI]

-

49. Gray DE. American institute of physics handbook. 3rd ed. London: McGraw-Hill; 1972.

-

50. Li Y, Ji P. Ab initio calculation of electron temperature dependent electron heat capacity and electron-phonon coupling factor of noble metals. Comput Mater Sci. 2022;202:110959.[DOI]

-

51. Lin Z, Zhigilei LV, Celli V. Electron-phonon coupling and electron heat capacity of metals under conditions of strong electron-phonon nonequilibrium. Phys Rev B. 2008;77(7):075133.[DOI]

-

52. Chen Z, Curry CB, Zhang R, Treffert F, Stojanovic S, Toleikis S, et al. Ultrafast multi-cycle terahertz measurements of the electrical conductivity in strongly excited solids. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):1638.[DOI]

-

53. Hopkins PE, Kassebaum JL, Norris PM. Effects of electron scattering at metal-nonmetal interfaces on electron-phonon equilibration in gold films. J Appl Phys. 2009;105(2):023710.[DOI]

-

54. Mo MZ, Chen Z, Li RK, Dunning M, Witte BBL, Baldwin JK, et al. Heterogeneous to homogeneous melting transition visualized with ultrafast electron diffraction. Science. 2018;360(6396):1451-1455.[DOI]

-

55. Arefev MI, Shugaev MV, Zhigilei LV. Kinetics of laser-induced melting of thin gold film: How slow can it get? Sci Adv. 2022;8(38):eabo2621.[DOI]

-

56. Groeneveld R, Sprik R, Lagendijk A. Ultrafast relaxation of electrons probed by surface plasmons at a thin silver film. Phys Rev Lett. 1990;64(7):784.[DOI]

-

57. Jain A, McGaughey AJH. Thermal transport by phonons and electrons in aluminum, silver, and gold from first principles. Phys Rev B. 2016;93(8):081206.[DOI]

-

58. Hostetler JL, Smith AN, Czajkowsky DM, Norris PM. Measurement of the electron-phonon coupling factor dependence on film thickness and grain size in Au, Cr, and Al. Appl Opt. 1999;38(16):3614-3620.[DOI]

-

59. Waldecker L, Bertoni R, Ernstorfer R, Vorberger J. Electron-phonon coupling and energy flow in a simple metal beyond the two-temperature approximation. Phys Rev X. 2016;6(2):021003.[DOI]

-

60. Xu J, Li Weikang, Bao H. Hot Electron dynamics modulated by nonequilibrium phonon excitations. Ann Phys. 2025;537(10):e00126.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite