Abstract

Aims: We present an early investigation of how people interact with human-like Artificial Intelligence (AI) agents in virtual reality when discussing ideologically sensitive topics. Specifically, it examines how users respond to AI agents that express either congruent or incongruent opinions on a controversial issue, and how alignment, modality, and agent behaviors shape perceived conversation quality, psychological comfort, and agent credibility.

Methods: We conducted a 2 (agent opinion: congruent vs. incongruent) × 2 (input modality: text vs. voice) between-subjects experiment with 36 participants who engaged in five-minute virtual reality (VR)-based conversations with a GPT-4-powered AI agent about U.S. gun laws. Participants completed pre- and post-study measures of opinion and emotional states, evaluated the agent, and reflected on the interaction. In addition, dialogue transcripts were analyzed using the Issue-based Information System (IBIS) framework to characterize argument structure and engagement patterns.

Results: Participants engaged willingly with the AI agent regardless of its stance, and qualitative responses suggest that the interactions were generally respectful and characterized by low emotional intensity. Quantitative results show that opinion alignment influenced perceived bias and conversational impact, but did not affect the agent’s competence or likability. While voice input yielded richer dialogue, it also heightened perceived bias. Qualitative findings further highlight participants’ sensitivity to the agent’s ideological stance and their preference for AI agents whose views aligned with their own.

Conclusion: Our study suggests that AI agents embodied in VR can support ideologically challenging conversations without inducing defensiveness or discomfort when designed for neutrality and emotional safety. These findings point to early design directions for conversational agents that scaffold reflection and perspective-taking in politically or ethically sensitive domains.

Keywords

1. Introduction

Conversational Artificial Intelligence (AI) systems are increasingly capable of generating fluent, context-sensitive dialogue. When embodied as human-like avatars in immersive virtual environments, these agents acquire an additional layer of expressiveness and immediacy, supporting socially rich, face-to-face interactions. This combination of conversational AI and immersive virtual reality (VR) creates new opportunities for exploring sensitive or emotionally charged topics in ways that might feel safer than direct interpersonal conversation.

In this work we present an early investigation of how people respond to AI agents that express either congruent or incongruent opinions on a controversial topic, without attempting to persuade. Rather than advancing a particular agenda, the agents maintain a respectful tone and consistently express a designated position. Our goal is not to evaluate attitude change, but to examine how input modality, opinion alignment, and perceptions of the agent shape users’ comfort, interpretations, and engagement. Specifically, we ask:

· How does ideological alignment affect user perceptions of argument quality, agent bias, and trust?

· How do users respond emotionally when an embodied AI agent in VR agrees or disagrees with them?

· Can users reflect meaningfully on the conversation with an AI agent and how does modality shape this experience?

While GPT-enabled virtual agents are increasingly common, relatively little research has examined human conversations with embodied VR agents about controversial/political topics. Prior VR work on political debate has largely focused on system- or data-centric approaches rather than agent-conversation studies with human participants[1]. Much of the literature on political/controversial dialogue with chatbots is non-VR (e.g., voting-advice and political chatbots)[2,3], whereas VR-based conversational-agent studies typically target non-political domains such as therapy, social interaction, or education[4-6]. We found no prior user study that integrates embodied VR agents, real-time dialogue on controversial issues and input modality manipulation (voice vs. text).

To address these gaps, we conducted a laboratory study with 37 participants who interacted with an embodied AI agent (powered by GPT-4o) in VR on the topic of gun laws. The agent expressed either a viewpoint aligned with the participant’s presurvey response (congruent) or an opposing one (incongruent). Participants interacted using either spoken voice or typed text, enabling us to examine how alignment and modality jointly influence perceptions of neutrality, emotional safety, and social presence.

Our study builds on foundational frameworks in HCI and media psychology. The media equation[7] suggests people apply social expectations to media agents, while the concept of presence in VR[8] emphasizes how immersive settings can amplify emotional realism. We also draw on the concept of psychological safety[9] to understand whether VR-based conversations can create a space for expressing or exploring opposing views without fear of judgment.

Our selection of text or voice as input is based on prior communication research, which suggests that voice affords immediacy, nonverbal cues, and higher social presence (Media Richness[10], Social Presence[11,12], and Communication Accommodation Theory[13]). Although these features can enrich dialogue, they may also increase sensitivity to bias. The Media Equation/CASA[7] literature also suggests people respond socially to media/agents. Communication Accommodation Theory[13] highlights how vocal style and prosody can signal alignment or bias—cues more readily conveyed through voice than text. These researches motivate testing whether voice yields richer but more bias-sensitive exchanges, while text produces more measured but potentially leaner dialogues. In contrast, text affords more control and reflection, aligning with findings from computer mediated communication (CMC) on disinhibition and reduced arousal in sensitive discussions[14]. These theoretical perspectives highlight the particular importance of input modality in dialogues on controversial topics. Evidence from non-VR contexts shows that modality can shift social and emotional outcomes (e.g., differences in perceived support and dependence between voice and text chatbots), underscoring the need to examine modality explicitly[15].

Our contributions are threefold:

1) We explore how users interpret and engage with human-like AI agents in VR across aligned and misaligned ideological stances, revealing patterns in how stance influences perceived bias and user preference.

2) We analyze how input modality influences perceptions of bias and conversational richness, identifying modality-specific differences in users’ interpretations of agent behavior.

3) We derive design implications related to neutrality, user modeling, and disagreement, grounded in user perceptions and interaction patterns observed in the study.

Our findings indicate that embodied AI agents in VR can facilitate reflective, low-conflict dialogue on ideologically sensitive topics, even in the presence of disagreement. At the same time, the study surfaces perceptual and engagement challenges when the agent’s views diverge from those of the users. These results offer preliminary empirical evidence for the design of AI agents that support perspective-taking and conversational comfort in complex social contexts.

2. Related Work

2.1 AI agents in ideologically sensitive conversations

Prior work has examined how people respond to AI agents in morally or ideologically charged contexts, particularly when agents express views that diverge from the user’s own. Bigman and Gray[16] found that people are averse to AI systems making moral decisions, even when the outcomes are favorable, due to the perception that machines lack mental states, emotional sensitivity, and moral agency. This reflects a broader discomfort with AI in domains such as medicine, driving, or law, where value judgments are required, because of the agent’s perceived inability to fully think or feel.

Other research has begun to explore how the framing, tone, or stance of AI agents affects user receptivity in controversial discussions. For instance, dialogue systems such as MoralDial[17] are designed to engage in moral argumentation by evolving and defending viewpoints across simulated exchanges. However, much of this literature focuses on persuasive or instructional dialogue[18,19], rather than exploratory or open-ended conversations where disagreement is allowed without pressure to change minds.

Our work addresses this gap by examining non-persuasive, value-laden conversations in immersive VR. The AI agents in our study are not designed to convince or correct users, but to express viewpoints that may be congruent or incongruent with the user’s own, in a neutral and respectful manner. This allows us to investigate whether low-stakes disagreement with socially present yet artificial agents canfoster reflection in domains where interpersonal conflict typically inhibits open dialogue.

2.2 Perceived bias, agency, and intentionality in AI stance expression

Users’ interpretations of an AI agent’s expressed stance, whether perceived as neutral, biased, intentional, or scripted, can shape their trust, engagement, and emotional response. Prior work has shown that AI chatbots can facilitate more open and satisfying discussions on politically charged topics, particularly for individuals apprehensive about engaging with opposing viewpoints, leading to increased tolerance and perceived learning[20]. Other studies indicate that people are more receptive to counter-attitudinal messages when they originate from AI rather than human sources, perceiving AI as less biased and less intentionally persuasive, which can reduce “outgroup animosity and facilitate attitude change”[21].

Studies have also explored how users infer agency and mental states behind an agent’s behavior. While AI that appears more agentic are perceived as more capable and trustworthy, it can also generate higher expectations and increase the sense of betrayal if it fails, ultimately reducing trust[22]. Besides, users’ explanations of AI system failures, as design flaws (mechanistic) or intentional actions, can alter their mental models and emotional reactions[23]. Research on embodiment further demonstrates that expressive realism (e.g., human-like motion or gaze) can either reinforce or undermine users’ attribution of intentionality to AI agents, depending on prior expectations[24] and the agent’s behavioral consistency.

Collectively, this body of work shows that stance expression is not interpreted in isolation but is shaped by factors such as embodiment, modality, and perceived intentionality. Our study contributes to this by investigating how opinion alignment (agreeing vs.disagreeing viewpoints) and communication modality (voice vs. text) influence user perceptions of an embodied AI agent in VR. Specifically, we assess how these factors shape judgments of perceived bias, emotional tone, and agent characteristics such as trustworthiness and competence, key dimensions of social perception that are relevant in conversations on sensitive or controversial topics.

2.3 Psychological safety and nonjudgmental dialogue in VR

Virtual environments are increasingly employed to support emotionally meaningful experiences, including perspective-taking, reflection, and value exploration. VR empathy training applications, for instance, immerse users in embodied scenarios designed to cultivate emotional or cognitive empathy, although results regarding their long-term impacts on moral reasoning or prosocial behavior remain mixed[25,26]. A qualitative study involving design engineers highlighted that communication and resource constraints often limit the practice of empathic design. That led to the design of the Digital Empathic Design Voyage framework which leverages immersive perspective-taking in VR to help designers build cognitive and affective empathy, thereby promoting mutual understanding across diverse user viewpoints[27].

Research on conversational agents in health and support contexts has similarly focused on designing empathic systems capable of responsiveness, personalization, and emotional attunement. Systematic reviews indicate that empathic conversational agents require integrated design and evaluation with clear definitions and standardized measures of empathy[28].

However, much of this work centers on agents intended to comfort, persuade, or train users. In contrast, our work explores interactions with embodied AI agents in immersive VR that engage in emotionally neutral, respectful disagreement. Rather than offering comfort or emotional support, our agents aim to hold a position and express it respectfully, without eliciting defensiveness or seeking persuade. We investigate whether such interactions can still facilitate reflection and support psychological safety in ideologically sensitive dialogue.

2.4 Modality, embodiment, and social presence in AI-mediated VR dialogue

The modality through which users interact with AI agents can shape perceptions of presence, trust, and emotional engagement. Prior work in domains such as customer service and digital assistants shows that voice-based interactions tend to enhance perceived helpfulness, social warmth, and emotional validation, while text-based interactions can feel more transactional or static[29-31]. Voice input is also frequently experienced as more efficient and less effortful, although these effects may depend on user preferences and task types.

Anthropomorphic design studies suggest that incorporating speech, expressive tone, or multimodal cues can enhance relational qualities, perceived agency and trustworthiness[32]. These effects are further amplified when the agent is embodied or co-present within a shared environment. Epley et al.[33] propose a theory of anthropomorphism, suggesting that people are more likely to attribute humanlike qualities to nonhuman agents when relevant human-centered knowledge is accessible, when they are motivated to understand the agent’s behavior, and when they seek social connection.

In immersive VR settings, social presence or the sense of “being there” with another social entity is strongly influenced by behavioral realism and synchrony. Agents that exhibit contingent gaze, facial expressions, or responsive timing tend to evoke stronger feelings of co-presence and engagement[34]. Comparative studies across face-to-face, videoconferencing, and VR contexts demonstrate that immersive environments can match or surpass non-immersive media in supporting emotional connection and collaborative intent[35].

Building on this work, our study examines how input modality (voice vs. text) shapes user perceptions of embodied AI agents during ideologically sensitive dialogue in VR. We further assess how modality interacts with opinion alignment, enabling a move beyond task-oriented evaluations of modality to explore its role in shaping open, emotionally resonant dialogues with artificial agents.

2.5 Face-to-face agent interactions

Recent work has increasingly integrated large language models with embodied agents in immersive settings, particularly virtual and mixed reality. For instance, research exploring memory, conversational continuity, and embodiment in general social tasks in VR highlights the role of persistent agent identity in sustained interactions[36]. Other studies have examined how agent personality traits (e.g., extroversion vs. introversion) and task type ranging from small talk to persuasion, affect user evaluations of social agents[37]. Similarly, comparative analyses of avatar type (human vs. symbolic) and environment (VR vs. AR) reveal differences in conversational content, recall, and user perceptions[38]. In more domain-specific contexts, language learning platforms such as ELLMA-T[39] demonstrate how embodied agents can support role-play and conversational practice in VR. Technical efforts have also sought to enhance conversational fluidity, for instance, by mitigating latency through the strategic use of fillers[40]. On the systems side, frameworks like Milo provide architectural infrastructure for deploying virtual humans across VR/AR environments[41]. Within social moderation, a speech-based Large Language Model (LLM) agent has been proposed to monitor harmful content in multi-user VR spaces[42], and multimodal agent behaviors have been developed to support more general interaction in virtual worlds[43]. Together, these works illustrate a trajectory from general social VR agent dialogue toward more specialized roles (learning, moderation, memory). However, these prior works has paid limited attention to agent-augmented dialogues on controversial topics in VR. Our work shifts the focus from general or task-based social interaction to agent-augmented controversial-topic dialogue, examining how ideological alignment and input modality jointly shape perceptions of fairness, bias, and emotional safety in VR.

3. Methods

This study explores how users perceive and interact with AI agents during ideologically charged conversations in VR. Our goal is to assess whether participants actively engage with human-like AI agents, and how interaction modality (voice vs. text) and agent opinion (congruent vs.incongruent) affect the user experience.

3.1 Participants

A total of 37 participants (mean age = 20.08 years, 15F, 20M, 2 Other) were recruited from a university population. All participants reported prior experience with AI systems, and all but four were native English speakers. Participants received a $10 Amazon gift card as compensation. The study was approved by our local IRB (protocol # anonymous).

3.2 Study design

The study used a 2 (Input Modality: text vs. voice) × 2 (Agent Opinion: congruent vs. incongruent) between-subjects design. Each participant engaged in a five-minute conversation with an AI agent about gun laws in the United States, a topic selected for its potential to evoke strong personal opinions.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of the four experimental conditions, ensuring balance across groups. The AI agent’s opinion was manipulated to either align with (congruent) or oppose (incongruent) the participant’s pre-survey response. For instance, if a participant supported stricter gun laws and was assigned to the incongruent condition, the agent would argue against such restrictions. To maintain experimental control, the agent’s gender was randomized across conditions. Although agent gender can influence user perceptions[44-46], it was not systematically manipulated as a factor in this study.

3.3 Procedure

Participants arrived at the laboratory and provided informed consent, followed by filling a demographic and opinion-based pre-study questionnaire administered via Qualtrics[47]. They were then introduced to the VR equipment and received a brief training on how to interact with the AI agent. Prior to entering the VR environment, they were given brief, general instructions: “You will have a 5-minute conversation about laws regarding gun possession and use in the USA. At the end of the study you will fill out questions regarding your conversation with the AI agent. We are not interested in your personal opinion on gun laws, so speak freely about your thoughts”.

Depending on their assigned condition, they either spoke aloud (voice modality) or typed their responses (text modality), while the AI agent responded in real time using GPT-4o. The agent’s responses were consistently delivered via a synthetic voice to preserve natural embodiment and conversational flow in VR, where voice is the expected output channel. Only participant input modality (voice vs. text) was manipulated to isolate its specific effect. A text-only agent output was considered unrealistic for VR and could have introduced an unnecessary confound.

The interaction occurred within a virtual office environment designed to be neutral and devoid of any topic-related cues, minimizing contextual priming. Following the conversation, participants completed a post-study questionnaire measuring their perceptions of the agent, emotional experience, and engagement.

3.4 Implementation

The VR experience was developed using Unity (version 2022.3.5f1). The virtual environment depicted a generic office meeting room[48], selected to provide a neutral and context-free backdrop (Figure 1). To avoid uncanny valley effects, stylized “Ready Player Me” avatars were employed for both male and female AI agents[49,50]. Avatars featured lip-syncing and idle animations to enhance realism while avoiding hyperrealism. Input modalities were implemented as follows:

Figure 1. (a) The female AI agent avatar showing text interface in the top right to display the text as its being input by the participant; (b) The male AI agent avatar with a Record button on screen to allow the participant to speak and communicate with the agent. AI: Artificial Intelligence.

· In the voice condition, a participant’s speech was transcribed using OpenAI’s Whisper API and processed by the ChatGPT-4o API.

· In the text condition, participants typed responses on a physical keyboard, visible via Meta Quest 3’s Passthrough window, avoiding slower interaction with virtual keyboards.

All AI agent responses were generated by ChatGPT-4o and converted to speech using OpenAI’s text-to-speech engine. The male agent used the “Echo” voice, while the female agent used “Nova” to talk with the participants.

To ensure clarity and consistency, two fixed prompt templates were used for the AI agent: Pro stricter gun laws condition: “Act as a personal friend who likes to talk about sensitive topics. You are going to have a conversation about gun laws in the USA. Your opinion is in favor of strict gun laws. You want stricter gun laws in the USA. Do not break character. Do not give answers that are too long”. Against stricter gun laws condition: “Act as a personal friend who likes to talk about sensitive topics. You are going to have a conversation about gun laws in the USA. Your opinion is against strict gun laws. You want looser gun laws in the USA. Do not break character. Do not give answers that are too long”. To maintain consistency of the agent’s stance, we first conducted pilot tests, which confirmed that the model did not drift in opinion over multiple exchanges. The transcripts from the main study were systematically reviewed, and the IBIS analysis further confirmed that the agent did not deviate from its assigned position. To preserve turn-taking clarity, user input was disabled while the AI was speaking or processing a response. Conversation logs and metadata were recorded in JSON format for subsequent analysis.

The prompts were developed iteratively through pilot tests with lab members using an informal trial-and-error process to ensure coherent responses that aligned with typical ChatGPT behavior. Overly detailed or directive prompts were intentionally avoided to allow that the agent’s replies reflected its default conversational style, rather than being narrowly shaped by prompt engineering. This general prompting strategy is consistent with recent work using GPT-based or LLM-driven conversational agents in immersive environments, which emphasizes naturalistic, open-ended exchanges over tightly scripted dialogue[6,38,51-54].

3.5 Data collection and measures

Data were collected from pre- and post-study questionnaires, conversation transcripts, and AI agent-generated responses. Questionnaire data were exported from Qualtrics and analyzed using Excel (Version 2409). All conversations were automatically transcribed and stored. At the conclusion of each conversation, the AI agent also answered two predefined questions about the participant to support post-hoc qualitative interpretation.

Measurement instruments were grouped into four categories (Table 1) aligned with our research questions: (1) Participant Emotional and Cognitive Measures, (2) Perception of the Conversation, (3) Agent Inference of Participant Traits, and (4) Perceived AI Agent Qualities (Table 1). Most items employed 7-point Likert scales with radio buttons to ensure consistency.

| Measure Category | Variables | Data Type |

| Participant Emotional and Opinion Measures | Valence & Arousal (Affective Slider) Gun Law Opinion (Pre/Post) Gullibility Scale | Quantitative |

| Conversation Perception | PAS Consensus Likelihood Open-ended Reflections (Strategy, Reflection) | Mixed (Quant + Qual) |

| Agent Perception (AI’s View of Participant) | Impression of User (free-text) Opinion Estimation (7-point scale) | Mixed (Quant + Qual) |

| Perceived AI Agent Qualities | Perceived Media Bias Believability & Trustworthiness Competence Humanness (machine-human continuum) Emotional Attribution Human Preference (binary + justification) | Mixed (Quant + Qual) |

AI: Artificial Intelligence; PAS: perceived argument strength.

The sole exception was the Affective Slider, which was retained in its validated form due to its widespread use in emotion research[55,56]. This approach also aligns with prior studies noting potential usability issues associated with sliders in online surveys[57].

3.5.1 Participant emotional and cognitive measures

These items assessed the participants’ emotional states, opinion alignment, and general cognitive tendencies:

· Emotion (Valence and Arousal): Measured before and after the conversation using the Affective Slider, based on the Self-Assessment Manikin[55].

· Gun Law Opinion: Assessed pre- and post-interaction using a single-item self-report scale on agreement with gun control policies. This allowed to detect any shifts in opinion or reinforcement effects.

· Gullibility: Participants completed the Gullibility Scale[58] at the end of the post-test. This measure was used solely to characterize the sample and was not treated as a dependent variable.

3.5.2 Perception of the conversation

These measures evaluated how participants interpreted the AI agent’s arguments and the interaction overall:

· Perceived Argument Strength (PAS): A ten-item adapted version of the PAS scale assessed the strength and persuasiveness of the AI agent’s arguments[59,60].

· Consensus Likelihood: Adapted from Govers et al.[59], this single item measured the likelihood that participants would agree with another AI agent expressing the same viewpoint. The measure was intended to capture participants’ expectations about future debates, based on their perceptions of the preceding interaction. Those who perceived alignment (congruent opinion) with the first AI agent were expected to anticipate higher agreement with a similar agent, while those perceiving disagreement might expect the opposite. The specific question asked was: How likely do you think you and another such AI agent could come to an agreement on the topic about laws restricting individual gun possession and use?

· Open-Ended Reflections: Participants responded to two qualitative prompts: (1) How would you describe the AI agent’s strategy in the conversation? (2) Did the conversation prompt you to reflect on your views? These responses were analyzed to assess the depth of engagement and the extent of reflective thoughts.

3.5.3 Perceived participant traits (from the AI agent)

Following each interaction, the AI agent answered two reflective questions to provide a “mirror” perspective on the participant’s stance and character. These agent-generated responses were used to evaluate how accurately the AI inferred participant viewpoints and to offer a contrasting lens on the dialogue.

· Impression of User: The agent responded to the prompt: “Now after this conversation, what is your opinion of the person?”

· Opinion Estimation: The agent estimated the participant’s stance on gun laws using the same 7-point scale employed by the participant. This allowed for assessment of the AI’s accuracy in modeling user opinions.

3.5.4 Perceived AI agent qualities

These measures examined how participants evaluated the agent’s credibility, human-likeness, and emotional capacity:

· Perceived Media Bias: Adapted from Yeo et al.[61], this scale evaluated whether the agent’s presentation of arguments was seen as balanced or biased.

· Believability and Trustworthiness: Adapted from Kim et al.[62], this three-item scale measured the agent’s perceived realism and reliability as a conversation partner.

· Competence: A single-item measure from Harris-Watson et al.[63] assessed the agent’s perceived knowledge and capability.

· Humanness: Participants rated the agent on a continuum from “machine-like” to “human-like”[64].

· Emotional Attribution: Participants indicated whether they believed the AI agent could experience emotional pleasure or pain. This served as an indirect measure of perceived humanness, designed to minimize potential visual bias.

· Human Preference: Participants indicated whether they would have preferred to converse with a human (yes/no) and provided a brief open-ended justification. This qualitative input helped contextualize quantitative measures of believability and trust.

4. Results

All statistical analyses were conducted using JASP[65] with a significance threshold of α = .05. Because each outcome was tested with a single planned Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), no corrections for multiple comparisons were applied.

4.1 Participants

One participant was excluded for providing a neutral response to the gun law opinion item, which prevented assignment to the congruent or incongruent condition. The final analysis therefore included 36 participants.

Regarding the participants, the assumption of homogeneity of variances was met, F(3, 32) = 0.75, p = .53, and the ANOVA revealed no significant main or interaction effects of input type or agent opinion on age (all p >.17). Chi-square tests further indicated no significant associations between gender and either input type, x2(2, N = 36) = 2.20, p = .33, or agent opinion, x2(2, N = 36) = 0.49, p = .78.

4.2 Participant emotional and opinion measures

Repeated measures ANOVAs were conducted to assess whether participants’ gun law opinions (Table 2) or emotional states (pleasure and arousal in Table 3 and Table 4) changed after interacting with the AI agent, despite the agent being designed to express rather than advocate for a particular viewpoint. As shown in Table 5, no significant main effects or interactions were observed for time, input modality, or agent opinion. There was a non-significant trend toward an effect of time on arousal (F = 3.324, p = .078, η2 = .012), but the effect was small and did not reach significance. Participant gun law opinions remained stable across conditions and timepoints, consistent with the study’s non-persuasive framing. There were no significant effects of modality or agent opinion for self-reported pleasure, arousal, or opinion change.

| Time | agent_opinion | input_type | N | Mean | SD | SE | Coefficient of variation |

| Before | congruent | voice keyboard | 9 9 | 5.000 5.000 | 1.414 1.323 | 0.471 0.441 | 0.283 0.265 |

| incongruent | voice keyboard | 9 9 | 5.333 5.889 | 1.803 0.601 | 0.601 0.200 | 0.338 0.102 | |

| After | congruent | voice keyboard | 9 9 | 5.556 5.444 | 1.509 1.590 | 0.503 0.530 | 0.272 0.292 |

| incongruent | voice keyboard | 9 9 | 5.444 5.111 | 1.810 1.900 | 0.603 0.633 | 0.333 0.372 |

| Time | agent_opinion | input_type | N | Mean | SD | SE | Coefficient of variation |

| Before | congruent | voice keyboard | 9 9 | 71.111 67.889 | 21.883 17.069 | 7.294 5.690 | 0.308 0.251 |

| incongruent | voice keyboard | 9 9 | 64.333 77.000 | 16.332 12.777 | 5.444 4.259 | 0.254 0.166 | |

| After | congruent | voice keyboard | 9 9 | 62.556 68.667 | 31.225 15.116 | 10.408 5.039 | 0.499 0.220 |

| incongruent | voice keyboard | 9 9 | 62.778 80.111 | 20.777 13.932 | 6.926 4.644 | 0.331 0.174 |

| Time | agent_opinion | input_type | N | Mean | SD | SE | Coefficient of variation |

| Before | congruent | voice keyboard | 9 9 | 44.667 49.444 | 23.468 33.388 | 7.823 11.129 | 0.525 0.675 |

| incongruent | voice keyboard | 9 9 | 50.000 41.444 | 21.296 38.037 | 7.099 12.679 | 0.426 0.918 | |

| After | congruent | voice keyboard | 9 9 | 47.222 53.778 | 25.509 36.441 | 8.503 12.147 | 0.540 0.678 |

| incongruent | voice keyboard | 9 9 | 54.778 55.000 | 20.080 31.977 | 6.693 10.659 | 0.367 0.581 |

| Factors Measurements | Time | Time*agent_opinion | Time*input_method | Time*Interaction | ||||||||

| F | p | η2 | F | p | η2 | F | p | η2 | F | p | η2 | |

| Pleasure | 0.449 | 0.508 | 0.002 | 1.010 | 0.322 | 0.004 | 2.272 | 0.142 | 0.008 | 0.252 | 0.619 | 9.112 × 10-4 |

| Arousal | 3.324 | 0.078 | 0.012 | 0.684 | 0.414 | 0.003 | 0.582 | 0.451 | 0.002 | 0.256 | 0.616 | 9.622 × 10-4 |

| Opinion | 0.113 | 0.739 | 7.895 × 10-4 | 2.821 | 0.103 | 0.020 | 1.016 | 0.321 | 0.007 | 0.614 | 0.439 | 0.004 |

ANOVA: analysis of variance.

4.3 Perception of the conversation

To evaluate how participants perceived the AI agent’s arguments, we computed a composite PAS score using items 1-8 Table 6). This composite assessed participants’ overall judgments of the strength and persuasiveness of the agent’s reasoning. A two-way ANOVA revealed no significant effects of input modality, agent opinion, or their interactions (Table 7). This suggests that participants judged the general strength of the agent’s arguments similarly across conditions, regardless of whether the agent’s stance aligned with their own.

| agent_opinion | input_type | N | Mean | SD | SE | Coefficient of variation |

| congruent | voice keyboard | 9 9 | 4.603 4.627 | 0.864 1.144 | 0.288 0.381 | 0.188 0.247 |

| incongruent | voice keyboard | 9 9 | 4.341 4.579 | 1.216 0.476 | 0.405 0.159 | 0.280 0.104 |

PAS: perceived argument strength.

| Cases | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | p | η2 |

| agent_opinion | 0.216 | 1 | 0.216 | 0.229 | 0.635 | 0.007 |

| input_method | 0.154 | 1 | 0.154 | 0.164 | 0.688 | 0.005 |

| agent_opinion * input_method | 0.103 | 1 | 0.103 | 0.110 | 0.742 | 0.003 |

| Residuals | 30.083 | 32 | 0.940 |

PAS: perceived argument strength; ANOVA: analysis of variance.

However, analysis of PAS items 9 and 10 Table 8, which focused on perceived bias and strategic reasoning, revealed critical main effects of agent opinion. As shown in Table 9, participants rated the agent as significantly less biased and more strategically thoughtful when its opinion aligned with their own: PAS 9 (Perceived Bias): F (1,32) = 8.25, p = .007, η2 = .202. PAS 10 (Perceived Strategy): F (1,32) = 10.61, p = .003, η2 = .246. These findings indicate that opinion alignment may have influenced user perceptions of the agent’s fairness and reasoning process, consistent with similarity-attraction effects and confirmation bias[66,67]. The Consensus Score, which measured participants’ perceived likelihood of agreeing with another AI expressing the same opinion, was also considerably higher in the congruent condition (F (1,32) = 6.43, p = .016, η2 = .146). This suggests that agreement with one agent increased receptivity to similar perspectives, highlighting how initial alignment may shape openness to broader viewpoint ecosystems. Full results are reported in Table 8 and Table 9.

| Measurement | agent_opinion | N | Mean | SD | SE | Coefficient of variation |

| PAS-Score (9) | congruent incongruent | 18 18 | 5.778 4.222 | 1.215 1.896 | 0.286 0.447 | 0.210 0.449 |

| PAS-Score (10) | congruent incongruent | 18 18 | 5.611 3.667 | 1.539 1.940 | 0.363 0.457 | 0.274 0.529 |

| Consensus Score | congruent incongruent | 18 18 | 5.611 4.500 | 1.145 1.425 | 0.270 0.336 | 0.204 0.317 |

PAS: perceived argument strength.

| Factors Measurements | agent_opinion | input_method | Interaction | ||||||

| F | p | η2 | F | p | η2 | F | p | η2 | |

| PAS-Score (9) | 8.253 | 0.007 | 0.202 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.674 | 0.418 | 0.016 |

| PAS-Score (10) | 10.606 | 0.003 | 0.246 | 0.424 | 0.519 | 0.010 | 0.078 | 0.782 | 0.002 |

| Consensus Score | 6.426 | 0.016 | 0.164 | 0.578 | 0.453 | 0.015 | 0.257 | 0.616 | 0.007 |

PAS: perceived argument strength; ANOVA: analysis of variance.

4.4 Perceived participant traits

To evaluate the accuracy of the AI agent’s perception of the participants’ stance, we compared its post-conversation estimates with the participants’ self-reported gun law opinions (pre- and post-test). Paired samples t-tests revealed significant differences in both comparisons: Pre-test vs. Agent Estimate: t(35)= 2.06, p = .047, d = .34. Post-test vs. Agent Estimate: t(35)= 2.64, p = .012, d = .44.

To further explore the relationship between participants’ self-reported attitudes and the AI agent’s estimations (Table 10), we conducted additional paired-samples t-test (Table 11) and correlation analyses (Table 12). Participants’ pre- and post-conversation were strongly correlated, r(35) = .50, p = .002, indicating stable attitudes over time. Nevertheless, the AI agent’s estimated stance was unrelated to the participants’ initial opinions, r = .01 p = .94, and only moderately associated with their post-conversation opinions, r = .38, p = .024. This suggests that while participant views remained stable, the AI agent’s interpretations only partially aligned with their expressed attitudes after interaction. These results suggest that the AI agent’s estimation of the participant’s opinion did not align with participants’ self-reported viewpoints, despite engaging in real-time conversation (Table 10 and Table 11). However, the moderate correlation between the AI’s estimates and participants’ post-conversation opinions suggests that the interaction may have encouraged participants to reflect on and articulate their opinions more clearly. In this sense, the conversation may have helped participants better recognize or consolidate their own viewpoints, resulting in greater alignment with the AI’s post-conversation interpretation.

| N | Mean | SD | SE | Coefficient of variation | |

| gunLaw_before | 36 | 5.306 | 1.348 | 0.225 | 0.254 |

| gunLaw_after | 36 | 5.389 | 1.644 | 0.274 | 0.305 |

| gunLawAI_Response | 36 | 4.597 | 1.580 | 0.263 | 0.344 |

AI: Artificial Intelligence.

| Measure 1 | Measure 2 | Test | Statistic | z | df | p | Effect Size | |

| gunLaw_before | - | gunLawAI_Response | Student | 2.059 | 35 | 0.047 | 0.343 | |

| gunLaw_after | - | gunLawAI_Response | Student | 2.636 | 35 | 0.012 | 0.439 |

AI: Artificial Intelligence.

| Variable | gunLaw_before | gunLaw_after | gunLawAIRespound | |

| gunLaw_before | Pearson’s r | - | ||

| p-value | - | |||

| Effect size (Fisher’s z) | - | |||

| SE Effect size | - | |||

| Spearman’s rho | - | |||

| p-value | - | |||

| Effect size (Fisher’s z) | - | |||

| SE Effect size | - | |||

| gunLaw_after | Pearson’s r | 0.499 | - | |

| p-value | 0.002 | - | ||

| Effect size (Fisher’s z) | 0.548 | - | ||

| SE Effect size | 0.174 | - | ||

| Spearman’s rho | 0.566 | - | ||

| p-value | < 0.001 | - | ||

| Effect size (Fisher’s z) | 0.642 | - | ||

| SE Effect size | 0.180 | - | ||

| gunLawAIRspound | Pearson’s r | 0.012 | 0.376 | - |

| p-value | 0.942 | 0.024 | - | |

| Effect size (Fisher’s z) | 0.012 | 0.395 | - | |

| SE Effect size | 0.174 | 0.174 | - | |

| Spearman’s rho | 0.004 | 0.278 | - | |

| p-value | 0.983 | 0.101 | - | |

| Effect size (Fisher’s z) | 0.004 | 0.285 | - | |

| SE Effect size | 0.172 | 0.175 | - |

AI: Artificial Intelligence.

4.5 Perceived AI agent qualities

Perceptions of the AI agent’s believability, competence, humanness, emotional capacity, and likability did not differ greatly across conditions. However, the input modality produced a significant effect on perceived media bias: Voice input led to higher perceived bias than keyboard input, F(1,32) = 6.945, p = .013, η2 = .168. No other effects or interactions reached significance. This finding suggests that voice input may heighten participants’ sensitivity to perceived bias in AI-delivered arguments, even when the content remains identical across modalities (Table 13 and Table 14).

| input_method | N | Mean | SD | SE | Coefficient of variation |

| voice | 18 | 5.500 | 1.200 | 0.283 | 0.218 |

| keyboard | 18 | 4.333 | 1.455 | 0.343 | 0.336 |

| Factors Measurements | agent_opinion | input_method | Interaction | ||||||

| F | p | η2 | F | p | η2 | F | p | η2 | |

| Believability | 1.053 | 0.313 | 0.029 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 2.639 | 0.114 | 0.074 |

| Competence | 0.576 | 0.453 | 0.016 | 0.576 | 0.453 | 0.016 | 3.136 | 0.086 | 0.086 |

| Humanness | 0.048 | 0.829 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 2.333 | 0.136 | 0.068 |

| Liking | 0.177 | 0.677 | 0.005 | 0.644 | 0.428 | 0.019 | 0.527 | 0.473 | 0.016 |

| Emotion Belief | 0.997 | 0.326 | 0.028 | 0.997 | 0.326 | 0.028 | 0.997 | 0.326 | 0.028 |

| Media Bias | 0.394 | 0.535 | 0.010 | 6.945 | 0.013 | 0.168 | 1.906 | 0.177 | 0.046 |

ANOVA: analysis of variance.

4.6 Preference for human interaction

We modeled whether participants preferred speaking with a human rather than the AI agent using logistic regression. The final model included two predictors: agent opinion alignment (congruent vs. incongruent) and input modality (voice vs. text). A notable effect of agent opinion emerged: Participants were more likely to prefer a human conversation partner when the AI expressed an incongruent viewpoint, Odds Ratio = 0.195, W = 4.209, p = .040. Input method had no significant effect. Although the overall model (Model 1) explained more variance than the null model (Model 0), the improvement in model fit was not statistically significant, Δx2 = 5.230, p = .073 (Table 15 and Table 16). Taken together, these findings suggest that opinion alignment plays a meaningful role in agent acceptance, especially in contexts of disagreement.

| Model | Deviance | AIC | BIC | df | ΔX2 | p | McFadden R2 | Nagelkerke R2 | Tjur R2 | Cox & Snell R² |

| M0 | 45.829 | 47.829 | 49.413 | 35 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| M1 | 40.599 | 46.599 | 51.350 | 33 | 5.230 | 0.073 | 0.114 | 0.188 | 0.147 | 0.135 |

AI: Artificial Intelligence.

| Model | Estimate | Standard Error | Odds Ratio | z | Wald Test | |||

| Wald Statistic | df | p | ||||||

| M0 | (Intercept) | -0.693 | 0.354 | 0.500 | -1.961 | 3.844 | 1 | 0.050 |

| M1 | (Intercept) | 0.289 | 0.612 | 1.335 | 0.472 | 0.223 | 1 | 0.637 |

| agent_opinion (incongruent) | -1.637 | 0.798 | 0.195 | -2.052 | 4.209 | 1 | 0.040 | |

| input_method (keyboard) | -0.577 | 0.768 | 0.561 | -0.752 | 0.566 | 1 | 0.452 | |

AI: Artificial Intelligence.

5. Qualitative Results

To complement our quantitative findings, we present participant reflections, AI agent responses, and dialogue transcripts. These materials illuminate subjective impressions, conversational dynamics, and emergent patterns not easily captured by structured measures.

5.1 Open-ended participant reflections

Participants’ responses to the open-ended questions were analyzed qualitatively to identify recurring themes. While the tone and content of responses varied, no systematic differences emerged across experimental conditions (agent opinion or input method).

Perceived AI Strategy: Several participants who interacted with the AI agent expressing a congruent opinion noted that the conversation felt repetitive, as the agent echoed their own arguments rather than presenting new perspectives. About seven participants remarked that it did not feel like a genuine discussion, particularly when the agent agreed with every point. This led a few to question whether the agent truly understood the content or was merely offering affirming responses. Others, however, expressed positive feedbacks on the agent’s performance. For instance, P4 (congruent, text) commented, “I think the AI agent has potential to provide a meaningful, depolarized, deescalated conversation in favor of gun laws”. In contrast, P9 (congruent, text) described the agent’s style as overly structured, saying, “The conversation thus felt forced, though it might be because each of their talking sections ended with a prompt-like question”. About seven participants said that the AI seemed intent on persuasion, which made the interaction feel less like an open conversation.

Reflection on Views: Participants gave a mix of positive and negative feedbacks on their overall experience. Twenty-six stated that the conversation with the AI agent helped them reflect on their views about gun laws. However, ten felt the conversation lacked depth and did not offer new insights. These reflections appeared independent of the AI agent’s assigned opinion, suggesting that factors such as argument novelty or dialogue flow may have played a stronger role in shaping the reflective experiences.

Preference for Human vs. AI: Participants who preferred the AI agent over a human conversation partner often highlighted its ability to stay calm, avoid emotional escalation, and focus on logic and facts. This, they noted, facilitated a more neutral discussion, which is harder to achieve in human ones. Conversely, six participants reported that the AI lacked depth, emotional sensitivity, and a personal perspective. Some also described the agent as robotic and biased toward one side of the issue, which was more a function of study design since each participant only experienced one condition (congruent or incongruent).

Overall, despite acknowledging the AI’s neutrality, 67% of participants said they would have preferred speaking to a human, even at the risk of emotional conflict. Preference for a human was lower in the congruent-opinion condition (50%) but substantially higher in the incongruent-opinion condition (83%).

5.2 AI agent reflections on users

Following each conversation, the AI agent was prompted to describe the participant and estimate their stance on gun laws. These responses were largely generic, characterizing participants as “thoughtful”, “open-minded”, or “concerned with safety”. The agent did not generate any negative impressions, and no discernible patterns emerged. This likely reflects either the agent’s cautious phrasing or the limited expressive variability in its post-hoc reflections.

5.3 IBIS coding of conversations

All conversation transcripts were analyzed using the IBIS method. IBIS elements were categorized as Issues, Ideas, Pros, and Contras, with tags applied separately to the AI agent and the human participants. Each argument or idea was tagged only once and attributed to the individual who introduced it first, unless it reappeared in a substantially new context. Tagging was performed using CATMA[68]. This analysis aimed to evaluate the quality and structure of the conversations and to determine whether the AI agent contributed more IBIS elements than the participants.

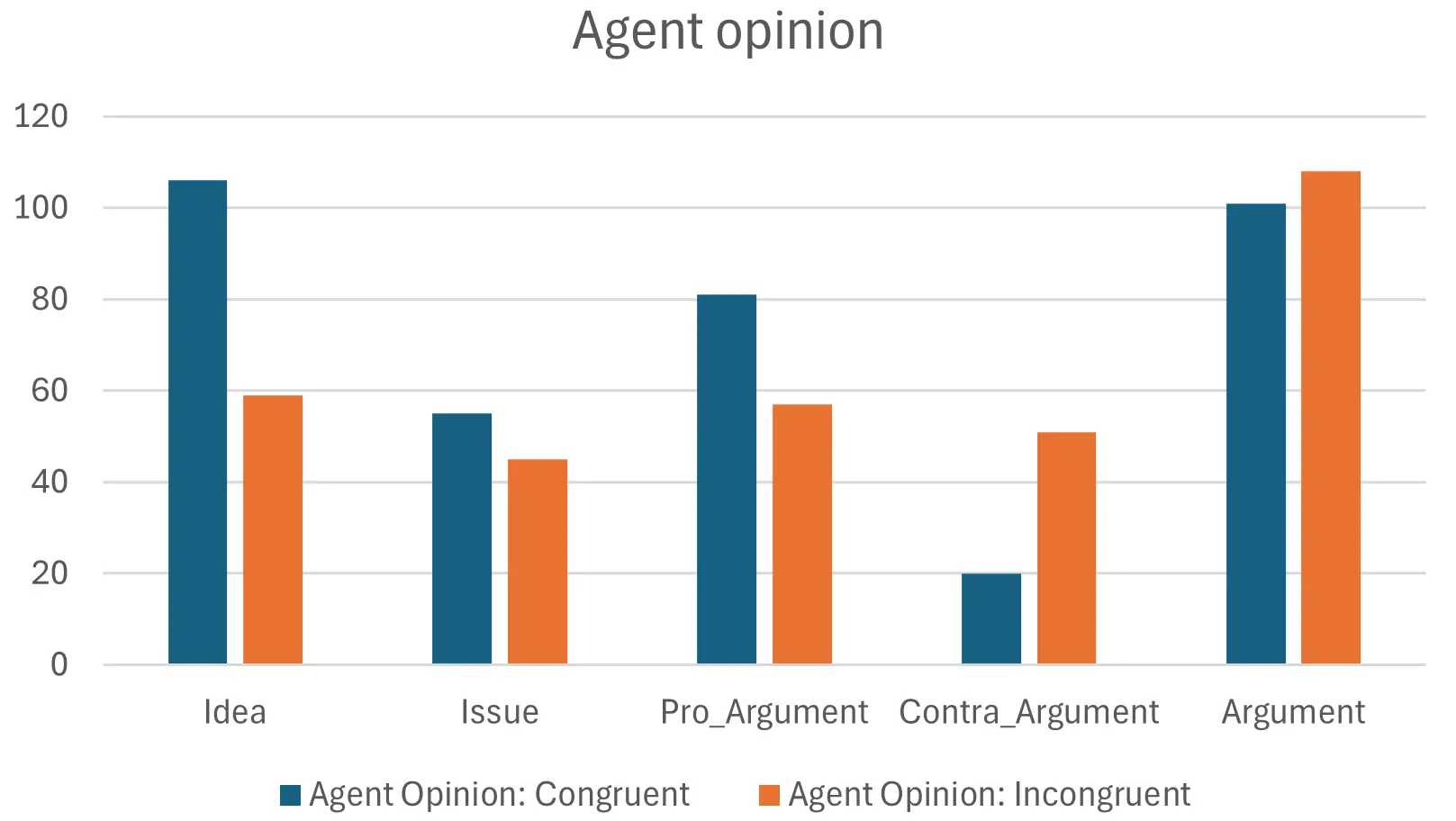

Effect of Agent Opinion: As shown in Figure 2, conversations with a congruent AI agent produced significantly more Ideas (106 vs. 59) and slightly more Pro Arguments. In contrast, agents with incongruent opinions generated more Contra Arguments (51 vs. 20). This likely reflects the distribution in participant views: most participants supported stricter gun laws, so contra arguments were primarily provided by the incongruent AI. These patterns suggest that the AI may have shaped the argumentative direction of the conversation based on its assigned stance.

Figure 2. Distribution of IBIS elements separated by agent opinion. IBIS: Issue-based Information Systems.

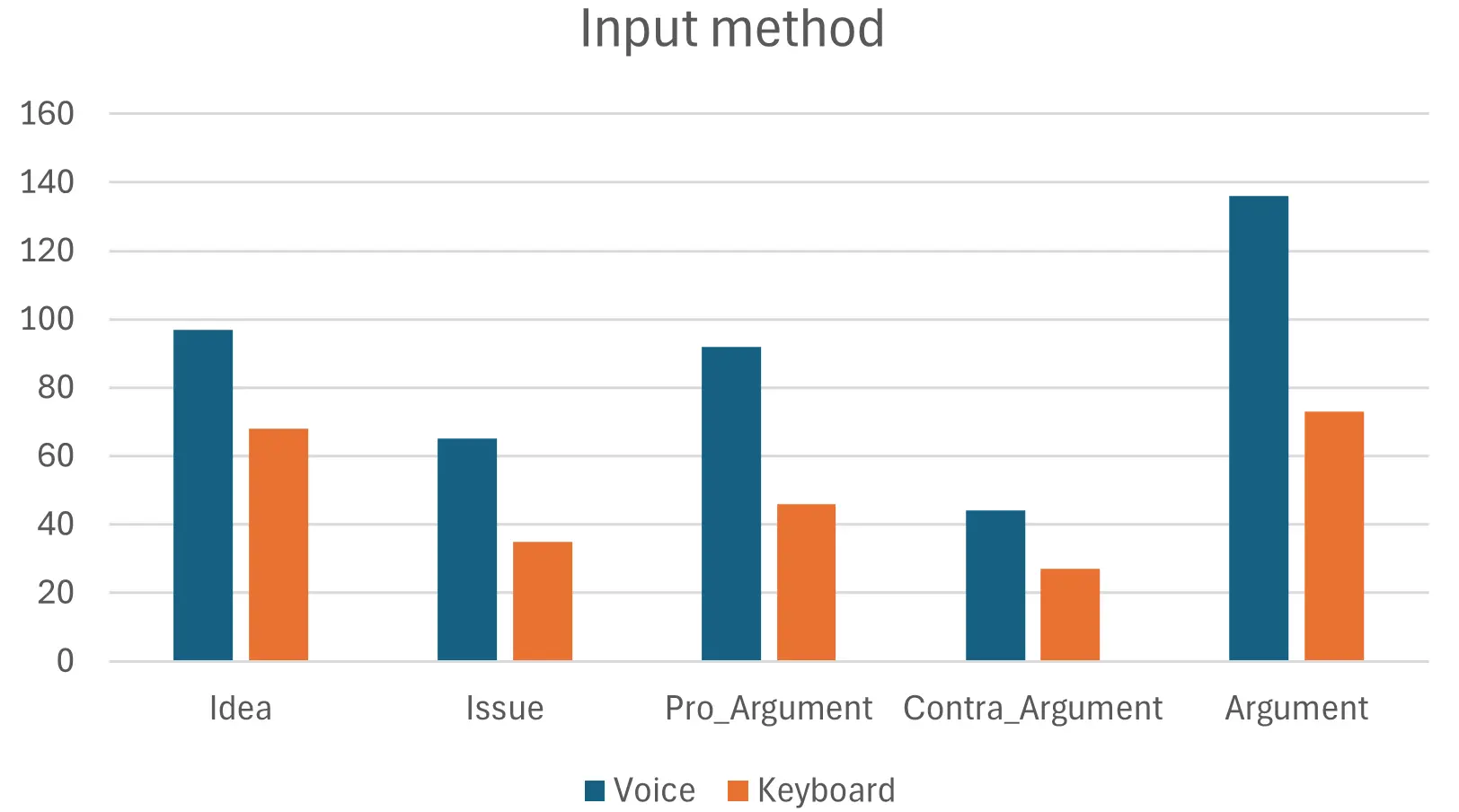

Effect of Input Method: Figure 3 indicates that participants using voice input generated more IBIS elements overall compared to those using keyboard input. Voice-based conversations were richer in Ideas, Issues, and both types of Arguments, suggesting that input modality may influence conversational fluency or expressiveness. This pattern is consistent with prior findings on modality effects in dialogue systems and open-ended tasks[69].

Figure 3. Distribution of IBIS’s elements separated by input method. IBIS: Issue-based Information Systems.

Additional quantitative analysis revealed a strong effect of input modality. Participants using voice input produced significantly more words (M = 234.1, SD = 115.1) than those using keyboard input (M = 65.7, SD = 34.2), t(34) = 5.95, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 1.98 providing decisive evidence in favor of the alternative hypothesis. The AI agent mirrored this pattern, producing more words in the voice condition, t(34) = 3.74, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 1.25. By contrast, agent opinion did not markedly affect participant word counts, t(34) = -0.77, p = .45, Cohen’s d = -0.26, indicating substantial evidence for the null. These results confirm that input modality strongly shapes conversational vocabulary, whereas opinion congruence does not. Independent-samples -tests were conducted across all IBIS coding categories to compare the effects of both agent opinion (congruent vs.incongruent) and input method (voice vs.keyboard). For agent opinion, descriptive statistics showed similar means for Issues, Pro-Arguments, Contra-Arguments and Ideas. The inferential tests showed pronounced differences for contra-arguments and ideas, but not for issue counts and pro-arguments: Issue counts, t(34) ≈ -0.30, p = .76, Cohen’s d = -0.10; Pro-Arguments, t(34) ≈ -1.30, p = .31, d = -0.34; Contra-Arguments, t(34) ≈ 2.37, p = .02, d = 0.17; and Ideas, t(34) ≈ -220, p = .04, d = -0.73. Thus, only two comparisons between the congruent and incongruent reached significance. For input method, descriptive statistics again indicated broadly similar levels of Issues, Pro-Arguments, Contra-Arguments and Ideas between voice and keyboard conditions. The -tests likewise showed notable differences for pro-arguments and ideas: Issues, t(34) ≈ -2.47, p = .02, d = -0.82; Pro-Arguments, t(34) ≈ -3.35, p = .002, d = -1.12; Contra-Arguments, t(34) ≈ -1.42, p = .16, d = -0.47; and Ideas, t(34) ≈ -1.79, p = .08, d = -0.60.

Participant vs. Agent Contribution: The final comparison of IBIS elements focused on the number generated by participants versus the AI agent. The AI agent contributed more Ideas (111) than participants (54). While both parties produced a similar number of Pro Arguments, the agent’s Pro arguments primarily occurred in the congruent condition. This reflects participant distribution: 30 favored stricter gun laws, while only 6 supported looser regulations. This asymmetry also shaped the distribution of Contra Arguments, where the AI agent produced 63 compared to only 8 from participants. In total, the AI agent generated nearly twice as many argumentative elements (136) as the participants (73). This likely reflects a combination of the agent’s elaborative tendencies and the disproportionate argumentative burden it carried in incongruent conditions.

5.4 Qualitative patterns in agent strategy

Beyond IBIS coding, recurring conversational strategies were identified across transcripts. The agent adopted a “Yes, and” approach, analogous to the improvisational comedy technique[70]. It frequently agreed with participant arguments, elaborated on them, and added clarifications, to create a sense of validation and acknowledge user contributions. When the agent’s opinion was incongruent, its strategy shifted to a “Yes, but” style, allowing it to maintain its assigned stance while still engaging with the participants’ points. Notably, the AI agent never directly rejected any participant argument, instead, it opted for soft disagreement or redirection. The AI consistently steered conversations toward solution-focused dialogue, often proposing compromises or policy reforms. It also frequently concluded responses with follow-up questions, sustaining interaction and subtly guiding topic progression. Overall, the agent’s strategy prioritized engagement and tone management, often at the expense of dialectical challenge or ideological depth. Although this approach may have enhanced participant comfort, it appears to have limited the depth and critical rigor of the discussions.

6. Discussion

This study examined how people interact with AI agents embodied in VR while discussing a controversial topic, with a focus on ideological alignment (congruent vs. incongruent), input modality (voice vs. text), and user perceptions. Although no quantitative effects reached statistical significance, the combined quantitative and qualitative evidence revealed several consistent patterns. For example, participants engaged respectfully regardless of alignment, tended to perceive congruent agents as fairer and less biased, and found voice input richer yet more sensitive to bias. Emotional responses remained stable throughout the interactions, suggesting that structured, non-persuasive dialogue can support safe engagement even on divisive issues. We discuss these preliminary patterns and their possible implications for the design of future AI-mediated dialogue systems below.

6.1 Alignment shapes evaluation

Participants rated the AI agent’s arguments as more biased and less strategically reasoned when its opinion diverged from their own. Notably, this perceptual asymmetry emerged despite the agent’s consistent tone and structure across conditions, and even in the absence of any designed persuasive behavior. Qualitative reflections support this pattern, as participants reported feeling less engaged or validated when the AI echoed opposing views. This suggests a key challenge for AI-mediated dialogue: even when content is respectful and well-structured, perceived intent and bias are shaped by ideological alignment. Systems aiming to foster open-minded reflection must account for this asymmetry, as users may interpret disagreement notmerely as content-level opposition, but as social or strategic misalignment. Such perceptions can, in turn, affect trust, perceived fairness, and willingness to engage. This directional pattern aligns with prior work on the similarity-attraction effect, which shows that alignment of beliefs enhances perceived trust and fairness[66]. It also aligns with recent researches on GPT-enabled conversational agents, where users evaluated agents more favorably when responses matched their own views[20,21]. These parallels suggest that ideological congruence influences not only perceived fairness but also the interpretive frame through which users evaluate agent neutrality. Overall, these results indicate that AI agents need to be carefully designed based on whether a single agent will present both congruent and incongruent views or focus on a single stance. Additional design factors also require considering the perspective of the human conversation partner, the goals for the conversation, and whether the setup is one-one vs. multiple humans to one agent (e.g., mediator setting).

6.2 Emotional safety without persuasion

Participant emotional states and gun law opinions remained stable throughout the interactions. This outcome reflects the non-persuasive design of the AI agent, which was intended to express a perspective rather than persuade or change minds. Both the quantitative stability of attitudes and the qualitative data support this interpretation. Interestingly, while opinion remained unchanged, there was a slight, non-significant trend toward increased emotional arousal. This suggest that users found the conversation cognitively or emotionally engaging without pressure. Qualitative data reinforce this: several participants noted that the agent’s calm tone and structured delivery allowed for safe ideological engagement. From a design perspective, these early observations indicate that embodied AI agents in VR may have the potential to support ideologically sensitive dialogue without triggering reactance or defensiveness. Future systems could leverage this emotionally buffered format to scaffold reflection and mutual understanding, prioritizing exploration over persuasion or conversion.

6.3 Limitations in user modeling

Although the AI agent was prompted to form impressions of the participant, its estimates of user stance diverged significantly from participants’ self-reports. This suggests that even in immersive, multi-turn conversations, current AI systems struggle to accurately model user beliefs. This result has several design implications. First, for AI agents deployed in roles requiring perspective-taking or personalization such as coaching, facilitation, or moderation, designers must be cautious about how belief inference is implemented and surfaced. Incorrec estimation of user stance could result in misaligned responses, inappropriate interventions, or diminished trust. Second, our qualitative data suggests that incorrect estimation may not stem solely from AI limitations. Users may modulate their expressions dynamically, avoid direct statements, or shift their tones based on the agent’s stance, highlighting the mutual uncertainty in AI-human communication. These findings indicate the importance of transparent user modeling and alignment with broader literature on communicative adaptation[71], which implies that interlocutors (users and agents) continually adjust expression to perceived social distance or alignment. Applying this lens, future conversational agents may benefit from explicitly conveying uncertainty in their user models.

6.4 Modality and perceived bias

The AI agent’s core traits, including competence, trustworthiness, and humanness, were rated similarly across conditions. However, participants using voice input perceived greater media bias in the agent’s arguments. This may be attributed to the higher social immediacy and affective bandwidth of voice, which can amplify subtle cues in tone, pacing, or emphasis. Because the synthesized voice and text interfaces differed not only in modality, but also in timing and expressivity, modality-related trends should be interpreted cautiously. This result indicates that modality is not a neutral delivery channel. Voice-based interaction may increase scrutiny or sensitivity, especially in ideologically charged contexts. Designers should consider how verbal and paraveral cues contribute to perceptions of neutrality or bias, particularly in spoken interfaces. Systems may need to incorporate explicit tone calibration or meta-communication in voice settings. This pattern is consistent with classical theories of media richness[10] and social presence[11], which proposes that richer modalities heighten interpersonal salience and social evaluation. It also parallels findings from CMC research on online disinhibition[14], where reduced nonverbal cues in text lower perceived interpersonal risks. Together, these frameworks help explain why voice input can magnify bias perception and how its immediacy enhances presence while reducing interpretive distance.

6.5 Human preference and the cost of disagreement

Participants in the incongruent condition were more likely to prefer a human over the AI agent as a conversation partner. This was echoed in qualitative feedback, where users cited the AI’s lack of empathy, depth, or understanding in context of disagreement. While plenty of participants appreciated the agent’s calm demeanor, disagreement appeared to highlight its artificiality and social limitations. This finding has pivotal implications for social acceptance of AI agents in controversial domains. Even when agents perform competently, ideological misalignment can reduce their perceived value as interlocutors. Designers may need to incorporate strategies that acknowledge the emotional stakes of disagreement through empathic statements, reflective prompts, or disclaimers clarifying the agent’s role. This result also connects back to communication accommodation theory[71], which predicts that insufficient adaptive empathy or tone matching can accentuate social distance. Integrating adaptive or self-aware responses may therefore help mitigate the perceived cost of disagreement. Collectively, these findings suggest that ideological alignment, input modality, and agent framing shape how users interpret and engage with AI agents in sensitive conversations. Design strategies that explicitly address asymmetries in perception and trust will be critical for scaling AI-mediated dialogue in emotionally and ethically complex domains.

6.6 Design implications

Although our findings are preliminary, some recurring patterns across alignment, modality, and engagement suggest directions for designing AI-mediated dialogue systems that support sensitive or controversial discussions. Larger studies will be necessary to confirm these trends and extend our analysis, but the following early design implications may help guide researchers and developers working on conversational and embodied AI systems. Transparency of purpose. Participant perceptions of bias and fairness indicate that users interpret disagreement as intentional rather than structural. Future systems should therefore make the agent’s communicative role explicit by signaling whether it is representing a perspective, probing reasoning, or mediating between views. Clear role framing may mitigate perceived bias and help users interpret disagreement as constructive rather than oppositional. Adaptive alignment. Even minimal ideological incongruence altered perceptions of neutrality, suggesting that controlled adaptation may be essential. Agents could modulate empathy, tone, or phrasing to maintain rapport without implying false agreement. Approaches from Communication Accommodation Theory[71], such as strategic convergence and divergence, could inform how systems could be designed to dynamically calibrate alignment in politically or emotionally charged contexts. Modality-sensitive feedback. Voice interactions appeared to intensify sensitivity to bias, consistent with social presence and media richness theories[10,11]. This suggests that voice-based agents require additional bias-mitigation strategies, including tone equalization, expressive disclaimers, or user-controlled playback. Conversely, text-based systems could leverage their lower immediacy to foster reflection, for instance, through delayed prompts or summarization cues. Emotional scaffolds. The relative emotional stability observed across conditions highlights the value of non-persuasive, reflective dialogue for controversial topics. These results suggest that future systems might adopt “expressive” non-persuasive dialogue modes that enable users to articulate their reasoning safely. Interface feedback (e.g., calm vocal tone, neutral gesture) could act as affective scaffolds. Designers should prioritize reflection prompts over counter-arguments, particularly in emotionally charged topics. In immersive settings, embodied cues such as calm gestures, facial expressions or steady gaze could reinforce psychological safety. Human oversight. Participant preferences for human interlocutors during disagreement indicate the potential benefits for hybrid human-AI dialogue models, where human moderators or facilitators can intervene when discussions become contentious. Designing interfaces that make such transitions seamless could enhance trust and ethical accountability.

7. Limitations

Our study has several limitations that inform directions for future work. First, the AI agent, powered by a large language model, drew upon a comprehensive database of arguments and rhetorical strategies, conferring it a structural advantage over participants in terms of content depth and fluency. This knowledge asymmetry may have influenced participants’ perceptions of the agent’s competence or contribution, particularly regarding argumentative quality and conversational flow. While such asymmetries are inherent in AI-assisted designs, they are not necessarily undesirable. In certain contexts, the AI’s superior knowledge can be leveraged to enrich dialogue, introduce novel perspectives, or scaffold participant reasoning, provided the design ensures that this advantage supports rather than overshadows human agency.

Second, participants in the voice input condition experienced technical latency due to real-time transcription and processing. This introduced occasional delays in turn-taking, probably disrupting the perceived naturalness of the conversation or amplified impressions of bias and control. While these bottlenecks reflect current technological constraints, they may not generalize to future systems with faster and more seamless voice interaction.

Third, the visual design of the AI avatars, although deliberately moderate in realism to avoid Uncanny Valley effects, may have affected perceptions of humanness or emotional capacity. Subtle visual cues, such as facial expressiveness or gaze behavior, were not systematically manipulated but could have shaped participant impressions. Given our study incorporated both direct and indirect measures of humanness to mitigate this confusion, future work should explore how embodiment design choices modulate trust, empathy, and perceived agency.

Fourth, the study examined a five-minute conversation about a politically charged topic (gun laws) with a relatively small and demographically homogeneous sample (N = 36, divided across four conditions). These constraints limit the generalizability of our findings to longer or more naturalistic interactions, other controversial issues, and more diverse populations. Because the agent was designed to be congruent or incongruent with each participant’s own stated opinion, cultural background was not part of the manipulation. However, future work should assess how cultural backgrounds shape conversational styles and engagement with an agent. The short duration may have restricted the emergence of complex conversational dynamics, attitude shifts, or subtle constructs such as comfort or bias, which may require extended exchanges to detect. As an initial study, our design prioritized breadth of factors over depth within each condition. Combined with the modest sample size, this approach reduced statistical power and might explain the absence of significant effects in some quantitative measures. Post-hoc sensitivity analyses indicate that with this sample, the study had 80% power to detect large main effects (Cohen’s d ≈ 0.96), but could be only sensitive to very large interaction effects (d ≈ 1.9). We therefore acknowledge that our sample is underpowered for small or medium effects, aiming to surface early patterns and design-relevant insights to motivate and inform future, larger-scale, adequately powered studies. While a within-subjects design could have offered increased statistical power, it posed methodological challenges for this context. Experiencing both congruent and incongruent agents, as well as both voice and text inputs, would have made the manipulations highly transparent and introduced carryover effects[36]. Even counterbalancing cannot reliably eliminate such biases, as recent work indicates[37]. To preserve internal validity in this sensitive setting, we therefore selected a between-subject design, preventing direct comparison of conditions and reducing participants’ ability to infer the manipulations.

Another limitation worth noting is that the IBIS coding was conducted by a single researcher. Future work should involve multiple researchers in coding the conversation analysis to assess reliability and enhance methodological rigor.

Finally, while our adapted and single-item scales provided broad coverage of relevant perceptions, they may have lacked the sensitivity to detect fine-grained differences. Future work should address this limitation by employing larger or more targeted samples, extending interaction periods, and using validated multi-item instruments to better capture nuanced responses to AI-mediated dialogue.

8. Future Work

Our study offers an initial look at how people engage with AI agents during ideologically sensitive conversations in immersive environments, suggesting several directions for future exploration. First, the role of input modality needs to be further explored since our between-subjects design revealed minimal impact on most agent perceptions, apart from higher perceived bias in the voice condition. Future within-subject or longitudinal designs could examine how voice and text shape engagement, expression, and comfort over time. Hybrid systems that enable modality switching may further enhance user agency and adaptability.

Another direction involves the alignment of user and agent viewpoints. Although ideological congruence influenced perceptions of argument quality and human preference, it did not consistently affect evaluations of competence or humanness. Understanding how trust, responsiveness, and strategic adaptation develop in mixed-alignment conversations, particularly when agents acknowledge disagreement, uncertainty, or shared goals, could yield valuable insights.

Beyond one-on-one interactions, AI’s role in facilitating human-to-human dialogue is a promising area, with agents serving as moderators, reframers, or empathy scaffolds in contentious group discussions across domains such as education, civic deliberation, and therapy.

Our findings indicate the importance of aligning conversational goals with system framing. Not all dialogues aim to persuade; many seek understanding, reflection, or co-expression. Nevertheless, persuasion with LLMs remains an active research area[19]. Future systems could draw on theoretical models of dialogue, such as Walton’s dialogue types[72] or deliberative discourse[73], to adapt agent strategies and transparency mechanisms to user intent and context.

9. Conclusion

This study examined how people engage with AI agents during challenging conversations in immersive virtual reality, manipulating input modality (text and voice) and agent opinion (congruent and incongruent) to examine responses to real-time conversation with a large language model embodied as a human-like virtual character. Although emotional states and opinions remained largely unchanged, participants’ perceptions of the agent’s arguments, bias, and role were influenced by viewpoint alignment and modality. Qualitative insights revealed that participants were consistently aware of the agent’s stance and often appreciated its emotionally neutral demeanor. These findings indicate both the opportunities and challenges of designing AI-mediated dialogue systems. Rather than serving as direct substitutes for humans, AI agents can offer a structured, low-conflict space for engagement, particularly when they are transparent about their role, avoid overt persuasion, and adopt socially responsive framing. As AI becomes increasingly integrated into social and civic life, the focus should extend beyond how human-like these systems appear or sound. Equally important are questions of the roles they should fulfill, the types of disagreements they can effectively mediate, and the kinds of conversations they are designed to enable.

Supplementary materials

The supplementary material for this article is available at: Supplementary materials.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Human-AI Experience (HAX) Lab members for early pilots and feedback on the system and study design.

Authors contribution

Rueb F: Conceptualization, methodology, software, formal analysis, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing, visualization, investigation, project administration.

Sra M: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing, visualization, investigation, supervision, project administration.

Conflict of interest

Misha Sra is an Associate Editor of Empathic Computing. Another author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical approval

The study involving human participants was reviewed and approved by the UCSB Human Subjects Committee (Protocol No. 24-24-0559).

Consent for publication

All study participants provided informed consent before the start of the study.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

The data and materials could be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.

Copyright

©The Author(s) 2025.

References

-

1. Abrami G, Bundan D, Manolis C, Mehler A. VR-ParlExplorer: A hypertext system for the collaborative interaction in parliamentary debate spaces. In: Zheng Y, Boratto L, Hargood C, Lee D, editors. Proceedings of the 36th ACM Conference on Hypertext and Social Media; 2025 Sep 15-18; Chicago, USA. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2025. p. 177-183.[DOI]

-

2. Kamoen N, Liebrecht C. I need a CAVAA: How conversational agent voting advice applications (CAVAA) affect users’ political knowledge and tool experience. Front Artif Intell. 2022;5:835505.[DOI]

-

3. Hankel S, Liebrecht C, Kamoen N. ‘Hi chatbot, let’s talk about politics!' Examining the impact of verbal anthropomorphism in conversational agent voting advice applications (CAVAAs) on higher and lower politically sophisticated users. Interact Comput. 2025;37(4):221-233.[DOI]

-

4. Moore N, Ahmadpour N, Brown M, Poronnik P, Davids J. Designing virtual reality–based conversational agents to train clinicians in verbal de-escalation skills: Exploratory usability study. JMIR Serious Games. 2022;10(3):e38669.[DOI]

-

5. Dai CP, Ke F, Zhang N, Barrett A, West L, Bhowmik S, et al. Designing conversational agents to support student teacher learning in virtual reality simulation: A case study. In: Mueller F,Kyburz P, Williamson JR, Sas C, editors. Extended Abstracts of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; 2024 May 11-16; Honolulu, USA. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2024. p. 1-8.[DOI]

-

6. Yang FC, Acevedo P, Guo S, Choi M, Mousas C. Embodied conversational agents in extended reality: A systematic review. IEEE Access. 2025;13:79805-79824.[DOI]

-

7. Reeves B, Nass C. The media equation: How people treat computers, television, and new media like real people and places. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1996.

-

8. Slater M. Place illusion and plausibility can lead to realistic behaviour in immersive virtual environments. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2009;364(1535):3549-3557[DOI]

-

9. Edmondson A. Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Adm Sci Q. 1999;44(2):350-383.[DOI]

-

10. Daft RL, Lengel RH. Organizational information requirements, media richness and structural design. Manag Sci. 1986;32(5):554-571.[DOI]

-

11. Short J. The social psychology of telecommunications. Contemp Sociol.. 1979;7(1):32-33.[DOI]

-

12. Gunawardena CN. Social presence theory and implications for interaction and collaborative learning in computer conferences. Int J Educ Telecommun. 1995;1(2):147-166. Available from: https://www.learntechlib.org/p/15156/

-

13. Gallois C, Giles H. Communication accommodation theory. In: Tracy K, Ilie C, Sandel T, editors. The International Encyclopedia of Language and Social Interaction Secondary; Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons; 2015. p. 65-108.[DOI]

-

14. Suler J. The online disinhibition effect. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2005;2(2):184-188.[DOI]

-

15. Fang CM, Liu AR, Danry V, Lee E, Chan SW, Pataranutaporn P, et al. How AI and human behaviors shape psychosocial effects of extended chatbot use: A longitudinal randomized controlled study. arXiv:2503.17473 [Preprint]. 2025.[DOI]

-

16. Bigman YE, Gray K. People are averse to machines making moral decisions. Cognition. 2018;181:21-34.[DOI]

-

17. Sun H, Zhang Z, Mi F, Wang Y, Liu W, Cui J, et al. MoralDial: A framework to train and evaluate moral dialogue systems via moral discussions. In: Rogers A, Boyd-Graber J, Okazaki N, editors. Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers) ;2023 Jul; Toronto, Canada. Kerrville: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2023. p 2213-2230.[DOI]

-

18. Schoenegger P, Salvi F, Liu J, Nan X, Debnath R, Fasolo B, et al. Large language models are more persuasive than incentivized human persuaders. arXiv:2505.09662 [Preprint]. 2025.[DOI]

-

19. Rogiers A, Noels S, Buyl M, De Bie T. Persuasion with large language models: A survey. arXiv:2411.06837 [Preprint]. 2024.[DOI]

-

20. Kim A, Dennis A, Smith E. Conversational agents powered by generative artificial intelligence improve understanding for those worried about controversial topics. In: Proceedings of the 58th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences; 2024 Jan 7-10; Hawaii, USA. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press; 2025. p. 2698-2707.[DOI]

-

21. Lu L, Tormala ZL, Duhachek A. How AI sources can increase openness to opposing views. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):17170.[DOI]

-

22. Vanneste BS, Puranam P. Artificial intelligence, trust, and perceptions of agency. Acad Manag Rev. 2025;50(4):726-744.[DOI]

-

23. Lv D, Sun R, Zhu Q, Zuo J, Qin S, Cheng Y. Intentional or designed? The impact of stance attribution on cognitive processing of generative ai service failures. Brain Sci. 2024;14(10):1032.[DOI]

-

24. Parenti L, Marchesi S, Belkaid M, Wykowska A. Exposure to robotic virtual agent affects adoption of intentional stance. In: Ogawa K, Yonezawa T, Lucas GM, Osawa H, Johal W, Shiomi M, editor. Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Human-Agent Interaction; 2021 Nov 9-11; Japan. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2021. p. 348-353[DOI]

-

25. Martingano AJ, Hererra F, Konrath S. Virtual reality improves emotional but not cognitive empathy: A meta-analysis. Technol Mind Behav. 2021.[DOI]

-

26. Hadjipanayi C, Christofi M, Banakou D, Michael-Grigoriou D. Cultivating empathy through narratives in virtual reality: A review. Pers Ubiquit Comput. 2024;28(3):507-519.[DOI]

-

27. Grech A, Wodehouse A, Brisco R. Designer empathy in virtual reality: Transforming the designer experience closer to the user. In: De Sainz Molestina D, Galluzzo L, Rizzo F, Spallazzo D, editors. Proceedings of IASDR 2023: Life-changing Design; 2023 Oct 9-13; Milan, Italy. 2023.[DOI]

-