Yuichiro Fujimoto, Faculty of Advanced Science and Technology, Ryukoku University, Kyoto 612-8577, Japan. E-mail: yfujimoto@rins.ryukoku.ac.jp

Abstract

Aims: This study aims to investigate the relationship between eye movement behaviors and social competence, particularly focusing on listening patterns in multi-person conversations. The goal is to identify objective, quantifiable behavioral indicators of social competence to inform the development of assessment tools and training interventions.

Methods: A three-person setting was designed with two conversational partners and one primary listener, and immersive eye-tracking data were collected using Microsoft HoloLens 2 during conversations on naturalistic topics. Social competence was rated by a clinical psychiatrist using standardized behavioral criteria, while analysis targeted three pre-selected indicators: nodding frequency, selective attention allocation to speaker’s regions of interest (head versus shoulders), and vertical gaze stability during listening.

Results: The results revealed that nodding frequency showed a strong positive correlation with social competence scores, indicating its potential as a robust nonverbal biomarker. Participants with higher social competence demonstrated greater attention to the speaker’s head region while minimizing focus on less informative areas such as the shoulders. Furthermore, individuals with higher scores exhibited significantly lower vertical gaze dispersion, reflecting more focused and stable attentional control during social listening.

Conclusion: This study establishes reliable eye movement-based indicators of social competence, highlighting their potential for assessing and enhancing social skills in real-world interactions. By integrating multimodal behavioral analysis, the findings provide a theoretical and technical foundation for developing personalized, real-time feedback systems for social competence training.

Keywords

1. Introduction

The study of human eye movement behavior is of great significance, especially in understanding its role in social interactions. Eye movement not only indicates the distribution of visual attention but also reveals individuals’ cognitive and emotional states during social interactions[1,2]. Traditional eye movement studies often rely on static and well-controlled experimental setups, where subjects are asked to observe static images or pre-recorded videos. Although these studies[3,4] have provided valuable insights, they have significant limitations in simulating the dynamic nature and multimodal characteristics of real social environments, making it difficult to effectively define or interpret appropriate eye movements. In contrast, realistic social interaction, particularly multi-person conversations, presents cognitive challenges that are fundamentally different from controlled laboratory paradigms. Unlike face-to-face dyadic interactions, in multi-person environments, individuals are expected to allocate attention across multiple information sources, integrate visual and auditory cues, and adjust their attentional focus according to conversational dynamics[5].

Notably, in most social situations, individuals frequently play the role of the listener, which is a ubiquitous yet understudied dimension of social competence[6]. Therefore, the analysis of eye movement behavior during the listening phase holds particular research value[7,8]. First, considering the fundamental characteristics of social interaction, listening is an essential component of daily conversations, as individuals convey and understand attention through gaze patterns[9]. Second, compared to eye movements during speaking, which require simultaneous language production, eye movements during listening can independently reveal social cognitive abilities, mitigating the cognitive load generated by multitasking[10]. Listening scenarios impose unique asymmetries distinct from speaking contexts[11]: while speakers directly express their understanding through verbal output, listeners are constrained primarily to nonverbal channels of expression. In this asymmetric communication structure, the listener’s social competence becomes manifest through specific nonverbal behavioral dimensions. Drawing from social cognition theory, three distinct nonverbal dimensions emerge as particularly critical in listening-dominated contexts:

• Active Feedback: the provision of nonverbal feedback signals (primarily nodding) that indicate comprehension, agreement, and encouragement for continued speaking.

• Attention Allocation: the strategic deployment of limited visual resources to high-information-value regions of the speaker’s face (eyes, mouth, etc.) rather than peripheral, non-informative areas.

• Attention Control: the maintenance of focused, stable visual attention on task-relevant information while suppressing task-irrelevant eye movements and managing distractions in multi-speaker environments.

These three dimensions together constitute a meaningful behavioral profile of social listening competence, particularly relevant in conversational contexts. To examine these dimensions objectively, this study adopted a listening-dominated experimental design (approximately 90% listening, 10% brief responses). This proportion not only reflects engagement patterns in specific real social contexts (e.g., meeting discussions, classroom learning), but more importantly, minimizes the noise interference from verbal feedback on eye movement data.

To obtain data with higher ecological validity while maintaining experimental control, this study used Microsoft HoloLens 2 as an eye movement data collection tool. The HoloLens 2’s inside-out tracking enables naturalistic head movement during multi-person interaction without external markers. Critically, it provides synchronized measurement of both gaze position and head movement, which is essential for objectively measuring the nodding dimension. This synchronized gaze-head capability is unavailable in lightweight mobile eye-tracking systems, which typically track gaze only. While the HoloLens 2 introduces trade-offs (device weight ~645 g, restricted field of view ~52° horizontal), these constraints were applied uniformly across all participants and are addressed in our limitations discussion. The device provides high-precision eye tracking in naturalistic augmented reality environments, capturing multimodal behavioral information (gaze, head movements, spatial position) beyond what traditional 2D laboratory settings permit. Although we did not fully utilize the interactive functions of augmented reality in this study, the device’s capabilities offered a strong technical foundation for our investigation.

Based on the above background, this study is dedicated to answering the following research questions:

1) Primary Research Question:

What specific eye movement patterns distinguish individuals with different levels of social competence during listening-dominated triadic conversation scenarios?

2) Sub-Research Questions:

RQ1: Does nodding frequency, as a critical nonverbal feedback behavior that signals understanding and social reciprocity, correlate with social competence levels?

RQ2: Do gaze-allocation patterns reflecting preferential attention to high-information-value speaker regions (head/face) while minimizing focus on non-informative peripheral areas (shoulders) predict social competence levels?

RQ3: Does gaze stability, reflecting sustained focused attention on facial information despite multi-speaker complexity and distractions, correlate with social competence levels?

To address these questions, we designed a three-person interaction scenario involving two conversation partners and one primary listener. Participants mainly observed and listened to natural conversations on predetermined topics while providing brief responses at appropriate moments. During the experiment, we utilized voice identification technology to distinguish between different speakers, enabling analysis of subjects’ attention allocation patterns toward specific speakers.

This study has two key contributions:

On one hand, we established a more realistic experimental paradigm of a two-person conversation plus a listener. Using a 90% listening and 10% brief response design, we captured listeners’ eye movement behaviors in a natural conversation setting, bridging the gap between traditional static 2D experiments and real-world social situations.

On the other hand, based on a psychiatrist’s social competence ratings, we identified three eye movement behavior indicators which were significantly associated with high social competence, directly corresponding to the three theoretical dimensions outlined above: nodding frequency, attention allocation to speakers’ key regions, and vertical gaze stability. These quantitative indicators provide a behavioral foundation for the objective assessment of social competence. In particular, they provide empirical evidence for developing eye movement-based intelligent social skills training (SST) systems.

We believe that these findings will contribute to the understanding of the role of eye movement behavior in social cognition and help the future construction of personalized, real-time feedback tools for social competence enhancement.

2. Related Work

2.1 Traditional eye-tracking techniques and experimental paradigms

As a core tool for exploring human visual attention and cognitive processes, eye-tracking technology has developed from theory-driven approaches toward application-oriented methods[12,13]. Early eye-tracking research mostly employed static paradigms in which participants observed preselected images[14] or videos[15]. By analyzing basic statistical metrics such as fixation duration, saccade paths, and pupil diameter changes, these studies inferred cognitive load and attentional allocation[16]. Such traditional investigations have accumulated a rich theoretical foundation in reading[17], visual search[15], and scene perception[14,18], establishing a logical chain from eye-movement behavior to cognitive processes.

With the expansion of paradigms from solitary tasks to dyadic interactions[19,20], eye tracking began to reveal the dynamics of visual behavior in social contexts. In face-to-face or video-mediated exchanges, participants’ gaze shifts closely align with topic transitions[21]. However, traditional setups, limited to two-dimensional screens and fixed arrangements, struggle to fully replicate the complexity of natural social environments.

2.2 Social attention in multiparty conversations

In conversations involving three or more participants, individuals face far greater cognitive demands than in dyadic interactions. Participants must rapidly shift visual attention among multiple channels while integrating nonverbal feedback to maintain conversational coherence[2,22]. Changes in fixation rate and duration at turn-transition points reflect the combined effects of social expectations, role switching, and cognitive load[23]. Joint attention[24], has been noted as the foundation for collaboration, encompassing not only simple gaze following but also complex processes of intention understanding and social cognition. Subsequently, a social gaze space framework[25] was proposed. This framework identifies five basic gaze states, whose dynamic combinations yield twenty-five possible dyadic interaction patterns within a two-dimensional social gaze space.

2.3 Data collection in immersive settings

Virtual reality has revolutionized experimental control and 3D spatial data acquisition. Wearable eye trackers have overcome laboratory constraints, allowing participants to move freely during interaction tasks while recording precise head movements and gaze coordinates[26]. The Microsoft HoloLens 2, equipped with advanced tracking technology, achieves high accuracy in static scenarios, while its calibration algorithm significantly reduces setup time. An independent assessment[27] indicates that while HoloLens 2 enables practical eye-tracking in immersive settings, achieving research-grade signal quality depends critically on rigorous recalibration. Calibration algorithms can shorten setup time but may introduce systematic biases due to imaging and estimation methods; such limitations should be transparently reported and controlled in experimental design[28]. Challenges in data collection also include environmental adaptability and noise reduction. Visual convergence conflicts in VR can introduce data anomalies[29], while sensor fusion techniques can mitigate motion artifacts.

2.4 Eye-movement data analysis methods

With the accumulation of large-scale eye-movement datasets, analysis methods have evolved from manual area of interest (AOI) definitions toward automated, intelligent approaches. Emerging techniques include dynamic, adaptive AOI segmentation and scanpath similarity algorithms such as ScanMatch[30]. Deep-learning-based sequence-prediction models, exemplified by DeepGaze III[31] and related frameworks, leverage long short-term memory[32] and Transformer architectures[33] for scanpath modeling. Automated feature extraction and temporal clustering enable detection of microsaccades, fixation shifts, and sustained gaze patterns, providing fine-grained characterization of attention flow in complex social scenarios[34]. Iwauchi et al.[35] developed a novel eye-movement analysis method combining fixation heat maps and convolutional neural networks, significantly enhancing the identification accuracy of children and adults with neurodevelopmental disorders from facial expression eye-tracking data. Overall, proper event-detection algorithms and transparent reporting of classification parameters are essential to ensure the comparability and interpretability of results[36].

3. Methods

3.1 Participants

We obtained eye movement data from normally developed adults on campus. A total of 17 graduate students from the fields of biology, information, and materials sciences were recruited for this study. All participants were native Japanese speakers (14 males and 3 females) aged between 23 and 30 years (mean = 23.47, standard deviation (SD) = 2.54). All participants had no known visual impairment or neuropsychiatric disease. To ensure the scientific and ethical compliance of the experimental data, all participants signed an informed consent form before the experiment began, and the relevant procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Nara Institute of Science and Technology. All collected experimental data were anonymized, personal identifying information was completely desensitized, and participant recordings were only available to authorized experts for scientific research analysis.

3.2 Experimental apparatus and setup

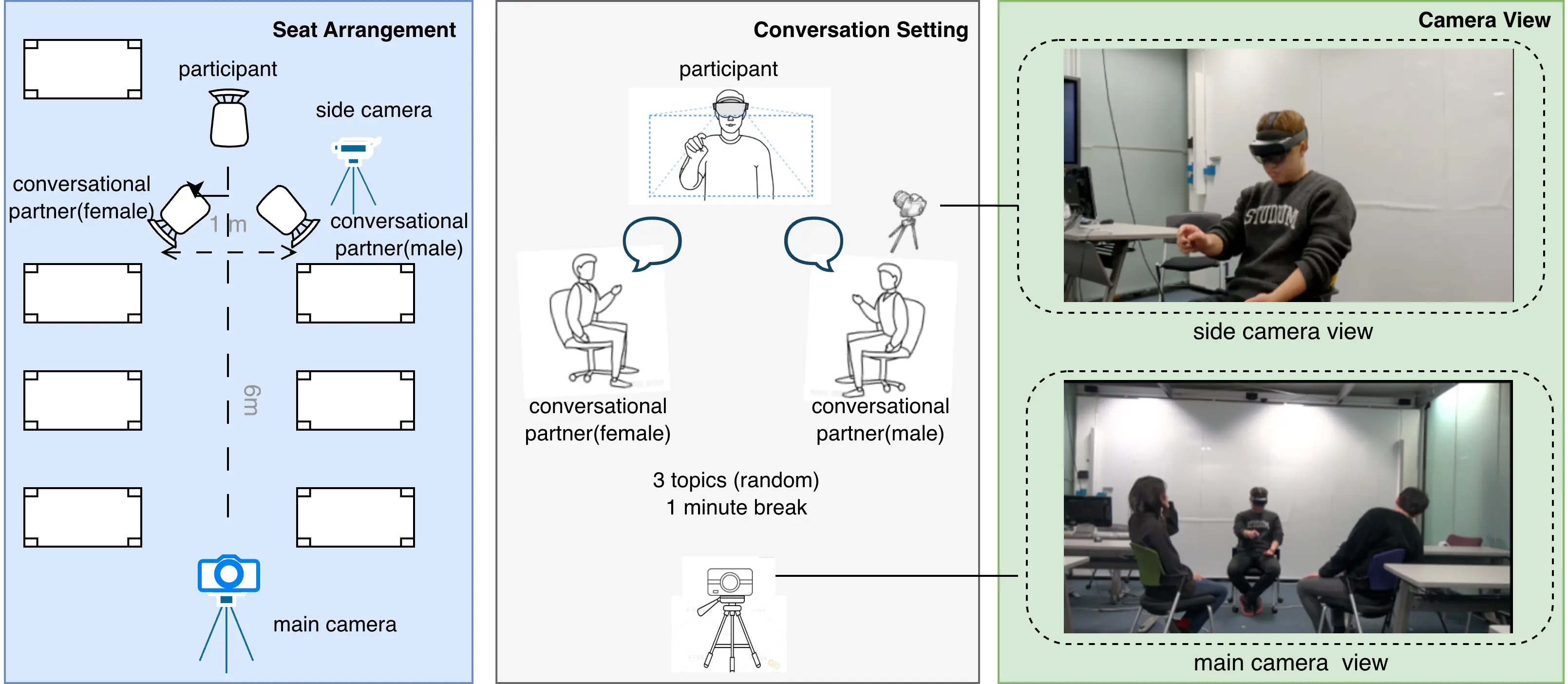

The experimental site was a quiet conference meeting room with consistent lighting and noise conditions. Three people were arranged in each round of the experiment: two conversational partners and one subject as a listener. The three seats were arranged in an equilateral triangle, with the subject facing the camera. See Figure 1 for the specific arrangement. The listener wore a Microsoft HoloLens 2, and the two conversational partners were placed in front of the participant at a distance of about 6 meters. In order to fully record the experimental process, this study set up a Nikon high-definition camera 5 meters in front of the subject for overall image acquisition, and placed a side camera (recorded from a mobile phone, Google Pixel 6a) on the left side of the subject for local close-ups. The side camera was operated by the conversational partner seated on the right.

3.3 Procedure

Participants were required to complete the following experimental process, and all steps were supervised by a dedicated person to ensure standardized operation:

1) Participants first filled in two self-assessment questionnaires (Kikuchi Social Skills Scale-18 (Kiss-18) and Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale-Japanese (LSAS-J)), which measure social skills, interaction fluency, and social anxiety levels, respectively.

2) Participants spent 20-25 minutes learning the gestures and operation interface of HoloLens 2 under the guidance of a researcher and performed at least one sight calibration procedure to ensure the accuracy of the collected data. Given that some participants were not familiar with AR devices, the duration of the learning phase was adjusted based on their familiarity and proficiency with the gestures and interface.

3) Prior to the experimental session, the HoloLens 2 eye tracking system was calibrated for each participant. The device employs a five-point calibration procedure where participants fixate on predefined points in the visual field.

4) Participants were required to listen to three independent conversations between two conversational partners around preset topics. Each conversation was triggered by the participant’s own gesture operation of the “start” and “end” buttons to collect eye movement data. Each conversation lasted between 1.5 and 2.5 minutes. All participants spoke with the same group of conversational partners, and the roles of the conversational partners did not change. A one-minute break was set between each conversation to prevent fatigue. In the meantime, participants removed the HoloLens 2. Before starting the next conversation task, calibration was performed again.

5) After all the conversations were over, participants were asked to complete a questionnaire to provide feedback on their subjective experience and suggestions.

3.3.1 Initial questionnaires

Before the experiment began, participants were administered two questionnaires: the Kiss-18 and LSAS-J. The Kiss-18 questionnaire covers 18 items and uses a 5-point scale to evaluate the participants’ interpersonal communication skills and interaction smoothness. The LSAS-J, a Japanese version of the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale developed by Michael R. Liebowitz, evaluates social anxiety by measuring discomfort when being watched and tendencies to avoid anxiety and fear. It is considered one of the effective tests for detecting social anxiety disorders. Scores on the LSAS-J range from 0 (no anxiety) to 3 (severe anxiety), with avoidance probabilities from 0 (no avoidance) to 3 (high likelihood of avoidance).

3.3.2 Gaze data collection interface

We developed a software application for the HoloLens 2 to collect eye movement data from participants, designed with a minimalist interface featuring only ‘Start’ and ‘Stop’ buttons for ease of use. Participants were required to calibrate the device once before starting the actual data collection. The interface cleared all buttons from the field of view when the ‘Start’ button was pressed, beginning the recording of eye movement data. Upon conversation completion, the participant summoned the ‘Stop’ button via voice control and pressed it to conclude the session. Simultaneously, a first-person perspective video was recorded to aid in subsequent data analysis.

3.3.3 Dialogue and interaction protocol

The experimental dialogue was conducted by a male and a female student, both of whom were graduate students from the same institution and had received topic training to ensure that the rhythm of each dialogue was natural and smooth. The content of the dialogue was based on three pre-set daily topics. Some sessions were designed with scenarios requiring the subjects to make short answers or confirmations to enhance the naturalness and sense of participation in the dialogue. The listening-dominated protocol was employed because listeners are primarily constrained to nonverbal channels, making their social competence manifest through specific indicators like nodding and gaze control. Participants were free to make natural body movements during the experiment to avoid deliberate restraints that would affect their natural interactive behavior.

3.3.4 Expert evaluations

Two experimental recordings (overall and local videos) were evaluated by a psychiatrist from Nara Medical University using a comprehensive social competence assessment protocol. The rater was a mid-career clinician with over 20 years of clinical experience. He has conducted SST and has performed the social competence assessments used in this study for over a decade. Social competence level was quantified solely by the social competence score, the last and most comprehensive dimension of the clinician’s multicomponent evaluation manual. The social competence score was based on a strictly standardized clinical protocol with explicit behavioral anchors for each scale point to ensure consistency. This choice reflects that overall social competence integrates listening, speaking, requesting, and declining behaviors into a single, clinically validated index.

The Social Competence Score was rated on a 5-point scale (1 = inadequate, 2 = below average, 3 = average, 4 = above average, 5 = excellent), according to the following behavioral criteria:

• Listening: attention and genuine engagement with the speaker, including affirmatory feedback such as appropriate nodding, back-channeling, and expressions of empathy.

• Speaking: appropriateness of verbal content, sensitivity to the listener’s responses, and real-time adjustment of speech based on the conversational partner’s cues.

• Requesting: clarity in expressing assistance needs, receptivity to the other’s suggestions, and maintenance of a positive interpersonal tone—even when negotiating or dealing with refusal.

• Declining: delivery of refusals with valid reasoning, expression of regret or politeness, and proposal of acceptable alternatives to maintain rapport.

Each domain is defined by explicit behavioral anchors for every scale point. For example, a 5 on listening indicates natural, context-sensitive nodding and verbal empathy that clearly convey understanding, whereas a 1 reflects behaviors that fail to signal attention or may even convey disinterest. While this comprehensive SST manual includes multiple domains for various social scenarios, the psychiatrist specifically applied the listening domain for this study. This domain was selected to ensure the assessment was strictly aligned with the experimental task’s listening-dominated context.

3.4 Statistical analysis

All analytical procedures were performed following data processing and feature extraction, ensuring that the results were both robust and reproducible. The analysis workflow comprised several steps: data cleaning, event detection, AOI assignment, feature calculation, and statistical evaluation.

3.4.1 Data cleaning and preprocessing

Raw gaze and head movement data were collected from the participants using the HoloLens 2 headset. All analyses were implemented in Python, leveraging pandas for structured data processing, numpy for numerical operations, scipy for statistical testing, and matplotlib and seaborn for figure generation. After evaluating raw data quality, 6 outlier samples (e.g., due to tracking loss or instability) were excluded, leaving 45 final valid samples across 17 participants (each with 3 videos recorded).

3.4.2 Event detection

For gaze sampling, we used the native-frequency eye-tracking data (50-55 Hz) collected from the HoloLens 2 eye tracker. Additionally, concurrent video recording was captured at approximately 26-28 Hz for facial landmark detection. The two data streams were synchronized using their timestamps for subsequent post-processing and analysis. We employed a velocity-based classification algorithm to distinguish between fixations and saccades, following established protocols in eye-tracking research. For behavioral feature extraction, we implemented different detection criteria optimized for different analysis requirements: for head movement analysis, nodding behavior was manually annotated from ground truth data to ensure accuracy, as automated detection of subtle head gestures proved challenging in our mixed-reality environment. For AOI-based attention analysis, we used a refined fixation detection approach with angular velocity criterion (30°/sec threshold) and minimum temporal duration constraints for fixations (≥ 100 ms) and saccades (≥ 20 ms), which provided robust identification of intentional gaze patterns toward speaker regions. For spatial attention distribution analysis, fixation centers were extracted using an optimized velocity threshold approach, enabling precise calculation of gaze dispersion patterns across the visual field.

3.4.3 AOI definition and detection

Speaker AOIs were robustly defined via post-hoc facial landmark detection. Using OpenCV and custom Python scripts, five facial landmark keypoints (left/right eye, nose tip, mouth left/right corners) were extracted to outline anatomical AOIs: (1) Head AOI (the bounding box covered a square from the top of the head to the chin); (2) Shoulder AOI (the rectangular area below the head AOI, the width of which was estimated based on the dataset). Each AOI tracked the apparent movement of the speaker’s head.

3.4.4 Speaker identification

To temporally match AOIs with the current speaker, a lightweight voice activity classifier was pre-trained on the raw dataset. Audio streams were processed with librosa and speaker segments were assigned by SVMs based classifier. Finally, gaze point, AOI, and speaker information were thus mapped to the first-person perspective video captured by HoloLens 2.

3.4.5 Feature calculation and selection

Based on established social cognition theory and eye-tracking literature, we focused on three key behavioral dimensions that reflect social competence: nonverbal feedback behavior, selective attention allocation, and attentional control stability.

Nodding Frequency: Head nodding, as a critical nonverbal feedback signal, was quantified through manual annotation of ground truth data. The frequency was calculated as nods per minute during active conversation periods.

Speaker Attention Allocation: To capture selective attention patterns, we computed the proportion of gaze directed toward different speaker AOIs. Specifically, head region attention, denoted as Rhead, was defined as the ratio of gaze samples where participants were fixating within the current speaker’s head AOI to the total number of valid gaze samples (N):

where N is the total number of valid gaze samples, and i indexes each sample. Here, Ifixation(i) is an indicator function equal to 1 if the i-th sample was a fixation, and 0 otherwise; Ihead(gi, AOIspeaker,i) equals 1 if the gaze point gi falls within the speaker’s head AOI in sample i, and 0 otherwise.

Similarly, Shoulder region attention (Rshoulder) was computed as the ratio of gaze samples falling within the speaker’s shoulder AOI:

where Ishoulder(gi, AOIi) indicates whether the i-th gaze point falls within the shoulder AOI, representing less informative peripheral areas.

Vertical Attention Stability: To assess attentional control, we calculated the SD of fixation centers in the vertical y axis, defined as:

where N represents the total number of valid fixation samples, yi is the vertical coordinate of the i-th fixation center, and

3.4.6 Correlation analysis

Correlation between all candidate features and the social competence score (range from 1-5, rated by an expert psychiatrist from Nara Medical University) was evaluated using Spearman’s rank correlation as appropriate (significance threshold α = 0.05). For each participant, eye-movement metrics were aggregated across their three sessions by computing mean values. This resulted in N = 17 independent observations. The analysis focused on the three pre-selected features based on social cognition theory: nonverbal feedback (nodding), selective attention allocation (head/shoulder AOI ratios), and attentional control (vertical gaze stability). To further validate the robustness of the relationship between nodding frequency and social competence scores, and to account for potential confounding factors, such as individual variability in adapting to the headset’s weight, a linear mixed model (LMM) was conducted. In this model, nodding frequency was treated as a fixed effect, while participant ID was included as a random effect to control for the non-independence of observations and for inherent individual differences.

4. Results

4.1 Dataset description

The final dataset comprised 45 high-quality valid samples, derived from 17 participants who each completed three distinct conversation observation tasks (after the removal of 6 abnormal samples due to eye-tracking signal loss, excessive head movement, or audio synchronization issues). The social competence scores, assessed by an experienced clinical psychiatrist using a five-point Likert scale and a comprehensive role-play evaluation (covering eye contact, posture, facial expressiveness, vocal modulation, conversational fluency, and social adequacy), were distributed as follows: 2 (n = 6, 13.3%), 3 (n = 7, 15.6%), 4 (n = 16, 35.6%), and 5 (n = 16, 35.6%).

For between-group comparisons, based on balanced sample size considerations and clinical psychiatrist evaluation practices, the dataset was divided into three groups: the low social competence group (scores 2 and 3, n = 13), the medium social competence group (score 4, n = 16), and the high social competence group (score 5, n = 16). This grouping approach ensures comparable sample sizes across groups, meets the requirements for statistical analysis, and reflects the common stratification approach for social competence levels in clinical assessments. The scale was slightly biased toward higher scores, with the social adequacy dimension as the study’s core outcome variable.

Prior to the conversation observation tasks, all participants completed standardized psychological assessments, including LSAS-J and Kiss-18, which provided complementary measures of social anxiety levels and social competence skills, respectively. The demographic characteristics and psychological assessment results are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2. The psychological profiling revealed a heterogeneous sample with varying degrees of social anxiety and social skills competency, providing an appropriate range for investigating the relationship between individual differences in social functioning and oculomotor behaviors during social interactions.

| Variable | Value |

| Demographics | |

| Total participants, n | 17 |

| Male, n (%) | 14 (82.4) |

| Female, n (%) | 3 (17.6) |

| Age (years), Mean ± SD | 24.7 ± 2.3 |

| Age range (years) | 23-30 |

| LSAS-J | |

| Total score, Mean ± SD | 56.4 ± 20.3 |

| Total score range | 17-105 |

| Fear/Anxiety subscale, Mean ± SD | 32.2 ± 12.5 |

| Avoidance subscale, Mean ± SD | 24.2 ± 8.9 |

| Kiss-18 | |

| Total score, Mean ± SD | 62.1 ± 9.9 |

| Total score range | 47-80 |

| Gender-based Analysis | |

| Male participants | |

| LSAS-J total, Mean ± SD | 58.0 ± 22.1 |

| Kiss-18 total, Mean ± SD | 61.9 ± 9.3 |

| Female participants | |

| LSAS-J total, Mean ± SD | 49.0 ± 6.6 |

| Kiss-18 total, Mean ± SD | 63.3 ± 15.2 |

LSAS-J: Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale-Japanese; Kiss-18: Kikuchi Social Skills Scale-18; SD: standard deviation.

| Classification | n | Percentage (%) |

| LSAS-J Social Anxiety Severity | ||

| Normal (0-29) | 1 | 5.9 |

| Borderline (30-49) | 5 | 29.4 |

| Moderate (50-69) | 8 | 47.1 |

| Severe (70-89) | 2 | 11.8 |

| Very severe (≥ 90) | 1 | 5.9 |

| Kiss-18 Social Skills Level | ||

| Low social skills (< 54) | 4 | 23.5 |

| Moderate social skills (54-62) | 5 | 29.4 |

| High social skills (≥ 63) | 8 | 47.1 |

LSAS-J: Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale-Japanese; Kiss-18: Kikuchi Social Skills Scale-18.

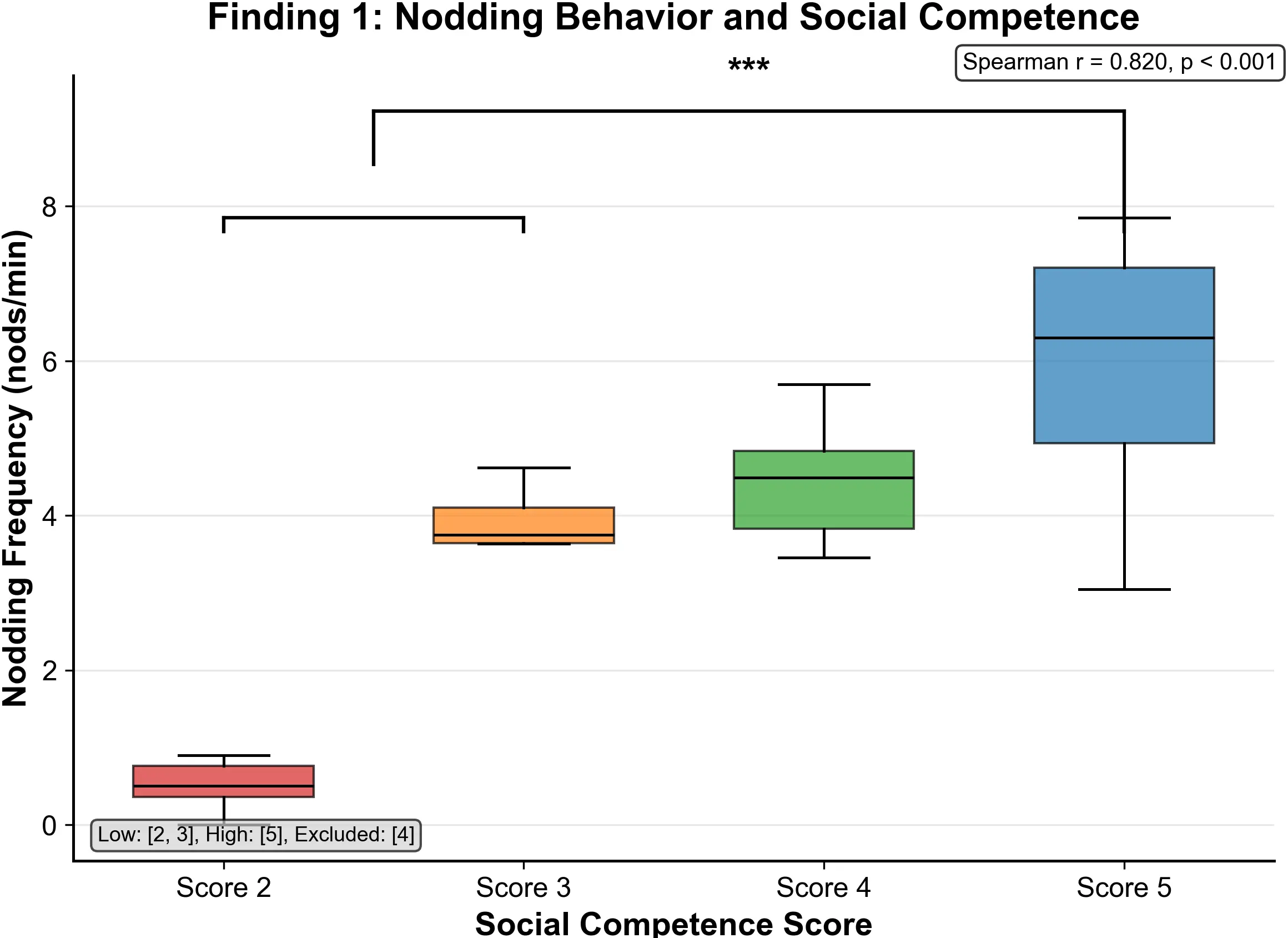

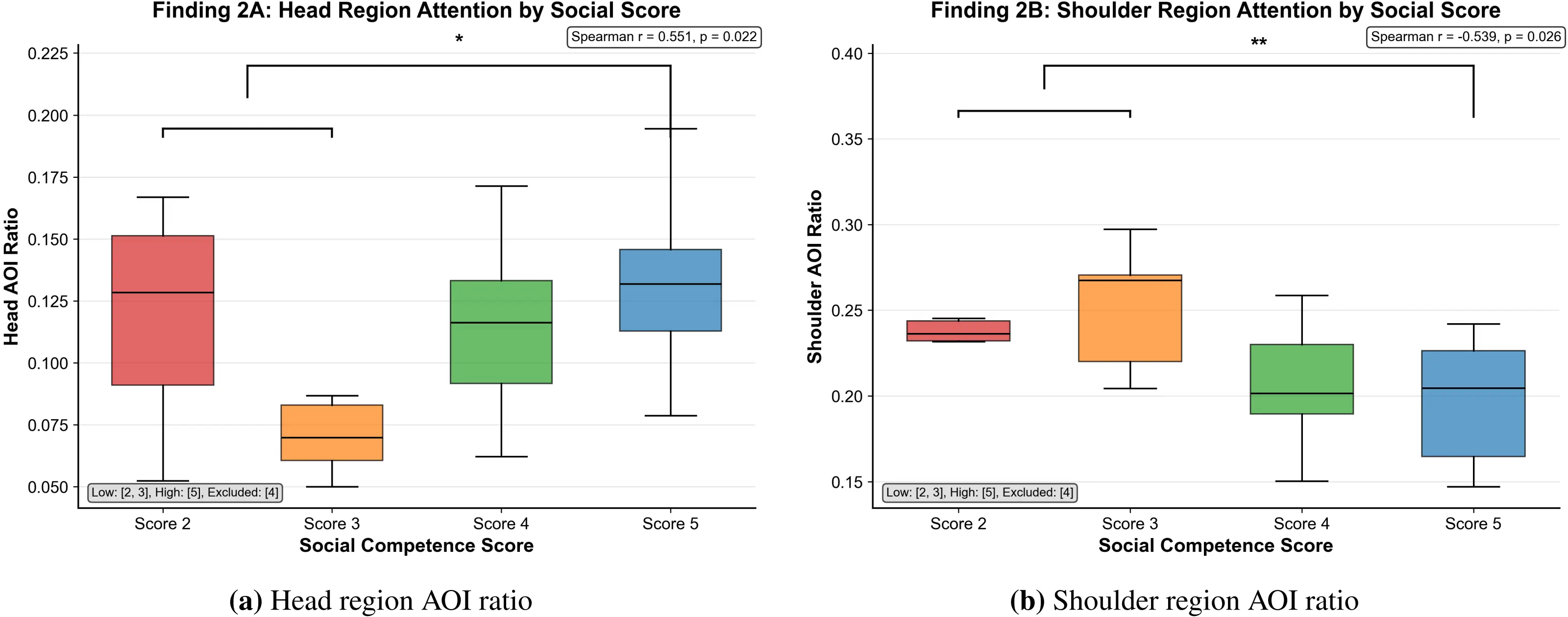

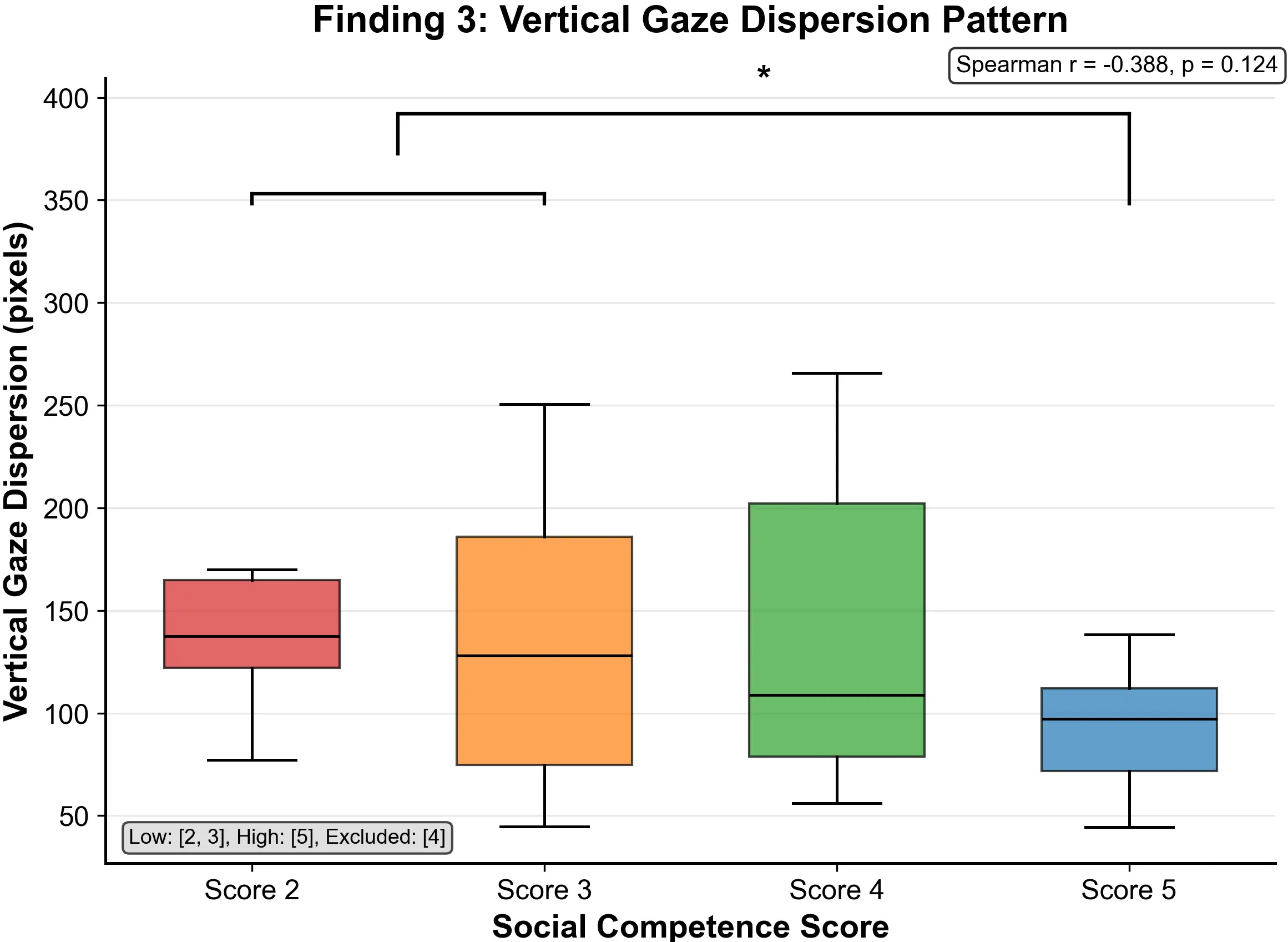

Through a systematic multi-method analytical framework, we identified three key oculomotor behavioral patterns significantly associated with social competence and calculated between-group differences, as detailed below (Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4).

Figure 2. Nodding frequency (nods per minute) by social score. Clear monotonic increase with score, with strong positive correlation r = 0.820, p < 0.001.

Figure 3. AOI ratios (Head and Shoulder) to speaker across social score. Statistically robust findings: Head region attention showed a significant positive trend (r = 0.551, p = 0.0218); Shoulder region attention was significantly negatively correlated (r = -0.539, p = 0.0256), reflecting differential attention allocation strategies. AOI: area of interest.

Figure 4. Vertical gaze dispersion by social score. Narrower vertical dispersion (pixels) in higher competence groups (r = -0.388, p = 0.124) reflects more focused vertical scanning.

4.2 Main findings

4.2.1 Finding 1: Nodding frequency strongly indicates social competence level

Nodding, as a salient nonverbal social signal, exhibited an exceptionally robust positive association with social competence ratings. In our analysis, the position data from HoloLens 2 were initially used to approximate head movements, but manual counting provided more accurate nod frequency results for this study.

As shown in Figure 2, nodding frequency (nods per minute) had a Spearman correlation coefficient of r = 0.820 (p < 0.001) with social scores, marking it as the single strongest behavioral predictor observed.

Between-group comparison analysis showed a clear progressive pattern: the 2-score group demonstrated a mean nodding frequency of 0.52 ± 0.18/min, significantly lower than all other groups; the 3-score group increased to 2.95 ± 0.37/min, indicating emergence of nonverbal feedback; the 4-score group reached 3.47 ± 0.64/min, maintaining a steady interaction rhythm; while the 5-score group peaked at 4.63 ± 0.71/min. Between-group differences were statistically meaningful (p < 0.001), indicating that nodding frequency can effectively distinguish individuals with different social competence levels. The LMM results further bolstered the primary findings. After accounting for individual random effects, nodding frequency remained a highly significant positive predictor of social competence (βstd = 0.684, p < 1e - 8, f2 = 0.880). The marginal R2 (

4.2.2 Finding 2: The high social score group focused more on the speaker’s head area and less on the shoulder area

Visual attention patterns revealed pronounced differences in social-cognitive strategies. Analysis of gaze distribution toward speaker regions showed systematic differences, as depicted in Figure 3.

Visual attention analysis of speakers’ head regions showed a positive trend relationship with social competence. As shown in Figure 3a, head region attention proportion showed a positive correlation trend with social scores (Spearman r = 0.551, p = 0.0218

Between-group comparison showed: the 2-score group participants fixated on the head region for an average of 12.5% of the total time, the 3-score group for 7.0%, the 4-score group increased to 11.8%, and the 5-score group reached 13.8%. There were differences between groups (p < 0.05), indicating that individuals with higher social competence tend to focus attention more on head-face regions that contain rich social information.

Detailed group analysis showed: the 2-score group participants fixated on shoulder regions for 24.1% of total time, higher than other groups; the 3-score group for 24.5%; the 4-score group decreased to 20.5%; the 5-score group lowest at 19.5%. Between-group differences were highly statistically meaningful (p < 0.01), indicating that high social competence individuals can effectively avoid allocating excessive attention to peripheral regions with low information content.

Attention allocation analysis of the shoulder regions revealed a strong negative correlation with social competence. As shown in Figure 3b, shoulder region attention proportion showed a strong negative correlation with social scores (Spearman r = -0.539, p = 0.0256).

Synthesizing these findings, high social competence participants demonstrated precise attentional orientation: they not only recognized which features (facial/head) deserved priority but also effectively minimized focus on non-informative (shoulder, peripheral) cues, reflecting more advanced social-cognitive control and efficient information processing strategies.

4.2.3 Finding 3: High social competence linked to focused vertical gaze patterns

Spatial analysis of gaze distributions (Figure 4) introduced a novel finding: high social competence individuals exhibited markedly lower vertical dispersion of gaze (SD in Y coordinates). As shown in Figure 4, vertical gaze dispersion (pixels) showed a negative correlation trend with social scores (Spearman r = -0.388, p = 0.124).

Specific between-group comparison results showed: the 2-score group’s vertical dispersion averaged 147.5 ± 13.4 pixels, indicating highly scattered vertical scanning patterns; the 3-score group was 130.3 ± 43.8 pixels; the 4-score group decreased to 107.3 ± 47.6 pixels; and the 5-score group lowest at 95.3 ± 17.2 pixels, demonstrating the most concentrated and stable vertical attention pattern. Between-group differences reached statistical significance (p < 0.05), with a medium to large effect size.

In contrast, horizontal gaze dispersion did not differ by social competency (r = -0.006, p = 0.981), with minimal variance across groups. This suggests that all participants engaged in similar horizontal scanning (possibly to track multiple speakers’ locations), but only the higher social competence group achieved a vertically focused gaze, optimizing attentional investment in social communication. This vertical-horizontal attention dissociation may reflect a mature selective-attention mechanism: in multi-person interactions, socially adaptive individuals maintain horizontal flexibility while exerting fine-grained control vertically, focusing on the most socially informative facial areas, usually positioned at a fixed vertical height.

4.3 Post-hoc statistical power analysis

A post-hoc power analysis, conducted with G*Power 3.1[37] (N = 17, α = 0.05, two-tailed), yielded varying levels of statistical power across the four indicators. Specifically, nodding frequency exhibited a high effect size (r = 0.820, p < 0.001) with an achieved power of 0.999. For attention allocation, head AOI attention (r = 0.551, p = 0.0218) and shoulder AOI attention (r = -0.539, p = 0.0256) achieved power values of 0.720 and 0.693, respectively. In contrast, vertical gaze stability showed a smaller effect size (r = -0.388, p = 0.124) with an achieved power of 0.369.

4.4 Self-report questionnaires results

To examine whether participants’ self-perception of social skills and anxiety aligned with objective behavioral indicators, Spearman correlations were computed between Kiss-18 and LSAS-J scores and each of the three primary eye-movement indicators.

Kiss-18 and Eye-Movement Indicators: Kiss-18 total scores showed weak and non-significant correlations with all primary eye-movement indicators: nodding frequency (r = 0.191, p = 0.462), head region attention (r = 0.108, p = 0.680), and shoulder region attention (r = 0.177, p = 0.498).

LSAS-J and Eye-Movement Indicators: LSAS-J total scores demonstrated near-zero correlations with nodding frequency (r = 0.011, p = 0.966) and head region attention (r = 0.237, p = 0.360), but showed a slight positive trend with shoulder region attention (r = 0.254, p = 0.326), approaching marginal significance. Similarly, LSAS-J fear-anxiety subscale scores correlated with shoulder attention (r = 0.257, p = 0.320).

5. Discussion

5.1 Considerations on self-reported measures versus clinician-rated social scores

In the present study, the self-reported questionnaires, including Kiss-18 and LSAS-J, showed no significant correlations with the psychiatrist-rated social competence scores. This discrepancy can primarily be attributed to the inherent subjectivity and variability in self-assessments. Kiss-18 (self-perceived social skills) showed weak correlations with objective indicators: nodding frequency (r = 0.191, p = 0.462), head AOI attention (r = 0.108, p = 0.680), and shoulder AOI attention (r = -0.177, p = 0.498), indicating limited conscious access to one’s own nonverbal behavior. LSAS-J (self-reported social anxiety) showed a near-zero correlation with nodding (r = -0.011, p = 0.966), yet a positive trend with shoulder-region attention (r = 0.254, p = 0.326), suggesting anxiety-related attention biases. In contrast, the psychiatrist-rated evaluations provided multidimensional assessments grounded in professional observation and standardized criteria. Eye-movement indicators showed robust correlations with social competence (r = 0.820, r = 0.551, and r = -0.388) yet minimal correlation with Kiss-18 and weak associations with LSAS-J. This pattern indicates that social competence as manifested in oculomotor behavior represents largely automatic and implicit skill—one that individuals may not consciously monitor or accurately self-assess. The independence of objective eye-movement biomarkers from explicit self-report measures underscores an important distinction: objective behavioral metrics capture implicit, automatic aspects of social competence, orthogonal to conscious anxiety experience or subjective skill perception. This dissociation has important implications for assessment and training: interventions may be more effective if they focus on automatic behavioral modification rather than relying on subjective awareness. Exploratory correlation analyses showed weak correlations between Kiss-18 and expert-rated social competence (r = 0.064, p = 0.806).

Overall, this divergence highlights that social functioning is multi-dimensional: self-reports capture the subjective-affective dimension (internal stress and anxiety), whereas expert ratings focus on the objective-behavioral dimension (perceptible social skills). The results suggest that individuals may perform competently in social interactions despite experiencing significant internal anxiety.

5.2 Interpretation of core findings

5.2.1 Nodding frequency as a robust biomarker for social competence

Our data reveal an exceptionally strong positive correlation (r = 0.820, p < 0.001) between nodding frequency and social competence, confirming that frequent, well-timed nodding is a powerful non-verbal marker of social engagement in group conversations[38]. This pattern is highly consistent across analytic pipelines and remains robust after controlling for other gaze features. This robust finding persists across the full range of competence levels (from 0.52 to 4.63 nods per minute, p < 0.001), demonstrating a consistent individual variation in nodding frequency linked to social competence.

Prior research on nodding has established that head nods serve multiple communicative functions—signaling attention, agreement, understanding, and conversational reciprocity[8]. However, most prior studies have examined dyadic (two-person) interactions in constrained laboratory settings with face-to-face positioning[7]. Our triadic conversation context is cognitively more demanding, requiring participants to process simultaneous input from two speakers while maintaining participatory engagement. The persistence of the exceptionally strong nodding-competence relationship in this more complex context extends prior findings by demonstrating that nodding’s role as a social competence marker generalizes across interactive complexity levels—from dyadic to multi-person scenarios.

Why does social competence manifest as higher nodding frequency? We propose a mechanistic model involving rapid social-cognitive processing: Individuals with higher social competence process conversational content more efficiently. This rapid comprehension translates into appropriately-timed nodding feedback that signals understanding, maintains conversational rhythm, and supports joint attention. In contrast, individuals with lower social competence may struggle with the conversational content processing, resulting in delayed, infrequent, or absent nodding. Supporting evidence for this mechanism comes from the linear, continuous relationship between competence level and nodding frequency (rather than a threshold effect). A threshold would suggest effortful behavioral performance (“if I’m aware I should nod, I’ll do it”), but the gradient suggests automatic, competence-linked variation in nodding—consistent with efficient processing triggering natural nonverbal feedback. Furthermore, nodding showed independence from self-reported social anxiety (LSAS-J: r = -0.011, p = 0.966), indicating that this behavior operates largely outside conscious emotional experience. This automaticity renders nodding resistant to conscious suppression or deliberate control, making it particularly valuable for assessment contexts where behavioral masking may occur.

These findings have implications for assessment, training, and theory. Practically, objective measurement of nodding frequency via eye-tracking provides a quantifiable marker of social engagement that is difficult to fake or deliberately suppress (unlike consciously controlled eye contact or verbal responses). This resistance to conscious control makes nodding-based assessment potentially valuable in clinical settings where detection of behavioral masking is important. For instance, in assessing individuals with social anxiety who might consciously suppress anxiety-driven avoidance behavior while their genuine engagement levels remain suboptimal.

5.2.2 Precise visual attention allocation reflects social information maximization

Socially competent individuals focused their visual attention strategically on the speaker’s face and head while actively avoiding peripheral cues (e.g., shoulders), demonstrating a “head-focused, shoulder-avoidant” attention allocation pattern. This precise attentional strategy matches theories of top-down attention and information value maximization: high social competence is marked by the efficient, strategic deployment of limited visual resources toward the most information-rich regions[39]. The present study identified robust head region attention (r = 0.551, p = 0.0218) and strong negative shoulder region attention (r = -0.539, p = 0.0256) correlating with social competence ratings. These findings demonstrate not merely a trend but systematic, statistically significant attentional strategies reflecting differential social-cognitive control. Recent neuroscientific findings demonstrate that eye movements directly track attended auditory features during selective listening, a phenomenon termed Ocular Speech Tracking[11]. This evidence validates that gaze allocation patterns reflect underlying attentional mechanisms engaged in processing speech. In multi-modal listening scenarios, listeners face strategic challenges in allocating limited visual attention among multiple competing information sources: verbal articulation, facial expressions, hand gestures, and body language. Prior research in social attention[40] has demonstrated that individuals with autism spectrum conditions or social anxiety exhibit systematic gaze avoidance of the face, particularly the eye region, a pattern theoretically linked to threat-salience or reduced social motivation. Our findings present an interesting contrast: rather than face-avoidance, our high-competence group demonstrated face-prioritization coupled with shoulder-avoidance. This pattern reflects a mature, adaptive attentional strategy in which listeners maximize the extraction of emotionally and communicatively salient information (conveyed through facial cues) while minimizing resources devoted to non-informative peripheral regions. The shoulder-region attention bias observed in some lower-competence participants may reflect anxiety-driven attentional patterns, as evidenced by our exploratory finding that LSAS-J showed a positive association with shoulder-region attention (r = 0.254), suggesting an anxiety-related avoidance of facially-concentrated social cues.

The efficiency of this mechanism is evident in the fact that high-competence listeners achieve superior social information processing not through increased overall visual exploration (saccade frequency showed no correlation with competence), but through the strategic allocation of resources—spending less time in non-informative regions and more efficiently extracting information from high-value regions.

5.2.3 Vertical gaze concentration reflects attention control mechanisms

A novel and robust finding is that socially competent individuals exhibited markedly lower vertical dispersion of gaze (SD in Y coordinates: r = -0.388, p = 0.1243), characterized by minimized excess scanning along the vertical axis. Between-group analysis revealed: the low-competence group vertical dispersion averaged 147.5 ± 13.4 pixels (highly scattered vertical scanning); the medium-competence group 107.3 ± 47.6 pixels; and the high-competence group 95.3 ± 17.2 pixels (most concentrated and stable vertical attention pattern). Between-group differences reached statistical significance (p < 0.05), with medium to large effect size. Notably, horizontal gaze dispersion showed no correlation with social competence (r = 0.035, p = 0.818), indicating that the effect is specifically vertical in nature: a spatial dissociation that has theoretical significance.

This vertical-horizontal dissociation reveals a sophisticated attentional mechanism underlying social competence. All participants maintained similar horizontal scanning (possibly enabling tracking of multiple speakers at different horizontal positions), but only higher-competence groups achieved vertically focused gaze, concentrating visual attention within a narrow vertical band. Since critical facial features conveying emotional and social information (eyes, mouth) are arrayed within a restricted vertical space, this vertical concentration represents an elegant optimization: maintaining flexible horizontal exploration while exerting fine-grained vertical control, thereby maximizing simultaneous speaker-tracking and social-information extraction. Neurocognitively, this pattern corresponds to functional specialization of dorsal and ventral attentional networks. The superior vertical concentration in high-competence individuals likely reflects enhanced ventral network efficiency or superior coordination between dorsal flexibility and ventral salience mechanisms, allowing these individuals to maintain both horizontal adaptability and vertical precision simultaneously[41].

Critically, vertical gaze concentration showed a near-zero or weak correlation with explicit self-awareness measures: ystd demonstrated non-significant association with LSAS-J total (r = -0.281, p = 0.275) and with Kiss-18 total (r = -0.179, p = 0.492). This independence from both explicit anxiety experience and conscious social skill awareness indicates that vertical attention control reflects automatic, implicit processes operating largely outside conscious regulation.

Consider behavioral masking scenarios: an anxious individual might consciously amplify nodding frequency or deliberately maintain eye contact to appear competent despite internal discomfort. However, in individuals with high social anxiety, objective gaze metrics like vertical stability are less susceptible to deliberate compensation compared to verbal or explicit nonverbal cues. Simultaneously maintaining convincingly natural vertical gaze concentration while executing conscious behavioral modifications would be cognitively demanding or impossible. This automaticity and resistance to conscious control aligns with neuroscientific evidence from the study[42] that eye movement patterns during effortful listening operate largely outside voluntary regulation. The authors demonstrated that listeners’ eye movement responses to speech reflect implicit, automatic processes rather than consciously controlled gaze deployment. Thus, vertical gaze concentration emerges as a particularly valuable biomarker precisely because it is difficult to fake or deliberately suppress—making it effective for detecting genuine attentional control capacity versus performed or artificially maintained social behavior.

These findings establish vertical attention control as a distinct dimension of social competence, one that captures executive function and automatic attentional processes. The robustness of this relationship, despite the moderate effect size, derives from the metric’s independence from conscious control and its grounding in fundamental neurocognitive mechanisms.

Future research with larger samples should confirm whether vertical gaze stability can serve as a diagnostic indicator of executive dysfunction or attentional control deficits that might manifest in social contexts.

5.3 Masking and the self-report/behavior dissociation

The absence of correlation between LSAS-J and behavioral competence merits discussion. One explanation is anxiety-driven behavioral compensation or “masking”: high-anxiety individuals may consciously elevate nodding frequency to appear competent despite subjective anxiety. However, our findings provide partial evidence against pure masking as the sole mechanism: (1) The strong nodding-competence correlation extends across all competence levels showing a linear gradient rather than a threshold effect, suggesting genuine engagement processes rather than performed behavior; (2) Vertical gaze concentration is subtle and unlikely under voluntary control—individuals cannot consciously suppress vertical dispersion while simultaneously maintaining convincing nodding; (3) Three independent indicators (nodding, head attention, vertical stability) show convergent validity, suggesting a coherent underlying construct. Nevertheless, distinguishing genuine competence from anxiety-driven masking requires future research employing physiological measurement (skin conductance, heart rate variability), post-interaction interviews assessing subjective experience, and explicit masking propensity assessment.

5.4 Implications for SST systems

The identification of these three robust, gaze-based markers has direct translational potential for the design of next-generation social competence training platforms. With classical training approaches often relying on subjective assessment, our findings provide empirically grounded, objective targets for real-time, adaptive feedback:

Real-Time Nodding Monitoring: Integrating head-pose tracking to monitor nod frequency and temporal alignment, systems can deliver instant feedback when nodding is insufficient or inappropriately timed. Advanced modules could analyze the synchrony between nods and conversational content, guiding users to provide relevant non-verbal feedback.

Visual Attention Training: Utilizing gaze tracking, training modules can prompt users to direct their visual attention to the speaker’s face, providing corrective cues when attention drifts to non-informative regions (e.g., shoulders). Programs can be structured with escalating difficulty, from static image practice to video-based scenarios and live interactive tasks.

Spatial Attention Games: Based on the vertical concentration finding, systems may offer gamified tasks requiring vertical gaze stability alongside flexible horizontal exploration, thereby strengthening fine-grained attentional control in realistic social contexts.

Personalized, Adaptive Curriculum: By continuously monitoring user-specific patterns (e.g., low nodding frequency, wide vertical dispersion, shoulder attention), systems can dynamically adjust training modules, allocating more practice to the user’s greatest needs. This ensures maximal relevance and efficiency.

These innovations enable a shift from generic, didactic social skills instruction toward highly individualized, objective, and evidence-driven intervention.

5.5 Limitations and future research

There are several limitations that deserve further discussion:

Limitations of Sample Size. Although the 45 samples in this study achieved sufficient effect size in statistical tests, the sample size was relatively small, and the participants were mainly college students with relatively homogeneous age and cultural background. Future research needs to expand the sample size to include a wider range of age groups and cultural backgrounds to verify the generalizability of the findings. In particular, there may be significant differences in social behavior patterns among children and the elderly, as well as in different cultural backgrounds.

Technical Constraints of HoloLens 2. (1) Visor Opacity: The HoloLens 2’s visual enclosure (the visor) prevents conversation partners from clearly seeing the participant’s eyes and facial expressions. This may reduce the naturalness of their behavioral responses and alter typical social feedback dynamics; (2) Equipment weight and head movement patterns: The HoloLens 2 weighs approximately 645 grams, substantially heavier than mobile eye-tracking glasses (70-100 g) used in naturalistic studies. Since nodding frequency is one of the primary findings, equipment weight could potentially influence head movement patterns systematically. However, the magnitude of between-group differences in nodding (0.52 ± 0.18 to 4.63 ± 0.71 nods/min, approximately 8.9-fold difference) substantially exceeds what would be expected from uniform equipment effects alone. This suggests that social competence differences are the primary driver of observed nodding variation; (3) Restricted field of view: The HoloLens 2 provides approximately 52 degrees of horizontal field of view, substantially narrower than natural human vision (~200 degrees). This artificial restriction may limit natural gaze distribution patterns, particularly for peripheral attention; (4) Spatial mapping and rendering artifacts: While the mixed-reality environment aimed for ecological validity, potential artifacts include minor spatial mapping inconsistencies and rendering quality variations that could subtly affect the perceptual salience or perceived naturalism of conversation partners; (5) Eye-tracking precision and calibration challenges: While the HoloLens 2’s eye-tracking system is generally reliable, it may encounter challenges in certain conditions, such as extreme lighting, which may reduce tracking robustness. Besides, minor calibration drift over the duration of a dialogue task may introduce noise.

Situational Specificity. The conversation scenes in this study are relatively controlled and standardized, but the complexity and diversity of real social situations far exceed the experimental settings. Different types of social situations (formal vs informal, familiar vs strange, conflict vs harmony, etc.) may trigger different eye movement patterns. Future research needs to verify the robustness of the findings in more diverse situations.

Self-Report and Masking. The independence of objective eye-movement metrics from self-reported constructs (Kiss-18, LSAS-J) is theoretically informative but also introduces interpretive complexity. A fundamental limitation is the difficulty in distinguishing genuine social competence from anxiety-driven behavioral compensation. Individuals with high anxiety but low objective eye-movement performance might represent truly struggling individuals; those with high anxiety yet high objective performance might represent individuals engaging in effortful behavioral masking. Objective behavioral metrics alone cannot disambiguate these scenarios.

Future Directions. With the rapid development of eye tracking technology, we can explore the application of more accurate and portable devices in social research in the future. Future studies will employ lightweight, glass-type eye trackers to validate our findings and minimize the potential influence of headset weight on natural social behavior. At the same time, combining other physiological indicators (such as heart rate variability, skin conductance, etc.) may provide a more comprehensive social cognition assessment. The application of machine learning and artificial intelligence technologies will also provide new possibilities for the recognition and analysis of complex eye movement patterns.

6. Conclusion

This study provides clear and robust evidence for how specific eye movement and head gesture patterns relate to social competence in dynamic, multi-person listening interactions. By having participants both listen to and engage in conversations while wearing the Microsoft HoloLens 2, we collected rigorous eye-tracking and nonverbal behavior data in an ecologically valid setting. Three important indicators of effective eye movement were discovered: nodding frequency, attention on the speaker’s key region, and vertical gaze dispersion. These findings demonstrate that effective social behavior depends on well-defined, measurable patterns of attentional control and nonverbal communication, which can be assessed objectively in realistic conversational contexts. Compared to traditional static paradigms, the integration of auditory and visual information in dynamic dialogue scenarios offers a more comprehensive evaluation framework. The potential of our results is substantial. The defined behavior indicators can serve as objective targets for social-skills training interventions and may inform the development of adaptive, real-time feedback systems for individuals with social communication difficulties.

Acknowledgements

The authors used Gemini and Perplexity for linguistic refinement, style polishing, and enhancing the readability of the entire manuscript, including the introduction and discussion sections. These tools also assisted in summarizing existing literature and translating psychiatric evaluation standards from Japanese to English (Section 3.3.4). The authors have reviewed and verified all content and take full responsibility for the originality, accuracy, and integrity of the entire work.

Authors contribution

Fang Y: Conceptualization, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, writing-original draft.

Fujimoto Y: Conceptualization, methodology, writing review & editing, supervision.

Uratani M: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, writing review & editing.

Butaslac I, Sawabe T, Kanbara M, Kato H: Writing review & editing, supervision.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Nara Institute of Science and Technology (No. 2023-I-39).

Consent to participate

All participants provided freely given, informed consent to participate in the studies.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study contain sensitive personal information, including facial images and voice recordings, which cannot be made publicly available to ensure participant privacy and confidentiality. Access to anonymized or aggregated data may be granted upon reasonable request to the corresponding author, subject to institutional and ethical approvals.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant (No.25K01204) and JST ANR-CREST Grant (No.JPMJCR19A5).

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

References

-

1. Laidlaw KEW, Foulsham T, Kuhn G, Kingstone A. Potential social interactions are important to social attention. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 2011;108(14):5548-5553.[DOI]

-

2. Wohltjen S, Wheatley T. Interpersonal eye-tracking reveals the dynamics of interacting minds. Front Hum Neurosci. 2024;18:1356680.[DOI]

-

3. Holmqvist K, Nyström M, Andersson R, Dewhurst R, Jarodzka H, Van de Weijer J. Eye tracking: A comprehensive guide to methods and measures. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2011. Available from: https://research.ou.nl/en/publications/eye-tracking-a-comprehensive-guide-to-methods-and-measures/

-

4. Buehler R, Ansorge U, Silani G. Social attention in the wild-fixations to the eyes and autistic traits during a naturalistic interaction in a healthy sample. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):30102.[DOI]

-

5. Dawson J, Foulsham T. Your turn to speak? Audiovisual social attention in the lab and in the wild. Vis Cogn. 2022;30(1-2):116-134.[DOI]

-

6. Itzchakov G, Haddock G, Smith S. How do people perceive listeners? R Soc Open Sci. 2025;2(4):241550.[DOI]

-

7. Bodie GD. The understudied nature of listening in interpersonal communication: Introduction to a special issue. Intl J Listen. 2011;25(1-2):1-9.[DOI]

-

8. Wolvin AD, Coakley CG. Listening education in the 21st Century. Intl J Listen. 2000;14(1):143-152.[DOI]

-

9. Wohltjen S, Wheatley T. Eye contact marks the rise and fall of shared attention in conversation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 2021;118(37):e2106645118.[DOI]

-

10. Herrmann B, Ryan JD. Pupil size and eye movements differently index effort in both younger and older adults. J Cogn Neurosci. 2024;36(7):1325-1340.[DOI]

-

11. Gehmacher Q, Schubert J, Schmidt F, Hartmann T, Reisinger P, Rösch S, et al. Eye movements track prioritized auditory features in selective attention to natural speech. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):3692.[DOI]

-

12. Kowler E. Eye movements: The past 25 years. Vision Res. 2011;51(13):1457-1483.[DOI]

-

13. Kümmerer M, Bethge M. Predicting visual fixations. Annu Rev Vis Sci. 2023;9(1):269-291.[DOI]

-

14. Loschky LC, Szaffarczyk S, Beugnet C, Young ME, Boucart M. The contributions of central and peripheral vision to scene-gist recognition with a 180° visual field. J Vis. 2019;19(5):15.[DOI]

-

15. Korner HM, Faul F, Nuthmann A. Is a knife the same as a plunger? Comparing the attentional effects of weapons and non-threatening unusual objects in dynamic scenes. Cogn Res Princ Implic. 2024;9(1):66.[DOI]

-

16. Fink L, Simola J, Tavano A, Lange E, Wallot S, Laeng B. From pre-processing to advanced dynamic modeling of pupil data. Behav Res Methods. 2024;56(3):1376-1412.[DOI]

-

17. Hyöna J, Kaakinen JK. Eye movements during reading. In: Klein C, Ettinger U, editors. Eye movement research: An introduction to its scientific foundations and applications. Cham: Springer; 2019. p. 239-274.[DOI]

-

18. Williams CC, Castelhano MS. The changing landscape: High-level influences on eye movement guidance in scenes. Vision. 2019;3(3):33.[DOI]

-

19. Schilbach L, Timmermans B, Reddy V, Costall A, Bente G, Schlicht T, et al. Toward a second-person neuroscience1. Behav Brain Sci. 2013;36(4):393-414.[DOI]

-

20. Canigueral R, Hamilton AFdC. The role of eye gaze during natural social interactions in typical and autistic people. Front Psychol. 2019;10:560.[DOI]

-

21. Dravida S, Noah JA, Zhang X, Hirsch J. Joint attention during live person-to-person contact activates rTPJ, including a subcomponent associated with spontaneous eye-to-eye contact. Front Hum Neurosci. 2020;14:201.[DOI]

-

22. Capozzi F, Ristic J. Attentional gaze dynamics in group interactions. Vis Cogn. 2022;30(1-2):135-150.[DOI]

-

23. Clayman SE. Turn-constructional units and the transition-relevance place. In: Sidnell J, Stivers T, editors. The handbook of conversation analysis. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2012. p. 151-166.[DOI]

-

24. Mundy P. A review of joint attention and social-cognitive brain systems in typical development and autism spectrum disorder. Eur J Neurosci. 2018;47(6):497-514.[DOI]

-

25. Jording M, Hartz A, Bente G, Schulte-Rüther M, Vogeley K. The “Social Gaze Space”: A taxonomy for gaze-based communication in triadic interactions. Front Psychol. 2018;9:226.[DOI]

-

26. Hooge IT, Niehorster DC, Nyström M, Hessels R. Large eye-head gaze shifts measured with a wearable eye tracker and an industrial camera. Behav Res Methods. 2024;56(6):5820-5833.[DOI]

-

27. Aziz S, Komogortsev O. An assessment of the eye tracking signal quality captured in the Hololens 2. In: 2022 Symposium on Eye Tracking Research and Applications; 2022 Jun 8-11; Denver, USA. New York: ACM; 2022. p. 1-6.[DOI]

-

28. Hooge ITC, Nuthmann A, Nyström M, Niehorster DC, Holleman GA, Andersson R, et al. The fundamentals of eye tracking part 2: From research question to operationalization. Behav Res Methods. 2025;57(2):73.[DOI]

-

29. Dymczyk M, Przekoracka-Krawczyk A, Kapturek Z, Pyżalska P. Effect of a vergence-accommodation conflict induced during a 30-minute Virtual Reality game on vergence-accommodation parameters and related symptoms. J Optom. 2024;17(4):100524.[DOI]

-

30. Cristino F, Mathot S, Theeuwes J, Gilchrist ID. ScanMatch: A novel method for comparing fixation sequences. Behav Res Methods. 2010;42(3):692-700.[DOI]

-

31. Kümmerer M, Bethge M, Wallis TS. DeepGaze III: Modeling free-viewing human scanpaths with deep learning. J Vis. 2022;22(5):7.[DOI]

-

32. Hochreiter S, Schmidhuber J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997;9(8):1735-1780.[DOI]

-

33. Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez AN, et al. Attention is all you need. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2017.[DOI]

-

34. Engbert R. Microsaccades: A microcosm for research on oculomotor control, attention, and visual perception. Prog Brain Res. 2006;154:177-192.[DOI]

-

35. Iwauchi K, Tanaka H, Okazaki K, Matsuda Y, Uratani M, Morimoto T, et al. Eye-movement analysis on facial expression for identifying children and adults with neurodevelopmental disorders. Front Digit Health. 2023;5:952433.[DOI]

-

36. Startsev M, Zemblys R. Evaluating eye movement event detection: A review of the state of the art. Behav Res Methods. 2023;55(4):1653-1714.[DOI]

-

37. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39(2):175-191.[DOI]

-

38. McClave EZ. Linguistic functions of head movements in the context of speech. J Pragmatics. 2000;32(7):855-878.[DOI]

-

39. Pearson D, Chong A, Chow JYL, Garner KG, Theeuwes J, Le Pelley ME. Uncertainty-modulated attentional capture: Outcome variance increases attentional priority. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2024;153(6):1628.[DOI]

-

40. Stuart N, Whitehouse A, Palermo R, Bothe E, Badcock N. Eye gaze in autism spectrum disorder: A review of neural evidence for the eye avoidance hypothesis. J Autism Dev Disord. 2023;53(5):1884-1905.[DOI]

-

41. Meyyappan S, Rajan A, Yang Q, Mangun GRM, Ding M. Decoding visual spatial attention control. eNeuro. 2025;12(3):0512-0524.[DOI]

-

42. Cui ME, Herrmann B. Eye movements decrease during effortful speech listening. J Neurosci. 2023;43(32):5856-5869.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite