Abstract

Aims: Sharing a robot’s intentions is crucial for building human confidence and ensuring safety in robot co-located environments. Communicating planned motion or internal state in a clear and timely manner is challenging, especially when users are occupied with other tasks. Augmented reality (AR) offers an effective medium for delivering visual cues that convey such information. This study evaluates a smartphone-based AR interface designed to communicate a robot’s navigation intentions and enhance users’ situational awareness (SA) in shared human–robot settings.

Methods: We developed a mobile AR application using Unity3D and Google ARCore to display goal locations, planned trajectories, and the real-time motion of a Robot Operating System enabled mobile robot. The system provides three visualization modes:

Results: Participants achieved an average SAGAT score of 86.5%, indicating improved awareness of the robot mission, spatial positioning, and safe zones. AR visualization was particularly effective for identifying obstacles and predicting unobstructed areas. In the

Conclusion: A mobile AR interface can significantly enhance SA in shared human–robot environments by making robot intentions more transparent and comprehensible. Future work will include in-situ evaluations with physical robots, integration of richer robot-state information such as velocity and sensor data, and the exploration of additional visualization strategies that further strengthen safety, predictability, and trust in human–robot collaborative environments.

Keywords

1. Introduction

Robots are increasingly deployed in industrial, domestic, and service environments, resulting in more frequent interactions between humans and autonomous systems. As these systems operate alongside people, it becomes essential for users to understand an autonomous agent’s current behavior, intended motion, and decision-making process. This ability to interpret and anticipate robot behavior is commonly referred to as intention readability, which contributes directly to safety, trust, and coordination in human–robot co-located settings[1-9].

Traditionally, interfaces for human–robot interaction (HRI) have focused on one-way communication, allowing humans to issue commands while robots execute them. Although effective for task assignment, such interfaces provide little insight into the robot’s reasoning or planned motion. Communicating intent in an intuitive manner remains challenging, because many systems lack mechanisms for conveying internal state, decision processes, or motion goals in ways that humans can readily interpret. Interfaces that expose a robot’s internal state help make interaction more transparent and user-centered, enabling operators to better understand its goals, performance, and reasoning processes[1,10]. This transparency supports situational awareness (SA), which enables users to perceive, comprehend, and project relevant information about the system and environment[11,12].

Augmented reality (AR) has become a compelling medium for improving human understanding of robot behavior. By anchoring virtual information within physical space, AR provides spatially grounded visualizations that make a robot’s planned actions and navigation behavior more explicit during interaction[13]. Prior works have shown that AR can effectively visualize robot motion intentions[3,14,15], task progress[4,6], traversed paths[5], and internal or sensory states[16,17]. Presenting these cues directly in the user’s environment has been shown to enhance comprehension, increase interaction fluency, and improve user confidence in shared workspaces[3,4].

Recent studies further support the value of AR for intention communication in deployment contexts. For instance, AR-based overlays have been shown to improve trust calibration and coordination in human-robot teamwork, and AR-enabled path and goal displays can help co-workers better anticipate robot actions in shared spaces[18,19]. Similarly, mixed-reality interfaces for industrial or collaborative tasks have demonstrated that making robot intent visually accessible improves task understanding and reduces ambiguity during interaction[20,21]. Collectively, these recent studies highlight a consistent trend: AR-based visualization improves human awareness of what robots will do, where they will go, and how they will behave, especially in co-located settings.

Despite these promising findings, much of the existing work relies on specialized hardware such as projection systems[14,22] or

Moreover, although previous studies have illustrated perceived benefits of AR-based communication, recent surveys highlight that empirical evaluations of SA remain limited[18]. To address this gap, we assess user awareness using a structured Situational Awareness Global Assessment Technique (SAGAT)-based methodology, offering new evidence on how a lightweight mobile AR solution influences mission awareness and spatial awareness in robot-shared environments. This evaluation extends our earlier demonstrations of mobile AR-based human-robot communications[25,26] and contributes toward a deeper understanding of the role of mobile AR in supporting transparency, predictability, and human–robot coordination.

2. Implementation of AR Visualization Interface

We developed a mobile AR application that can be used by a human operator to serve as a visualization interface on which information regarding a mobile robot navigating in the environment can be displayed. The AR application is developed using

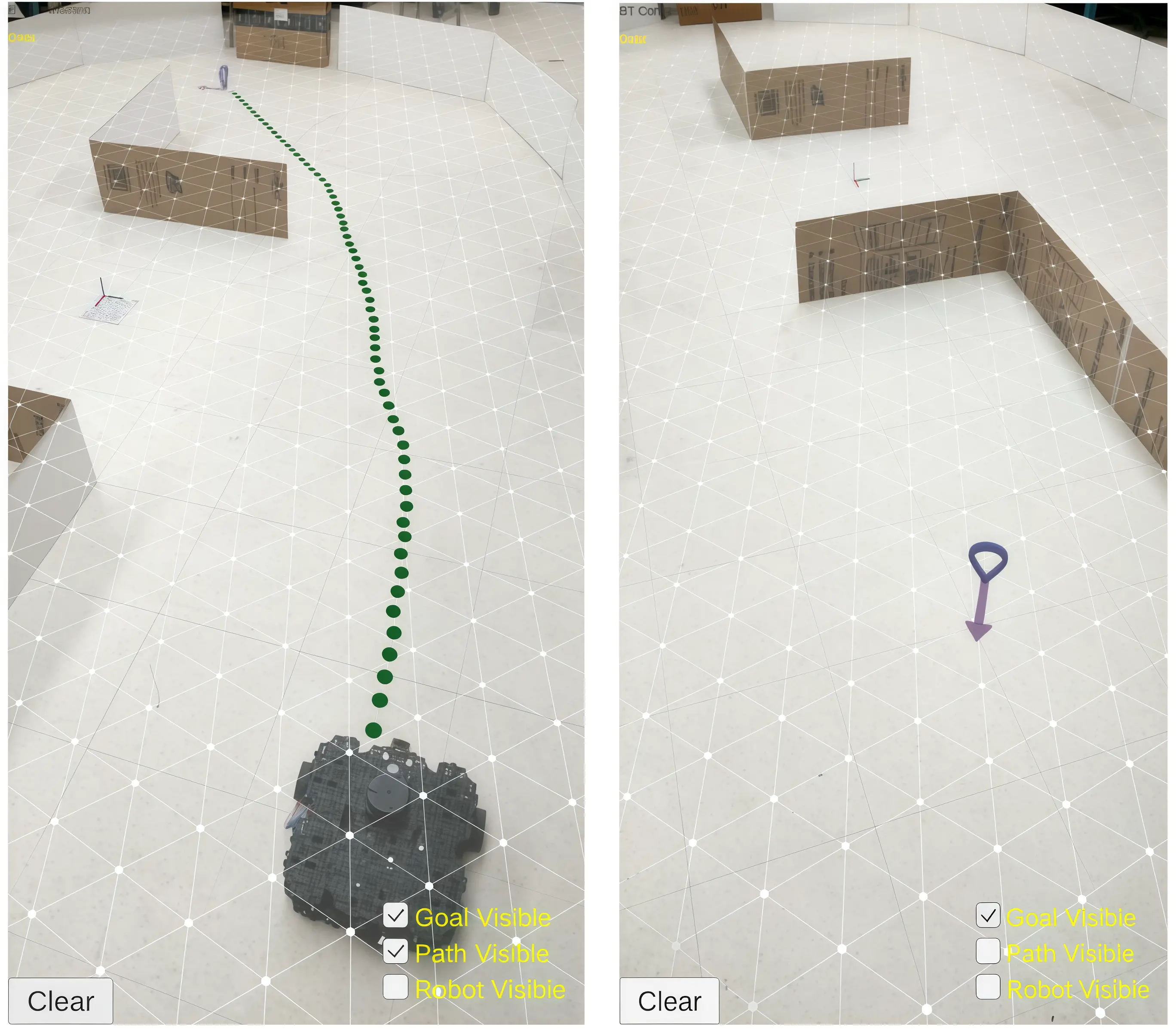

Figure 1. AR interface screenshots. The green dots represent the projected navigation path, and the blue virtual object with purple arrow denotes the target goal pose.

When the AR application launches, it scans the environment and detects feature points, as well as the reference marker, and waits to receive data from the robot system. TurtleBot3, a ROS enabled robot is used as the mobile robot platform for this work, and Bluetooth communication is established between the AR device (smartphone) and the PC running the ROS master. The AR application is provided with three visualization options, namely, Goal Visible, Path Visible, and Robot Visible. On the AR application, when the user selects a specific visualization option, the corresponding ROS topics are subscribed to on the ROS end and seamlessly send data to the smartphone AR device. The navigation coordinate data, which are represented in the right-handed coordinate system in ROS, are converted to the left-handed coordinate system of the AR application before being transmitted to the AR device.

The goal pose of the mobile robot is indicated by a virtual pin-point object with an arrow as shown in Figure 1b. The arrow direction indicates the orientation of the robot at the goal location. When the Goal Visible option is enabled, the AR application sends a goal request to the serial node on the ROS end. The ROS topic/move base/current_goal is subscribed to by the ROS node and the target goal pose is transmitted to the AR application. A new virtual goal object is rendered in the AR scene at the corresponding real-world spatial location.

When a new goal is selected for the robot, a navigation path to the selected target coordinate is computed based on the cost map[28] of the area. If the Path Visible option is enabled in the AR interface, the ROS topic/move base/NavfnROS/plan is subscribed by the ROS node, and waypoint coordinates are sent to the AR application. The waypoints of the planned trajectory are represented by the green virtual sphere objects rendered in the AR scene as shown in Figure 1a.

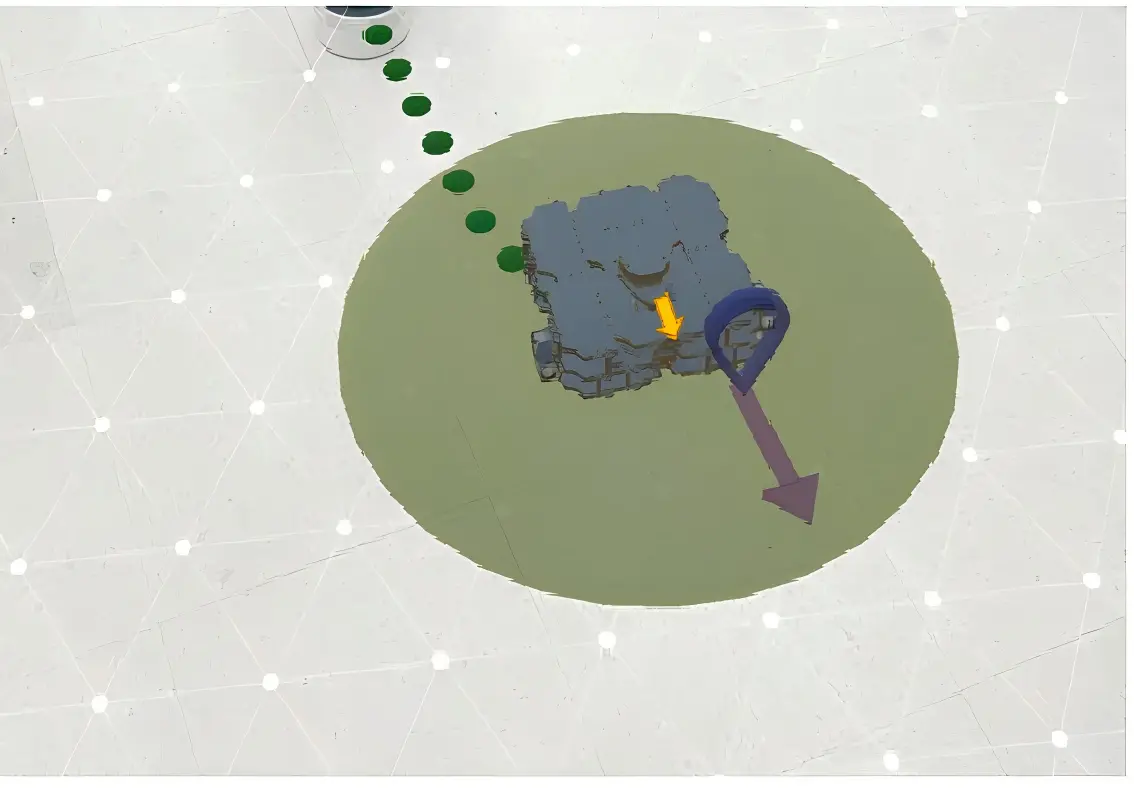

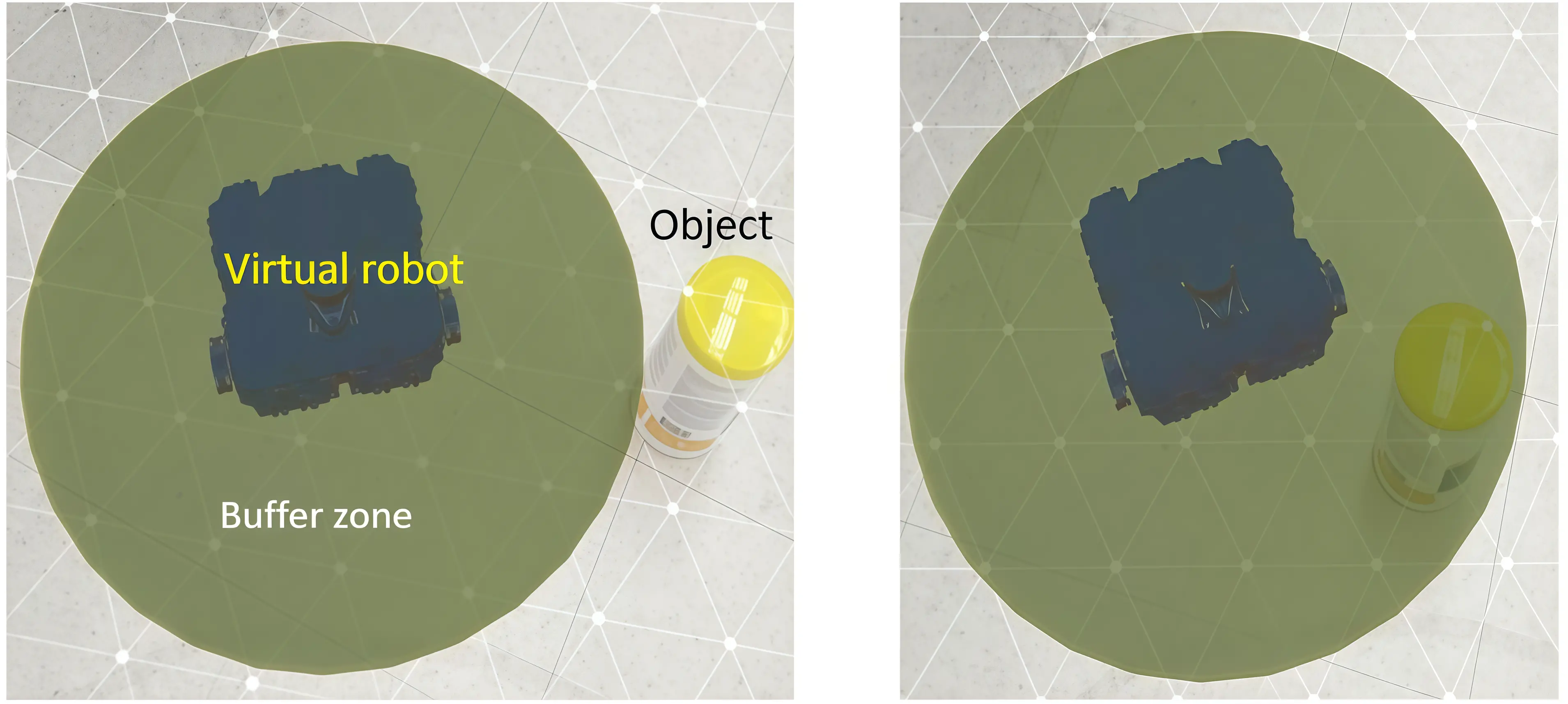

A virtual robot visualization framework helps users to understand the movement of the robot in the absence of a real robot, assuming no dynamic obstacles are present on the path. A CAD model of the robot is exported into the Unity3D environment to get the specific virtual robot model. If the Robot Visible option is enabled, the ROS topic (amcl_pose) is subscribed to by the ROS node, and instantaneous poses of the robot are transmitted to the AR application to visualize the motion of the virtual robot (Figure 2). The virtual robot is also surrounded by a buffer zone visualization (shown as a yellow circular region, see Figure 3) with a radius of 0.5 m (inflation radius is 0.5 m) to indicate a possible obstructed area while navigating through the planned path.

Figure 2. AR visualization of a virtual robot navigation simulation, showing the planned trajectory (green dots), the robot’s final pose with orientation (arrow), and the safety buffer zone (yellow circle) around the virtual robot. An obstacle positioned near the path illustrates how spatial relationships and potential collision regions are conveyed to the user in the augmented scene. AR: augmented reality.

Figure 3. AR visualization of a safety buffer region around the virtual robot. (a) Left: When the object appears outside the buffer region, the robot is considered unobstructed; (b) Right: The object is located inside the buffer zone, representing a potential obstruction. AR: augmented reality.

3. Evaluation of SA

To assess how effectively the mobile AR interface supports users’ understanding of robot navigation intentions, we conducted a structured evaluation based on the SAGAT[11]. SAGAT is a widely used method in human–automation and HRI research for measuring SA by probing a user’s mental model at specific points during a task. It evaluates SA across three levels defined in Endsley’s

In our study, we incorporated a variety of scenarios and questions to evaluate all three levels of SA. Level 1 SA queries assessed users’ ability to directly perceive information shown in the AR scene, such as the robot’s goal location, visible obstacles, or objects positioned along the planned path. These questions measure immediate recognition of elements explicitly presented through the AR visualizations.

Level 2 SA queries examined how well users could comprehend and interpret the information they perceived. For instance, when presented with a planned trajectory, users needed to recognize potential issues or conflicts that might arise along the navigation route. To assess this level, we included scenarios where path–environment interactions introduced possible hazards or constraints, requiring users to move beyond simple perception and form a meaningful understanding of the situation.

Level 3 SA queries evaluated users’ ability to project future states of the environment based on their current understanding. Here, participants were asked to anticipate likely outcomes, such as whether the robot would navigate safely through an area or whether the environment contained unobstructed regions. Visualizations of the robot’s intended motion and path provided cues that enabled users to forecast future events and reason about the robot’s behavior.

Additionally, we considered specific dimensions of SA such as mission awareness and spatial awareness when designing the scenarios and constructing the SAGAT queries[29] to assess how effectively the AR interface supports user understanding. To measure mission awareness, queries asked participants to identify the robot’s navigation goal or infer the intended direction of travel. These questions assess whether the AR cues effectively communicate the robot’s high-level objective. For example, the user should be able to understand how and where the robot is heading and any possible conflicts arising due to the planned trajectory. To measure spatial awareness, queries focused on recognizing obstacles, determining safe versus obstructed regions, and understanding how these elements relate to the robot’s planned path. These queries probe the user’s ability to interpret spatial relationships conveyed through AR overlays such as distances, collisions, and path–object interactions.

Together, the SAGAT queries capture mission and spatial awareness across perception, comprehension, and projection levels. By aligning query design with the visual elements of our AR interface, we establish a direct connection between the interface’s features and users’ cognitive understanding. Table 1 summarizes the full set of questions and associated accuracy rates.

| # | SAGAT Queries | Expected Response | SA Dimensions | Accuracy Rate (%) |

| 1 | Where is the goal location of the robot | At B | L1, Mission, Spatial | 82.76 |

| 2 | What will be the final orientation of the robot? | Toward South-West | L1, Mission, Spatial | 87.93 |

| 3 | Are there any objects along the planned trajectory of the robot that will obstruct its path? | Yes | L1, L2, Mission, Spatial | 98.3 |

| 4 | How many objects encountered along the planned trajectory may obstruct the robot’s path? | Two | L2, Mission, Spatial | 86.2 |

| 5 | How many objects serving as obstacles are present along the planned trajectory of the robot? | One | L2, L3, Mission, Spatial | 81.03 |

| 6 | Which zones may be suitable for users to occupy without worrying about obstructing the robot’s motion in the given environment? | Zone A & C | L2, L3, Spatial | 82.76 |

SA: situational awareness; SAGAT: Situational Awareness Global Assessment Technique.

4. Experiments and Results

4.1 SAGAT assessment

We conducted a user study to evaluate the SA and usability of the AR visualization interface. A total of 58 participants took part in the study, including 14 females and 44 males, with ages ranging from under 20 (n = 2), 21–30 (n = 45), 31–40 (n = 9), and 41–50 (n = 2). Most participants reported prior experience with robotics (86.2%) and augmented reality (79.3%). The study was administered online and followed the SAGAT methodology, in which participants responded to query prompts associated with AR scenarios representing robot goals, planned paths, obstacles, and safe regions in the environment.

To begin, participants were shown two sample AR scenes to familiarize them with the visualization elements. They were then presented with a sequence of screenshots, each illustrating a specific scenario, followed by a SAGAT query. The queries were designed to assess users’ perception, comprehension, and projection of information related to the robot’s mission, planned trajectory, obstacles, and safe zones. Table 1 summarizes the queries and corresponding SA dimensions.

Quantitative SA scores were computed by comparing participant responses with the expected answers. SA performance was determined by how well participants understood the information presented through the various AR visualization features. Queries Q1–Q3 examined Level 1 SA, assessing users’ ability to directly perceive AR information, such as the robot’s mission goal and visually apparent obstacles. These queries primarily targeted the mission awareness dimension, with correct response rates of 81% or higher.

Queries Q4 and Q5 examined users’ awareness of the planned trajectory and the presence of obstacles along or near the robot’s path. Two types of scenarios were presented: one in which obstacles appeared directly on or very close to the path, and another in which an obstacle was positioned near the trajectory but did not obstruct it. A virtual robot with a buffer zone was shown to help users interpret potential collision areas. Participants correctly identified obstacles located on or near the path in 86.2% of cases (Q4). Accuracy decreased to 81% for Q5 when obstacles were positioned just outside the buffer region.

Query Q6 assessed users’ understanding of safe zones, defined as areas in which humans could be present without interfering with the robot’s operation. The combined visualization of the goal, planned trajectory, and buffer zone enabled 82.76% of users to correctly identify unobstructed or safe regions in the environment. Overall, participants achieved an average cumulative SAGAT score of 86.5% across all queries.

4.2 Post-assessment survey

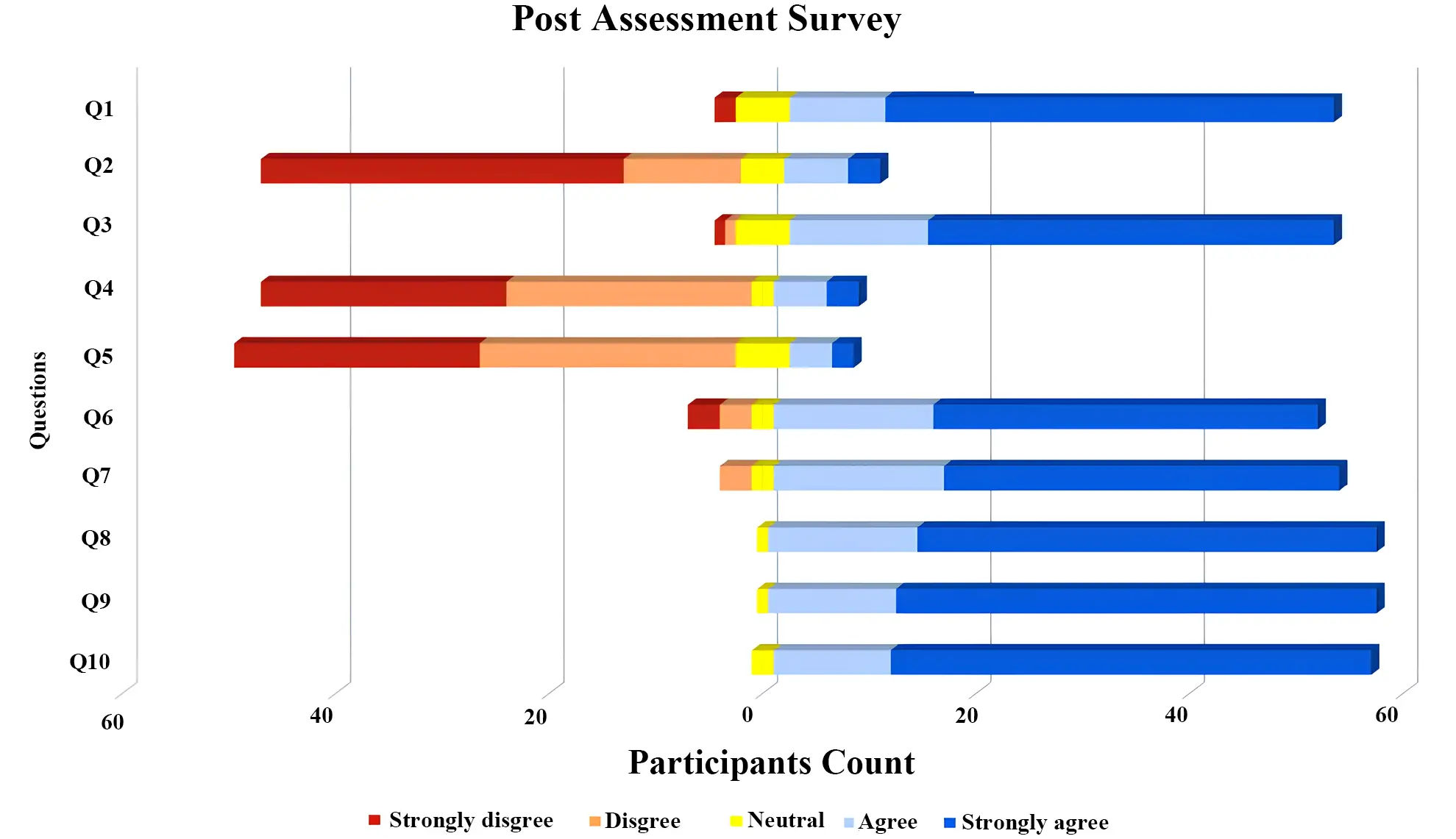

Following the SAGAT assessment, a post-assessment survey was administered to gather participants’ self-ratings of SA and their perceptions of the AR visualization interface. The survey consisted of 10 items on a 5-point Likert scale, including seven positively directed statements and three negatively directed statements. Figure 4 summarizes the distribution of participant responses.

Figure 4. Post assessment survey response. The SAGAT assessment and user survey are available at this link. SAGAT: Situational Awareness Global Assessment Technique.

Across the seven positively directed statements, more than 87.9% of respondents selected agree or strongly agree for each item. Conversely, for each of the three negatively directed statements, over 77.6% of participants selected disagree or strongly disagree. Responses indicated consistent agreement regarding understanding of robot motion, awareness of the environment, and perceived safety when robot intentions were visible in advance.

5. Discussion

The results demonstrate that the proposed mobile AR interface effectively supports users’ SA of a mobile robot’s navigation intentions across perception, comprehension, and projection levels. The average SAGAT accuracy of 86.5% indicates that participants were generally able to interpret the robot’s goal, planned trajectory, and spatial constraints using the AR visualizations. High accuracy on Level 1 queries confirms that goal and obstacle information presented through AR was readily perceivable, while strong performance on Level 2 and Level 3 queries suggests that users could meaningfully interpret and reason about future robot behavior.

The slightly lower accuracy observed when obstacles were positioned near, but not directly within, the robot’s buffer region highlights an important design insight. While the buffer visualization aided users in understanding potential collision zones, interpreting marginal cases requires more nuanced spatial reasoning. This finding aligns with prior work showing that explicit visualization of robot intent improves human comprehension[3,30], however, our results indicate that interpreting intent may become more challenging when environmental constraints are subtle or near boundary conditions. Future designs may benefit from adaptive or graded visual cues that emphasize proximity and risk more clearly.

The post-assessment survey results further reinforce the objective findings. More than 96.6% of participants reported increased confidence and improved understanding of robot motion intentions, indicating that AR visualizations not only enhance measurable SA but also positively influence subjective perceptions of safety and trust. These outcomes are consistent with recent studies demonstrating that AR-based intention communication improves trust calibration and coordination in human-robot

A key contribution of this work lies in demonstrating that these benefits can be achieved using a lightweight, smartphone-based AR interface rather than specialized projection systems or head-mounted displays. Prior studies often rely on such hardware, which can limit scalability and real-world deployment[24,30]. By contrast, the proposed approach lowers the barrier to adoption while still providing meaningful improvements in mission and spatial awareness.

While the results are promising, some limitations of this study should be acknowledged. The evaluation was conducted online using screenshots of the AR setting rather than live interaction with a physical robot, which may affect ecological validity. Additionally, the study focused primarily on navigation-related intent and did not incorporate dynamic obstacles or richer robot-state information such as velocity or uncertainty. Despite these limitations, the consistency between objective SAGAT scores and subjective user feedback suggests that the findings provide a strong foundation for further in-situ evaluation.

6. Conclusion and Future Work

We developed a mobile AR interface designed to enhance users’ SA of a robot’s navigation intentions by making its goals, planned paths, and motion previews more transparent and intuitive to interpret. Evaluation through a SAGAT-based user study demonstrated strong performance across all levels of SA, with participants achieving an average accuracy of 86.5%. Users were particularly successful in distinguishing safe versus obstructed areas, suggesting that the AR visualizations effectively supported interpretation of spatial relationships and potential collision risks. The post-assessment survey further confirmed these results, with 96.6% of participants reporting increased confidence and a clearer understanding of the robot’s intentions after interacting with the interface.

These findings highlight the promise of lightweight, smartphone-based AR systems for improving robot transparency and supporting more intuitive human-robot collaboration, without relying on specialized or costly hardware. Although the study was conducted online and did not include live interaction with a physical robot, the consistently high accuracy rates and positive user feedback provide a strong foundation for transitioning the system to real-world deployment.

Future work will include in-situ evaluations with physical robots, integration of richer robot-state information such as velocity and sensor data, and exploration of additional visualization strategies that further strengthen safety, predictability, and trust in

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the time and effort of the individuals who participated in user studies and their valuable feedback.

Authors contribution

Chacko S: Software, investigation, formal analysis, writing-original draft.

Kapila V: Supervision, writing-review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was determined to be exempt by the NYU IRB, as this research only includes interactions involving survey procedures, interview procedures, or observation of public behavior (including visual or auditory recording).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all participants before participation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Funding

This work is supported in part by the National Science Foundation under DRK-12 Grant DRL-1417769,195 ITEST grant DRL-1614085, and RET Site Grant EEC-1542286.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

References

-

1. Chen JYC, Lakhmani SG, Stowers K, Selkowitz AR, Wright JL, Barnes M. Situation awareness-based agent transparency and human-autonomy teaming effectiveness. Theor Issues Ergon Sci. 2018;19(3):259-282.[DOI]

-

2. Baraka K, Rosenthal S, Veloso M. Enhancing human understanding of a mobile robot’s state and actions using expressive lights. In: 2016 25th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN); 2016 Aug 26-31; New York, USA. Piscataway: IEEE; 2016. p. 652-657.[DOI]

-

3. Walker M, Hedayati H, Lee J, Szafir D. Communicating robot motion intent with augmented reality. In: Proceedings of the 2018 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction; 2018 Mar 05-08; Chicago, USA. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2018. p. 316-324.[DOI]

-

4. Andersen RS, Madsen O, Moeslund TB, Amor HB. Projecting robot intentions into human environments. In: 2016 25th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN); 2016 Aug 26-31; New York, USA. Piscataway: IEEE; 2016. p. 294-301.[DOI]

-

5. Reardon C, Lee K, Fink J. Come see this! Augmented reality to enable human-robot cooperative search. In: 2018 IEEE International Symposium on Safety, Security, and Rescue Robotics (SSRR); 2018 Aug 06-08; Philadelphia, USA. Piscataway: IEEE; 2018. p. 1-7.[DOI]

-

6. Leutert F, Herrmann C, Schilling K. A Spatial Augmented Reality system for intuitive display of robotic data. In: 2013 8th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI); 2013 Mar 03-06; Tokyo, Japan. Piscataway: IEEE; 2013. p. 179-180.[DOI]

-

7. Palmarini R, del Amo IF, Bertolino G, Dini G, Erkoyuncu JA, Roy R, et al. Designing an AR interface to improve trust in Human-Robots collaboration. Procedia CIRP. 2018;70:350-355.[DOI]

-

8. Pascher M, Gruenefeld U, Schneegass S, Gerken J. How to communicate robot motion intent: A scoping review. In: Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; 2023 Apr 23-28; Hamburg, Germany. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2023. p. 1-17.[DOI]

-

9. Tsamis G, Chantziaras G, Giakoumis D, Kostavelis I, Kargakos A, Tsakiris A, et al. Intuitive and safe interaction in multi-user human robot collaboration environments through augmented reality displays. In: 2021 30th IEEE International Conference on Robot & Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN); 2021 Aug 08-12; Vancouver, Canada. Piscataway: IEEE; 2021. p. 520-526.[DOI]

-

10. Alonso V, de la Puente P. System transparency in shared autonomy: A mini review. Front Neurorobot. 2018;12:83.[DOI]

-

11. Endsley MR. Design and evaluation for situation awareness enhancement. In: Proceedings of the Human Factors Society Annual Meeting; 1988 Oct 24-28; Anaheim, USA. Los Angeles: Sage Publications; 1988. p. 97-101.[DOI]

-

12. Endsley MR, Garland DJ. Situation awareness analysis and measurement. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2000.[DOI]

-

13. Walker M, Phung T, Chakraborti T, Williams T, Szafir D. Virtual, augmented, and mixed reality for human-robot interaction: A survey and virtual design element taxonomy. J Hum-Robot Interact. 2023;12(4):1-39.[DOI]

-

14. Chadalavada RT, Andreasson H, Krug R, Lilienthal AJ. That’s on my mind! Robot to human intention communication through on-board projection on shared floor space. In: 2015 European Conference on Mobile Robots (ECMR); 2015 Sep 02-04; Lincoln, UK. Piscataway: IEEE; 2015. p. 1-6.[DOI]

-

15. Rosen E, Whitney D, Phillips E, Chien G, Tompkin J, Konidaris G, et al. Communicating and controlling robot arm motion intent through mixed-reality head-mounted displays. Int J Robot Res. 2019;38:1513-1526.[DOI]

-

16. Muhammad F, Hassan A, Cleaver A, Sinapov J. Creating a shared reality with robots. In: 2019 14th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI); 2019 Mar 11-14; Daegu, South Korea. Piscataway: IEEE; 2019. p. 614-615.[DOI]

-

17. Ikeda B, Szafir D. Advancing the design of visual debugging tools for roboticists. In: 2022 17th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI); 2022 Mar 07-10; Sapporo, Japan. Piscataway: IEEE; 2022. p. 195-204.[DOI]

-

18. Chang CT, Hayes B. A survey of augmented reality for human–robot collaboration. Machines. 2024;12(8):540.[DOI]

-

19. Suzuki R, Karim A, Xia T, Hedayati H, Marquardt N. Augmented reality and robotics: A survey and taxonomy for AR-enhanced human-robot interaction and robotic interfaces. In: Proceedings of the 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; 2022 Apr 29-May 05; New Orleans, USA. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2022. p. 1-33.[DOI]

-

20. Gruenefeld U, Prädel L, Illing J, Stratmann T, Drolshagen S, Pfingsthorn M. Mind the ARm: Realtime visualization of robot motion intent in head-mounted augmented reality. In: Proceedings of Mensch und Computer 2020; 2020 Sep 06-09; Magdeburg, Germany. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2020. p. 259-266.[DOI]

-

21. Sonawani S, Amor H. When and where are you going? A mixed-reality framework for human robot collaboration. In: 5th International Workshop on Virtual, Augmented, and Mixed Reality for HRI [Internet]. 2022 Mar. Available from: https://openreview.net/forum

-

22. Sonawani S, Zhou Y, Amor HB. Projecting robot intentions through visual cues: Static vs. Dynamic signaling. In: 2023 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS); 2023 Oct 01-05; Detroit, USA. Piscataway: IEEE; 2023. p. 7931-7938.[DOI]

-

23. Chadalavada RT, Andreasson H, Schindler M, Palm R, Lilienthal AJ. Bi-directional navigation intent communication using spatial augmented reality and eye-tracking glasses for improved safety in human–robot interaction. Robot Comput-Integr Manuf. 2020;61:101830.[DOI]

-

24. Dianatfar M, Latokartano J, Lanz M. Review on existing VR/AR solutions in human–robot collaboration. Procedia CIRP. 2021;97:407-411.[DOI]

-

25. Chacko SM, Granado A, RajKumar A, Kapila V. An augmented reality spatial referencing system for mobile robots. In: 2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS); Oct 24- Jan 24; Las Vegas, USA. Piscataway: IEEE; 2020. p. 4446-4452.[DOI]

-

26. Chacko SM, Granado A, Kapila V. An augmented reality framework for robotic tool-path teaching. Procedia CIRP. 2020;93:1218-1223.[DOI]

-

27. ARCore [Internet]. Mountain View: Google for Developers; c2025 [cited 2025 Dec 10]. Available from: https://developers.google.com/ar

-

28. Macenski S, Foote T, Gerkey B, Lalancette C, Woodall W. Robot Operating System 2: Design, architecture, and uses in the wild. Sci Robot. 2022;7(66):eabm6074.[DOI]

-

29. Gatsoulis Y, Virk GS, Dehghani-Sanij AA. On the measurement of situation awareness for effective human-robot interaction in teleoperated systems. J Cogn Eng Decis Mak. 2010;4(1):69-98.[DOI]

-

30. Sahin M, Subramanian K, Sahin F. Using augmented reality to enhance worker situational awareness in human robot interaction. In: 2024 IEEE Conference on Telepresence; 2024 Nov 16-17; Pasadena, USA. Piscataway: IEEE; 2024. p. 217-224.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite