Shanshan Chen, School of Materials Science and Engineering, Nankai University, Tianjin 300350, China. E-mail: sschen@nankai.edu.cn.

Abstract

Immobilized photocatalyst devices for overall water splitting (OWS) have emerged as a promising strategy for practical hydrogen production. Compared with traditional powder suspension systems, they offer great advantages, including scalability, facile recovery/replacement of photocatalysts, and the elimination of extra dispersion operations. Over the past decade, significant progress has been achieved in this field, especially in material screening, device construction, and system integration for scalable applications. However, up until now, there have been no related reviews focusing on this topic. This review aims to fill this gap by providing a comprehensive and structured overview of the immobilized photocatalyst devices for efficient OWS. Firstly, the basics of OWS process, including one-step and two-step photoexcitation mechanisms, are elaborated. Subsequently, recent advances in immobilized photocatalyst devices for scalable OWS via these two different approaches are summarized, based on which various solid-state electron mediators are classified and exemplified. The essential structure-performance relationship is also analyzed and revealed. Finally, the future prospects and challenges in this field are proposed and discussed.

Keywords

1. Introduction

Green hydrogen, as a multifunctional and sustainable energy carrier, is increasingly recognized as a key contributor in the global transition toward a low-carbon economy[1,2]. Photocatalytic overall water splitting (OWS) has garnered significant attention for its potential to produce green hydrogen from water utilizing solar energy[3-8]. This process represents an artificial photosynthesis reaction without any emission of CO2. Moreover, the produced green hydrogen can be further utilized for CO2 hydrogenation, thus contributing to CO2 reduction[9-12]. Typically, photocatalytic OWS can be achieved via two distinct ways: one-step and two-step photoexcitation routes[13,14]. For the one-step photoexcitation system, both the H2 evolution reaction (HER) and O2 evolution reaction (OER) occur on a single photocatalyst. It means the conduction band minimum (CBM) and valence band maximum (VBM) of the semiconductor photocatalyst should straddle the potentials of H+/H2 and H2O/O2, respectively. In addition, to maximize the theoretical solar-to-hydrogen (STH) conversion efficiency, the semiconductor’s absorption edge should be narrow enough to harvest more photons from sunlight. However, as the absorption edge increases, the corresponding redox driving force for water splitting decreases significantly, limiting the number of reported photocatalysts capable of achieving visible-light driven one-step photoexcitation OWS[15]. For the two-step photoexcitation system (commonly referred to as Z-scheme system), the HER and OER are performed over two different photocatalysts, leaving the residual electrons in the O2 evolution photocatalyst (OEP) and holes in the H2 evolution photocatalyst (HEP) “recombine” to form a closed cycle. In such case, the requirement of band structure of the applied photocatalysts is alleviated. Specifically, the HEP possesses a CBM more negative than the H+/H2 potential, while the OEP possesses a VBM more positive than the H2O/O2 potential[16]. Therefore, several narrow band gap semiconductors unsuitable for the one-step photoexcited approach can be employed in Z-scheme OWS systems[17-20]. Both ways expand the possibilities for solar-driven photocatalytic OWS process, contributing to rapid advances in this field and enabling the development of diverse photocatalyst systems with varying materials, routes, and efficiencies.

Besides the aforementioned materials and efficiencies, the existing form of the photocatalyst during the reaction is a critical factor for the future practical applications. Generally, the photocatalytic OWS is evaluated using powder photocatalyst suspended in an aqueous solution (commonly referred to as the powder suspension system)[21]. However, such system faces significant challenges for large-scale implementation, because it requires continuous stirring to maintain the uniform dispersion and is also difficult to recover/replace the photocatalyst[22]. To tackle those problems, an immobilized photocatalyst system is developed, in which the powder photocatalyst is fixed as a thin layer on a substrate, and the formed photocatalyst sheet structure is stable under various reaction conditions, such as stirring and the pH value[23]. Based on it, an integrated system featuring scalability, facile recovery/replacement of photocatalysts, and no extra operation for photocatalyst dispersion can be built (Figure 1), showing great potential for large-scale application of photocatalytic OWS[24].

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of the immobilized photocatalyst system for scalable OWS. OWS, overall water splitting.

Although immobilized photocatalyst systems for scalable OWS have only been explored for about a decade, significant progress has been achieved. To date, various immobilized photocatalyst systems have been developed, ranging from one-step photoexcitation route to Z-scheme approach mediated by metals, metal oxides, nonmetals, or biofilms[25-29]. Correspondingly, multiple large-scale fabrication techniques have been established, such as programmed spraying, screen printing, particle transfer method, and suction filtration method[30-32] (Figure 2). For example, Wang et al. reported an immobilized photocatalyst device with a size of 3 × 3 cm2 prepared via the particle transfer method that could deliver an STH conversion efficiency of 1.2% at 331 K and 10 kPa without external bias. In this device, a Z-scheme OWS system was constructed by employing Ru/Cr2O3-loaded La and Rh codoped SrTiO3 (SrTiO3:La,Rh), Mo doped BiVO4 (BiVO4:Mo), and C as an HEP, an OEP, and an electron mediator, respectively[28]. This efficiency is the highest among the reported particulate photocatalyst sheet systems for OWS. What’s more, a 100 m2 immobilized Al-doped SrTiO3 (SrTiO3:Al) device fabricated via the programmed controlled spraying achieved a peak STH conversion efficiency of 0.76% under natural sunlight and operated safely for more than one year, providing a practical reference for the large-scale applications of such devices[30]. These progresses underscore the critical role of immobilized photocatalyst devices in advancing the OWS research from laboratory prototype to large-scale demonstration, demonstrating the great potential for future practical applications. However, to the best of our knowledge, no specific review has yet systematically addressed immobilized photocatalyst devices for scalable OWS for green hydrogen production.

Figure 2. Schematic diagram of the classified illustration content for the immobilized photocatalyst devices towards OWS. OWS: overall water splitting.

To fill this gap and provide a systematic overview of immobilized photocatalyst devices for efficient OWS, this review is therefore prepared. Firstly, the basics of the photocatalytic OWS process are introduced. Then, why the immobilized photocatalyst devices need to be developed is answered. Subsequently, the key advances in such devices for scalable OWS are classified and illustrated. Finally, the conclusion and future prospects in this evolving field are proposed. It is hoped that this review can motivate more researchers across interdisciplinary fields to advance the development of efficient and scalable photocatalytic OWS systems and offer valuable guidance for their practical applications.

2. Basics of Photocatalytic OWS

2.1 Photocatalytic OWS reaction process and evaluation

As a thermodynamically unfavorable process, the OWS reaction demands an external energy input to overcome the intrinsic energy barrier (Equation 1)[33].

When the CBM is more positive than the H+/H2 reduction potential (-0.41 V vs. NHE at pH = 7) and the VBM is more negative than the H2O/O2 oxidation potential (0.82 V vs. NHE at pH = 7), the photogenerated electrons can reduce H+ to produce H2, while holes can oxidize H2O to produce O2. Therefore, semiconductors with bandgaps larger than 1.23 eV that can straddle the H+/H2 and H2O/O2 redox potentials are thermodynamically capable of driving the one-step photoexcited OWS process (Figure 3a). The light absorption wavelength range of the photocatalyst determines the maximum theoretical limit of STH conversion efficiency. It means the semiconductor bandgap should be as narrow as possible while still satisfying the thermodynamic requirements for water splitting. However, narrowing the bandgap generally compromises the redox ability and escalates the chance of electron-hole recombination[34].

Figure 3. Schematic energy diagrams corresponding to various categories of photocatalytic OWS systems. (a) One-step photoexcitation; (b) Two-step photoexcitation employing an aqueous redox mediator; (c) Two-step photoexcitation employing a solid-state electron mediator. OWS: overall water splitting; CBM: conduction band minimum; VBM: valence band maximum; Eg: bandgap energy; HEP: H2 evolution photocatalyst; OEP: O2 evolution photocatalyst; NHE: normal hydrogen electrode; Ox: oxidant; Red: reductant.

Inspired by the natural photosynthesis process in the plant, two-step photoexcited OWS aims to mimic natural photosynthesis, primarily comprising an HEP and an OEP[35]. The Z-scheme system alleviates the stringent band structure requirements for photocatalysts, as it only requires that the HEP possess a CBM more negative than the H+/H2 potential, and the OEP own a VBM more positive than the H2O/O2 potential. In this system, H+ is reduced to H2 at the HEP, while H2O is oxidized to O2 at the OEP, leaving the photoexcited holes in the HEP and electrons in the OEP to recombine via an aqueous redox mediator or a solid-state electron mediator to complete the whole reaction cycle[36] (Figure 3b,c).

In a Z-scheme OWS system, aqueous redox mediators are widely employed to facilitate electron transfer between the OEP and the HEP[37]. Generally speaking, to facilitate efficient reduction and oxidation processes, the redox potential of the oxidant/reductant must lie between the H+/H2 and H2O/O2 potentials. Numerous aqueous redox couples have been successfully implemented in Z-scheme OWS systems, including IO3-/I-, I3-/I-, Fe3+/Fe2+, [Co(bpy)3]3+/[Co(bpy)3]2+, [Co(phen)3]3+/[Co(phen)3]2+, and [Fe(CN)6]3-/[Fe(CN)6]4-[38-42]. Alternatively, electrons can be transferred between the OEP and the HEP through solid-state electron mediators. As early as 2006, Tada et al. reported a Z-scheme system using a three-component CdS-Au-TiO2, where Au nanoparticles served as the recombination channel of electrons from TiO2 and holes from CdS[43]. Since then, several electron conductors, such as Ag, Au, Rh, Ni, C, indium-doped tin oxide (ITO), reduced graphene oxide (rGO), and carbon nanotube (CNT), have been identified as effective solid-state electron mediators for Z-scheme OWS systems[26-28].

To enable a fair comparison of photocatalytic OWS performance reported by different groups, the STH conversion efficiency and apparent quantum efficiency (AQE) have been introduced and widely adopted as activity indexes[44-46]. Specifically, the STH conversion efficiency is defined as the ratio of the chemical energy stored in hydrogen to the energy supplied by the incident solar light, as described in Equation 2:

where

The AQE, on the other hand, is generally defined as the ratio of the number of photons utilized in the OWS reaction to the number of incident photons at a specific wavelength. Its calculation follows Equation 3:

where A, R, Na, and I denote constant, H2 or O2 evolution rate during the photocatalytic OWS reaction, the Avogadro constant and the incident photons, respectively. Herein, the values of A for H2 and O2 evolution are 2 and 4 in a one-step photoexcited OWS process, while 4 and 8 in a Z-scheme OWS approach, respectively.

2.2 Comparison of the powder suspension system and the immobilized photocatalyst system

Generally, the powder suspension form is applied for the particulate photocatalysts to evaluate photocatalytic OWS performance[47]. In this case, the introduced powder photocatalyst is well-dispersed in the reaction solution, ensuring maximal light absorption and sufficient contact with the aqueous solution, which facilitates the screening and optimization of new photocatalysts. Consequently, this form is widely adopted at a laboratory scale for fundamental research[48]. However, maintaining a stable dispersion of photocatalyst particles requires continuous mechanical stirring or circulation, which consumes external energy and becomes increasingly impractical as the reactor size increases[49]. Moreover, the recovery and reuse of particulate photocatalysts from suspensions are challenging, as particles tend to aggregate or settle, resulting in photocatalyst loss and increased operational complexity and nondeterminacy[50-52].

Immobilizing photocatalysts on designated substrates can effectively overcome the aforementioned issues. In such immobilized systems, stirring or circulation is no longer required to maintain the powder suspension, thereby reducing operational energy consumption and simplifying the reactor design for large-scale deployment[53]. Furthermore, the immobilized system ensures the efficient reuse of photocatalysts without the risk of aggregation or loss, addressing the recyclability challenge inherent to powder suspension system[54]. The robust physical contact among photocatalysts, the solid-state electron mediator and the substrate can also enhance the Z-scheme OWS process and the mechanical stability of the integrated system, enabling sustained long-term outdoor operation, which is crucial for practical applications[55]. Compared with the powder suspension system, the immobilized photocatalyst system is more desirable for future industrial-scale implementation. Consequently, it is primarily focused in this review, and its key progress in photocatalytic OWS is summarized and elaborated in the following section. A detailed comparison between the powder suspension system and the immobilized photocatalyst system is provided in Table 1.

| Feature | Powder suspension system | Immobilized photocatalyst system |

| System configuration | Photocatalysts are dispersed in a reaction solution | Photocatalysts are immobilized on the designated substrates |

| Light harvesting | Sufficient light harvesting | Light harvesting is highly dependent on the thickness of the photocatalyst layer |

| Operational energy | Additional energy is needed for photocatalysts dispersion in the suspension | No energy is needed for stirring or dispersing the photocatalysts |

| Catalyst recovery and reuse | Difficult | Convenient |

| Scalability and practicality | Impractical for large-scale demonstration, but suitable for lab-scale fundamental research | Easy to be scaled, and suitable for practical application in a large scale |

3. Progress of Photocatalytic OWS over the Immobilized Photocatalyst Systems

For the construction of immobilized photocatalyst devices, one-step photoexcitation systems are typically fabricated using a drop-casting process. In contrast, two-step photoexcitation systems generally require the solid-state electron mediator to effectively “link” the HEP and the OEP, consequently deriving various markedly different manufacturing processes[56]. Therefore, this section will systematically review the recent advances in immobilized photocatalyst systems based on their different reaction approaches, photocatalysts, and preparation methods.

3.1 Immobilized photocatalyst systems in a one-step photoexcited approach

In the one-step photoexcitation approach, the OWS reaction takes place on a single photocatalyst. When it is immobilized into a device, challenges associated with photocatalyst dispersion, cocatalyst detachment during the mechanical stirring, photocatalyst recovery/replacement and the scalability can be effectively mitigated compared with powder suspension system[24]. This section will introduce and analyze the progress and functions of such immobilized devices, providing insights for the design of efficient devices, with the aim of further deepening the understanding of the relationship between device structure and large-scale photocatalytic performance.

The primary challenge in fabricating devices by immobilizing powder photocatalysts on substrates lies in the dense accumulation of particulate photocatalysts, which hinders efficient mass and gas transfer processes. Xiong et al. addressed this issue by incorporating inert SiO2 particles to disperse the applied Rh2-xCrxO3-modified (Ga1–xZnx)(N1–xOx) photocatalyst[57]. The resulting composite was deposited onto a 5 × 5 cm2 glass plate via a drop-casting method, forming an immobilized photocatalyst device for one-step photoexcited OWS. Notably, the inclusion of hydrophilic SiO2 particles with different sizes can significantly improve the porosity and hydrophilicity of the photocatalyst layer, thereby facilitating the mass transfer of water and gases and yielding photocatalytic activity comparable to that of the powder suspension system (Figure 4a). Meanwhile, the fabrication process of the device is simple, scalable, and flexible to diverse substrates, showing considerable potential for large-scale applications.

Building on the above result of SiO2-mediated mass and gas transfer, Goto et al. have further developed a scalable OWS device[25]. A demo with a size of 1 × 1 m2 was fabricated using RhCrOx-modified SrTiO3:Al photocatalyst, comprising an array of nine photocatalyst sheets, each with dimensions of 33 × 33 cm2 (Figure 4b,c). A suspension containing particulate photocatalyst, SiO2 nanoparticles, and binder was deposited onto glass substrates via a drop-casting process, forming a particle layer with a thickness of 10-20 μm. The device employs transparent acrylic plates as the window material and is entirely tilted at 10° to facilitate the release of gas bubbles through buoyancy. A 4 mm thin water layer is designed to minimize water pressure. Under natural sunlight irradiation (65-75 mW cm-2), the system achieved an STH conversion efficiency of approximately 0.4%, representing the highest efficiency for photocatalytic OWS at the square-meter scale at that time. The system eliminates the need for forced convection and utilizes hydrophilic window materials to prevent bubble accumulation, providing a feasible device design scheme for large-scale OWS and introducing a comprehensive system concept including gas-liquid separation.

Based on the above-mentioned experience in 1 m2 of system, a 100 m2 of OWS system was further designed and ultimately assembled in 2021, which is the largest in area ever reported[30]. This achievement demonstrated its large-scale feasibility, with the design emphasizing operability, safety, and efficiency. The system comprises 1,600 panel reactor units (each with an area of 625 cm2), tilted at 30° to maximize light reception (Figure 5a). Each reactor features an ultraviolet-transparent glass window and a polycarbonate housing, with a 0.1 mm water layer between glass and photocatalyst sheet to reduce the load and prevent oxyhydrogen accumulation (Figure 5b). Supported by aluminum brackets, units use polyurethane tubes with different inner diameters for the corresponding transport of gas and water. The photocatalyst sheet is composed of SiO2 nanoparticles, calcium chloride, and the photocatalyst of SrTiO3:Al loaded with Rh/Cr2O3 and CoOx cocatalysts, uniformly prepared via programmed spraying. Frosted glass serves as the substrate of the photocatalyst sheet to ensure wettability and mechanical strength. However, long-term outdoor operation, particularly in winter, can cause the photocatalytic particle layer to peel off due to repeated freezing and thawing of water within the panel reactors. Efficient separation of H2 from O2 is achieved using a commercial polyimide hollow fiber membrane, with a transmembrane pressure difference generated by a vacuum pump serving as the driving force. The high selectivity, stemming from the permeation rate of H2 being ten times that of O2, enables H2 production with a purity greater than 94% and a recovery rate of 73%. This membrane technique surpasses alternative separation methods in energy efficiency and operational simplicity, making it suitable for outdoor, large-scale applications. But the current membrane is not specifically designed for H2-O2 separation. It is necessary to develop membranes with higher H2 permeability and lower O2 permeability, and optimize the gas-handling processes to reduce the energy consumption and equipment cost. Over more than a year of operation, the system achieves a maximum STH conversion efficiency of 0.76%. This value represents a peak under optimized conditions, and the system continues to face severe challenges during long-term operation. Comprising 1,600 reactor units, the system involves regular replacement of photocatalyst sheets, a maintenance process that remains cumbersome. Despite the current low efficiency and energy negative balance, the accumulation in module design, system assembly, and operational experience can benefit the development of practical, large-scale OWS systems (Figure 5c).

Figure 5. (a) The image of a panel reactor unit with 625 cm2; (b) Side-view of the structure of the panel reactor unit; (c) An overhead view of the 100 m2 solar H2 production system consisting of 1,600 panel reactor units and a hut housing a gas separation facility (indicated by the yellow box). Republished with permission from[30]; (d) Synergetic effect mechanism of promoting the forward H2 and O2 evolution reactions while inhibiting the reverse H2-O2 recombination in the photocatalytic OWS; (e) A 4 × 4 cm2 Rh/Cr2O3/Co3O4-loaded InGaN/GaN nanowire wafer under the illumination of the concentrated natural solar light. Republished with permission from[58]. OWS: overall water splitting.

In addition to applications under natural sunlight, concentrated sunlight is also considered, in which the utilization of infrared light and its thermal effect can be further modulated to enhance the STH conversion efficiency. For instance, Zhou et al. synthesized an InGaN/GaN nanowire (NW) photocatalyst thin film with high crystallinity and a well-aligned structure on commercial silicon wafers via molecular-beam epitaxy[58]. Due to the variation of In content along the growth direction, InGaN/GaN NWs exhibit a multi-band structure, enabling a broad visible-light response range (400-700 nm)[59,60]. Furthermore, a temperature-dependent strategy was implemented in this study. The device incorporates a heat-insulating layer to heat the reaction system to an optimal temperature of approximately 70 °C by harvesting the previously wasted infrared light (Figure 5d). This temperature enhances mass transfer and activates chemical bonds, promoting the forward HER and OER while inhibiting reverse H2-O2 recombination. Under the optimized conditions, the system achieves an STH conversion efficiency of 9.2% in pure water under concentrated simulated solar light. A scaled-up 4 × 4 cm2 test achieves an STH value of 6.2% under natural sunlight, confirming the operational feasibility (Figure 5e). This study has successfully addressed the efficiency bottlenecks of photocatalytic OWS. Nevertheless, the validation of this strategy is currently restricted to small-sized photocatalyst devices, and the performance under large-scale application scenarios still requires further exploration. To provide a brief summary of these studies, the aforementioned representative one-step photoexcited OWS devices are summarized in Table 2.

| Photocatalyst | Cocatalyst | Devicearea | Efficiency | Refs |

| (Ga1‒xZnx)(N1‒xOx) | Rh2‒yCryO3 | 25 cm2 | – | [57] |

| SrTiO3:Al | RhCrOₓ | 1 m2 | STH: 0.4% (101 kPa, 298 K) | [25] |

| SrTiO3:Al | Rh2‒yCryO3-CoOx | 100 m2 | STH: 0.76% | [30] |

| InGaN/GaN nanowires | Rh/Cr2O3-Co3O4 | 0.64 cm2 | STH: 9.2% (68.4 kPa, 343 K) | [58] |

STH: solar to hydrogen; OWS: overall water splitting.

3.2 Immobilized photocatalyst systems in a Z-scheme approach

Unlike the one-step photoexcitation approach that only needs a single photocatalyst, the Z-scheme route typically involves an HEP, an OEP and a solid-state electron mediator. In an immobilized photocatalyst system, the electron mediator should maintain intimate contact with the HEP and the OEP while avoiding the light absorption of photocatalysts[61]. To date, various Z-scheme OWS systems have been developed, along with the corresponding immobilization methods. In this section, the research progress of the immobilized photocatalyst devices in a Z-scheme approach is outlined, including device design and performance characteristics using different types of solid-state electron mediators, such as metals, metal oxides, non-metals, and biofilms.

3.2.1 Metal as a solid-state electron mediator

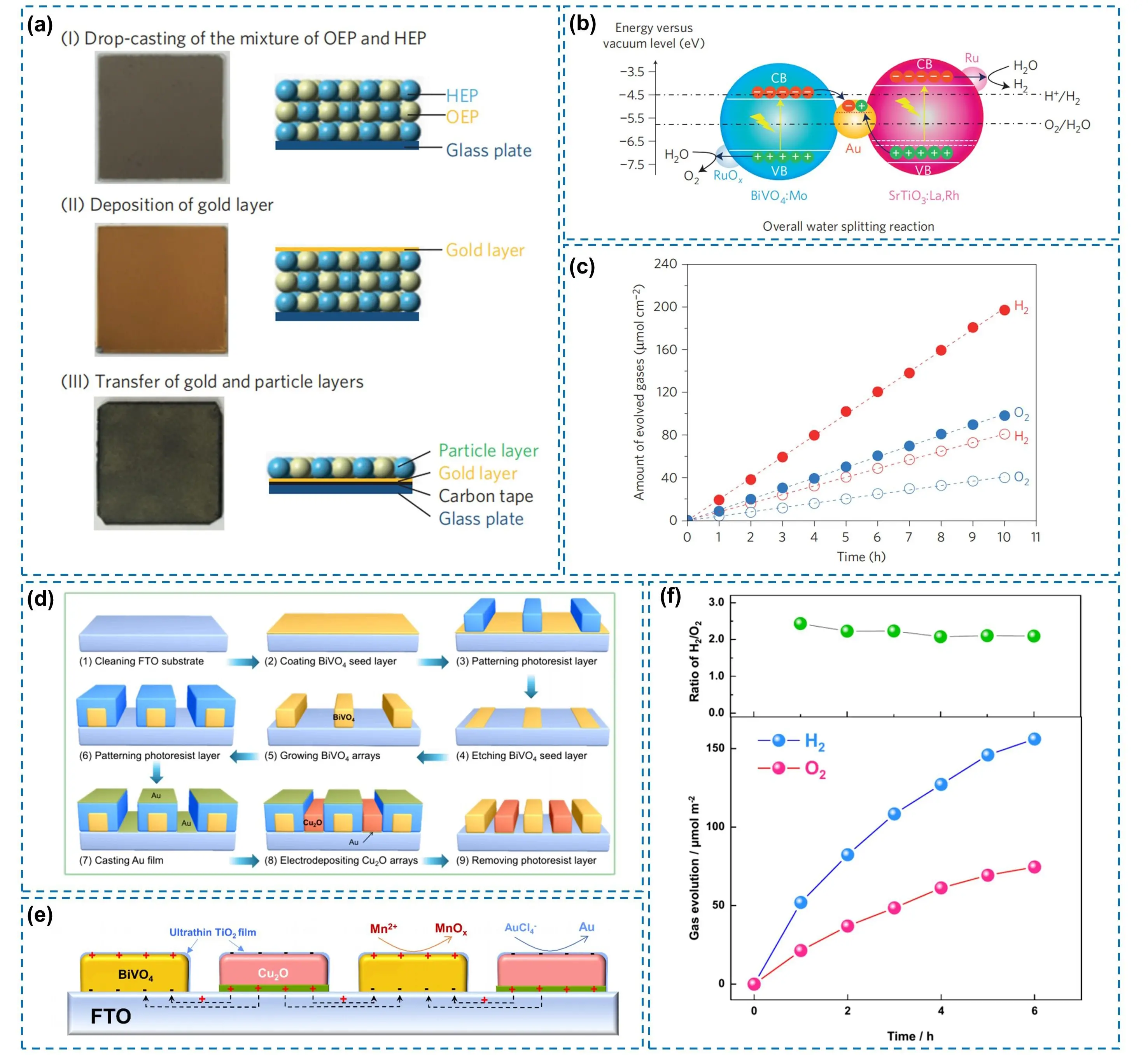

Metals are firstly used as the solid-state electron mediators in Z-scheme OWS systems, playing a critical role in facilitating electron transfer from an OEP to an HEP. In 2015, Wang et al. first fabricated an immobilized photocatalyst device with an area of 9 cm2 via the particle transfer method, where SrTiO3:La,Rh and BiVO4 functioned as the HEP and OEP, respectively, and an Au layer acted as the solid-state electron mediator[26]. In this system, the Au layer facilitates the charge transfer between the HEP and the OEP. The photocatalytic water splitting activity of this device was 6 and 20 times higher than those of the HEP/OEP systems in powder suspension form and without a metal layer, respectively.

Subsequently, building upon this research, Wang et al. further optimized several aspects, including the photocatalyst composition and the design and preparation of the Au layer, to achieve superior performance (Figure 6a)[31]. The optimized device consists of SrTiO3:La,Rh, BiVO4:Mo, and an Au layer (Figure 6b). Meanwhile, a Cr2O3 layer photodeposited on Ru cocatalyst-modified SrTiO3:La,Rh can effectively suppress the reverse reaction of H2-O2 recombination. Additionally, annealing at 573 K for 20 min can reduce the contact resistance between the semiconductors and the Au layer, thereby enhancing electron transfer efficiency. As a result, the device achieves an STH conversion efficiency of 1.1% and an AQE of 33% at 419 nm. It represents the highest performance to date for Z-scheme OWS devices using SrTiO3. However, its activity was significantly affected by the operating pressure. When the background pressure increased from 5 kPa to 10 kPa, the photocatalytic activity decreased to 23%. This decline is attributed to the fact that at higher pressure, H2 and O2 bubbles require a larger number of gas molecules to desorb from the surface of the photocatalyst sheet, and simultaneously, uninhibited backward reactions further contribute to the activity loss (Figure 6c). Although the particle transfer method faces challenges for large-scale manufacturing, this study provides a valuable technical reference for optimizing process parameters in large-scale devices.

Figure 6. (a) Schematic diagram of the preparation steps for the SrTiO3:La,Rh/Au/BiVO4:Mo device via the particle transfer method; (b) Schematic diagram of OWS over the Ru-SrTiO3:La,Rh/Au/BiVO4:Mo device; (c) Time courses of the OWS reaction over a Cr2O3/Ru-SrTiO3:La,Rh/Au/BiVO4:Mo device under simulated sunlight (AM 1.5G) at 288 K and 5 kPa (open markers) and 331 K and 10 kPa (closed markers). Republished with permission from[31]; (d) Schematic representation of fabricating alternate BiVO4 and Au:Cu2O strips with fixed interspace on FTO(BiVO4||Au:Cu2O@FTO); (e) Sketch map of photogenerated charge carriers (electrons and holes) between strips in the integrated system; (f) Photocatalytic activity of OWS over the patterned sheet (3 cm × 3 cm) deposited with Pt cocatalyst under visible light. Republished with permission from[69]. HEP: H2 evolution photocatalyst; OEP: O2 evolution photocatalyst; CB: conduction band; VB: valence band; OWS: overall water splitting; FTO: fluorine-doped tin oxide.

Based on the aforesaid prototype of SrTiO3:La,Rh/Au/BiVO4:Mo device, this study has extended beyond metal oxide photocatalysts to explore other types of narrow bandgap photocatalysts, thereby broadening the utilized wavelength of the incident light. For example, a series of metal oxynitrides (e.g., LaMg1/3Ta2/3O2N), metal oxysulfides (e.g., La5Ti2Cu0.9Ag0.1O7S5) and metal selenides (e.g., (ZnSe)0.5(CuGa2.5Se4.25)0.5) have been successfully applied in the immobilized photocatalyst devices, some of which even have absorption edges as long as 700 nm, demonstrating the great potential of such device for efficient Z-scheme OWS[62-67].

In traditional Z-scheme systems, the disordered distribution between an OEP and an HEP tends to form a Type-II charge transfer pathway, reducing the utilization efficiency of charge carriers[68]. To address this issue, Zhen et al. developed a patterned “artificial leaf”[69]. By employing the photolithography technique to construct alternating strips of the OEP (BiVO4) and the HEP (Au-supported Cu2O, denoted as Au:Cu2O) (Figure 6d), coupled with an ultrathin TiO2 layer on the top surface, the unidirectional Z-scheme charge transfer is achieved (Figure 6e). This design eliminates competing charge transfer pathways by spatially separating active units, enabling stable production of H2 and O2 in pure water under visible light irradiation, with a near stoichiometric ratio of 2:1. The respective evolution rates for H2 and O2 are 156 and 74 μmol·m-2, (Figure 6f). This work validates the efficacy of the patterned design, which can be scaled up via mature micro/nanofabrication techniques such as photolithography, providing a new paradigm for the development of next-generation, highly efficient Z-scheme OWS devices.

In addition to Au, some other metals with varying work functions, such as Ni and Rh, have also been identified as solid-state electron mediators in the SrTiO3:La,Rh/Au/BiVO4:Mo prototype device[26]. Results indicate that the case of Rh layer exhibits an activity even comparable to that of the Au layer, while the case of Ni layer shows lower activity, partly due to the corrosion during the reaction. At present, the effect of metal layer’s work function cannot be determined unambiguously, as its chemical stability under the reaction condition varies. Further study is still needed to elucidate the mechanism by which electrons can efficiently migrate across Schottky barriers.

3.2.2 Metal oxide as a solid-state electron mediator

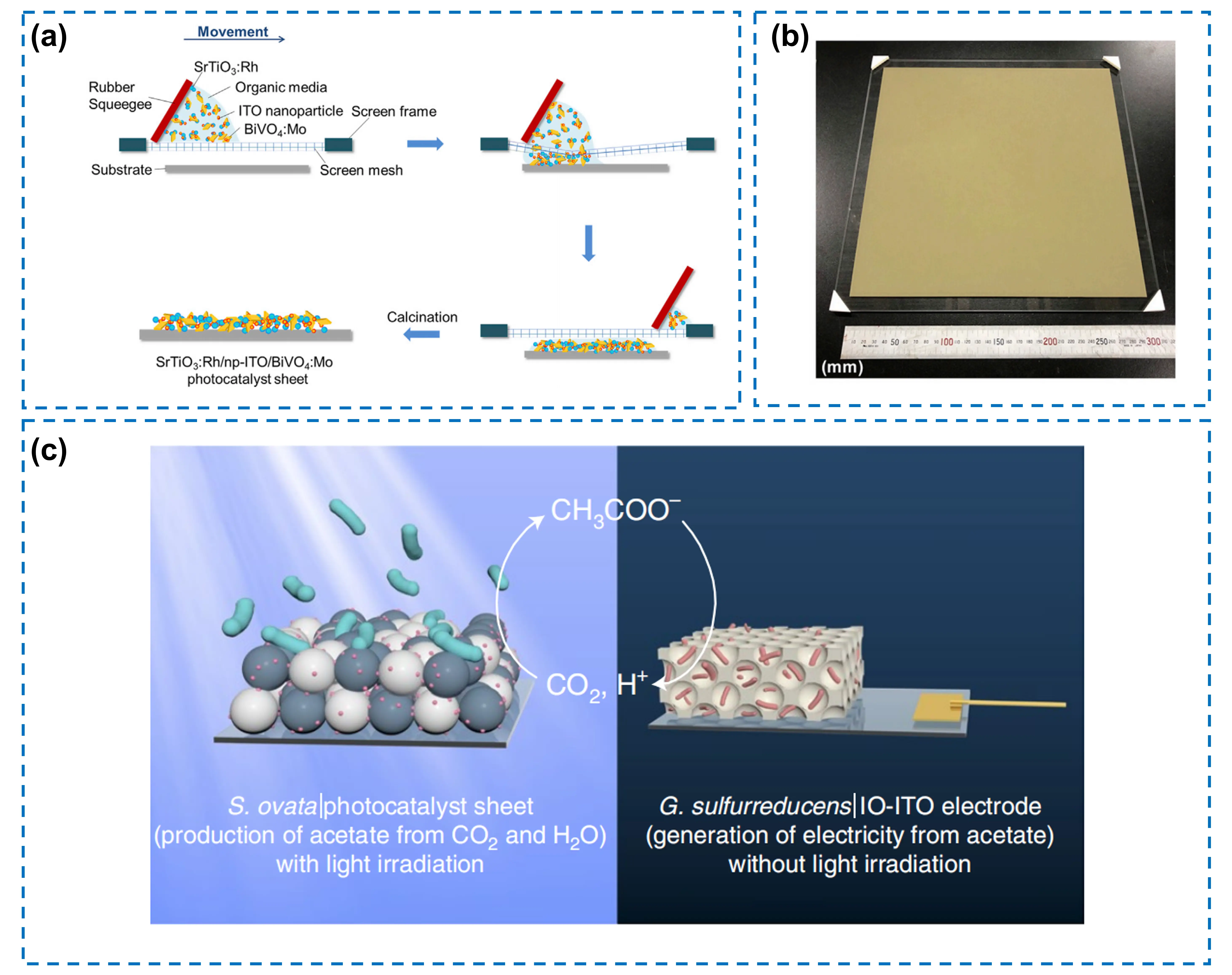

When metals are applied as electron mediators in Z-scheme OWS, their possible shortcomings, such as high cost, relatively high oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) activity, and poor chemical stability during the photocatalytic reaction, restrict their broader application. Metal oxide offers a promising alternative as solid-state electron mediators. Compared with metal, it is cost-effective, and shows low ORR activity and high chemical stability, rendering it more suitable for practical OWS devices. For instance, ITO has a transmittance of 56%-81% in the 420-540 nm wavelength range and much lower ORR activity than that of Au, which can reduce optical absorption loss and prohibit the side reaction. Based on this, Wang et al. developed an immobilized photocatalyst device prepared in the screen printing route. The device consists of Cr2O3/Ru-modified Rh-doped SrTiO3 (SrTiO3:Rh) as an HEP, RuO2-BiVO4:Mo as an OEP, and ITO as a solid-state electron mediator[27]. Such preparation route, which does not require vacuum conditions, allows the direct fabrication of a device with an area of 30 × 30 cm2 (Figure 7a,b). This system achieves an STH conversion efficiency of 0.4% and can realize stable OWS process at 5-95 kPa. Furthermore, this device can be integrated with the acetogenic bacterium Sporomusa ovata to form a bio-abiotic hybrid system. In this system, the evolved H2 and the photogenerated electrons can be directly utilized to drive selective CO2 reduction to acetate, achieving a solar-to-acetate efficiency of 0.7% without the need for organic additives[70]. The transparency of the ITO layer enables it to simultaneously harvest light for both water splitting and bacterial metabolism, while its high chemical stability prevents interference with microbial activity. This integration demonstrates a scalable pathway for closed-loop carbon conversion, where solar-generated acetate is directly used for electricity generation in bioelectrochemical systems, marking a transition from isolated photocatalysis to integrated, sustainable energy cycles (Figure 7c).

Figure 7. (a) Illustration of the preparation steps for a SrTiO3:Rh/np-ITO/BiVO4:Mo device via the screen printing method; (b) Photograph of a printed SrTiO3:Rh/np-ITO/BiVO4:Mo device with a size of 30 × 30 cm2. Republished with permission from[27]. (c) Schematic diagram illustrating that the sunlight-driven S.ovata|Cr2O3/Ru-SrTiO3:La,Rh|ITO|RuO2-BiVO4:Mo hybrid supplies CH3COO– ions to a biohybrid electrochemical system to generate current and close the carbon cycle. Republished with permission from[70]. IO: inverse opal; ITO: indium-doped tin oxide.

Similar to ITO, In@InOx has also been successfully applied as a solid-state electron mediator to link SrTiO3:Rh and BiVO4:Mo photocatalysts[71]. It is demonstrated that besides functioning as a charge conductor, In@InOx can act as a particle binder to maintain the structural stability of the device. The presence of InOx can suppress the ORR, thus enhancing photocatalytic performance.

3.2.3 Non-metal as a solid-state electron mediator

Besides metals and metal oxides, non-metals can also serve as effective solid-state electron mediators due to their good electron conductivity and relatively low ORR activity. Among non-metals, carbon has been extensively investigated because of its earth-abundant nature and low cost. For example, Wang et al. developed an immobilized photocatalyst device based on a carbon conductor layer (SrTiO3:La,Rh/C/BiVO4:Mo) for efficient Z-scheme OWS[28]. This device achieves an STH conversion efficiency of 1.2% at 331 K under a background pressure of 10 kPa. At near atmospheric pressure (91 kPa), the STH conversion efficiency is maintained at around 1.0%. This demonstrates that the carbon-based photocatalytic device can efficiently operate under the ambient condition, offering an economically viable strategy for the design of practical photocatalytic OWS systems.

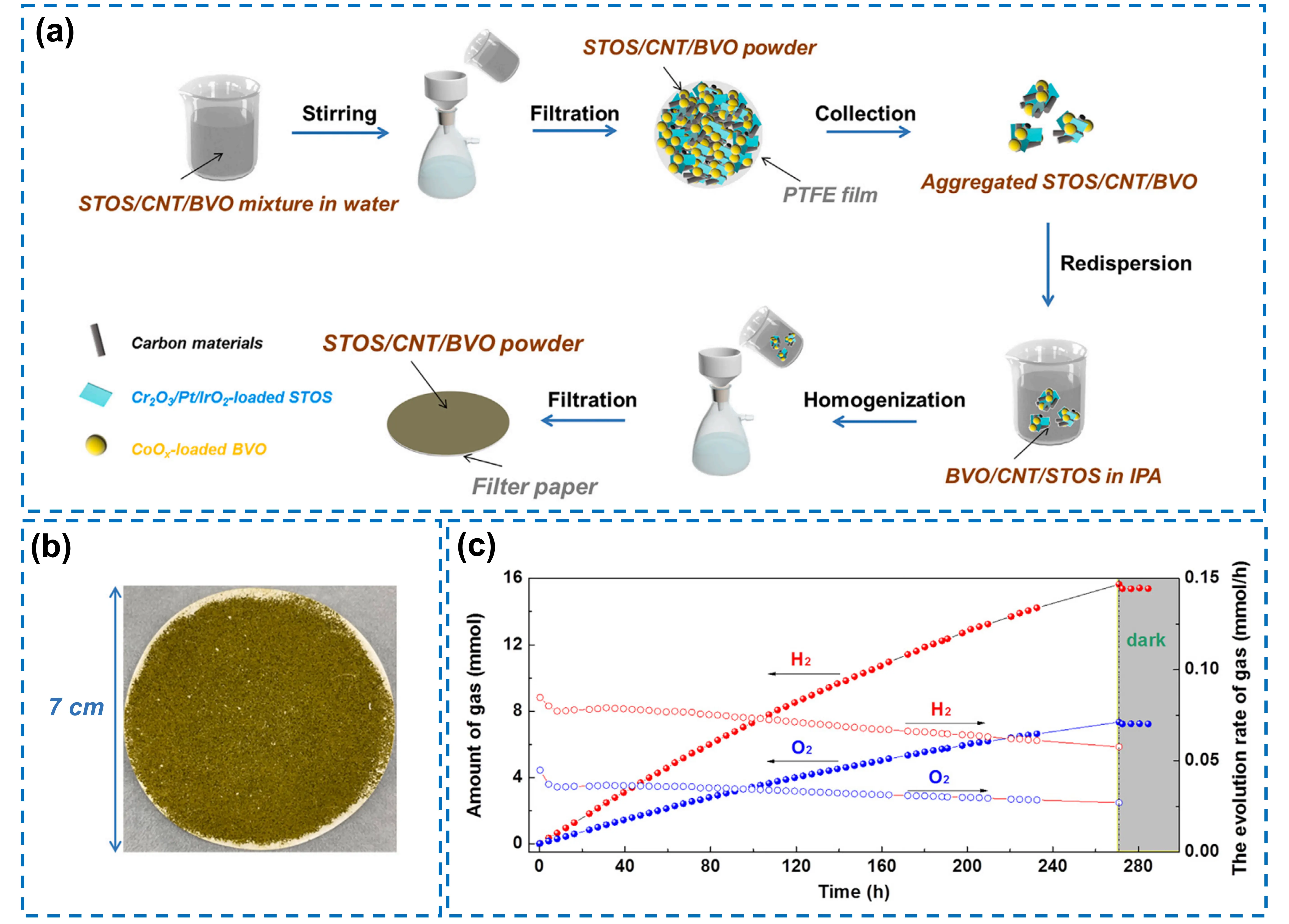

In addition, carbon-derived materials such as rGO and CNT have also been proven effective as solid-state electron mediators. In 2025, Gu et al. developed an immobilized photocatalyst device, where Sm2Ti2O5S2 and BiVO4 particles were interconnected by rGO or CNT to mediate the interfacial charge transfer[32]. However, unlike two-dimensional rGO, CNT does not excessively wrap photocatalysts or block their active sites; so the device using CNT exhibits superior performance. Notably, this device is fabricated via a simple filtration process (Figure 8a). This approach eliminates the need for vacuum/high-temperature processes or organic media, offering low-cost and straightforward operation. Moreover, large-scale production can be readily achieved through repeated filtration or redispersion, enabling the device to be scaled up to large dimensions (verified device with a diameter of 7 cm) (Figure 8b). The system achieves an STH conversion efficiency of 0.4% at 323 K and 10 kPa, operates stably at near atmospheric pressure (1 bar), and continuously produces H2 and O2 for 270 h without noticeable attenuation (Figure 8c).

Figure 8. (a) Schematic diagram of the fabrication procedures for a Sm2Ti2O5S2/CNT/BiVO4 device via a facile filtration method; (b) A photo of the device with a diameter of 7 cm; (c) Time courses of the evolved H2 and O2 gases and their evolution rates over the Sm2Ti2O5S2/CNT/BiVO4 device irradiated with visible light (λ > 420 nm) at 288 K under an initial pressure of 5 kPa. Republished with permission from[32]. STOS: Sm2Ti2O5S2; CNT: carbon nanotube; BVO: BiVO4; IPA: isopropanol.

3.2.4 Biofilm as a solid-state electron mediator

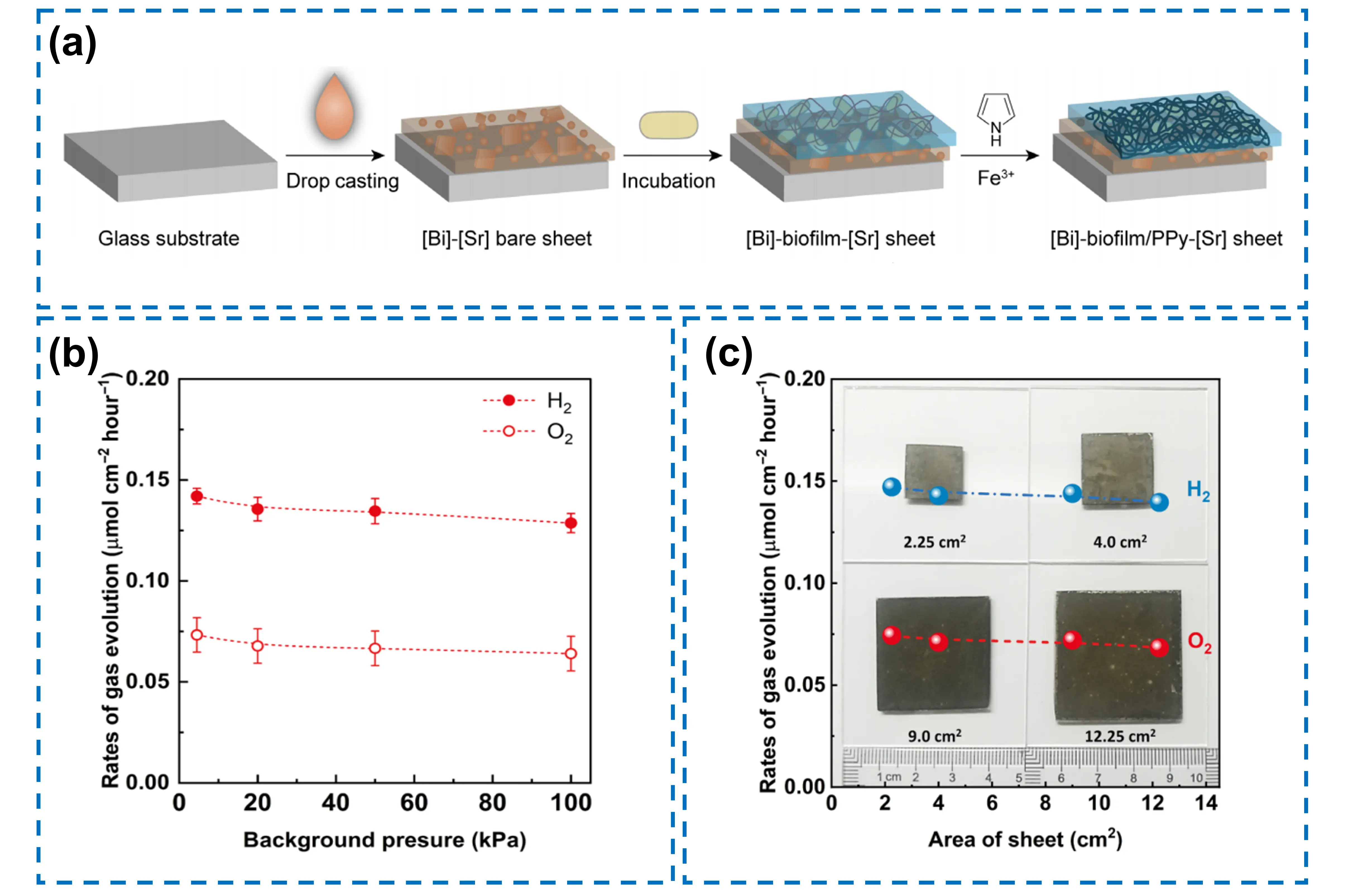

Biofilms have recently been verified to be feasible for solid-state electron mediators. More importantly, their inherent capabilities for self-regeneration and environmental responsiveness can avoid the frequent maintenance of the constructed device and endow it with long-term operational stability. For instance, Wang et al. developed a sustainable hybrid Z-scheme device for visible-light-driven OWS by integrating inorganic photocatalysts with conductive bacterial biofilms[29]. The device employs Cr2O3/Ru/SrTiO3:Rh as an HEP and CoOx/BiVO4:Mo as an OEP. It is fabricated by drop casting a mixture of photocatalysts onto a glass plate, followed by biofilm growth that forms a conformal conductive layer through oxidative polymerization of pyrrole molecules (Figure 9a). It enables the release of H2 and O2 at a stoichiometric ratio of 2:1. Owing to the self-regenerative property of biofilms and the chemical stability of polypyrrole, the device exhibits less than 10% efficiency loss after 100 h of the reaction. Additionally, it shows excellent resistance to pressure variations, retaining 91% of its activity when the background pressure is enhanced from 4.5 to 100 kPa (Figure 9b). Importantly, biofilms can be prepared on a large scale through simple cultivation, and devices with different areas (2.25-12.25 cm2) show a standard deviation of only 2.4% in performance (Figure 9c). The process does not require sophisticated equipment such as vacuum evaporation, making it suitable for scalable production.

Figure 9. (a) Illustration of the fabrication procedures for the [Bi]-biofilm/PPy-[Sr] device on a glass substrate preceding its transfer to another substrate; (b) Effect of background pressure on H2 and O2 evolution rates for the [Bi]-biofilm/PPy-[Sr] photocatalyst device; (c) Gas evolution rates for [Bi]-biofilm/PPy-[Sr] devices with different areas[29]. [Bi]: CoOx-BiVO4:Mo; [Sr]: Ru@Cr2O3-SrTiO3:Rh; PPy: polypyrrole.

Among the discussed electron mediators, noble metal mediators offer high charge transfer efficiency in Z-scheme OWS systems but are hampered by distinct drawbacks, such as high cost, pressure sensitivity, and susceptibility to side reactions like the ORR. Metal oxides present a more balanced alternative, with moderate cost, superior stability under ambient conditions, and relatively low ORR activity. However, their higher interfacial resistance limits charge transfer efficiency. Non-metals possess attractive features like low cost and low ORR activity, yet their performance strongly depends on the degree of integration between the photocatalyst particles and the non-metal mediator. Biofilms, although attractive for several advantages such as self-regeneration and simple preparation, demonstrate lower charge transfer efficiency and are prone to deactivation under high temperatures or extreme pH conditions. Therefore, the selection of a proper electron mediator for effective photocatalytic Z-scheme OWS will necessarily be a compromise.

3.2.5 Free of solid-state electron mediator

Beyond the systems described above that utilize metallic or non-metallic media, a special case exists in which the interfacial charge transfer between HEP and OEP occurs directly through physical contact, without the use of a solid-state electron mediator. Sasaki et al. reported a mediator-free Z-scheme OWS system comprising SrTiO3:Rh and BiVO4 photocatalysts[72]. In this system, direct contact is achieved through powder aggregation under acidic conditions, allowing interparticle electrons to transfer from the CBM of BiVO4 to the Rh3+/Rh4+ redox level in SrTiO3:Rh, thereby ensuring efficient charge transfer. Based on this result, they further developed BiVO4–SrTiO3:Rh composite photocatalysts, where SrTiO3:Rh particles attached to BiVO4 particles[73]. Such composite photocatalysts can realize effective interparticle electron transfer without adjusting the pH value of the reaction solution, enabling pure water splitting with an AQE of 1.6% at 420 nm. These series works collectively provide a new strategy for constructing the immobilized photocatalyst device in a Z-scheme approach for OWS, avoiding potential drawbacks associated with electron mediators during the reaction, such as light-blocking effects and competitive occupation of active sites.

In this section, recent advances in immobilized photocatalyst devices for efficient and scalable OWS using one-step or two-step photoexcitation approaches are classified and summarized. For the case of the one-step photoexcitation approach, the whole OWS reaction can occur over a single photocatalyst, featuring a relatively simple structure, but it faces stringent restrictions on the band structure and active sites. In contrast, the Z-scheme route generally requires the HEP, the OEP and an electron mediator, all of which must be carefully designed and coupled for the effective interfacial charge transfer. Specifically, various types of solid-state electron mediators for immobilized Z-scheme OWS devices, such as metals, metal oxides, non-metals and biofilms, are concluded and illustrated. A concise overview of aforementioned representative Z-scheme OWS devices is provided in Table 3. Based on the current research progress, it is expected that further breakthroughs in the aspects, including but not limited to material screening, device construction, and system integration, will be made to advance the development of the immobilized photocatalyst systems toward practical applications.

| Photocatalytic system | Device area | Efficiency | Refs | ||

| Mediator | HEP | OEP | |||

| Au | Cr2O3/Ru-SrTiO3:La,Rh | RuOx-BiVO4:Mo | 7.5 cm2 | STH: 1.1% (10 kPa, 331 K) | [31] |

| RhCrOx-LaMg1/3Ta2/3O2N | BiVO4:Mo | 9 cm2 | STH: 0.001% | [62] | |

| Cr2O3/Rh-LTCA:Ga | BiVO4 | 8 cm2 | STH: 0.11% (5 kPa, 313 K) | [63] | |

| Pt/TiO2-CdS-ZCGSe | BiVO4:Mo | 8 cm2 | AQE: 1.5% (420 nm) | [65] | |

| Pt-Cu2O | MnOx-BiVO4:Mo | 9 cm2 | – | [68] | |

| ITO | Cr2O3/Ru-SrTiO3:La,Rh | RuOx-BiVO4:Mo | 6.25 cm2 | STH: 0.4% (91 kPa, 331 K) | [27] |

| In@InOx | Cr2O3/Ru-SrTiO3:Rh | CoOx-BiVO4:Mo | – | STH: 0.012% (5 kPa, 288 K) | [71] |

| C | Cr2O3/Ru-SrTiO3:La,Rh | BiVO4:Mo | 7.5 cm2 | STH: 1.2% (10 kPa, 331 K), STH: 1.0% (91 kPa, 331 K) | [28] |

| rGO | Cr2O3/Pt/IrO2-Sm2Ti2O5S2 | CoOx-BiVO4 | 6.25 cm2 | – | [32] |

| CNT | Cr2O3/Pt/IrO2-Sm2Ti2O5S2 | CoOx-BiVO4 | 6.25 cm2 | STH: 0.4% (10 kPa, 323 K) | [32] |

| Biofilm | Cr2O3/Ru-SrTiO3:Rh | CoOx-BiVO4:Mo | 9 cm2 | – | [29] |

| – | Ru-SrTiO3:Rh | BiVO4 | 3.2 cm2 | STH: 0.12% (5.33 kPa, 293 K) | [72] |

OWS: overall water splitting; HEP: H2 evolution photocatalyst; OEP: O2 evolution photocatalyst; STH: solar to hydrogen; AQE: apparent quantum efficiency; LTCA:Ga: Ga-doped La5Ti2Cu0.9Ag0.1S5O7; ZCGSe: (ZnSe)0.5(CuGa2.5Se4.25)0.5; ITO: Indium tin oxide; rGO: reduced graphene oxide; CNT: carbon nanotube; OWS: overall water splitting.

4. Conclusion and Outlook

This review systematically summarizes the main research progress of the immobilized photocatalyst devices for scalable OWS in terms of materials screening, device construction, and system integration, aiming to provide valuable guidance for translating efficient photocatalytic OWS systems from laboratory prototypes to engineering implementation. Despite rapid progress in this field, the STH conversion efficiency and the scalability level remain below expectations. To further address these challenges, the following issues are highlighted, and corresponding recommendations for future development are proposed.

(1) Material screening and innovative synthesis. To achieve a higher STH conversion efficiency, it is crucial to develop efficient photocatalysts with narrow bandgaps[74-78]. Furthermore, photocatalyst environmental safety must be fully considered, such as the heavy metal contamination caused by Cd2+ leaching from Cd-based photocatalysts. The traditional materials discovery relies on empirical iterative optimization or sequential testing, which is time-consuming, labor-intensive and constrained by human experience, making it difficult to identify globally optimal combinations. Artificial intelligence (AI), by learning structure-activity relationships, can precisely guide high-throughput screening and enable rapid evaluation of hundreds of combinations[79-83]. For instance, Li et al. employed machine learning to screen ternary organic heterojunction photocatalysts from a vast combinatorial space[82]. By training a model on electronic and structural descriptors, they identified effective candidates with high H2 evolution rates ever reported while reducing experimental screening by over 80%. Such integration of high-throughput screening with AI/machine learning can realize the transformation of future materials from design to targeted synthesis, offering an effective solution toward efficient and environmentally friendly photocatalysts.

(2) Design and construction of the innovative devices. Current immobilization techniques for powder photocatalysts often suffer from weak interfacial adhesion and low mass transfer efficiency[84-88]. To address these limitations, it is essential to modify the interfacial contact between the substrate and the particulate photocatalysts, such as roughening, chemical treatment, and plasma activation[89-92]. But for certain non-oxide photocatalysts, substrate roughening requires careful pre-treatment to preserve chemical stability, as excessive roughness can induce cracking in brittle lattices. In addition, alternative approaches, including binder-free assembly, low-temperature sintering, and self-assembly driven by charge or polarity differences between components, may also offer promising solutions. However, low-temperature sintering is limited to conditions below the decomposition point of materials to prevent degradation. These strategies will not only improve the mechanical stability of the photocatalyst layer, but also enhance the electronic coupling between photocatalysts and mediators, ultimately promoting immobilized photocatalyst devices[93].

(3) Understanding of the reaction mechanism. To provide a solid theoretical basis for the design of immobilized photocatalyst devices, it is crucial to deepen the understanding of the entire reaction process. Herein, advanced in situ time- and space-resolved analytical techniques, combined with theoretical calculations, are highly recommended for probing the real reaction process at both temporal and spatial dimensions. These techniques can help elucidate the details of the rate-determining step, and facilitate the design and construction of efficient photocatalyst systems[94-96].

(4) Development of application-oriented and scalable devices and systems. The scaling of OWS systems presents multifaceted challenges, such as safety risks, net energy output, and integration with hydrogen infrastructure. Overcoming these interconnected barriers requires the development of efficient, practical, and easily scalable novel technologies. Thin film preparation techniques, such as roll-to-roll processing[97,98], 3D printing[99-101], and interfacial polymerization[102,103], show substantial application potential. Such methods not only eliminate energy-intensive vacuum requirements and enable continuous operation, but also facilitate the design of integrated systems that are inherently safer and more resource-efficient. Furthermore, the development of efficient H2-O2 separation membranes (e.g., metal-organic frameworks[104]) and advanced H2 liquefaction technologies can mitigate the risk of explosive H2-O2 mixture while reducing the operational cost. By integrating these key technologies, it is expected that the net energy output can become positive.

To summarize, the immobilized photocatalyst devices for OWS have emerged as a promising approach for practical solar hydrogen production, exhibiting significant advantages over the powder suspension systems, such as scalability, facile recovery/replacement of photocatalysts, and the elimination of additional operations to disperse photocatalysts. Over the past decade, remarkable progress has been achieved in this field, particularly in materials screening, device construction, and system integration for scalable applications. Nonetheless, current technologies still require further development to meet the demands of large-scale implementation. It is our sincere hope that this review will attract more scientists from diverse disciplines to advance this field and accelerate its transition to industrial-scale applications.

Authors contribution

Chen S, Ma B: Supervision, writing-review & editing.

Shao Y, Wang S: Conceptualization, writing-original draft.

All of the authors discussed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22272082, 22572089), the Funds for International Cooperation and Exchange of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (W2421036), Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Natural Science Foundation Cooperation Project (25JJJJC0010), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, Nankai University (63213098).

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

References

-

1. Chu Y, Zhao F, Meng F, Zhang W, Zhao J, Zhong X. Donor-acceptor type conjugated porous polymers based on benzotrithiophen and triazine derivatives: Effect of linkage unit on photocatalytic water splitting. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2024;64:109-119.[DOI]

-

2. Hasan I, El Marghany A, Abduh NAY, Alharthi FA. Efficient Zinc vanadate homojunction with cadmium nanostructures for photocatalytic water splitting and hydrogen evolution. Nanomaterials. 2024;14(6):492.[DOI]

-

3. Nishioka S, Osterloh FE, Wang X, Mallouk TE, Maeda K. Photocatalytic water splitting. Nat Rev Methods Primers. 2023;3(1):43.[DOI]

-

4. Avcıoğlu C, Avcıoğlu S, Bekheet MF, Gurlo A. Solar hydrogen generation using niobium-based photocatalysts: Design strategies, progress, and challenges. Mater Today Energy. 2022;24:100936.[DOI]

-

5. Zhang Y, Wu X, Wang Z-H, Peng Y, Liu Y, Yang S, et al. Crystal facet engineering on SrTiO3 enhances photocatalytic overall water splitting. J Am Chem Soc. 2024;146(10):6618-6627.[DOI]

-

6. Segev G, Kibsgaard J, Hahn C, Xu ZJ, Cheng WH, Deutsch TG, et al. The 2022 solar fuels roadmap. J Phys D: Appl Phys. 2022;55(32):323003.[DOI]

-

7. Xu YF, Tountas AA, Song R, Ye J, Wei JH, Ji S, et al. Equilibrium photo-thermodynamics enables a sustainable methanol synthesis. Joule. 2023;7(4):738-752.[DOI]

-

8. Hisatomi T, Domen K. Overall water splitting: What’s next? Next Energy. 2023;1(1):100006.[DOI]

-

9. Wang K, Li Z, Liu T, Gao W, Yang T, Liu K, et al. Boosting long-chain linear α-olefins synthesis from CO2 hydrogenation over K-femn catalyst via stabilizing active sites. ACS Catal. 2024;14(23):17469-17479.[DOI]

-

10. Di J, Wu Y, Xiong J, Shou H, Long R, Chen H, et al. Asymmetric associate configuration of Nb single atoms coupled Bi–O vacancy pairs boosting CO2 photoreduction. ACS Catal. 2024;14(23):17818-17824.[DOI]

-

11. Jiang XL, Zhuang J, Deng G, Lu JB, Zhao C, Jiang N, et al. Molecular uranium dioxide-mediated CO2 photoreduction. J Am Chem Soc. 2025;147(6):4726-4730.[DOI]

-

12. Zhang Y, Wei T, Ding D, Wang K, Di J, Tseng J, et al. Aggregation-induced equidistant dual Pt atom pairs for effective CO2 photoreduction to C2H4. ACS Catal. 2025;15(7):5614-5622.[DOI]

-

13. Li H, Tu W, Zhou Y, Zou Z. Z-scheme photocatalytic systems for promoting photocatalytic performance: Recent progress and future challenges. Adv Sci. 2016;3(11):1500389.[DOI]

-

14. Chen S, Takata T, Domen K. Particulate photocatalysts for overall water splitting. Nat Rev Mater. 2017;2(10):17050.[DOI]

-

15. Nandy S, Savant SA, Haussener S. Prospects and challenges in designing photocatalytic particle suspension reactors for solar fuel processing. Chem Sci. 2021;12(29):9866-9884.[DOI]

-

16. Wang Y, Suzuki H, Xie J, Tomita O, Martin DJ, Higashi M, et al. Mimicking natural photosynthesis: Solar to renewable H2 fuel synthesis by Z-scheme water splitting systems. Chem Rev. 2018;118(10):5201-5241.[DOI]

-

17. Kudo A. Z-scheme photocatalyst systems for water splitting under visible light irradiation. MRS Bulletin. 2011;36(1):32-38.[DOI]

-

18. Maeda K. Z-scheme water splitting using two different semiconductor photocatalysts. ACS Catal. 2013;3(7):1486-1503.[DOI]

-

19. Fujito H, Kunioku H, Kato D, Suzuki H, Higashi M, Kageyama H, et al. Layered perovskite oxychloride Bi4NbO8Cl: A stable visible light responsive photocatalyst for water splitting. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138(7):2082-2085.[DOI]

-

20. Pan Z, Zhang G, Wang X. Polymeric carbon nitride/reduced graphene oxide/Fe2O3: All-solid-state Z-scheme system for photocatalytic overall water splitting. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2019;58(21):7102-7106.[DOI]

-

21. Wang Z, Li C, Domen K. Recent developments in heterogeneous photocatalysts for solar-driven overall water splitting. Chem Soc Rev. 2019;48(7):2109-2125.[DOI]

-

22. Wang K, Luo Y, Gu C, Zhi T, Wang L, Yan D. Recent developments in immobilized photocatalyst for hydrogen production. ChemCatChem. 2024;16(22):e202400930.[DOI]

-

23. Wei Y, Zhang Z, Wang W, Song Z, Cai M, Sun S. Photocatalytic Z-scheme overall water splitting: Insight into different optimization strategies for powder suspension and particulate sheet systems. ChemPhysChem. 2023;24(16):e202300216.[DOI]

-

24. Nandy S, Hisatomi T, Takata T, Setoyama T, Domen K. Recent advances in photocatalyst sheet development and challenges for cost-effective solar hydrogen production. J Mater Chem A. 2023;11(38):20470-20479.

-

25. Goto Y, Hisatomi T, Wang Q, Higashi T, Ishikiriyama K, Maeda T, et al. A particulate photocatalyst water-splitting panel for large-scale solar hydrogen generation. Joule. 2018;2(3):509-520.[DOI]

-

26. Wang Q, Li Y, Hisatomi T, Nakabayashi M, Shibata N, Kubota J, et al. Z-scheme water splitting using particulate semiconductors immobilized onto metal layers for efficient electron relay. J Catal. 2015;328:308-315.[DOI]

-

27. Wang Q, Okunaka S, Tokudome H, Hisatomi T, Nakabayashi M, Shibata N, et al. Printable photocatalyst sheets incorporating a transparent conductive mediator for Z-scheme water splitting. Joule. 2018;2(12):2667-2680.[DOI]

-

28. Wang Q, Hisatomi T, Suzuki Y, Pan Z, Seo J, Katayama M, et al. Particulate photocatalyst sheets based on carbon conductor layer for efficient Z-scheme pure-water splitting at ambient pressure. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139(4):1675-1683.[DOI]

-

29. Wang X, Zhang B, Zhang J, Jiang X, Liu K, Wang H, et al. Conformal and conductive biofilm-bridged artificial Z-scheme system for visible light-driven overall water splitting. Sci Adv. 2024;10(24):eadn6211.[DOI]

-

30. Nishiyama H, Yamada T, Nakabayashi M, Maehara Y, Yamaguchi M, Kuromiya Y, et al. Photocatalytic solar hydrogen production from water on a 100-m2 scale. Nature. 2021;598(7880):304-307.[DOI]

-

31. Wang Q, Hisatomi T, Jia Q, Tokudome H, Zhong M, Wang C, et al. Scalable water splitting on particulate photocatalyst sheets with a solar-to-hydrogen energy conversion efficiency exceeding 1%. Nature Mater. 2016;15(6):611-615.[DOI]

-

32. Gu C, Miseki Y, Nishiyama H, Takata T, Yoshimura J, Ma Y, et al. Carbon-conductor-based photocatalyst sheets fabricated by a facile filtration process for efficient, stable, and scalable water splitting. Chem Catal. 2025;5(3):101233.[DOI]

-

33. Wang Q, Domen K. Particulate photocatalysts for light-driven water splitting: Mechanisms, challenges, and design strategies. Chem Rev. 2020;120(2):919-985.[DOI]

-

34. Barber J. Photosynthetic energy conversion: Natural and artificial. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38(1):185-196.[DOI]

-

35. Bard AJ. Photoelectrochemistry and heterogeneous photo-catalysis at semiconductors. J Photochem. 1979;10(1):59-75.[DOI]

-

36. Chen S, Qi Y, Li C, Domen K, Zhang F. Surface strategies for particulate photocatalysts toward artificial photosynthesis. Joule. 2018;2(11):2260-2288.[DOI]

-

37. Zhao W, Maeda K, Zhang F, Hisatomi T, Domen K. Effect of post-treatments on the photocatalytic activity of Sm2Ti2S2O5 for the hydrogen evolution reaction. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2014;16(24):12051-12056.[DOI]

-

38. Fu H, Zhang Q, Liu Y, Zheng Z, Cheng H, Huang B, et al. Photocatalytic overall water splitting with a solar-to-hydrogen conversion efficiency exceeding 2 % through halide perovskite. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2024;63(49):e202411016.[DOI]

-

39. Kato H, Hori M, Konta R, Shimodaira Y, Kudo A. Construction of Z-scheme type heterogeneous photocatalysis systems for water splitting into H2 and O2 under visible light irradiation. Chem Lett. 2004;33(10):1348-1349.[DOI]

-

40. Sasaki Y, Kato H, Kudo A. [Co(bpy)3]3+/2+ and [Co(phen)3]3+/2+ electron mediators for overall water splitting under sunlight irradiation using Z-scheme photocatalyst system. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135(14):5441-5449.[DOI]

-

41. Qi Y, Zhang J, Kong Y, Zhao Y, Chen S, Li D, et al. Unraveling of cocatalysts photodeposited selectively on facets of BiVO4 to boost solar water splitting. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):484.[DOI]

-

42. Lee WH, Lee CW, Cha GD, Lee B-H, Jeong JH, Park H, et al. Floatable photocatalytic hydrogel nanocomposites for large-scale solar hydrogen production. Nat Nanotechnol. 2023;18(7):754-762.[DOI]

-

43. Tada H, Mitsui T, Kiyonaga T, Akita T, Tanaka K. All-solid-state z-scheme in CdS–Au–TiO2 three-component nanojunction system. Nature Mater. 2006;5(10):782-786.[DOI]

-

44. Hisatomi T, Takanabe K, Domen K. Photocatalytic water-splitting reaction from catalytic and kinetic perspectives. Catal Lett. 2015;145(1):95-108.[DOI]

-

45. Hisatomi T, Kubota J, Domen K. Recent advances in semiconductors for photocatalytic and photoelectrochemical water splitting. Chem Soc Rev. 2014;43(22):7520-7535.[DOI]

-

46. Qi Y, Zhang F. Recent advances in redox-based Z-scheme overall water splitting under visible light irradiation. J Phys Chem Lett. 2024;15(11):2976-2987.[DOI]

-

47. Ma Y, Lin L, Takata T, Hisatomi T, Domen K. A perspective on two pathways of photocatalytic water splitting and their practical application systems. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2023;25(9):6586-6601.[DOI]

-

48. Hisatomi T, Domen K. Progress in the demonstration and understanding of water splitting using particulate photocatalysts. Curr Opin Electrochem. 2017;2(1):148-154.[DOI]

-

49. Kato H, Sasaki Y, Iwase A, Kudo A. Role of iron ion electron mediator on photocatalytic overall water splitting under visible light irradiation using Z-scheme systems. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 2007;80(12):2457-2464.[DOI]

-

50. Higashi M, Abe R, Teramura K, Takata T, Ohtani B, Domen K. Two step water splitting into H2 and O2 under visible light by ATaO2N (A=Ca, Sr, Ba) and WO3 with IO3-/I-shuttle redox mediator. Chem Phys Lett. 2008;452(1):120-123.[DOI]

-

51. Maeda K, Higashi M, Lu D, Abe R, Domen K. Efficient nonsacrificial water splitting through two-step photoexcitation by visible light using a modified oxynitride as a hydrogen evolution photocatalyst. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(16):5858-5868.[DOI]

-

52. Hisatomi T, Yamada T, Nishiyama H, Takata T, Domen K. Materials and systems for large-scale photocatalytic water splitting. Nat Rev Mater. 2025;10(10):769-782.[DOI]

-

53. Pham TA, Ping Y, Galli G. Modelling heterogeneous interfaces for solar water splitting. Nature Mater. 2017;16(4):401-408.[DOI]

-

54. Tee SY, Win KY, Teo WS, Koh L-D, Liu S, Teng CP, et al. Recent progress in energy-driven water splitting. Adv Sci. 2017;4(5):1600337.[DOI]

-

55. Fu CF, Wu X, Yang J. Material design for photocatalytic water splitting from a theoretical perspective. Adv Mater. 2018;30(48):1802106.[DOI]

-

56. Lin L, Ma Y, Vequizo JJM, Nakabayashi M, Gu C, Tao X, et al. Efficient and stable visible-light-driven Z-scheme overall water splitting using an oxysulfide H2 evolution photocatalyst. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):397.[DOI]

-

57. Xiong A, Ma G, Maeda K, Takata T, Hisatomi T, Setoyama T, et al. Fabrication of photocatalyst panels and the factors determining their activity for water splitting. Catal Sci Technol. 2014;4(2):325-328.[DOI]

-

58. Zhou P, Navid IA, Ma Y, Xiao Y, Wang P, Ye Z, et al. Solar-to-hydrogen efficiency of more than 9% in photocatalytic water splitting. Nature. 2023;613(7942):66-70.[DOI]

-

59. Moses PG, Van de Walle CG. Band bowing and band alignment in InGaN alloys. Appl Phys Lett. 2010;96(2):021908.[DOI]

-

60. Wang Y, Wu Y, Sun K, Mi Z. A quadruple-band metal–nitride nanowire artificial photosynthesis system for high efficiency photocatalytic overall solar water splitting. Mater Horiz. 2019;6(7):1454-1462.[DOI]

-

61. Wang Q, Hisatomi T, Katayama M, Takata T, Minegishi T, Kudo A, et al. Particulate photocatalyst sheets for Z-scheme water splitting: Advantages over powder suspension and photoelectrochemical systems and future challenges. Faraday Discuss. 2017;197(0):491-504.[DOI]

-

62. Pan Z, Hisatomi T, Wang Q, Chen S, Nakabayashi M, Shibata N, et al. Photocatalyst sheets composed of particulate LaMg1/3Ta2/3O2N and Mo-doped BiVO4 for Z-scheme water splitting under visible light. ACS Catal. 2016;6(10):7188-7196.[DOI]

-

63. Sun S, Hisatomi T, Wang Q, Chen S, Ma G, Liu J, et al. Efficient redox-mediator-free Z-scheme water splitting employing oxysulfide photocatalysts under visible light. ACS Catal. 2018;8(3):1690-1696.[DOI]

-

64. Chen S, Ma G, Wang Q, Sun S, Hisatomi T, Higashi T, et al. Metal selenide photocatalysts for visible-light-driven Z-scheme pure water splitting. J Mater Chem A. 2019;7(13):7415-7422.[DOI]

-

65. Chen S, Vequizo JJM, Pan Z, Hisatomi T, Nakabayashi M, Lin L, et al. Surface modifications of (ZnSe)0.5(CuGa2.5Se4.25)0.5 to promote photocatalytic Z-scheme overall water splitting. J Am Chem Soc. 2021;143(28):10633-10641.[DOI]

-

66. Hisatomi T, Okamura S, Liu J, Shinohara Y, Ueda K, Higashi T, et al. La5Ti2Cu1-xAgxS5O7 photocathodes operating at positive potentials during photoelectrochemical hydrogen evolution under irradiation of up to 710 nm. Energy Environ Sci. 2015;8(11):3354-3362.[DOI]

-

67. Liu K, Zhang B, Zhang J, Lin W, Wang J, Xu Y, et al. Synthesis of narrow-band-gap GaN: ZnO solid solution for photocatalytic overall water splitting. ACS Catal. 2022;12(23):14637-14646.[DOI]

-

68. Zhu H, Zhen C, Chen X, Feng S, Li B, Du Y, et al. Patterning alternate TiO2 and Cu2O strips on a conductive substrate as film photocatalyst for Z-scheme photocatalytic water splitting. Sci Bull. 2022;67(23):2420-2427.[DOI]

-

69. Zhen C, Zhu H, Chen R, Zheng Z, Fan F, Li B, et al. An artificial leaf with patterned photocatalysts for sunlight-driven water splitting. J Am Chem Soc. 2024;146(41):28482-28490.[DOI]

-

70. Wang Q, Kalathil S, Pornrungroj C, Sahm CD, Reisner E. Bacteria–photocatalyst sheet for sustainable carbon dioxide utilization. Nat Catal. 2022;5(7):633-641.[DOI]

-

71. Zhang B, Liu K, Xiang Y, Wang J, Lin W, Guo M, et al. Facet-oriented assembly of Mo: BiVO4 and Rh: SrTiO3 particles: Integration of p–n conjugated photo-electrochemical system in a particle applied to photocatalytic overall water splitting. ACS Catal. 2022;12(4):2415-2425.[DOI]

-

72. Sasaki Y, Nemoto H, Saito K, Kudo A. Solar water splitting using powdered photocatalysts driven by Z-schematic interparticle electron transfer without an electron mediator. J Phys Chem C. 2009;113(40):17536-17542.[DOI]

-

73. Jia Q, Iwase A, Kudo A. BiVO4–Ru/SrTiO3: Rh composite Z-scheme photocatalyst for solar water splitting. Chem Sci. 2014;5(4):1513-1519.[DOI]

-

74. Yang J, Wang D, Han H, Li C. Roles of cocatalysts in photocatalysis and photoelectrocatalysis. Acc Chem Res. 2013;46(8):1900-1909.[DOI]

-

75. Xia X, Song M, Wang H, Zhang X, Sui N, Zhang Q, et al. Latest progress in constructing solid-state Z scheme photocatalysts for water splitting. Nanoscale. 2019;11(23):11071-11082.[DOI]

-

76. Wang L, Bie C, Yu J. Challenges of Z-scheme photocatalytic mechanisms. Trends Chem. 2022;4(11):973-983.[DOI]

-

77. Low J, Jiang C, Cheng B, Wageh S, Al-Ghamdi AA, Yu J. A review of direct Z-scheme photocatalysts. Small Methods. 2017;1(5):1700080.[DOI]

-

78. Shaner MR, Atwater HA, Lewis NS, McFarland EW. A comparative technoeconomic analysis of renewable hydrogen production using solar energy. Energy Environ Sci. 2016;9(7):2354-2371.[DOI]

-

79. Zhang W, Yu M, Liu T, Cong M, Liu X, Yang H, et al. Accelerated discovery of molecular nanojunction photocatalysts for hydrogen evolution by using automated screening and flow synthesis. Nat Synth. 2024;3(5):595-605.[DOI]

-

80. Li X, Che Y, Chen L, Liu T, Wang K, Liu L, et al. Sequential closed-loop bayesian optimization as a guide for organic molecular metallophotocatalyst formulation discovery. Nat Chem. 2024;16(8):1286-1294.[DOI]

-

81. Yang H, Li C, Liu T, Fellowes T, Chong SY, Catalano L, et al. Packing-induced selectivity switching in molecular nanoparticle photocatalysts for hydrogen and hydrogen peroxide production. Nat Nanotechnol. 2023;18(3):307-315.[DOI]

-

82. Yang H, Che Y, Cooper AI, Chen L, Li X. Machine learning accelerated exploration of ternary organic heterojunction photocatalysts for sacrificial hydrogen evolution. J Am Chem Soc. 2023;145(49):27038-27044.[DOI]

-

83. Liu L, Gao MY, Yang H, Wang X, Li X, Cooper AI. Linear conjugated polymers for solar-driven hydrogen peroxide production: The importance of catalyst stability. J Am Chem Soc. 2021;143(46):19287-19293.[DOI]

-

84. Kamijyo K, Takashima T, Yoda M, Osaki J, Irie H. Facile synthesis of a red light-inducible overall water-splitting photocatalyst using gold as a solid-state electron mediator. Chem Commun. 2018;54(57):7999-8002.[DOI]

-

85. Pan C, Takata T, Nakabayashi M, Matsumoto T, Shibata N, Ikuhara Y, et al. A complex perovskite‐type oxynitride: The first photocatalyst for water splitting operable at up to 600 nm. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54(10):2955-2959.[DOI]

-

86. Wang Z, Inoue Y, Hisatomi T, Ishikawa R, Wang Q, Takata T, et al. Overall water splitting by Ta3N5 nanorod single crystals grown on the edges of KTaO3 particles. Nat Catal. 2018;1(10):756-763.[DOI]

-

87. Wang X, Liu G, Wang L, Chen Z-G, Lu GQ, Cheng H-M. ZnO–CdS@Cd heterostructure for effective photocatalytic hydrogen generation. Adv Energy Mater. 2012;2(1):42-46.[DOI]

-

88. Kahn A. Fermi level, work function and vacuum level. Mater Horiz. 2016;3(1):7-10.[DOI]

-

89. Zhang F, Yamakata A, Maeda K, Moriya Y, Takata T, Kubota J, et al. Cobalt-modified porous single-crystalline LaTiO2N for highly efficient water oxidation under visible light. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134(20):8348-8351.[DOI]

-

90. Wagner LI, Sirotti E, Brune O, Grötzner G, Eichhorn J, Santra S, et al. Defect engineering of Ta3N5 photoanodes: enhancing charge transport and photoconversion efficiencies via Ti doping. Adv Funct Mater. 2024;34(4):2306539.[DOI]

-

91. An H, Wang Y, Xiao X, Liu J, Ma Z, Gao T, et al. Photocatalytic seawater splitting by 2D heterostructure of ZnIn2S4/WO3 decorated with plasmonic Au for hydrogen evolution under visible light. J Energy Chem. 2024;93:55-63.[DOI]

-

92. Li Z, Mao Y, Huang Y, Wei D, Chen M, Huang Y, et al. Theoretical and experimental studies of highly efficient all-solid Z-scheme TiO2–TiC/gC3 N4 for photocatalytic CO2 reduction via dry reforming of methane. Catal Sci Technol. 2022;12(9):2804-2818.[DOI]

-

93. Gu C, Hisatomi T, Takata T, Domen K. Z-scheme water splitting systems based on solid-state electron conductors. Adv Funct Mater. 2025;19:2506171.[DOI]

-

94. Askarova G, Xiao C, Barman K, Wang X, Zhang L, Osterloh FE, et al. Photo-scanning electrochemical microscopy observation of overall water splitting at a single aluminum-doped strontium titanium oxide microcrystal. J Am Chem Soc. 2023;145(11):6526-6534.[DOI]

-

95. Sambur JB, Chen T-Y, Choudhary E, Chen G, Nissen EJ, Thomas EM, et al. Sub-particle reaction and photocurrent mapping to optimize catalyst-modified photoanodes. Nature. 2016;530(7588):77-80.[DOI]

-

96. Xu X, Meng L, Zhang J, Yang S, Sun C, Li H, et al. Full-spectrum responsive naphthalimide/perylene diimide with a giant internal electric field for photocatalytic overall water splitting. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2024;63(5):e202308597.[DOI]

-

97. Singh B, Gautam S, Behera GC, Aggarwal V, Kumar R, Kumar M, et al. Bi2Se3/SnSe heterojunction on flexible Ti foil for enhanced photoelectrochemical water splitting. Mater Lett. 2024;355:135503.[DOI]

-

98. Singh B, Gautam S, Behera GC, Kumar R, Aggarwal V, Tawale JS, et al. MoS2 thin film decorated TiO2 nanotube arrays on flexible Ti foil for solar water splitting application. Nano Express. 2024;5(1):015006.[DOI]

-

99. Chen P, Wu K, Peng X, Ma Y, Yang X, Duan X, et al. Design of a Z-scheme printable artificial leaf device based on CdS@TiO2/Pt/ITO/WO3@Co3O4 for water splitting. Appl Phys A. 2021;128(1):80.[DOI]

-

100. Elkoro A, Soler L, Llorca J, Casanova I. 3D printed microstructured Au/TiO2 catalyst for hydrogen photoproduction. Appl Mater Today. 2019;16:265-272.[DOI]

-

101. Li N, Kong W, Gao J, Wu Y, Kong Y, Chen L, et al. 3D printed textured substrate with ZnIn2S4-Pt-Co thermoset coating for photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2024;71:1351-1362.[DOI]

-

102. Lang X, Gopalan S, Fu W, Ramakrishna S. Photocatalytic water splitting utilizing electrospun semiconductors for solar hydrogen generation: Fabrication, modification and performance. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 2021;94(1):8-20.[DOI]

-

103. Zhang F, Fan J, Wang S. Interfacial polymerization: From chemistry to functional materials. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2020;59(49):21840-21856.[DOI]

-

104. Cheng SQ, Liu Y, Sun Y. Macrocycle-based metal-organic and covalent organic framework membranes. Coord Chem Rev. 2025;534:216559.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite