Moyuan Cao, School of Materials Science and Engineering, Tianjin Key Laboratory of Metal and Molecular Materials Chemistry, Frontiers Science Center for New Organic Matter, Academy for Advanced Interdisciplinary Studies, Nankai University, Tianjin 300350, China. E-mail: mycao@nankai.edu.cn

Abstract

The aggregation, distribution, spreading, elongation and shrinking, as well as other behaviors of liquids, along with mass transfer and thermal exchange, are ubiquitous in both natural creatures and human daily life. These phenomena greatly inspire the advancement of liquid manipulating interfaces in theoretical models, production processes, and performance optimization. After decades of development, regulating liquid movements through surface chemistry, micro/nano structures, and geometrical gradients is becoming increasingly prevalent but still faces challenges. This review discusses the design principles of liquid manipulating interfaces, bionic prototypes and its models behind, and introduces their specific role within these works. We summarize state-of-the-art works from different motion dimensions, as well as the most widely mentioned applications. We believe this can inspire the transfer of bioinspired structures into functional devices through continued innovative breakthroughs and multidisciplinary collaboration.

Keywords

1. Introduction

Regulating liquid movements is pivotal for both natural creatures[1-3] and human society[4-8], motivating extensive research interests and efforts over the past decades[9-13]. The utilization of liquid manipulating interfaces, especially for the spontaneous spreading of bulk droplets, significantly promotes system efficiency across diverse applications, including liquid uptake/digestion processes of natural organisms, as well as engineering innovations in wearable devices[14-16], chip cooling[17,18], smart dressings[19-21], porous materials[22], water harvesting[23-25] air purification[26], etc. Driven by the rapidly progressing bionics and modern manufacturing technologies, fundamental mechanisms about the evolution of liquid manipulating interfaces are progressively elucidated, for example, droplet aggregation on spider silk[27], directional self-transport on cactus thorns[28], water repellency on lotus leaves[29], and unidirectional liquid self-transport on pitcher plants[30]. Scientific research and engineered solutions thus greatly benefit from these natural systems[31-37].

Exploiting current achievements in human production and daily life relies deeply on the reproduction and surpassing of bioinspired functionalities, in other words, the rapid renovation of emerging devices. From this perspective, researchers encounter three challenges: (i) What’s the key point of the liquid spreading? A systematic synthesis of current theories and models can help to understand diverse natural phenomena where liquids move spontaneously. (ii) How can practical devices be produced efficiently based on these findings? Thorough assessments and practicable guidelines, derived from cross-disciplinary advancements, are needed to bridge the gap between bioinspired structures to scalable engineering devices. (iii) Under what conditions do bioinspired liquid manipulating interfaces outperform conventional equipment? Targeted investigations into performance bottlenecks are critical to identify transformative application scenarios where bioinspired structures demonstrate clear advantages. With joint efforts and collaborative innovations, can laboratory breakthroughs be transited to real-world implementations, unlocking the full potential of bioinspired liquid manipulating interfaces.

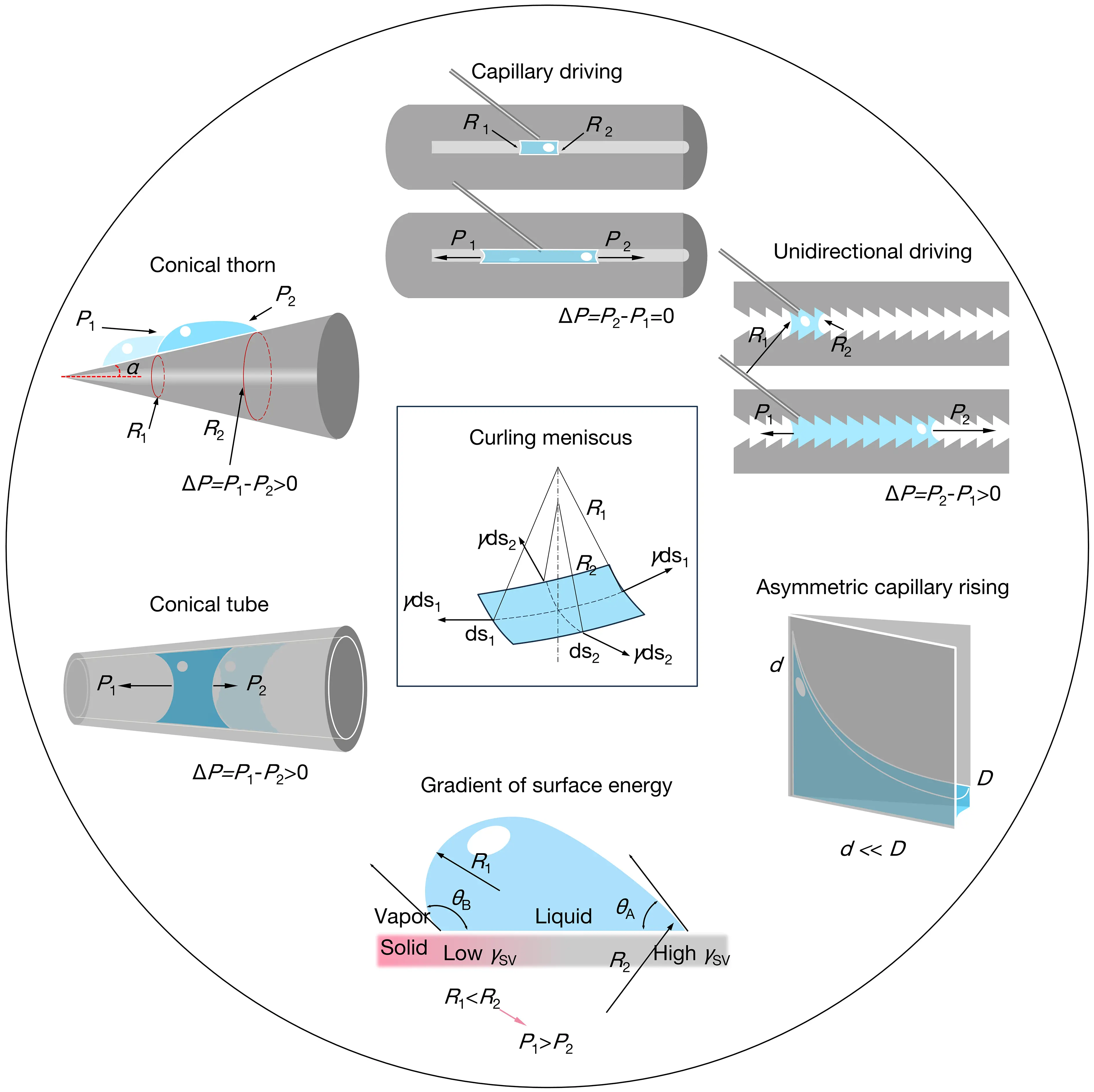

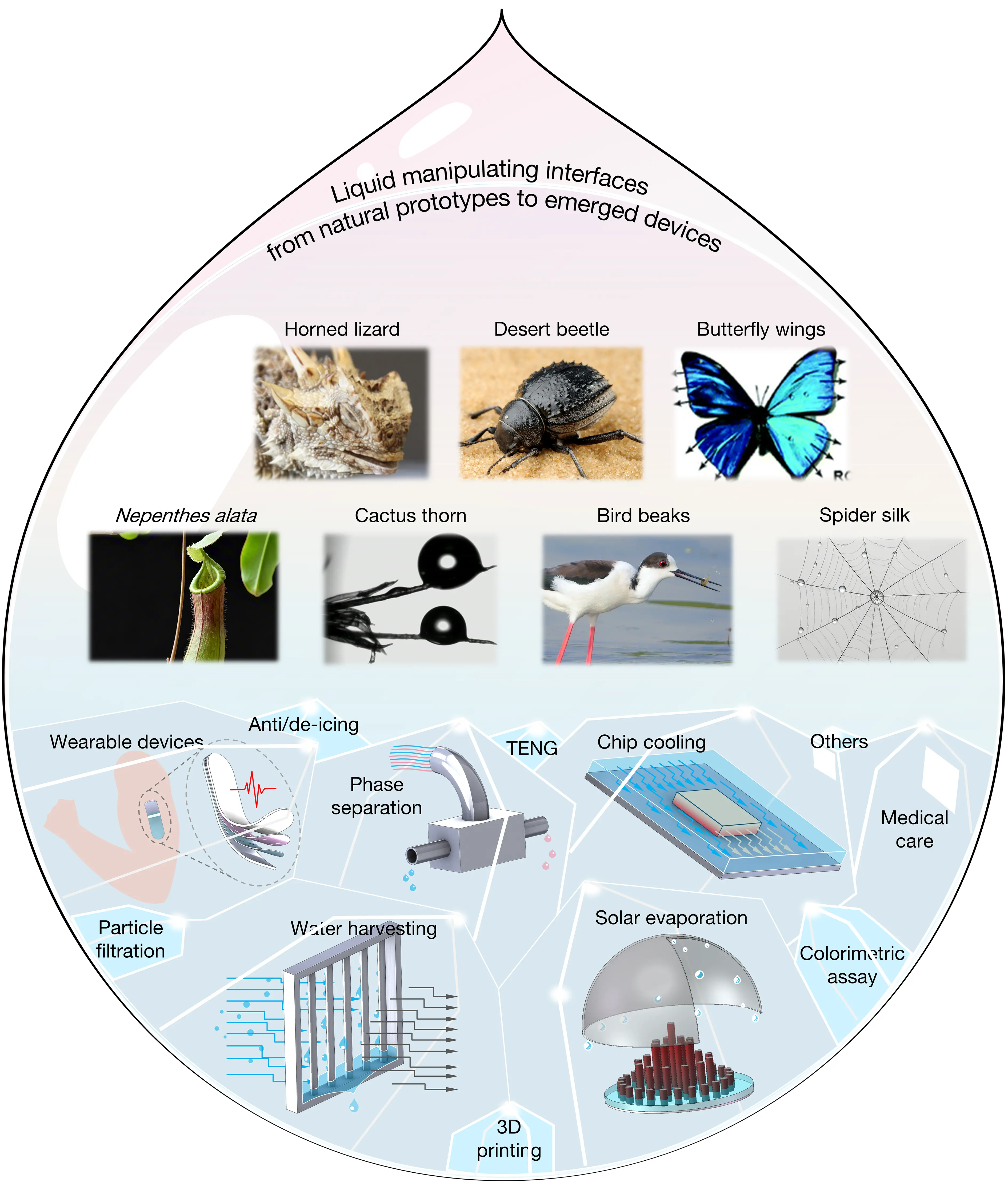

In this paper, we first introduce the most studied liquid behaviors observed in both biological systems and engineered processes (Figure 1). These evolved biomimetic features have inspired researchers to address challenges in science and technology. We then summarize theoretical models of liquid manipulating interfaces, especially the curling meniscus between solid-liquid or liquid-gas contacting areas, providing a deep understanding of the spontaneous spreading of liquids (Figure 2). Subsequently, the potential application scenarios are discussed and highlighted comprehensively (Figure 3, Figure 4). We divide the state-of-the-art liquid manipulating interfaces into three main motion modalities, including i) one-dimensional (1D) fiber-guided transport, ii) two-dimensional (2D) on-surface delivery, and iii) three-dimensional (3D) stereoscopic spreading. Besides, ten key features of the mentioned application scenarios are summarized to guide future research and engineering. Finally, we outline promising directions and personal outlooks on future advancements in functional devices incorporating intelligent liquid manipulating interfaces. These insights aim to handle current challenges of technological bottlenecks while inspiring more remarkable practical progress across multiple disciplines.

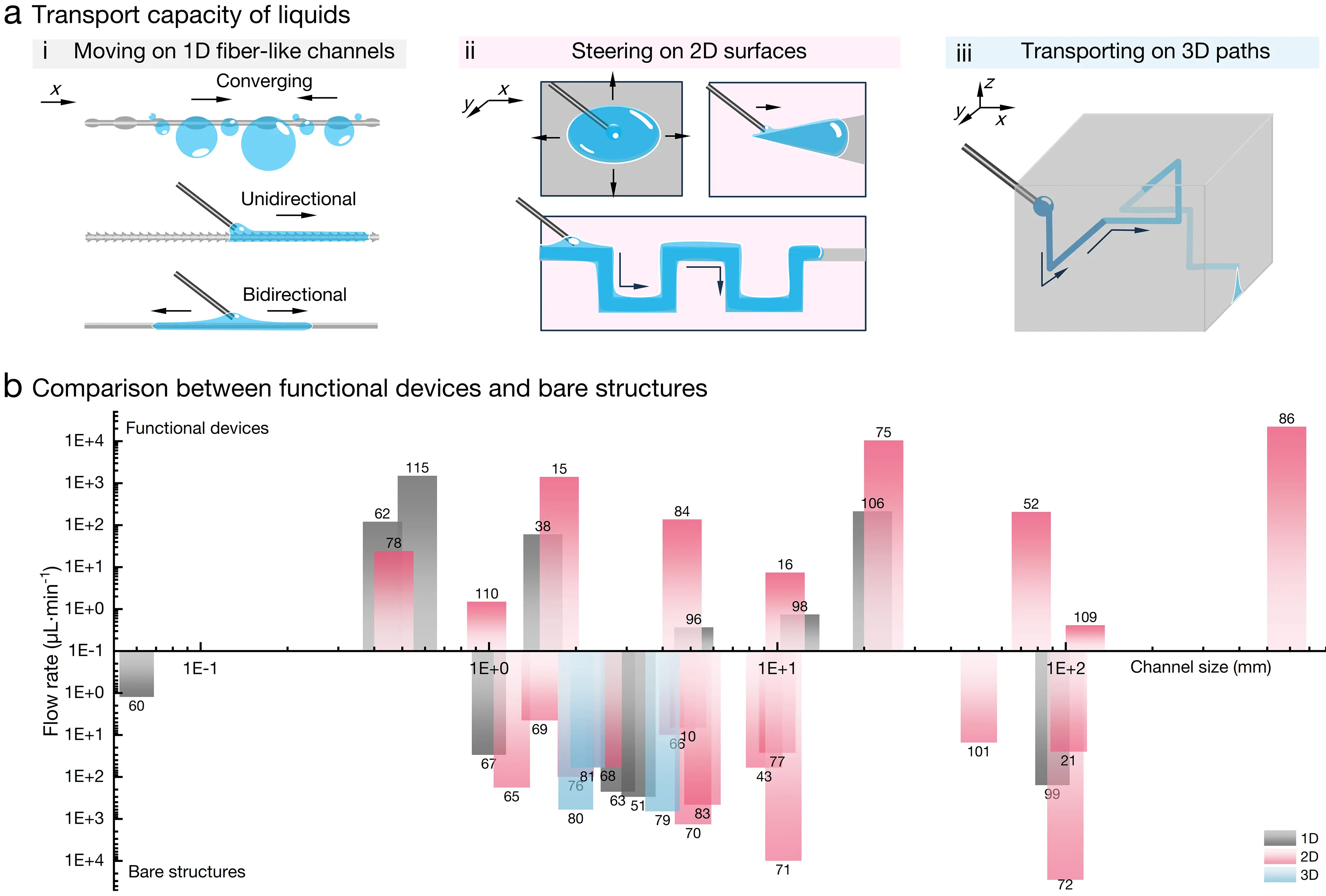

Figure 3. Categories of liquid manipulating interfaces among the latest works. (a) 1D fiber like channels, 2D substrates, and 3D architectures; (b) Statistics of recent advancements of bionic structures and functional devices. Numbers represent the orders of references; 1D: one-dimensional; 2D: two-dimensional; 3D: three-dimensional.

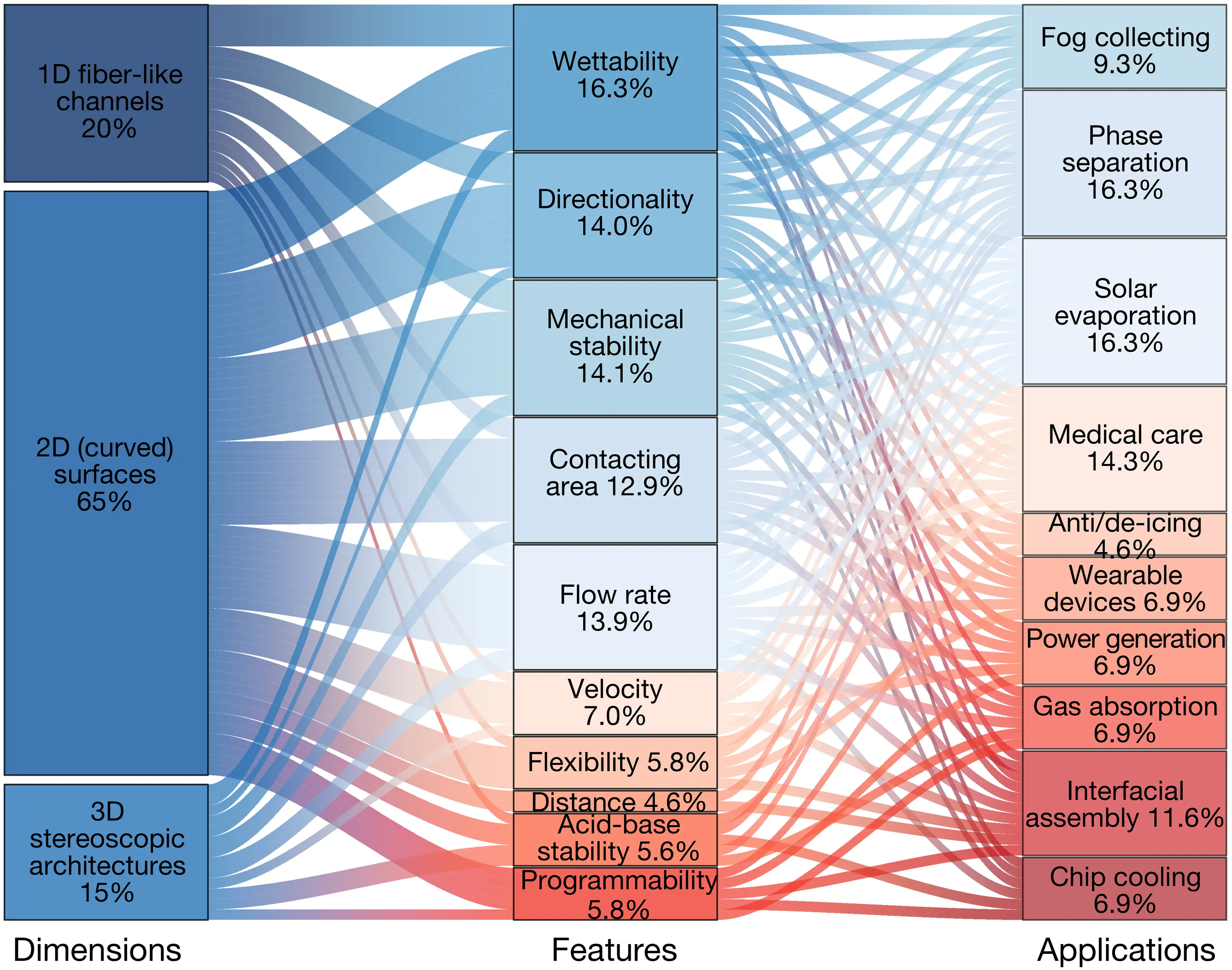

Figure 4. Key features of functional devices in diverse dimensions. Statistics represent the proportion of corresponding character within the summarized references. 1D: one-dimensional; 2D: two-dimensional; 3D: three-dimensional.

2. Liquid Manipulating Interfaces Evolved by Nature

2.1 Bionic prototypes

Over hundreds of thousands of years, natural creatures gradually evolved efficient liquid self-transport capability to survive in harsh environments (Figure 1). Meanwhile, bionic science has witnessed quick progresses in the past few decades, attributed to the development of biomimetic fundamentals and cutting-edge manufacturing methods. This progress, in turn, creates a pressing need for deeper understanding of such characteristics and behaviors to tackle the ongoing industrial challenges. Take, for instance, the horned lizard whose open-capillary skin can drive water against gravity to its mouth[3], which inspired advanced chip cooling systems with high thermal flow rate and phase-change heat conduction. The back of the desert beetle is capable of capturing water from foggy airflow[38], playing a significant role in its survival in rigid areas, and, in turn, facilitating abundant atmospheric water harvesting devices with patterned wettability[11].

Besides, cactus thorns[28] improve its fog collecting efficiency and significantly promote the design intelligence of artificial materials like used for oil-water separation. Similarly, spider silk[27] enables efficient droplet aggregation and collecting through inherent spindle knots and joint structures, also enlightening the latest fog collecting devices. The water repellency property of butterfly wings[39], induced by inclined scale arrays, enables them to keep dry in rainy days, also inspiring on-surface droplet directional bouncing. The unidirectional capillary rise within the peristome of Nepenthes alata[30,40] allows for unidirectional liquid self-transport and super lubrication, enhancing preying efficiency and advanced open-capillary systems. Similarly, some bird beaks[1] evolved a unique ratchet effect allowing antigravity movement of droplets during feeding processes. These spectacular behaviors of creatures pave the way for solving challenges in fields like wearable devices, phase separation, fluid “diodes”, 3D printing, and even intelligent medical care.

2.2 Fundamentals and theories

The precise and spontaneous spreading of liquids mainly hinges on the regulation of curling meniscus, induced by asymmetric geometry, surface micro/nano structures, and gradients of surface energy. Among these studies, three fundamental mechanisms, Laplace pressure difference, capillary effect, and wettability gradient, have been extensively explored and validated, but all are derived from surface tension, the interfacial tension between liquid and gas[41].

Laplace pressure difference arises from the asymmetric curvature of the liquid meniscus, which is induced by a geometrical gradient[42,43]. For example, the cactus thorn, featured by a sharp tip and a broader base, presents typical geometric gradients and can allow directional self-transport of droplets[44]. Seen from Figure 2, with the existence of surface tension, a liquid meniscus, with asymmetrically curled interfaces can cause a considerable Laplace pressure difference, ΔP, which can be deduced by:

where R1 and R2 represent local radii, α is the half apex angle, γ is the liquid surface tension, and r is the integration variable.

Capillary rise, widely found when liquids encounter tiny surface structures, like open or close microgrooves and microtubes[45-52], also plays a significant role in many liquid manipulating systems. For example, a local radius reduced to the microscale, can result in an extremely partial curling of the liquid meniscus, leading to ultrahigh curvature and a remarkable pressure difference, which contributes to high-speed liquid spreading of up to several centimeters per second. The capillary rise, h, can be derived from the Lucas-Washburn equation[53]:

where ρ is the liquid density, g is the gravity acceleration, η is the liquid viscosity, r is the capillary radius,

In addition to the geometrical gradients and capillary rise, gradients of surface energy, which is stemmed from the difference in surface chemistry[54,55] or micro/nano structures[56,57], can also enhance liquid manipulating interfaces[38,58]. When a droplet comes into contact with surfaces featured by high surface energy, compared to the liquid surface tension statistically, (in other words, hydrophilic or superhydrophilic surfaces), it usually spreads to form liquid films with relatively smaller contact angles. On the contrary, a higher contact angle can be observed if droplets interact with surfaces which possess lower surface energy (hydrophobic/superhydrophobic surfaces). Regulating such differences in surface energy also initiates the motion of liquids and bulk droplets by the driving force:

where l is the integration variable of local distance, θA and θB are the local contact angles.

The aforementioned approaches present the usually applied fundamental models of liquid manipulating interfaces. These mechanisms rarely occur solely in a practical system, but may play different roles in various scenarios.

3. Features and Designments

Despite the standing 3D space of all the structures and devices, the mobility of liquids can vary a lot to each other. Understanding these various mobilities can be helpful in providing guidance and convenience for practical conditions. In this paper, we consider liquid manipulating interfaces in three basic forms. Structures that allow only forward or backward spreading are regarded as 1D fiber-like channels. Interfaces that enable transport and turning within a plane are regarded as 2D substrates. Those interfaces that steer and transport along stereoscopic paths are regarded as 3D architectures, as Figure 3 depicts.

3.1 1D fiber-like channels

Fiber or fiber-like structures, such as ideal cylinders and animal hair in Figure 3a, possess 1D liquid channels for the advancing or retreating of liquids[59-64]. For example, spider silk was found to initiate droplet aggregation. The wet swelling property of such silk can enhance its partial geometric differences between spindle-knots and joints, resulting in a considerable Laplace pressure difference. Besides, the micro/nano structures on silk also generate typical surface energy gradients, which promote the self-transport of captured droplets from joint areas toward spindle-knots. Different from spider silk, some recently reported papers proposed attractive methods to handle droplets in 1D channels. For instance, the surface tension-dependent different spreading modes on Araucaria Leaf-like structures[65]. Researchers deepened their understanding of how inherent liquid surface tension can influence their macro movements in the same environment. In one recently published paper, researchers prepared a multi-bioinspired capillary cantilever structure[66] by UV-curing to acquire noticeable improvements in antigravity capillary climbing. The tilted eight-layer overhang structure, combined with a capillary corridor, achieved a high antigravity pick up distance of ~107 mm of pure water, a value approaching the theoretical limit. This structure simultaneously demonstrates desirable unidirectional self-transport capacity, which was confirmed to benefit diverse applications like signal testing and position predicting, etc. To endow more charming flexibility and functionality to liquid behavior, a periodic reentrant fiber-like structure[67] was proposed recently, composed of many one-way hemline-shaped units connected end to end. The unique sectional pattern provided a considerable capillary difference, showing the unidirectional self-transport of liquids. Moreover, the basic material property can allow this fiber-like structure to be buckled as needed, presenting some flexibility and on-site maneuverability. Undeniably, when assembled line by line or via other strategies, such 1D fiber or fiber-like channels can of course construct more complicated or functional patterns beyond simple one-dimensional mobility, but considering the confined droplet movement modes, namely only forward or backward, they are still categorized as 1D fiber-like channels

3.2 2D on-surface droplet transport

Different from the above discussed 1D liquid channels, various works have focused on regulating liquids on 2D substrates[68-70], where diverse motion modes like steering, mixing and distribution can occur[71]. As a typical planar substrate, Chinese origami is becoming more and more popular because of the abundant asymmetrical characteristics. Researchers transformed superhydrophilic aluminum sheets to an asymmetric shell-like structure by a Chinese origami scheme[72], to achieve high efficiency steam collecting and directional liquid delivery. The shell-like structure allows the captured droplets, from any position or direction on the origami, to be transported from the wider outside to the narrower inside and then get enriched. Specifically, this origami structure can be regarded as the integration of multiple 1D asymmetrical channels for 2D amplified performance, like flow capacity as well as transport efficiency. Meanwhile, generating wettability patterns has also been proved practicable. Constructing surfaces with gradients of superwettability[73-75], for example, superhydrophilic inner liquid channels and a superhydrophobic external background, can finally generate periodic Janus wettability boundaries[76], achieving a remarkable normalized transport distance up to 23.7 for a ~3 μL droplet, attributed to the fine Janus wettability and the designed periodic convergent channel. Moreover, by cutting such continuous channels into modular units, researchers have proved unidirectional transport capacity, programmability, and on-site reconfigurability on such 2D substrates[77]. To further promote the path-regulating capacity, researchers take advantage of flexible polymer materials to construct an open channel with an asymmetrical capillary track[78]. The inherent flexibility endows the liquid track with different geometrical gradients. Local curvatures of the liquid meniscus can lead to a Laplace pressure difference, which promotes versatility of droplet transport. Different from sealed microfluidics, such open channels were confirmed to allow efficient mass transfer at the liquid-gas interfaces, like gas generation and release, and air filtration with particle absorption, finding benefits in portable devices.

3.3 3D stereoscopic spreading

Nature provides many prototypes of 3D structures on a microscale, accelerating the multiphase transport and reaction processes. To meet the needs of Green and sustainable Development Strategy, and the target of carbon neutrality, researchers have long been devoted to exploring higher efficiency mass transfer devices by mimicking nature. Drawn inspirations from the natural vessel of tree plants, cellular fluidic devices[79] were constructed by large-area projection micro stereolithography printers. By handling the density of the surrounding units, the capillary force within the units can be adjusted, and thus drive the movements of droplets in this device, realizing directional, unidirectional and even programmable self-transport of liquids. Benefiting from the dense cellular units, the spreading liquid is endowed with considerable liquid-gas interfaces, demonstrating profits to the gas-liquid transport processes such as absorption of carbon dioxide and multiphase process engineering. The large two-phase contact surfaces of such cellular devices have attracted wide attention from researchers worldwide. By designing one bar or two nonparallel bars between two adjacent connected polyhedral frame units[80], the liquid capturing modes can be changed on demand, from a preserving mode of the one-bar frame to releasing mode of the two-bar frame. Such differences allow switching between liquid capture and release locally, dynamically and reversibly, enabling control over concentrations of multiple materials, packaging of liquid arrays, etc. The studies further demonstrate the controllability of liquids by regulating local connecting modes to further facilitate the manipulation of direction, velocity, and path of the flow[81].

As summarized in Figure 3b, it is interesting that most of the mentioned works confirmed a relatively higher flow rate for 3D structures compared to that of 2D ones, which are also higher than 1D structures, under similar channel sizes. Besides, possible potentials are under-explored in some blank of this phase map, for example, micro/nano devices with dramatically small yet significant flow, or macro devices with more competitive flow than traditional strategies. Despite the observable progress, some works rarely transfer their bare structures to functional devices because of insufficient cost efficiency, feasibility of mass production, and, most importantly, precise orientation in specific application scenarios. Thus, summarizing potential application fields is of great importance for further studies, especially taking into account current challenges and requirements from both research and industry.

4. Emerging Applications

Regulating the formation and variation of liquids plays a significant part in steering bulk droplets, liquid films, dissolved contents, and even surface charge. As depicted in Figure 4, we studied the state-of-the-art works and summarized 10 features which shall point out the way toward further design for not only scientific research but also practical engineering. It is worth noting that not all related features are included in this map for the conciseness of the paper. Future developments may witness more and more characteristics for better guidance.

4.1 Water harvesting

To handle the challenge of worldwide pure water scarcity, harvesting water from the atmosphere is regarded as promising and has been proved applicable in more and more recent advancements[82-85]. Inspired by some natural creatures that survive in harsh rigid environments, such as the desert beetle and cactus thorn, current water harvesting devices usually make use of the considerable solid-liquid-gas interfaces provided by 1D or 2D channels[86]. For example, by assembling cylindrical fibers into crisscross nets[87], the flux of mist going through the net is increased significantly, and the lateral flow is restricted as needed. Simultaneously, the well-organized fiber nets also provide a considerable contact area to increase water harvesting efficiency. Notably, the condensed water droplets on such cylindrical fiber net are only collected when their corresponding sizes increase to be dragged down by gravity. However, generating spider-silk like fibers and constructing bioinspired networks can allow the condensed droplets to aggregate more efficiently. By mimicking natural spider silk, researchers generated biomimetic spindle knots and joints on stretchable fibers using gas-in-water jet templates[88]. The geometrical gradients of this fiber endow the self-transport of condensed droplets from joints to spindle knots, refreshing the liquid-gas interfaces more frequently and accelerating the droplet growth meanwhile. Besides the mentioned methods above, which are based on 1D fibers, 2D functional devices designed for high-efficiency water harvesting is also explored. Researchers proposed a harp-like fog collector[89] with superhydrophobicity and confirmed a enhanced water harvesting efficiency of 57% higher than pure superhydrophilic surface. Both the quick refreshing of surfaces and the enhanced flow rate are proved to contribute key roles in this process.

4.2 Power generation

The variations of liquid-gas interfaces also result in ion migration, which subsequently contributes to local potential differences[90]. By employing such phenomena to a proper circuit loop, the droplet induced voltage can be recorded and used, being considered a typical tribo-electric nano-generator (TENG). The current sparking potential of droplet-induced TENG has even reached 1,200 V[91], approaching the theoretical upper limit. Researchers have confirmed the key roles of high sliding speed and large contact area of the impacting droplet, as well as the circuit capacitance at the contact instant, in achieving ultrahigh sparking potential. By optimizing these two parameters, the achieved ultrahigh sparking potentials can even stimulate the ionization of helium gas directly at the atmospheric pressure. So, how to regulate the liquid movement efficiently in such TENG devices? Controlling surface wettability may be a possible candidate, for example, applying Janus wettability on porous polytetrafluoroethylene films[92]. Leveraging hierarchically porous polyaniline and polydopamine modified carbon nanotubes nanofilaments on a commercial PVDF substrate, water-energy cogeneration was realized, simultaneously providing a durable power density of 2.78 μW cm-2 and enhanced pure water production. Similarly, by constructing appropriate interfacial architectures with desirable wettability, for instance, hydrophobic fluorinated groups[93], charge accumulation and transfer can be promoted to satisfy the driving of reactive oxygen species generation at the solid-liquid-air interfaces, thereby markedly enhancing the disinfection rate in water treatments. This portable device confirmed an inactivation rate to 99.9999% of Vibrio cholerae within 1 min of hand powered operation.

4.3 Interfacial evaporation and cooling

Seawater, despite its high salt content, is widely recognized as a promising resource for freshwater scarcity and a huge salt storage. Among common seawater utilization methods, interfacial evaporation is catching more and more attention for transferring brine from the ocean to freshwater and facilitating salt precipitation[94-99]. Researchers embedded the pollutant capture property of polyvinyl alcohol-phytic acid and its hierarchical macro-micro porous architecture, that enables efficient liquid uptake capacity[100]. Combining this multifunctionality with a carbon fiber matrix, which served as a phase change base material for thermal storage, they achieved highly efficient interfacial evaporation, clean salt production, and simultaneous generation of authigenic electricity. As confirmed, porous materials, with high porosity and interconnected microchannels inside, contribute to considerable higher capillary effects, stronger liquid uptake capacity, and hierarchical multi-phase contacting areas, so as to find wide application potential in interfacial evaporation scenarios. The state-of the-art-works further inserted responsive capability into porous evaporators to guide needed multi-phase contacting areas[101]. The porous polydopamine layer was used to provide photothermal functionality and microchannels for efficient water uptake. Meanwhile, to control the thickness of the water film to a desirable and optimized level, a thermo-responsive sporopollenin layer was applied under the polydopamine layer as a switchable water gate. Such a water gate was confirmed to enhance evaporation rate by minimizing latent heat at high temperatures. Interestingly, meeting the dramatically growing requirements on heat dissipation of high-performance computing chips, especially with the development and application of artificial intelligence, evaporation-induced cooling methods also seem to be a promising candidate for its highly efficient phase change capability[102]. Some researchers developed various types of capillary structures, like classical Tesla valves[17], into heating chips and proved their practicality in thermal regulation. Such capillary structures were shown to eliminate possible vapor backflow and simultaneously promote liquid flow rate along the sidewalls of heating chips, which synergistically enable the thermal regulation to self-adapt to varying working conditions.

4.4 Liquid-liquid separation

Distinct interface tensions between liquid and solid enable different solid-liquid-air behaviors, which further facilitate phase separation in petrochemical process and environmental protection[103,104]. Previously, a multi-bioinspired conical spine with dual micro grooves enabled spontaneous oil-water separation and even dragged oil droplets across the air-water interface[105]. The designed cone structure was enlightened by the geometrical gradient of fishbones and the microgrooves of rice leaves, featuring vertical and horizontal microgrooves which provide enhanced capillary effect. The transport velocity and separation efficiency were both enhanced for under water oil extraction. More conveniently, by assembling two commercially available steel sticks at one end and carving hierarchical microchannels by laser[106], can achieve oil-water separation with a surface tension difference as low as 0.87 mN·m-1. Besides, dual-bionic gears were recently proposed to separate oil-in-water emulsions[107]. The designed gears were generated with superwettability and complementary topological structures, which allowed water and oil droplets to continuously spread on wettability-preferential surfaces. With the help of the rotational motion of the complementary gears, the separation flux was significantly improved. The above works make good use of superwettability to realize phase separation. Furthermore, regulating partial interfaces by constructing subtle wettability patterns, in other words, membranes with Janus channels, can even enable the separation and recovery of surfactant-stabilized emulsions[108]. Such membranes allow preferential penetration of micro-scale oil and water droplets, and if assembled with a feedback loop that involves enrichment and demulsification, 99.7 % purity can be achieved finally.

4.5 Wearable electronics

Monitoring human dynamic indicators by wearable electronics provides portable, wireless, and real-time feedback, while inevitably encountering sweat immersion that may arise signal uncertainty. Therefore, wicking sweat away from electronics by steering liquids through Janus channels or gradient textiles is believed to ensure reliable working and comfortable sensing[109]. So, how to steer moisture efficiently? A recently proposed integrated permeable electronic system was designed with a 3D liquid diode featuring spatially heterogeneous wettability between multiple interlayers[15]. Through poles were uniformly distributed in the designed wettable interlayer, which allows for the self-pumping of sweat flows from the bottom skin to the uppermost device surface unidirectionally with a flow rate of 11.6 mL·cm-2·min-1, which is 4,000 times greater than the natural sweat rate during daily exercises. But how to provide reliable power supply for such wireless and soft electronics without sacrificing comfort and portable properties? Seeking help from triboelectric nanogenerators may be promising, in other words, self-powered monitoring systems[110]. By integrating a sweat-activated battery as a built-in power source, wearable electronics can simultaneously realize sweat extraction, microfluidics with biosensors, and even near field communication for data processing and collection. Specifically, attaining energy from external environments spontaneously, for example, solar energy, is also a potential solution, too. Very recently, a wearable solar fluidic system was proposed to combine freshwater production, energy supply, and information exchange[111]. This system was based on a photothermal fabric which generates a temperature gradient for efficient transport of sodium ions, resulting in 8.50 volts of power. Besides, the photothermal effect contributes to the interfacial evaporation of moisture collected from human skin and generates freshwater of 24.2 liters per kilogram of this fabric.

4.6 Modern healthcare and dressings

Medical conduits, implantable materials, and wound-contacting dressings are of great significance for treating a wide range of clinical conditions, while inevitably encountering inflammation problems and secretory liquids[112,113]. Guiding such pus and liquids away from the wound area timely, by liquid manipulating interfaces, may eliminate possible infections[114] and benefit wound recovery[20]. Previously, researchers proposed a single sub-capillary-length-scale device as smart tympanostomy tubes[115]. Applying an iterative screening algorithm, they generated unique curved lumen geometries on conventional engineered tubes. Such geometrical gradients thus create enough difference on liquid-air interfaces so as to facilitate simultaneous drug delivery, effusion drainage, water resistance, and biocontamination/ingrowth prevention on only one single device. This design nearly eliminates the adhesion and growth of common pathogenic bacteria, blood, and cells, providing a novel form of modern healthcare devices. If we consider such functional tubes as 1D fiber-like liquid channels, some dressings can provide 2D on-surface liquid spreading. For instance, a self-pumping organohydrogel dressing was proposed with hydrophilic fractal microchannels which rapidly drain excessive exudates with 30 times enhancement in efficiency compared to pure hydrogel, benefiting potential burn wounds[116]. Using a creaming-assistant emulsion interfacial polymerization approach, researchers constructed abundant microchannels between the fractal hydrogel network and organogel particles to the whole dressing surface. Postoperative adhesion demands robust wet-tissue management under complicated liquid-solid, liquid-air, and even liquid-liquid interfacial conditions. By controlling the interfacial distribution of free carboxyl groups through steering stirring speed, an integrally formed Janus hydrogel can be fabricated in one step[19]. Bulk droplets with relatively bigger sizes containing emulsions occupy the top hydrogel surface and hinder the exposure of carboxyl groups on the top surface, driving them to be more distributed on the bottom surface. Such centrifugal-force-induced differences in liquid distribution can finally result in poor adhesion of top surface but robust adhesion of bottom surface to various wet tissues, even underwater, contributing to efficient wound repair with no impact to surrounding organs.

5. Conclusions and Outlook

Learning from nature has long been proved practicable in addressing challenges in human research and engineering. Up to now, a wealth of works has been dedicated to explaining natural phenomena, replicating typical functions, constructing fundamental models, and guiding manufacturing. These studies unveiled vast useful tools, like wettability or super-wettability, surface roughness, micro/nano structures, and macro/micro geometrical gradients, to name a few, which, solely or synergistically generate the needed curling liquid meniscus to accomplish diverse mobility of bulk droplets or included contents. Attributed to the progress so far, various application potentials are confirmed, and we then benefit from these optimized liquid manipulating interfaces. Current developments are pleasing, with an increasing number of bioinspired advanced structures are applied to functional devices, characterizing advantages like portability, wearability, flexibility, and more comfort. However, gaps persist between bioinspired structures and practical functional devices. Addressing these gaps calls for joint efforts from multiple disciplines, including but not limited to mechanics, materials, chemistry, physics, and of course the further development of modern manufacturing methods, like laser writing, 3D printing, micro/nano self-assembling, and so on.

The development of liquid manipulating interfaces inevitably proceeds to higher efficiency, better compact designs, more desirable robustness, and easier mass production to facilitate further applications. It should be noted that not all natural phenomena and possible applications are summarized in this paper due to space limitations and their rapid updates, for example, 3D printing[117,118], soft robotics and smart sensing[119-121], cell culturing[122], anti/de-icing[123,124], interfacial self-assembling[125,126], etc. Besides, although not discussed in this paper, the combination of possible external energy inputs, like acoustic stimuli[127-130], light illumination[131-133], thermal gradient[134-136], electric[137,138] and magnetic fields[139,140] for regulating liquid behavior, is also widely explored and applied. As we anticipate, liquid manipulating interfaces should meet numerous requirements in designing smart devices, and we envision that this review can inspire more breakthroughs and innovative ideas for readers and relative communities in fields like microfluidics, chemical engineering, advanced devices, etc.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the utilization of image generation tool, yiyan.baidu.com, for the schematics of nepenthes alata and spider silk in Figure 1.

Authors contribution

Cao M: Conceptualization, supervision, writing-review & editing.

Li G: Conceptualization, supervision.

Liu J: Writing-original draft.

Bai H: Writing-review & editing.

All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key R & D Program of China (2022YFA1504002), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52522312, 52373247).

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

References

-

1. Prakash M, Quéré D, Bush JW. Surface tension transport of prey by feeding shorebirds: The capillary ratchet. Science. 2008;320(5878):931-934.[DOI]

-

2. Yang L, Li W, Lian J, Zhu H, Deng Q, Zhang Y, et al. Selective directional liquid transport on shoot surfaces of Crassula muscosa. Science. 2024;384(6702):1344-1349.[DOI]

-

3. Comanns P, Buchberger G, Buchsbaum A, Baumgartner R, Kogler A, Bauer S, et al. Directional, passive liquid transport: The Texas horned lizard as a model for a biomimetic ‘liquid diode’. J R Soc Interface. 2015;12(109):20150415.[DOI]

-

4. Bai H, Zhao T, Cao M. Interfacial fluid manipulation with bioinspired strategies: Special wettability and asymmetric structures. Chem Soc Rev. 2025;54(4):1733-1784.[DOI]

-

5. Xuan S, Zhuo L, Li G, Zeng Q, Liu J, Yu J, et al. Micro/nano hierarchical crater-like structure surface with mechanical durability and low-adhesion for anti-icing/deicing. Small. 2024;20(43):e2404979.[DOI]

-

6. Zhang Y, Huang Z, Cai Z, Ye Y, Li Z, Qin F, et al. Magnetic-actuated “capillary container” for versatile three-dimensional fluid interface manipulation. Sci Adv. 2021;7(34):eabi7498.[DOI]

-

7. Dai H, Dong Z, Jiang L. Directional liquid dynamics of interfaces with superwettability. Sci Adv. 2020;6(37):eabb5528.[DOI]

-

8. Farber EM, Seraphim NM, Tamakuwala K, Stein A, Rücker M, Eisenberg D. Porous materials: The next frontier in energy technologies. Science. 2025;390(6772):eadn9391.[DOI]

-

9. Song J, Chen Y. Self-propelled hydrogels that glide on water. Sci Robot. 2021;6(53):eabh1399.[DOI]

-

10. Alipanahrostami M, McCoy TR, Li M, Wang W. Surfactant-mediated mobile droplets on smooth hydrophilic surfaces. Droplet. 2025;4(2):e70004.[DOI]

-

11. Sinha Mahapatra P, Ganguly R, Ghosh A, Chatterjee S, Lowrey S, Sommers AD, et al. Patterning wettability for open-surface fluidic manipulation: Fundamentals and applications. Chem Rev. 2022;122(22):16752-16801.[DOI]

-

12. Li Y, Shi Z, Xu B, Jiang L, Liu H. Bioinspired Plateau-Rayleigh instability on fibers: From droplets manipulation to continuous liquid films. Adv Funct Mater. 2024;34(32):2316017.[DOI]

-

13. Di Novo NG, Bagolini A, Pugno NM. Single condensation droplet self-ejection from divergent structures with uniform wettability. ACS Nano. 2024;18(12):8626-8640.[DOI]

-

14. Zhu T, Ni Y, Zhao K, Huang J, Cheng Y, Ge M, et al. A breathable knitted fabric-based smart system with enhanced superhydrophobicity for drowning alarming. ACS Nano. 2022;16(11):18018-18026.[DOI]

-

15. Zhang B, Li J, Zhou J, Chow L, Zhao G, Huang Y, et al. A three-dimensional liquid diode for soft, integrated permeable electronics. Nature. 2024;628(8006):84-92.[DOI]

-

16. Dai Y, Nolan J, Madsen E, Fratus M, Lee J, Zhang J, et al. Wearable sensor patch with hydrogel microneedles for in situ analysis of interstitial fluid. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2023;15(49):56760-56773.[DOI]

-

17. Li W, Yang S, Chen Y, Li C, Wang Z. Tesla valves and capillary structures-activated thermal regulator. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):3996.[DOI]

-

18. Wu Z, Xiao W, He H, Wang W, Song B. Jet-enhanced manifold microchannels for cooling electronics up to a heat flux of 3,000 W cm-2. Nat Electron. 2025;8(9):810-817.[DOI]

-

19. Wang H, Yi X, Liu T, Liu J, Wu Q, Ding Y, et al. An integrally formed janus hydrogel for robust wet-tissue adhesive and anti-postoperative adhesion. Adv Mater. 2023;35(23):e2300394.[DOI]

-

20. Guo J, Yu Y, Shen Y, Sun X, Bi Y, Zhao Y. Multiple bio-actives loaded gellan gum microfibers from microfluidics for wound healing. Small. 2023;19(44):e2303887.[DOI]

-

21. Miao D, Huang Z, Wang X, Yu J, Ding B. Continuous, spontaneous, and directional water transport in the trilayered fibrous membranes for functional moisture wicking textiles. Small. 2018;14(32):e1801527.[DOI]

-

22. Pornrungroj C, Mohamad Annuar AB, Wang Q, Rahaman M, Bhattacharjee S, Andrei V, et al. Hybrid photothermal–photocatalyst sheets for solar-driven overall water splitting coupled to water purification. Nat Water. 2023;1(11):952-960.[DOI]

-

23. Song Y, Zeng M, Wang X, Shi P, Fei M, Zhu J. Hierarchical engineering of sorption-based atmospheric water harvesters. Adv Mater. 2024;36(12):e2209134.[DOI]

-

24. Yu Z, Zhu T, Zhang J, Ge M, Fu S, Lai Y. Fog harvesting devices inspired from single to multiple creatures: Current progress and future perspective. Adv Funct Mater. 2022;32(26):2200359.[DOI]

-

25. Lee Y, Fan S, Yang S. Nature-inspired design strategies for efficient atmospheric water harvesting. Adv Mater. 2025.[DOI]

-

26. Wang Q, Sheng Y, Song X, Qiu Y, Li X, Shang C, et al. Functional liquid layer enables superior performance of air purification filter. Chem. 2025;11:102526.[DOI]

-

27. Zheng Y, Bai H, Huang Z, Tian X, Nie FQ, Zhao Y, et al. Directional water collection on wetted spider silk. Nature. 2010;463(7281):640-643.[DOI]

-

28. Ju J, Bai H, Zheng Y, Zhao T, Fang R, Jiang L. A multi-structural and multi-functional integrated fog collection system in cactus. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1247.[DOI]

-

29. Barthlott W, Neinhuis C. Purity of the sacred lotus, or escape from contamination in biological surfaces. Planta. 1997;202(1):1-8.[DOI]

-

30. Chen H, Zhang P, Zhang L, Liu H, Jiang Y, Zhang D, et al. Continuous directional water transport on the peristome surface of Nepenthes alata. Nature. 2016;532(7597):85-89.[DOI]

-

31. Lu Y, Sathasivam S, Song J, Crick CR, Carmalt CJ, Parkin IP. Robust self-cleaning surfaces that function when exposed to either air or oil. Science. 2015;347(6226):1132-1135.[DOI]

-

32. Xue L, Li A, Li H, Yu X, Li K, Yuan R, et al. Droplet-based mechanical transducers modulated by the symmetry of wettability patterns. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):4225.[DOI]

-

33. Nan L, Zhang H, Weitz DA, Shum HC. Development and future of droplet microfluidics. Lab Chip. 2024;24(5):1135-1153.[DOI]

-

34. He Y, Xu W, Yan K, Zhao L, Wang J, Li K, et al. Liquid directional transport surface applied to the spacecraft fluid management system: Fundamentals and prospect analysis. Droplet. 2025;4(2):e165.[DOI]

-

35. Shang L, Cheng Y, Zhao Y. Emerging droplet microfluidics. Chem Rev. 2017;117(12):7964-8040.[DOI]

-

36. Zhou M, Zhang L, Zhong L, Chen M, Zhu L, Zhang T, et al. Robust photothermal icephobic surface with mechanical durability of multi-bioinspired structures. Adv Mater. 2024;36(3):e2305322.[DOI]

-

37. Liu S, Zhang C, Shen T, Zhan Z, Peng J, Yu C, et al. Efficient agricultural drip irrigation inspired by fig leaf morphology. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):5934.[DOI]

-

38. Parker AR, Lawrence CR. Water capture by a desert beetle. Nature. 2001;414(6859):33-34.[DOI]

-

39. Zheng Y, Gao X, Jiang L. Directional adhesion of superhydrophobic butterfly wings. Soft Matter. 2007;3(2):178-182.[DOI]

-

40. Li C, Wu L, Yu C, Dong Z, Jiang L. Peristome-mimetic curved surface for spontaneous and directional separation of micro water-in-oil drops. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56(44):13623-13628.[DOI]

-

41. Cassie ABD, Baxter S. Wettability of porous surfaces. Trans Faraday Soc. 1944;40(0):546-551.[DOI]

-

42. Feng S, Delannoy J, Malod A, Zheng H, Quéré D, Wang Z. Tip-induced flipping of droplets on Janus pillars: From local reconfiguration to global transport. Sci Adv. 2020;6(28):eabb4540.[DOI]

-

43. Zhang Y, Li L, Li G, Lin Z, Wang R, Chen D, et al. Topological elastic liquid diode. Sci Adv. 2025;11(14):eadt9526.[DOI]

-

44. Yamagishi K, Ching T, Chian N, Tan M, Zhou W, Huang SY, et al. Flexible and stretchable liquid-metal microfluidic electronics using directly printed 3D microchannel networks. Adv Funct Mater. 2024;34(31):2311219.[DOI]

-

45. Yafia M, Ymbern O, Olanrewaju AO, Parandakh A, Sohrabi Kashani A, Renault J, et al. Microfluidic chain reaction of structurally programmed capillary flow events. Nature. 2022;605(7910):464-469.[DOI]

-

46. Gopinathan KA, Mishra A, Mutlu BR, Edd JF, Toner M. A microfluidic transistor for automatic control of liquids. Nature. 2023;622(7984):735-741.[DOI]

-

47. Ouali FF, McHale G, Javed H, Trabi C, Shirtcliffe NJ, Newton MI. Wetting considerations in capillary rise and imbibition in closed square tubes and open rectangular cross-section channels. Microfluid Nanofluid. 2013;15(3):309-326.[DOI]

-

48. Rye RR, Mann JA, Yost FG. The flow of liquids in surface grooves. Langmuir. 1996;12(2):555-565.[DOI]

-

49. Kolliopoulos P, Jochem KS, Lade Jr RK, Francis LF, Kumar S. Capillary flow with evaporation in open rectangular microchannels. Langmuir. 2019;35(24):8131-8143.[DOI]

-

50. Romero LA, Yost FG. Flow in an open channel capillary. J Fluid Mech. 1996;322:109-129.[DOI]

-

51. Li J, Zheng H, Zhou X, Zhang C, Liu M, Wang Z. Flexible topological liquid diode catheter. Mater Today Phys. 2020;12:100170.[DOI]

-

52. Chen F, Cheng Z, Gao C, Li C, Zhang C, Yu C, et al. Capillarity constructed open siphon for sustainable drainage. Small. 2024;20(36):e2307079.[DOI]

-

53. Szekely J, Neumann AW, Chuang YK. The rate of capillary penetration and the applicability of the washburn equation. J Colloid Interface Sci. 1971;35(2):273-278.[DOI]

-

54. Wu J, Hwang YH, Yadavali S, Lee D, Issadore DA. Micro-patterning wettability in very large scale microfluidic integrated chips for double emulsion generation. Adv Funct Mater. 2024;34(3):2309718.[DOI]

-

55. Chen Y, Liu Z, Liu K, Huang Y, Wang Z. Surface microstructure and activity of nanoporous W-based materials via anodization and deoxidization. Surf Sci Technol. 2025;3(1):7.[DOI]

-

56. Malvadkar NA, Hancock MJ, Sekeroglu K, Dressick WJ, Demirel MC. An engineered anisotropic nanofilm with unidirectional wetting properties. Nat Mater. 2010;9(12):1023-1028.[DOI]

-

57. Chen F, Wang Y, Tian Y, Zhang D, Song J, Crick CR, et al. Robust and durable liquid-repellent surfaces. Chem Soc Rev. 2022;51(20):8476-8583.[DOI]

-

58. Chaudhury MK, Whitesides GM. How to make water run uphill. Science. 1992;256(5063):1539-1541.[DOI]

-

59. Wilson JL, Pahlavan AA, Erinin MA, Duprat C, Deike L, Stone HA. Aerodynamic interactions of drops on parallel fibres. Nat Phys. 2023;19(11):1667-1672.[DOI]

-

60. Chen H, Ran T, Gan Y, Zhou J, Zhang Y, Zhang L, et al. Ultrafast water harvesting and transport in hierarchical microchannels. Nat Mater. 2018;17(10):935-942.[DOI]

-

61. Ju J, Zheng Y, Jiang L. Bioinspired one-dimensional materials for directional liquid transport. Acc Chem Res. 2014;47(8):2342-2352.[DOI]

-

62. Ma X, Cao M, Teng C, Li H, Xiao J, Liu K, et al. Bio-inspired humidity responsive switch for directional water droplet delivery. J Mater Chem A. 2015;3(30):15540-15545.[DOI]

-

63. Lee M, Oh J, Lim H, Lee J. Enhanced liquid transport on a highly scalable, cost-effective, and flexible 3D topological liquid capillary diode. Adv Funct Mater. 2021;31(21):2011288.[DOI]

-

64. Bintein PB, Bense H, Clanet C, Quéré D. Self-propelling droplets on fibres subject to a crosswind. Nat Phys. 2019;15(10):1027-1032.[DOI]

-

65. Feng S, Zhu P, Zheng H, Zhan H, Chen C, Li J, et al. Three-dimensional capillary ratchet-induced liquid directional steering. Science. 2021;373(6561):1344-1348.[DOI]

-

66. Liu X, Gao M, Li B, Liu R, Chong Z, Gu Z, et al. Bioinspired capillary transistors. Adv Mater. 2024;36(41):e2310797.[DOI]

-

67. Yang C, Yu Y, Shang L, Zhao Y. Flexible hemline-shaped microfibers for liquid transport. Nat Chem Eng. 2024;1(1):87-96.[DOI]

-

68. Zhao Z, Li W, Hu X, Deng Q, Zhang Y, Jiang S, et al. The limit of droplet rebound angle. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):5684.[DOI]

-

69. Pelizzari M, McHale G, Armstrong S, Zhao H, Ledesma-Aguilar R, Wells GG, et al. Droplet self-propulsion on slippery liquid-infused surfaces with dual-lubricant wedge-shaped wettability patterns. Langmuir. 2023;39(44):15676-15689.[DOI]

-

70. Yin K, Wang L, Deng Q, Huang Q, Jiang J, Li G, et al. Femtosecond laser thermal accumulation-triggered micro-/nanostructures with patternable and controllable wettability towards liquid manipulating. Nanomicro Lett. 2022;14(1):97.[DOI]

-

71. Li Z, Xu M, Li M, Bai H, Wang X, Zhao T, et al. Erasable and programmable unidirectional liquid transport on multiple asymmetric slippery microstructures. ACS Nano. 2025;19(21):19854-19865.[DOI]

-

72. Bai H, Wang X, Li Z, Wen H, Yang Y, Li M, et al. Improved liquid collection on a dual-asymmetric superhydrophilic origami. Adv Mater. 2023;35(17):e2211596.[DOI]

-

73. Han K, Wang Z, Han X, Wang X, Guo P, Che P, et al. Active manipulation of functional droplets on slippery surface. Adv Funct Mater. 2022;32(45):2207738.[DOI]

-

74. Chu F, Ni Z, Wen D, Feng Y, Li S, Jiang L, et al. Liquid film sculpture via droplet impacting on microstructured heterowettable surfaces. Adv Funct Mater. 2022;32(26):2203222.[DOI]

-

75. Zhang Q, Bai X, Li Y, Zhang X, Tian D, Jiang L. Ultrastable super-hydrophobic surface with an ordered scaly structure for decompression and guiding liquid manipulation. ACS Nano. 2022;16(10):16843-16852.[DOI]

-

76. Xie D, Zhang BY, Wang G, Sun Y, Wu C, Ding G. High-performance directional water transport using a two-dimensional periodic janus gradient structure. Small Methods. 2022;6(12):e2200812.[DOI]

-

77. Liu J, Zhao C, Bai H, Li G, Li H, Wang Y, et al. Programmable and unidirectional liquid self-transport on modular fluidic units. Adv Mater. 2025;37(47):e08530.[DOI]

-

78. Cao M, Qiu Y, Bai H, Wang X, Li Z, Zhao T, et al. Universal liquid self-transport beneath a flexible superhydrophilic track. Matter. 2024;7(9):3053-3068.[DOI]

-

79. Dudukovic NA, Fong EJ, Gemeda HB, DeOtte JR, Cerón MR, Moran BD, et al. Cellular fluidics. Nature. 2021;595(7865):58-65.[DOI]

-

80. Zhang Y, Huang Z, Qin F, Wang H, Cui K, Guo K, et al. Connected three-dimensional polyhedral frames for programmable liquid processing. Nat Chem Eng. 2024;1(7):472-482.[DOI]

-

81. Wu S, Sun S, Ye J, Wang L, Zhang Y. Capillary-driven 3D open fluidic networks for versatile continuous flow manipulation. Adv Mater. 2025;37(44):e2503840.[DOI]

-

82. Li C, Yu C, Zhou S, Dong Z, Jiang L. Liquid harvesting and transport on multiscaled curvatures. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117(38):23436-23442.[DOI]

-

83. Cui Z, Zhang Y, Zhang Z, Liu B, Chen Y, Wu H, et al. Durable janus membrane with on-demand mode switching fabricated by femtosecond laser. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):1443.[DOI]

-

84. Shao Z, Wang ZS, Lv H, Tang YC, Wang H, Du S, et al. Modular all-day continuous thermal-driven atmospheric water harvester with rotating adsorption strategy. Appl Phys Rev. 2023;10(4):41409.[DOI]

-

85. Wei H, Qin B, Luo H, Zhou X, Wang X, Mei Y. Efficient fog harvesting system inspired by cactus spine and spider silk with vertical crisscross spindle structure. Chem Eng J. 2025;507:160747.[DOI]

-

86. Zhang Z, Li T, Yuan Y, Zhang Z, Ling C, Yao X, et al. A self-sufficient system for fog-to-water conversion and nitrogen fertilizer production to enhance crop growth. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):4926.[DOI]

-

87. Huang Y, Chen Q, Li Y, Li X, Yu H, Tan Z. Multi-scale modeling of fog harvesting using thin-fiber grids–towards new design rubrics. Sep Purif Technol. 2025;354:129137.[DOI]

-

88. Tian Y, Zhu P, Tang X, Zhou C, Wang J, Kong T, et al. Large-scale water collection of bioinspired cavity-microfibers. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):1080.[DOI]

-

89. Bai H, Sun H, Ye Z, Li Z, Zhao T, Wang X, et al. Unravelling the aerodynamic enhancement of water harvesting via dynamic liquid bumps. Mater Horiz. 2025;12(16):6217-6228.[DOI]

-

90. Yang C, Wang H, Bai J, He T, Cheng H, Guang T, et al. Transfer learning enhanced water-enabled electricity generation in highly oriented graphene oxide nanochannels. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):6819.[DOI]

-

91. Li L, Li X, Deng W, Shen C, Chen X, Sheng H, et al. Sparking potential over 1200 V by a falling water droplet. Sci Adv. 2023;9(46):eadi2993.[DOI]

-

92. Wang Y, Jin P, Yuan S, Zhou Z, Dai Z, Luis P, et al. Janus membrane for simultaneous water purification and power generation. Adv Funct Mater. 2025;35(31):2425757.[DOI]

-

93. Chen Z, Zhang Y, Lv P, Wu T, He J, Du J, et al. Hand-powered interfacial electric-field-enhanced water disinfection system. Nat Nanotechnol. 2025.[DOI]

-

94. Liu H, Luo H, Huang J, Chen Z, Yu Z, Lai Y. Programmable water/light dual-responsive hollow hydrogel fiber actuator for efficient desalination with anti-salt accumulation. Adv Funct Mater. 2023;33(33):2302038.[DOI]

-

95. Fellows CM, Mustakeem M, Al-Ghamdi AS, Brown TC, Ihm S. Interfacial photothermal solar desalination: A call to repentance. Desalination. 2026;617:119433.[DOI]

-

96. Tang Y, Fang C, Xu X, Li F, Fan L, Zhu D, et al. A 3D-printed hierarchical chimney for high-yield solar evaporation. Energy Environ Sci. 2025;18(17):8220-8231.[DOI]

-

97. Li J, Zhao J, Sun Y, Li Z, Murto P, Wang Z, et al. Tailor-made solar desalination and salt harvesting from diverse saline water enabled by multi-material printing. Adv Mater. 2025.[DOI]

-

98. He J, Li N, Wang S, Li S, Li J, Yu L, et al. Efficient solar-powered interfacial evaporation, water remediation, and waste conversion based on a tumbler-inspired, all-cellulose, and monolithic design. Adv Sustainable Syst. 2022;6(10):2200256.[DOI]

-

99. Liu Y, Wang C, Chen J, Lin C, Kuang W, Lian Y, et al. Diffusion-driven selective crystallization of high-purity salt through simple and sustainable one-step evaporation. Nat Water. 2025;3(8):927-936.[DOI]

-

100. Yu Z, Guo S, Zhang Y, Li W, Lu H, Tan SC. Rhus chinensis-inspired vertical hierarchical structure for solar-driven all-weather co-harvesting of fresh water, clean salts, and authigenic electricity. Adv Mater. 2025.[DOI]

-

101. Wang Y, Zhao W, Lee Y, Li Y, Wang Z, Tam KC. Thermo-adaptive interfacial solar evaporation enhanced by dynamic water gating. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):6157.[DOI]

-

102. Lo CW, Chu YC, Yen MH, Lu MC. Enhancing condensation heat transfer on three-dimensional hybrid surfaces. Joule. 2019;3(11):2806-2823.[DOI]

-

103. Wang Z, Li Y, Xie M, Zhan Z, Li W, Xie Q, et al. Biomimetic microfluidic pumps for selective oil-water separation. Adv Sci. 2025;12(27):e2503511.[DOI]

-

104. Wang D, Huang H, Min F, Li Y, Zhou W, Gao Y, et al. Antigravity autonomous superwettable pumps for spontaneous separation of oil-water emulsions. Small. 2024;20(42):e2402946.[DOI]

-

105. Li Y, Cui Z, Li G, Bai H, Dai R, Zhou Y, et al. Directional and adaptive oil self-transport on a multi-bioinspired grooved conical spine. Adv Funct Mater. 2022;32(27):2201035.[DOI]

-

106. Tang C, Zhu Y, Bai H, Li G, Liu J, Wu W, et al. Spontaneous separation of immiscible organic droplets on asymmetric wedge channels with hierarchical microchannels. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2023;15(42):49762-49773.[DOI]

-

107. Liu Z, Zhan Z, Shen T, Li N, Zhang C, Yu C, et al. Dual-bionic superwetting gears with liquid directional steering for oil-water separation. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):4128.[DOI]

-

108. Guo XY, Zhao L, Li HN, Yang HC, Wu J, Liang HQ, et al. Janus channel of membranes enables concurrent oil and water recovery from emulsions. Science. 2024;386(6722):654-659.[DOI]

-

109. Li X, Weng M, Liu T, Yu K, Zhang S, Ye Z, et al. Bioinspired heterogeneous wettability triboelectric sensors for sweat collection and monitoring. Adv Mater. 2025.[DOI]

-

110. Xu G, Huang X, Shi R, Yang Y, Wu P, Zhou J, et al. Triboelectric nanogenerator enabled sweat extraction and power activation for sweat monitoring. Adv Funct Mater. 2024;34(9):2310777.[DOI]

-

111. Meng X, Wang X, Yu B, Zhan Q, Tao Z, Liu W, et al. Wearable solar fluidic system. Sci Adv. 2025;11(44):eaea1399.[DOI]

-

112. Li S, Zhang H, Zhu M, Kuang Z, Li X, Xu F, et al. Electrochemical biosensors for whole blood analysis: Recent progress, challenges, and future perspectives. Chem Rev. 2023;123(12):7953-8039.[DOI]

-

113. Wu X, Huang D, Xu Y, Chen G, Zhao Y. Microfluidic templated stem cell spheroid microneedles for diabetic wound treatment. Adv Mater. 2023;35(28):e2301064.[DOI]

-

114. Yang Y, Zhang Y, Li G, Zhang M, Wang X, Song Y, et al. Directional rebound of compound droplets on asymmetric self-grown tilted mushroom-like micropillars for anti-bacterial and anti-icing applications. Chem Eng J. 2023;472:144949.[DOI]

-

115. Patel H, Pavlichenko I, Grinthal A, Zhang CT, Alvarenga J, Kreder MJ, et al. Design of medical tympanostomy conduits with selective fluid transport properties. Sci Transl Med. 2023;15(690):eadd9779.[DOI]

-

116. Lan J, Shi L, Xiao W, Zhang X, Wang S. A rapid self-pumping organohydrogel dressing with hydrophilic fractal microchannels to promote burn wound healing. Adv Mater. 2023;35(38):e2301765.[DOI]

-

117. Zeng C, Faaborg MW, Sherif A, Falk MJ, Hajian R, Xiao M, et al. 3D-printed machines that manipulate microscopic objects using capillary forces. Nature. 2022;611(7934):68-73.[DOI]

-

118. Lee J, Lu Y, Kashyap S, Alarmdari A, Emon MOF, Choi JW. Liquid bridge microstereolithography. Addit Manuf. 2018;21:76-83.[DOI]

-

119. Shi X, Zhu L, Yu H, Tang Z, Lu S, Yin H, et al. Interfacial click chemistry enabled strong adhesion toward ultra-durable crack-based flexible strain sensors. Adv Funct Mater. 2023;33(27):2301036.[DOI]

-

120. Li H, Yang Q, Hou J, Li Y, Li M, Song Y. Bioinspired micropatterned superhydrophilic Au-areoles for surface-enhanced raman scattering (SERS) trace detection. Adv Funct Mater. 2018;28(21):1800448.[DOI]

-

121. Zhang F, Yang M, Xu X, Liu X, Liu H, Jiang L, et al. Unperceivable motion mimicking hygroscopic geometric reshaping of pine cones. Nat Mater. 2022;21(12):1357-1365.[DOI]

-

122. Zhang Q, Toprakcioglu Z, Jayaram AK, Guo G, Wang X, Knowles TPJ. Formation of protein nanoparticles in microdroplet flow reactors. ACS Nano. 2023;17(12):11335-11344.[DOI]

-

123. Xuan S, Yin H, Li G, Zhang Z, Jiao Y, Liao Z, et al. Trifolium repens L.-like periodic micronano structured superhydrophobic surface with ultralow ice adhesion for efficient anti-icing/deicing. ACS Nano. 2023;17(21):21749-21760.[DOI]

-

124. Zhao Z, Li X, Li W, Liu M, Hu Z, Jiang T, et al. Progress in mechanism design of functional composites for anti-ice/deicing materials. Surf Sci Technol. 2024;2(1):2.[DOI]

-

125. Li A, Zhou W, Li H, Fang W, Luo Y, Li Z, et al. Drop-printing with dynamic stress release for conformal wrap of bioelectronic interfaces. Science. 2025;389(6765):1127-1132.[DOI]

-

126. Cheng M, Bai H, Wang X, Chang Z, Cao M, Bu XH. Engineering hygroscopic MOF-based silk via bioinspired interfacial assembly for fast moisture manipulation. Adv Mater. 2024;36(48):e2411680.[DOI]

-

127. Yuan Z, Lu C, Liu C, Bai X, Zhao L, Feng S, et al. Ultrasonic tweezer for multifunctional droplet manipulation. Sci Adv. 2023;9(16):eadg2352.[DOI]

-

128. Wang F, Yildiz E, Deán-Ben XL, Yu Y, Nozdriukhin D, Kang W, et al. Optoacoustic-guided magnetic microrobot platform for precision drug delivery. Adv Mater. 2025.[DOI]

-

129. Fauconnier M, Karunakaran B, Drago-González A, Wong WSY, Ras RHA, Nieminen HJ. Fast capillary waves on an underwater superhydrophobic surface. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):1568.[DOI]

-

130. Shi Z, Zhang Z, Schnermann J, Neuhauss SCF, Nama N, Wittkowski R, et al. Ultrasound-driven programmable artificial muscles. Nature. 2025;646(8087):1096-1104.[DOI]

-

131. Wang J, Gao W, Zhang H, Zou M, Chen Y, Zhao Y. Programmable wettability on photocontrolled graphene film. Sci Adv. 2018;4(9):eaat7392.[DOI]

-

132. Manabe K, Saito K, Nakano M, Ohzono T, Norikane Y. Light-driven liquid conveyors: Manipulating liquid mobility and transporting solids on demand. ACS Nano. 2022;16(10):16353-16362.[DOI]

-

133. Wang J, Song Z, He M, Qian Y, Wang D, Cui Z, et al. Light-responsive and ultrapermeable two-dimensional metal-organic framework membrane for efficient ionic energy harvesting. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):2125.[DOI]

-

134. Yang J, Li Y, Wang D, Fan Y, Ma Y, Yu F, et al. A standing Leidenfrost drop with Sufi whirling. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2023;120(32):e2305567120.[DOI]

-

135. Fan Y, Wu H, Wang J, Lv JA. Field-programmable topographic-morphing array for general-purpose lab-on-a-chip systems. Adv Mater. 2025;37(7):e2410604.[DOI]

-

136. Zhang Q, He L, Zhang X, Tian D, Jiang L. Switchable direction of liquid transport via an anisotropic microarray surface and thermal stimuli. ACS Nano. 2020;14(2):1436-1444.[DOI]

-

137. Sun Q, Wang D, Li Y, Zhang J, Ye S, Cui J, et al. Surface charge printing for programmed droplet transport. Nat Mater. 2019;18(9):936-941.[DOI]

-

138. Han X, Tan S, Jin R, Jiang L, Heng L. Noncontact charge shielding knife for liquid microfluidics. J Am Chem Soc. 2023;145(11):6420-6427.[DOI]

-

139. Wang Y, Zhang L, Du W, Zhou X, Guo Y, Zhao S, et al. Controllable bubble transport on bioinspired heteromorphic magnetically steerable microcilia. Adv Funct Mater. 2023;33(35):2302666.[DOI]

-

140. Son C, Yang Z, Kim S, Ferreira PM, Feng J, Kim S. Bidirectional droplet manipulation on magnetically actuated superhydrophobic ratchet surfaces. ACS Nano. 2023;17(23):23702-23713.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite